[ p. 65 ]

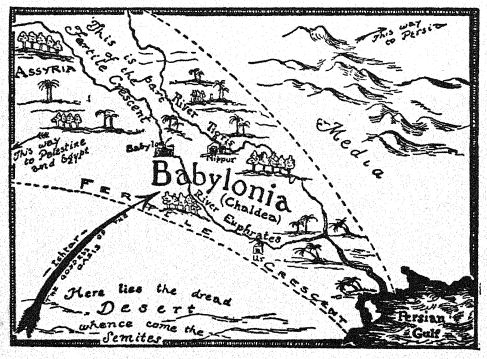

TO trace the further advance of religion we must now shift the scene to a land far distant from the primeval forests of the Celts. We must go to ancient Mesopotamia, that verdant region between the great rivers of the Near East, where dawn had already broken what-time night still reigned in the West. The religion of Babylonia, even though far more ancient than that [ p. 66 ] of the Celts, was in almost every respect far more advanced. From long before the beginning of recorded history, religion seems to have been further advanced in the East than in the West. For reasons which we cannot at all make out, the Orientals, especially the Semites, seem to have had a peculiar genius for religion. They were bedouins, those Semites: a lean, hungry, harried race forever roaming the desert vastnesses of Arabia in search of another place and another time to die. And it was they, most probably, who laid the foundations of Babylonia’s religion. Thousands of years ago, when some of them struggled out of the barren desert and obtained a foothold in the lush meadows of Mesopotamia, they brought with them their old desert religion. It was then little more than a crude animism, [ p. 67 ] with Ishtar, “Self Waterer,” the spirit of the oasis, as the chief deity, Ishtar, who was a goddess, probably had the spirits of the wind and snn and moon as husbands: and certainly she had Tammuz, the spirit of the date-palm, as her lover. We cannot be certain, but it seems rather likely that most of the other important deities then were also goddesses. This must have been because the primitive Semites were still in the matriarchal stage of pre-civilization. Wherever the heads of their families and clans were the mothers, not the fathers, quite naturally the chief spirits were imagined to be goddesses, not gods.

But once the invaders from the desert came to feel at home in verdant Mesopotamia, and began to mingle more or less freely with the non-Semitic natives, their religion took on a quite altered aspect. The matriarchal form of society gave way to the patriarchal, and as a natural consequence the goddesses were changed to gods. The chief deities chosen for the newly created cities were usually masculine. Sometimes they still retained the feminine names by which they had been known in earlier days, as is seen in the case of Ningirsu, literally “Lady of Girsu,” who was the very masculine god of the city of Lagash. Or if the deities managed to persist in the new social order as females in fact as well as name, they took on altogether new functions. A population no longer living in the desert, for instance, had no longer any reason to worship the spirit of the desert oasis — so a star instead of an oasis was given to Ishtar as a home. …

But the Babylonians by no means contented themselves with merely remodeling the old gods. They [ p. 68 ] manufactured new ones, too — hundreds of them. Even to list the chief of them — Ningirsu, Bel, Shamash, Nabu, Marduk, Anu, Ea, Sin, and the rest — would be quite tiresome. The idea of one great god with universal sway seems hardly to have occurred to the people. Again and again, as one city after another became dominant in the empire, one god after another became chief in the pantheon. For instance, so long as Babylon was the capital of the empire, Bel-Marduk, the god of Babylon, was considered the superior deity. But never more than superior: never One alone, and beyond challenge. Occasionally not a single god, but a group of three together was worshipped as superior: Anu (sky), Bel (earth), and Ea (sea) ; or Shamash (sun), Sin (moon), and Ishtar (the star Venus) … Age after age new trinities of that sort arose.

¶ 2

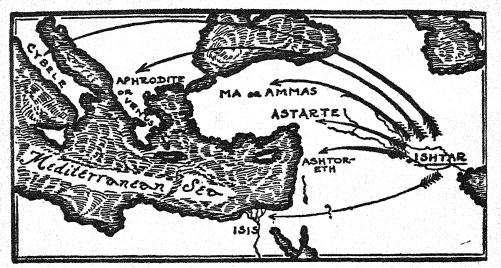

BUT from beginning to end, one deity remained supremely popular at least among the plain people of Mesopotamia. That deity was Ishtar, the great mother of the gods, the spirit of sex and fertility, the very principle of life itself. Many other early peoples worshipped some such mother goddess, for the power of reproduction among plants, beasts, and men, remained unflaggingly the most vital and engrossing power of all. To be able to control it meant to live; to fail meant to die. Little wonder, therefore, if everywhere in the world, in Mexico and the Congo, in Ireland and the Malay isles, we find the people groveling at the feet of some sexdealing, life-breeding spirit.

In Babylonia and throughout the Levant the people [ p. 69 ] seem to have bowed down to it inordinately, and sex rites in honor of Ishtar — or Astarte, Ashtoreth, Isis, Cybele, Venus, and Aphrodite, as the goddess was known in the various lands — were counted of primary importance. In Babylonia itself it was required that every woman, rich or poor, should submit at least once in her life to the embraces of a stranger. She had to wait in the courts of a temple of Ishtar until some man bought her for an hour, and then she had to dedicate to the goddess the wages earned by her harlotry. Without performing that rite a woman was imagined to be incapable of bearing children, and was therefore unfit to marry. As a result, the temple-courts were simply choked with desperate virgins; and the priests of the Ishtar cult, who often were paid to play the part of the welcome stranger, grew enormously rich. . . .

[ p. 70 ]

The difference between this Babylonian cult of Ishtar and the primitive Celtic cult of Bridget was entirely one of degree, not of kind. Both were inspired by dread of the same evil, sterility; and both sought to attain one end, fecundity. But one, the Babylonian, was far less primitive than the other — far less wildly promiscuous and bestial. The Babylonian rites were conducted within the confines of stone temples, not out in the furroughs of the torch-lit fields; and they were hedged in with a thousand rules and watched over by a myriad of priests. Between those priests and the Celtic Druids there was again a difference only of degree. The Babylonian holy men were merely shamans of a more advanced type. They still were little more than magicians and medicinemen; but they had evolved a highly intricate technique, and had developed a grotesque psuedo-science to support it. They had somehow hit on the idea that the constant changes in the heavens bear some subtle relation to the happenings here on earth. Not merely to the vast geographic happenings on earth (that much would be scientifically quite valid), but even more to the petty fortunes of all the creatures swarming over it. All human souls were believed to be hitched for weal or woe to stars, and the chief concern of the priests was, therefore, star-gazing. That sorry deceit called astrology, which still lures the feebler-minded among men, had its first development back there in Babylonia almost four thousand years ago!

¶ 3

BUT the Babylonian priesthood did not confine its interests to the stars in the heavens. On the contrary, [ p. 71 ] it also reached out and tried to control the most mundane things on earth. It truckled to the conceits of the rich and preyed on the terrors of the poor. It owned magnificent and costly brick temples that rose to the very heavens in ornate terraces — veritable Towers of Babel they were — and regularly sacrificed to the idols that stood in them. There were many divisions in the priesthood, each with its own particular function. Certain of the clerics awoke the gods in the morning, washed and dressed them, and offered the elaborate sacrifices; others sang the hymns and chanted the spells; to others was assigned the task of fructifying the barren women who waited in the temple courts; still others read horoscopes and told fortunes. That many of the priests were fools and more were knaves, is to be taken for granted. That many gouged the widows and forgot the orphans, is to be expected. After all, religion to the Babylonian was not a matter of noble sentiment, but a sort of complicated insurance business; and its priestly solicitors and agents were, as Americans would say, out to get “all there was in it for them.” Their extortions, especially for fortune- telling, sometimes grew so flagrant that kings had actually to pass laws to control them. Inscriptions tell us that already before 2800 B. C. King Urkagina had to legislate against priestly profiteering! …

But it must not be imagined for a moment that the great priesthood of Babylonia was unrelievedly lecherous and low. One cannot read their ancient hymns without realizing that at least some among their band were men of what we vaguely call “spirituality” and “religious insight.” Most of those hymns are mere medleys [ p. 72 ] of magic phrases, but others are poems of amazing beauty. Indeed, certain of them ring with tones that are strikingly reminiscent of the Hebrew Psalms. For instance:

The sin which I sinned I knew not;

My God has visited me in wrath.

I sought help, but none took my hand;

I wept, but none gave ear.

To my God, the merciful God, I turn and pray;

How long, O Lord! . . .

O God, cast not away thy servant,

But turn my sin into a blessing.

May the wind carry away my transgressions.

Seven times seven are they —

Forgive thou them! . . .

Now that is no ordinary bit of primitive liturgy. It reveals a reverence for the deity, a humility in the worshipper, and above all a freedom from magical formula that would lead us to think it all a forgery did we not have the very stone on which the Babylonian priests engraved it. Such lines may not be even remotely typical, but they are authentic. And because they are authentic, and they and other lines of like quality were ever written in Bel-Marduk’s courts, the cult of Babylonia must be seen to mark a distinct advance in the evolution of religion.

¶ 4

BUT we must not exaggerate the extent of that advance. Babylonia’s cult was distinguished for the intricacy of its priestly organization, the ornateness of its [ p. 73 ] temple ritual, and most especially for the elaborateness of its astrology. In other words, it was distinguished for its legal, aesthetic, and psuedo-scientific features. But in the highest concerns of religion, in theology and ethics, it was still woefully primitive. Somehow it never progressed beyond polytheism; never really far beyond polydemonism. The Babylonians imagined the whole earth to be peopled with demons — with evil genii that stalked and afflicted men with floods and plagues and darkness. The gods themselves were often regarded by the priests as mere snivelling wretches forever hungering for scraps from the temple altars. (That was but natural, for no god can be a hero to his valet.) In one of the Babylonian scriptures the gods are actually compared to the flies that buzz around the sacrificial carcasses. In another place, where the story of the Flood is recounted, they are spoken of as dogs:

The gods were frightened at the deluge;

They fled, they climbed to the highest heaven.

The gods crouched like dogs;

They cringed by the walls! . . .

And ethically the Babylonians were just as primitive. Ritual scrupulousness seemed to them far more important than human rectitude; sacrificial omissions seemed to them far more heinous than moral offenses. Taboos dogged their every step in life, and “bad luck” threatened them at every turn. Every seventh day ^ was regarded as somehow “evil,” and on it special sacrifices were fearfully offered and all manner of special taboos were observed. For instance, the princes were forbidden to go forth on journeys on that day, or to eat meat cooked [ p. 74 ] over a fire. Every fourth of those “evil seventh days” was particularly dreaded, for it marked the beginning of the waning of the moon’s power. On it desperate efforts were made to placate the demons, and thus avert the unluckiness otherwise certain to come with the day. Significantly enough, the Babylonians called it Shabatum, a name strikingly like that given by the Hebrews, to their holy day, the Sabbath. It is highly probable that the Hebrews actually got their Sabbath from the Babylonian Shabatum, for we know they paid little heed to its observance until after they had lived in exile in Babylonia from 586 B. C. to 536 B. C. But note how differently the Hebrews regarded the day. To them it was holy, not evil. The Hebrews told themselves that the Sabbath was a divinely appointed “day of rest,” and though they observed on it many of the old Shabatum taboos, they did so not out of fear of the genii but out of respect for their God. Their New Moon festival was an ocassion for rejoicing, not for added trembling and dread.

The contrast is no slight one. It reveals glaringly the inferiority, the essential primitiveness, of which religious thought in Babylonia never quite rid itself. The Babylonians developed a vast mythology, but they graced it with no ethical meaning. They told many tales about their gods, about the creation of the world, the first man, the great flood, and so forth. But these tales were almost unrelievedly wild, crude, even foul. When we meet them again in the Old Testament — for those stories, like the Shabatum taboos, seem to have been taken over from the Babylonians by the Hebrew exiles — we find them changed almost beyond recognition. In [ p. 75 ] the Bible they are no longer mere bawdy romancings told for the mere joy of their telling, but passionate sermons recited to bring home certain moral ideals. Ethically the Babylonians were little more than grown-up children. Fear still had hold of them and kept them slaves. Even though they were rich and powerful, even though they were the lords of the green earth and thought themselves the masters of the starry skies, still they remained cravens in their hearts. Beneath all their bluster they were timorous and worried. They were afraid . . . afraid. . . .