[ p. 75 ]

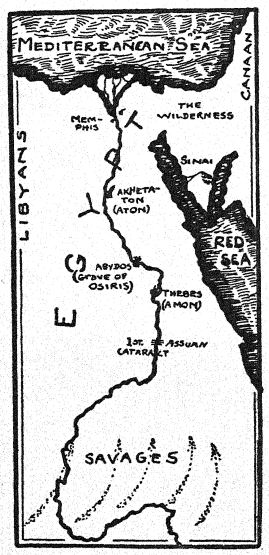

TO trace the further development of religion we must go now from Babylonia to ancient Egypt. Of course, in very early times the Egyptians, like the rest of the primitive peoples of the earth, were simple animists. All things around them seemed to be animated by certain wilful spirits; and to these spirits the Egyptians paid terrified homage. Only a few of the spirits were thought to dwell in natural phenomena such as the sun, the moon, and the great River Nile. The majority were imagined to have their habitation in various species of animals and birds. Each tribe — there seem to have been forty-two of them in Egypt about seven thousand years ago — worshipped the spirit inhabiting some particular species of living creature, and looked to it for protection. One worshipped the ram, another the bull, a third the lion; others worshipped the serpent, the cat, the goat, the ass, the falcon, the hippopotamus, the pig, and the vulture. Evidently the earliest religion of Egypt must have been a totemism rather [ p. 76 ] like that of the American Indians, each tribe being named after the animal which it held sacred, and which it mayhave looked on as its spiritual ancestor.

But as civilization advanced among the Egyptians, the primitiveness of their totemism began to disappear. The “powers” began to be thought of no longer as mere animals but rather as gods symbolized by animals. The idols, which originally may have been simple images of beasts, were now carved to represent bodies whose heads alone were those of beasts. Or occasionally — as in the case of the sphinx — the body was still that of an animal, but the head was human. And when, after much wandering, the tribes settled down at last in what became their fixed provinces, these half-animal gods became localized. For instance, Amon, who was symbolized by a ram, became the god of the village of Thebes; Ptah, the bull-god, became the deity of Memphis; Set, the ass-god, became the protector of the village of Ombos. In every town the stone temple of the local god towered over the mud hovels of the people. It was literally the “house of the god,” and the priests in it were called the god’s servants. Morning, noon, and night they waited on the idol that glowered in the terrifying dimness of the inner sanctuary. They washed and dressed it in the morning, gave it food, and flattered it with hymns. At night they removed its vestments and figuratively put it to bed. Stony and immobile as it was, the idol nevertheless seemed to them the dwelling place of the most dreadfully potent force in the world. Perhaps the more astute of the priests, those who had served longest and profited most by the cult, knew better. But certainly the people did not. The people, [ p. 77 ] the myriads of sweating serfs and starving peasants — they believed. Unalterably they believed that lodged in the idol there was a spirit that could bring them life or death. Probably the majority of the priests believed likewise, for the proverb “as the people, so the priest” states a truth that holds for all races, not merely the Hebrews. Rare indeed, therefore — and silent as night — must have been the doubters in those days of unbridled faith. . .

¶ 2

BUT what happened later in many other lands happened of course in Egypt, too. Though the fear of terrorful spirits never ceased to be a stark and ominous reality, the exact identity of those spirits wavered and continually changed. The fusion of the Egyptian tribes brought with it a fusion of the tribal deities. The temples became the houses not of single gods, but of whole families. Usually the original spirit of the temple was given a neighboring goddess for a wife, and a minor godling for a son. Or sometimes he was given two goddesses as wives. And that tendency, begun on so small a scale, was carried on until at last one god was exalted over all the rest in Egypt. Centuries before the Hebrews came up out of the night of desert savagef*, we find the Egyptians already groping their way toward the idea of a monotheism, a One God. It was political rather than philosophical considerations that impelled the Egyptians in such a direction. As soon as some tribal chieftain managed to fight his way to the throne of the land, so soon did he try to set his tribal god on the throne of the heavens. And to give permanence to [ p. 78 ] the arrangement, he naturally was driven to attempt the destruction of all the defeated but still menacing gods. Usually he tried to wipe them out by declaring them to be merely so many vagrant manifestations of his own deity. Or else his priests invented elaborate mythologies to prove that his god had been the very first in the universe, and had actually created all the other deities. Century after century such stratagems were resorted to. Every king cherished the same futile hope of establishing his dynasty forever, and for that reason every king tried to prove his god to be the only one worthy of worship. . . .

¶ 3

BUT no one of the attempts ever quite succeeded. Even the valiant attempt of the famous King Ikhnaton came to naught. This Ikhnaton, who reigned in Egypt from about 1375 to 1350 B. C., has not unjustly been called the first individual in human history. With amazing clarity of vision and singleness of purpose he set himself the task of making the religion of Egypt an absolute monotheism. He broke completely with the polytheistic past, denying all the favorite old gods and suppressing their cults. Only Aton, the Sun-God, was recognized, and to Him every human knee was made to bend, and every tongue to give homage. The king gave up the name, Amonhotep, by which he had been known all his life, simply because it contained the name of the old god, Amon. Instead he called himself Ikhnaton, which meant “Spirit of Aton.” Because his old capital was the center of Amon worship, the king gave that up, too. He built himself an entirely new city, calling it [ p. 79 ] Akhetaton, meaning “Horizon of Atom” He tried to revolutionize every phase of Egyptian life, spurning all the old conventions and creating by fiats even a new art and literature! . . .

Of course, the priests of the fallen gods fought him bitterly, for he had taken the bread — and honey — right out of their mouths. But they could do little, for the power of Ikhnaton was absolute in all his empire. He sent stone masons all through Egypt to erase the names of the old gods from the temples and pyramids. He caused even his own father’s name to be obliterated because it contained the name of Amon! And in his new capital he built a splendid temple to his One God, Aton, adoring him with sumptuous sacrifices and with hymns of surpassing beauty.

Thy dawning, O Living Aton, is

beautiful on the horizon. . . .

O, Beginning of Life, Thou art all,

and Thy rays encompass all. . . .

Manifold are Thy works, One and Only

God, Whose power none other possesseth;

the whole earth hast Thou created

according to Thine own understanding.

When Thou wast alone didst Thou create

man and beast, both large and small;

all that go upon their feet, all that

fly on wings; yea, and all the foreign

lands, even Syria and Kush besides this

land of Egypt. Thou settest all in their

place, and providest all with their

needs. . . . [though] diverse are their

tongues, their forms, their skins. . . .

O how goodly are Thy designs, O Lord,

that there is a Nile in the sky for [ p. 80 ]

strangers and for the cattle of every

land. … Thou art He who art in my

soul; Thou art the life of life;

through Thee men live!

So did he sing, that great Egyptian heretic, centuries before ever a Hebrew psalmist had appeared on earth! But none there was to sing so after him. When Ikhnaton died, Aton also died. The priests of Amon and Re and the other old gods quickly came into their own again, setting up their old altars, and chanting their old spells. The very son-in-law of the man who so zealously altered his name from Amonhotep to Ikhnaton thought it wise to change his own name from Tutenkhaton back to Tutenkhamen. Once more Thebes was made the capital, and its priesthood waxed fat with might entire population (one out of every fifty Egyptians!) [ p. 81 ] became actual slaves in the temples; and a seventh of all the arable soil in the realm became temple property. The high-priests grew more powerful year by year, and in the end one of them actually seized the crown! . . . And thus was all the labor of that royal heretic, Ikhnaton, made to come to naught.

Yet a vestige of that impetuous reform did endure. The idea of a monotheism, of a single God in all the universe, was never quite blotted out from Ikhnaton’s day on. Somehow the idea lingered in the land, persistently affecting at least the language if not the life of the priests. More and more the old gods were merged together; even their names were hyphenated. Amon and Re were spoken of as one from then on — Amon-Re. And what was more important, this composite god was now thought of not as a spirit animating merely, a golden disc in the heavens, but as a spirit flaming in the hearts of men. Not merely in the hearts of kings, but in the hearts of men — all men! . . . . So the impatient heretic, the tyrant reformer, Ikhnaton, though he failed, nevertheless succeeded. A little, perhaps the veriest trifle, of that which he had preached while he was yet alive remained on after his death. But it was an enduring trifle. …

¶ 4

THE leaning toward monotheism was not, however, the chief distinction of old Egypt’s religion. One must realize that the tendency in that direction was marked only in the upper levels of religious thinking in Egypt It arose partly out of philosophical reasoning and largely out of political necessity, and therefore it did not even touch the life of the plain oennle in the land. So [ p. 82 ] far as the Egyptian masses were concerned, no tendency toward monotheism was even existent. The masses laboring on the banks of the Nile, like the masses everywhere else, were not much given to abstract theologizing. Harried and hounded by a myriad terrors, they could do no more than reach out into the blue for help, and then trust to luck that they had clutched for it in the right direction. The masses had neither the time nor the brains to speculate on the nature of the spirits who gave the help, or the manner in which they gave it. Questions of such a nature had to be handed over by them to the priests and learned men to solve. It was not the peasant’s part to reason how; his was but to fear and bow. . . .

From first to last, therefore, the masses of Egypt continued to worship their innumerable half-animal gods, paying heed neither to the fiats of kings nor the disquisitions of priests. Of course, the mob had its favorite gods, differing at various times and in various localities; for with the unconscionable fickleness characteristic of mobs, it dropped its favorites about as fast as it took them up. Only one god, Osiris, managed to hold his place in the affections of the people throughout Egypt’s long history. Originally this Osiris seems to have been the spirit who made the crops grow, the god of vegetation comparable to Tammuz of the Babylonians. As such he was of great importance almost from the beginning, for the Egyptians were an agricultural people who depended on the crops for their very life. As time went on, therefore, Osiris assumed a place of more and more importance in the minds of the people, until at last they came to look on him as the Divine Lord of the Nile [ p. 83 ] Lands, the God of Justice and Love and nurturing LightIn large part his exaltation to this rank was due to the spread of a significant myth among the people. The story was told how once on a time Osiris, this god of nurturing Light and Good, was treacherously put to death by Set, the god of withering Darkness and Evil. When Isis, the loving wife of Osiris, learnt of the murder, she went up and down the land to find the body of her lord, lamenting sorely as she went, and weeping until the Nile actually overflowed its banks. Isis found the body at last and buried it; but not very carefully. As a result, while she was away looking after her fatherless son, Horus, the corpse was stolen from its grave. The wicked Set got possession of it, dismembered it thoroughly, and then hid each fragment in a different place. So then Isis had to traverse the land a second time, seeking out the pieces of the body, and burying them more safely this time in a sealed tomb. And thereupon Osiris came to life again! He was miraculously resurrected from death and taken up to heaven; and there in heaven, so the myth declared, he lived on eternally!

Obviously that myth had its origin in an attempt to explain the annual death and rebirth of vegetation. Every autumn seemed to witness the foul murder of all that was good to man, and every spring seemed to mark its resurrection. And the Egyptians, like most other races, came to look on that recurrent rescue of the earth from bleakness, cold, and famine, as the most wondrous miracle in the universe. Even the dullest serfs could not fail to be bewildered by it; even the most cloddish minds could not but be eager for some story explaining [ p. 84 ] it And having agreed upon such a story, those fellahin felt impelled for some reason to dramatize and enact it year after year. Every spring at Ahydos the drama of Osiris was enacted by the Egyptians in a stirring passion play, much as the peasants in Oberammergau enact the drama of Jesus even today. . . .

There is small cause to wonder that in time this folkdrama, rooted as it was in the earth’s greatest mystery.

became the very core of Egypt’s religion. Somehow its plot seemed to give the key to the whole riddle of life and death. The Egyptians reasoned that if it was the fate of the god Osiris to be resurrected after death, then a way could be found to make it the fate of man, too. Of course I All one had to do was be buried properly. If only a man’s soul were committed safely into the [ p. 85 ] hands of Osiris, and his body embalmed and preserved in a tomb, then some day of a surety the two would get together again, and the man would walk the earth as of yore. At least, so it came to be believed in Egypt as long as four thousand years ago.

In the beginning, however, only the kings were believed to stand a chance of resurrection, for they alone were thought to have souls. That was why in those days the kings alone were embalmed and mummified. Huge pyramids were built to shelter their royal bodies against the day of their resurrection, enormous structures of brick and stone that still stand today, and no doubt will still be standing centuries hence.

But finally the day of the despotic pyramid builders came to an end, and a spirit of democracy crept into the land. The bliss of immortality that had formerly been reserved only for kings was then promised to all men. It came to be admitted that every man had a soul that lived on through the winter of death; and for that reason every man’s body had to be preserved in the hope of ultimate resurrection. Even the bodies of those animals that were deemed sacred to the various gods, the bulls and rams and cats and crocodiles, were preserved in that hope. At Beni Hasan so many mummified cats were laid away that nowadays the cemetery is used as a quarry for fertilizer!

¶ 5

THE dead were thought to lead a curious double life, one on earth and the other in heaven at the same time. The earthly existence was carried on by the mummy in the tomb, and its conservation demanded that food be [ p. 86 ] laid out for its nourishment at regular intervals. The horridest fear in the heart of the dying Egpytian was that his heirs would neglect to perform that service, and often contracts were made with utter strangers, with professional tomb-tenders or neighboring priests, to keep the mummy’s larder replenished. And for fear that even these solemn contracts might be broken, the tombs were carved with piteous verses begging the passer-by to offer if not a meal at least a little prayer — “which costs only the breath of the mouth” — for the neglected dead. . . . The heavenly existence of the dead was carried on in the realm of Osiris, and it was described in considerable detail by the Egyptian theologians. It was believed that on death the soul of a man set out at once to reach a Judgment Hall on high. Evil spirits tried to waylay it on the journey, but any soul adequately provided with magic formulae could evade them all. With these spells the evil spirits could be dodged or fought off until finally the soul attained the Judgment Hall and stood before the celestial throne of Osiris, the Judge. There it gave an account of itself to Osiris and his forty-two associate gods. Any soul that could truly say: “I come before ye without sin, and have done that wherewith the gods are satisfied. I have not slain, nor robbed, nor stirred up strife, nor lied, nor lost my temper, nor committed adultery, nor stolen temple food. . . I have given bread to the hungry, clothes to the naked, a ferry to him who had no boat” — if in sincerity it could say all that, then the soul was straightway gathered into the fold of Osiris. But if it could not, if it was found wanting when weighed in the heavenly balances, then it was cast into a hell, to be rent to shreds [ p. 87 ] by the “Devouress.” For only the righteous souls, only the guiltless, were thought to be deserving of life everlasting! . . .

It was an extraordinary set of beliefs, and reveals a moral insight on the part of the Egyptians that must have been unmatched in the world of four thousand years ago. No other people in that day seems to have been capable of conceiving a Judgment Hall where a life of moral innocence, and not merely of ritual propriety, decided the soul’s fate after death. Of course, certain elements in the conception were distinctly primitive; for instance, the idea that no soul, however righteous, could ever reach the Judgment Hall unless well armed with magic formulae to protect it on the way. Such a flaw could not but leave an opening for the introduction of all sorts of superstitious practices. To be on the safe side, coffins were literally lined with those magic formulae, or were packed tight with rolls of parchment on which mystic spells were written. The practice was relentlessly opposed by King Ikhnaton, the heretic, and during his reign it was rarely if ever observed. But once he died, it returned and flourished more rankly than ever before. The ancient Egyptians were not yet so free of primitive fear, or of primitive measures of defense against it, that they dared to rely on their moral guiltlessness alone to win them paradise. They still clung to the notion that there were many evil spirits in the universe which could not be fought off by virtue, but only by magic. They even entertained the notion that die good spirits, too, could be controlled by magic. Certain of their spells were designed for the express purpose of helping sinful souls to dodge the verdict of the Heavenly [ p. 88 ] Judges and sneak their way into Paradise despite their guilt. …

It is not unlikely that the priests winked at these relics of a bygone age, if only because their vogue tended to give them great power. For the priests alone knew how to write the magic formulae, and thus they alone controlled the keys to heaven. At different times they gathered many of those formulae together, and made of them sacred tomes which later came to be known as the “Book of the Dead,” the “Book of the Other World,” and the “Book of the Gates.” In them were set down, not merely magic phrases, but also maps and travel instructions for the dead. They were, so to speak, Baedeckers to the Next World. . . .

So this chapter on the religion of Egypt must end much as did the one on Babylonia. Religion advanced in the valley of the Nile to unprecedented heights. There earlier than anywhere else in the world — at least so far as we know — the idea was conceived of One God ruling in all this Universe. There too was first told the legend of a Lord of Light who died at the hands of Darkness, only to come to life again and go up to Heaven to receive all the righteous there into his embrace. Those were no inconsiderable heights for an ancient people to attain. . . . But the pity of it was that, though those heights were attained, they were not held. Perhaps that decline occurred because the Egyptians sank too completely into thralldom to the priests. (Save for Ikhnaton, Egypt in all her five thousand years of history produced not a single prophetic spirit. And prophetic spirits alone can keep a people on the heights. ) But more fundamentally the Egyptians must have failed because they were still [ p. 89 ] too close to the primitive. Crude fear still had too strong a hold on them. With pathetic earnestness they tried to put their trust solely in the goodness of the spirits; but always they remained a trifle uncertain, tucking away a spell on their person or in their tombs in case of need. They tried hard to believe that virtue alone would win the favor of the gods; but inevitably they added a little incantation, just to be “on the safe side.’’ They could never quite keep from slipping down into the slough of magic. No matter how hard they tried, they could never for long hold to the heights. For even they were still not at home in the universe — even they were still afraid . . . afraid. …