[ p. 89 ]

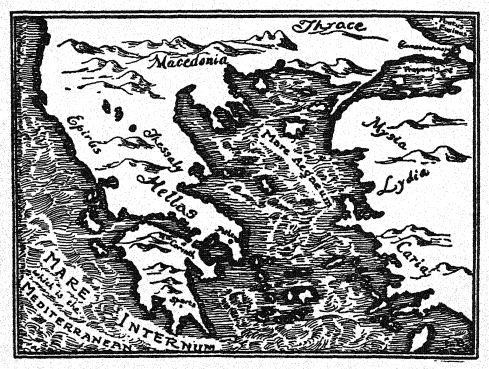

AND now we come to Greece, that little land of broken valleys and sea-swept cliffs wherein ancient civilization climbed and climbed until it reached its very zenith. In the beginning its religion was naturally a terrorful worship of the spirits supposed to dwell in stones and trees — just such a worship as obtained everywhere else in savage times. The inhabitants of the land then were people whom modern scholars call the Minoans, a race whose writing has not yet been deciphered, and whose history and religion are consequently but little known. Judging from remains discovered in Crete and the Aegean Islands, the chief deity of the Minoans seems to have been a goddess who, like Ishtar of the Babylonians, was an impersonation of the principle of fertility, or motherhood. But the Minoans had numerous other deities besides her, some of them gods and most of them goddesses. Only with die coming of the Indo-European Greeks [ p. 90 ] does the religion of the peninsula become better known to us. These invaders were of the same stock as the Hindus and the other Aryans, and when they swept southward from Central Europe sometime before 1200 B. C., they brought with them their sky-god, Zeus Pater, and all their other old Aryan deities. But once established in their new home, they speedily merged their religion with the one already existing in the land. They adopted the deities of the native Minoans, calling them all relations of their own sky-god, Zeus Pater. The great fertility-goddess of the Minoans was named Rhea and called the mother of Zeus; another goddess, Hera, was made his wife; a third, Athena, was called his daughter. Two of the native gods were named Poseidon and Hades, [ p. 91 ] and were given to Zeus for brothers; another, Apollo by name, was declared his son. Even the crude idols of the Minoans, obvious sex symbols sacred to the goddess of fertility, were taken over by the newcomers. And thus a new religion came into being. In part it was a fear-riddled, magic-mongering cult rooted in the halfcivilization of the Minoans; and in part it was the shallow, light-hearted, myth-making cult of the barbaric Greeks.

For many centuries the second element remained dominant. When the minstrels of classic Greece sang of the gods, they sang of glorified men: gay, lustful, brawling heroes, who sported about on Mount Olympus without giving the slightest heed to morality or property. And there seems to have been no thought of any compelling tie between the people and the gods. Even centuries later the philosopher Aristotle solemnly wrote, “to love God would be improper.”

But if the early Greeks did not love their deities, neither did they greatly fear them. The tales that are called Homeric reveal almost no trace of any terror of the gods. The people seem to have regarded Zeus and his divine family with a measure of fondness, perhaps even with a measure of awe — but nothing more. Perhaps this was because the priesthood never attained any great power in ancient Greece. A well-organized priestly caste inevitably succeeds in hammering the “fear of the gods” deeply — usually too deeply — into the hearts of the people. But no such caste ever existed among the Greeks. The priests in the land were but minor state officials who differed very little from laymen, save on the rare occasions when sacrifices had to be formally offered [ p. 92 ] to the gods. The images of the gods were carved by artists who thought only of beauty, not by holy men bowed in terror or reverence. The cult was solemn and dignified, but far from intensely moving. The ornate sacrificial etiquette that marked the religions of Babylonia and Egypt was largely unknown in early Greece.

¶ 2

BUT though that shallow, light-hearted cult managed to persist for a while, ultimately it had no alternative but to fade away and be forgotten. For it lacked warmth and fervor. It had too little of that commingled terror and hope, too little of that blasting fear and febrile yearning, which is the stuff whereof enduring faiths are made. Essentially the cult was without point, without much value or helpfulness in the business of keeping alive. It held out neither a comforting hand nor even a threatening fist to man. And therefore it could not possibly keep alive itself. Had it possessed an elaborate ritual and a politically powerful priesthood, no doubt it could have subsisted much longer than it did. (Well-intrenched ecclesiastical systems have protracted the life of many an outworn religion.) But the Olympian cult, as we have already seen, had never been able to develop such a preservative for itself. For a while it hung ripe on the bough of Greek thought, and then the people allowed it to fall to the ground and rot there. Both sage and boor, aristocrat and slave, turned from it in despair. None of them found it to be the indispensable viand that sustains life and makes it worth while. To none of them could it bring salvation. So it died. . . .

[ p. 93 ]

But it did not die of a sudden. Already by the sixth century B. C. the vanity of the Olympian cult was sensed by the keener minds in Athens and the other city-states of Greece. But not until the fourth century did it really give up the ghost. And during all those years of its slow disintegration, new approaches to salvation were being discovered by the Greeks. The learned took to philosophy, for they were far advanced in mentality and fully able to extract satisfaction from such a discipline. Had primitive fear swirled higher around them, of course they would never have been capable of being sustained by philosophy. They would have resorted instead to magic spells for help, and gone clutching bewilderedly at mythical spirits. But the flood of fear had subsided, and only a slough of despond was left. It was not terror, therefore, so much as disquiet that spurred the learned folk of Hellas to go seeking salvation. The advance of the race out of the hazards of the primeval forest had already made life possible — but it had not yet made life reasonable. As a result, the Greek sages were intent not so much on self-preservation as on self-realization. . . .

And that was why they turned from the childish vanities of the Olympian cult to the rigors of philosophy. Through philosophy, that trying discipline of the mind which indefatigably gropes and claws its way in the hope that at last it can uncover the why of all things — through philosophy the learned of Greece sought to attain that sense of security which we call salvation. A whole galaxy of sages deployed their forces in the realm of the spirit, each of them bent on finding a means not ©f material protection but of spiritual satisfaction, each [ p. 94 ] of them gralling not so much for a way of living as for the way of Life.

We are tempted to go off here at a tangent, and speak at length of the great philosophers that ancient Greece produced. There was first of all Thales, who lived fully twenty-six hundred years ago; then there were Pythagoras, Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Empedocles; there were Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Each of them, in his own way and according to his own lights, went groping, searching, after that sense of security without which life is either terror or vanity. For the most part they did not even bother to discuss the old religion and the old gods. They simply shrugged their shoulders at their mention, and passed them by. Occasionally a dramatist, like Euripides, stopped to take a fling at them; but the philosophers, as a general thing, let them alone. They struck off along paths that led to new gods, or rather, to a new idea of god, of the One God, whom their new-found logic told them must be the ultimate source of power in all the universe. Almost without exception the sages seem to have been conscious of some such unifying God. Thales called Him “the Intelligence of the world.” The Stoics described Him as “the Helping of man by man.” Plato called Him “the Idea of Good.” And so most of the other philosophers. . . .

¶ 3

BUI tire plain people, the masses, could not follow along the steep, narrow paths of hard reason up which the philosophers clambered. Indeed, they sometimes resented the temerity of those philosophers, and violently dragged them down. They exiled Anaxagoras, and [ p. 95 ] Protagoras, and put the great Socrates to death. They could not fathom what those philosophers were after. The plain people of Greece were, after all, still quite primitive. They were not yet capable of wondering as to the ultimate reason for living; they still wanted to know just how to keep alive. With them the vital problem was not self-realization, but still self-preservation. For they were still not at home in the universe. They were still afraid! …

Quite naturally, therefore, the plain people fell back on magic. The old Minoan element, that dark mumbling of spells between chattering teeth, came sweeping back over the land in a mounting wave of hysteria. Even in the gay, sunny days of Olympian worship there had always been among the plain people a cowering worship of ghosts. There had always persisted a rooted belief in the power of certain evil spirits to maim, sicken, and kill; and always there had been the desire to placate those spirits with sacrifices, or drive them away with spells or a good beating. But now that primitive demon- worship no longer lurked in haggard woods or slum alleyways. It crawled out and began to flaunt itself in the open. And there was none left in all Hellas to drive it back. Like some loathsome nocturnal beast out of the jungle it bared its fangs and went ravishing through the land. . . .

And side by side with this demon- worship there came a second monster of faith: an ecstatic, drunken saviorworship. In origin it seems to have been foreign to Greece, an exotic thing from the hinterland and the orient; but for all that it did not want for prey. The ruck and scum of a hundred foreign populations had been [ p. 96 ] dragged in. chains to Athens and the other Greek cities. Hordes of serfs and slaves festered in crowded slums, or slaved in mines and fields and forests. And eagerly, frenziedly those hordes threw themselves in the path of this strange beast. Secret cults of mystic salvation arose in every corner of the land, little sodalities preaching a religion of ecstatic hope and orgiastic practice. They were called “Mysteries,” and almost without exception they circled around the idea of a god who died and was resurrected. As we have already seen, that idea was obviously inspired by the sight of the annual death and rebirth of the crops. The idea was known and gave rise to cults not alone in Egypt, but in almost all the other Mediterranean lands. Indeed, throughout the world one discovers signs of its quondam prevalence. And that scattered dissemination was hardly due to widespread borrowing from a single source; rather it was the result of a widespread clutching in a single direction. No matter how far the races of man may be scattered across the face of the earth, they are all hounded by similar dangers and cursed with similar fears. As a consequence they have all been forced to hit on more or less similar means of defense. Mankind everywhere, in Mexico and Iceland, in Zululand and China, makes more or less the same wild guesses in its convulsive effort to solve the riddle of existence. And that is why we find this complex idea of a slain and resurrected god common in many parts of the world. It was one of those guesses, one of those blindly hopeful snatches after security, which a race drowning in insecurity instinctively felt forced to make, no matter where it dwelt In very early times that idea flourished not alone [ p. 97 ] among the Babylonians and Egyptians, but also among the barbaric tribes in and around Greece. Among the latter it gave rise to a whole farrago of myths telling how some god — Dionysus, Zagreus, Zabazius, or Orpheus — had once upon a time gone madly careering through the woods, had been torn to pieces and destroyed, and then had been magically restored to life again. And as a corollary of those myths there had arisen the companion belief that by imitative magic every human being could repeat that divine experience. Every mortal could take on immortality simply by doing as the god had done. A man had only to eat the flesh and guzzle the blood of the animal sacred to his savior-god, whirl around in orgiastic passion, hack at his own flesh in madness, and shout, scream, howl to the skies, and then in a moment of frenzy — an “enthusiasm” it was called in Greek — he was of a sadden overwhelmed by the conviction that he actually was the god! He had to experience a mystical orgasm that sent silver, sensory storms sweeping through his flesh, that set a diapason of nerves quivering in his rigid body, that lifted him up, up, up, till with a sob of unendurable ecstasy he felt all the evil literally gush out of his being . . . and then he knew himself at last to be — divine! …

¶ 4

SUCH was the wild flame that burnt in most of die mysteries; and one cannot wonder that myriads in Greece went flocking to it once the sun of Olympian worship could no longer warm their blood. It gave them hope and cheer; it won them Paradise. It gave [ p. 98 ] them life — life in some other and better world — life immortal and ever-blessed. And that was, after all, the ultimate want of the submerged masses in Greece. They had given up this world as hopeless, as utterly barren of all chance of joy for them. Those wretched helots, ground in the dust beneath the heel of the upper classes, could not possibly see any remaining hope of peace for them in this vale of tears. But being still human, still charged with that insensate Will to Live which is life’s primal spark in man, they could not sit supinely by and let death overtake them. No, they had still to want for life, for restful, blessed, enduring life. Only they had perforce to want it in some other world. . . .

Now the old Olympian worship had done nothing to satisfy that want. Only the half-divine heroes — and not all even of them — were assured a life in the Elysian Fields when death took them from this earth. Ordinary men, no matter how righteous and worthy, were all consigned to Hades after death. There in dank subterranean realms their spectral forms, bereft of bones and sinews, swept “shadow-like around,” and chattered tonelessly like so many bats. They knew no bliss, no rest, no peace — only unbroken gloom and misery. No wonder Achilles cried: “Nay, speak not comfortingly to me of death, O great Odysseus. Far rather would I live on earth the hireling of another, with a landless man who is himself destitute, than bear sway over all the dead that be departed!” . . . But the new worship, these mysteries come down from Thrace or across the sea from Egypt and Asia Minor, told a far different tale. They declared that for every man, no matter how poor or vicious, there was a place in heaven. All one had to [ p. 99 ] do was to be “initiated” into the secrets of the cult, purifying oneself by baptism in blood or water, dancing the sacred dances, partaking of the sacred offering, and finally gazing on certain very sacred and mysterious cult objects. Once a man performed those rites, then salvation was assured him, and no excess of vice and moral turpitude could close the gates of paradise in his face. He was saved forevermore! . . .

Perhaps as early as 1000 B. C. the Greeks were already practicing what were called the Eleusinian mysteries; but these were of a relatively sober and formal character. Not until the sixth century B. C. do we hear of more violent and primitive mysteries in Greece, and then they are associated with the name of Orpheus. They were imported largely from Thrace, where they had long been indulged in by barbaric tribes; and the faith-hungry Greeks took to them with avidity. For one thing, there was the element of dread secrecy about these strange mysteries — and secrecy has always been enormously attractive to inferior minds. Only those who were solemnly initiated into the cult could have any knowledge of its secrets, or enjoy the immortal bliss which that knowledge was supposed to confer. All others were condemned to writhe forever in a foul, loathsome hell. . . .

These Orphic mysteries therefore flourished luxuriantly, as did the many other mysteries that later invaded Greece. When the cults of the Egyptian Osiris and of the Phrygian Attis were introduced, they too won initiates by the thousand. It was inevitable that they should do so, for the lure they held out was irresistible to the people. Before the eyes of a mob of low-caste [ p. 100 ] peasants and slum-dwelling slaves they dangled a high promise, a glittering hope. They offered divinity, immortality, paradise, and all at the price of orgies which seemed in themselves a delirious delight. How then could they possibly be resisted? . . .

And the vogue of those irresistible mysteries brought the ancient religion of ancient Greece to an end. Only the mysteries survived, increasing in complexity generation after generation, and spreading throughout all the lands bordering the Mediterranean. Even after Christianity came they still flourished. Indeed they almost made Christianity itself another mystery.

But that is another story. . . .