[ p. 191 ]

BUT the religion of China today is neither Confucianism alone, nor Taoism — nor even a combination of the two. A third element long ago entered into the amalgam: Buddhism. Sometime in the second century B. C., after having made its way through Afghanistan and Turkestan, Buddhism finally entered China. It did not spread at once, however. Buddhism then was not yet sufficiently bedizened with easy doctrines and lovable idols for it to have any great proselyting power. But by the second century A. D. it had become an entirely new religion, very generously Salvationists and frankly compromising: and then it spread with great rapidity.

[ p. 192 ]

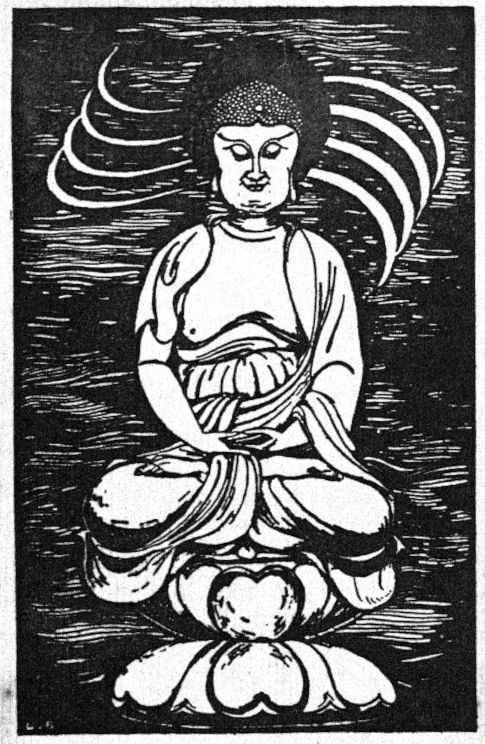

The new Buddhism seems to have had an irresistible lure for the people of China. It had comforts to offer that their own old religions knew nothing about. For one thing, it offered them a very personal and personable god, an idolized Buddha whose serenely placid face and gracefully rotund body could be seen and kissed and kow-towed to in every temple. Confucianism allowed neither idols nor temples. Sacrifices were offered only to tablets, and on altars under the open sky. But this new religion from India brought with it a whole galaxy [ p. 193 ] of attractive idols, and a whole art of temple architecture.

Then, too, Buddhism had a great deal of information to impart concerning life after death. Confucianism, for all its eagerness to obtain aid from the dead, had nothing at all to say concerning their abode. But Buddhism had a very wonderful heaven and a very terrible hell of which to tell, and made prayer for the dead a desperately important jbpmmbm A fter the comBuddhism the Chinese in their worship of the ancestors began to pray for the souls of the dead, as well as to them.

At present, even in Chinese homes where Buddhism is not accepted, it is usual for masses to be recited for the peace of the dead.

But the new Buddhism’s greatest attraction lay in the fact that it was so thoroughly a religion of salvation. To poor blind people groping about in the darkness of life, it offered light It told that they had merely to believe in the Buddha, in was called the “Enlightened One,” and straightway all would become as day for them. Neither Confucianism nor Taoism had a tithe as much to offer. Confucianism, indeed, had nothing to say concerning [ p. 194 ] salvation. It was so busy telling men how to live that it forgot even to ask — let alone to answer — the question why they should live. And Taoism, fallen till it was a mere slut in the laboratories of alchemists, was no better. Even though it did ask why men should live, it offered an answer that the masses could not possibly fathom. It assured the coolie in the rice-swamp that he lived to make it possible for the emperor and his magicians to go hunting the elixir of life — and that was far from an adequate explanation for him.

So Buddhism — or more exactly, the religion that was called Buddhism seven hundred years after Buddha died — had no very great difficulty in winning adherents in China. From the third century on it flourished openly. Temples and monasteries sprang up throughout the land, and Chinese by the myriad were converted. The governing class, it is true, did not always favor the new faith. It was something new, and from their Confucian point of view it was therefore bad. … In the fifth century dreadful persecutions of the Buddhists took place. Monasteries and pagodas were pillaged and burnt, and unnumbered monks and nuns were deported or put to death. But in a little while came a reaction, and at the beginning of the sixth century the very emperor himself abdicated his throne in order to become a Buddhist monk! In the following centuries the faith continued to fluctuate in public favor. Again and again the mandarins protested against it, claiming it was altogether incompatible with the authentic old Chinese spirit. They accused it also of fostering lewdness, especially in its nunneries. In 884 A. D. violent persecutions broke out again, and Buddhism then suffered a [ p. 195 ] blow from which it never fully recovered. All the forty thousand Buddhist monasteries, temples, and pagodas in the land were ordered to be razed to the ground. Their bronze images, bells, and metal plates were melted down and coined into money, and their iron statues were recast into ploughshares and shovels. As for the monks and nuns — who numbered well over a quarter of a million — they were all summarily commanded to return to secular life or leave the country. And though in later years Buddhism managed to rebuild some of those monasteries and fill them with new throngs of monastics, never did it regain its pristine importance.

¶ 2

SO China today is the land of the “Three Truths”: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Confucianism is largely the religion of the learned classes, and all candidates for civil service appointments are expected to pass an examination in its nine holy books. Taoism and Buddhism are the faiths to which the masses alone render allegiance; but both are little more than a dark cloaca, swarming with spirits, devils, ghosts, vampires, werewolves, and green-eyed dragons. The mind of the Chinese peasant today is simply cluttered up with crowds of jostling demons. Throughout the land one finds the Wu, the demon-chasing priests, eking out a living by uttering spells over the diseased and the maimed. A great dread prevails everywhere of unlucky days and unlucky places. Months, even years, are spent in a terrified hunt to find a lucky plot for the burial of the family dead. (In the days of anti-Buddhist agitation, many a Buddhist monastery was spared by the [ p. 196 ] rulers of the locality solely because its presence was supposed to make the surrounding soil lucky for use as a graveyard) There is a rooted conviction throughout the land that each place on earth has its own feng-Shui, its own “spirit climate.” No house, no grave, no shop can be built without first consulting the Feng-Shui magician as to whether its proposed site is lucky. . . .

And to such a sorry faith has a great old Chinese race descended. Fear is to blame for it, of course. It was fear that picked out China’s eyes, and made her blind And it is fear that now flaps its ghastly wings about her, and makes her clutch at every spirit. Fear . . . fear. . .