[ p. 197 ]

[ p. 198 ]

¶ BOOK FIVE — WHAT HAPPENED IN PERSIA

I. Zoroastrianism

1: The animism of early Iran— did Zoroaster ever Eve?— the legends concerning his life 2 : The gospel of Zoroaster Good vs. Evil — the fire altars — the future life. 3 : The ordeal of Zoroaster — his first converts — death. 4: The corruption of the gospel — ritual — burial customs — “defilement —the priesthood — Mithraism. 5 : The influence of Zoroastrianism on Judaism —on Christianity — on Islam — the Parsees.

[ p. 199 ]

¶ BOOK FIVE — WHAT HAPPENED IN PERSIA

I. ZOROASTRIANISM

THE scene of our story shifts westward, leaving the walled cities and rice-swamps of China and going up to the wild plateau of Iran in western Asia. The first white men in Iran, the region now called Persia, were of the Aryan stock; and their religion was closely akin to that of the Aryans who invaded India and Greece. It was an animism centering in the worship of Ashura, Anahita, Mithra, Haoma, and many other spirits supposed to dwell in natural objects. Just how or where that animism had its origin, no one knows; for no one knows whence the Aryans came. Nor do we know exactly when that animism came to an end, for no authentic records exist as to the history of Iran before the seventh century B. C. All that is known is that a primitive animism arose, flourished and then disappeared — and that for its disappearance a certain man named Zarathustra — or more popularly, Zoroaster — was responsible.

But even that much is not known with indisputable certainty. Some scholars today are convinced that there never was a Zoroaster on earth. They maintain he is [ p. 200 ] but another of those mythical personages conjured up by a later generation to explain some vast religious or political change in its past. Moses, Mahavira, Buddha, Lao-Tze, Krishna, and Jesus, are similarly classed by tVm as figures devoid of genuine historicity, as mere fictional heroes created to dramatize and personify slowly matured and impersonal movements. And it must be admitted that there is no unchallengeable evidence to prove the existence of any one of those colossal figures, no carvujgs in enduring stone, or contemporary records set down on still-existing scrolls. All that remains concerning them are webs of legend and gospel spun by generation after generation of zealous but imaginative disciples. Most of those legends were on the loose tongues of men for ages before they were first set down in writing. And even after that, they no doubt still cam e in for great change at the hands of nodding or overconfident scribes. It is far from easy to base a critical faith on their florid and purely traditional testimony.

Yet most reputable scholars, even of the most critical school, incline to agree that those webs of tradition contain at least a few threads of truth. They do so on the score that the acceptance of the historicity of Moses, Buddha, or Jesus puts less strain on our reason than the alternative of rejection. After all, wherever a new and heretical religion was founded, there must have been some outstanding individual to take the lead in founding it. It is naturally less difficult to believe that effects have adequate causes than to believe that they have not. …

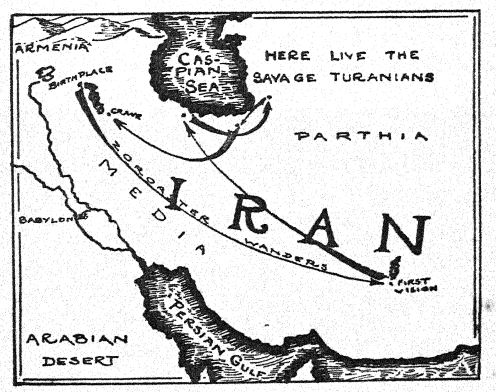

But it is only on such a basis that one can accept [ p. 201 ] the historicity of Zoroaster. It seems less incredible that he did exist than that he did not, for some striking personality must have been at least in part responsible for the tremendous religious transformation that came over the ancient people of Iran. Proof less negative is not at hand. The Persian scriptures, the Avesta, contain a group of hymns called the Gathas which may have been the work of Zoroaster; but just how old they are, no one knows. Tradition gives 660 B. C. as the date of the prophet’s birth; but actually it may even have been as early as 1000 B. C. And tradition gives the northwest of Iran as his birthplace, a place somewhere in the neighborhood of the present Armenian frontier; but actually it may have been at the very other end of the land. Tradition further declares his birth to have been the outcome of an immaculate conception. (It is appalling, how little pride men have in their own species. Rarely can they bring themselves to believe that supreme greatness can spring from their own loins. No, always they must ascribe its paternity to the gods.) An incomprehensible trinity made up of the “Glory,” the “Guardian Spirit,” and the “Material Body,” is reputed to have been responsible for the appearance of Zoroaster on earth. Innumerable miracles occurred while he still lay in the womb of his mother to save him from destruction. Demons sought to hold off the birth, going even to the extreme of trying to choke the child at the very moment of its delivery. But in vain. The prodigy was born, and with its very first breath it uttered a mighty laugh of triumph that was heard around all the earth.

[ p. 202 ]

Zoroaster was indeed a wonderful child — according to the legends. At a very early age he engaged the priests of the old religion in a bitter debate, and routed them. And when grown to the age of youth, he took staff in hand and went off into the world in a quest for righteousness. Sore troubled by the sight of the evil in the world, young Zoroaster could find no peace amid the comforts of his home. So he fled. For three years he tramped the desert trails in search of salvation, of a reason for life. And failing to find it, a great gloom came over him. For seven years then he remained silent, morose and silent, while he brooded over the impenetrable blackness which life had become for him. . . . And then of a sudden, light came. Of a sudden day dawned in his long-benighted soul, and once more he took up his staff and began to wander. But now he was no longer a wanderer seeking for light. No, now he was instead a bearer of light to all others who still sought for it. He went about preaching the salvation that had come to him, and telling how others, too, could attain it. Across the length and breadth of Iran he beat his way, hawking everywhere the gospel that had brought him peace.

[ p. 203 ]

¶ 2

THE gospel of Zoroaster was as thoroughly native to Iran as its frowning mountains and desert winds. It was stern, rigorous, demanding. There was in it neither the florid confidence revealed in the Vedas, nor the livid despair shown in the Upanishads. Rather there was in it a steel-gray valor that could know life for what it really was, and yet could continue to hope. Religions are so varied largely because the earth contains such varied lands and climates. Religion, as we have already seen, is the technique wherewith man seeks to conquer his environment; and therefore it must necessarily vary according to the locale in which it is employed. The religion of the overabundant valley of the Indus could not very well be anything but one of ease. In the intolerable furnace of the Ganges Valley, the religion could hardly be anything else than one of hopelessness. And on the stern plateau of Iran, it could not but be one of fierce courage and struggle. For Iran was a land of perpetual struggle, of perpetual warfare against wind and ice and wilderness. Overwhelming contrasts faced its inhabitants: a great salt desert prostrate with heat at the base of encircling snowpeaked mountains. And the religion there conceived and proclaimed by Zoroaster was likewise one of contrasts. According to it, all the universe was one great battle-ground on which Good and Rad struggled for mastery. On the one side was Ahura Mazda, the Wise Spirit, supported by his six vassals: Good Thought, Right Law, Noble Government, Holy Character, Health, and Immortality. Pitted against him was Angra [ p. 204 ] Mainyu, the Lie Demon, supported by most of the old gods of the popular faith. And midway between the two contending armies stood man. It was absolutely incumbent upon man to choose on which side he would battle: on the side of Good, Purity, and Light, or of Evil, Filth, and Darkness. There could be no slightest compromise or evasion. One had to enlist on one side or the other, just as the beasts, the winds, the very plants were enlisted.

And once each man had chosen his side, then his every word and deed had its effect on the fortunes of the war. It was not prayer but work that was demanded of the worshippers of Ahura Mazda. Their noblest act of devotion was the performance of a task like the irrigating of a desert patch or the bridging of a torrential stream. Ahura Mazda was in essence the spirit of civilization, and the only worship acceptable to him was the spreading of order and stability. He who declared himself on the side of Ahura Mazda was in duty bound to devote all his days to fighting the battle for Light. No mercy was to be shown by him to the enemy, be that enemy some weed or beast or savage from the Turanian wilds. Ahura Mazda was the god of justice, not of mercy, and in his warfare he neither gave nor received quarter. In his service there was no room for sentimentality; one had to be hard and unbending. The one great law of ethics was to give aid to those — and only those — who were also on the side of Good, and never to do them the slightest injury. Even beneficent animals such as those that destroyed rodents, snakes, and other evil creatures, were considered holy and deserving of aid. The penalty for killing a hedgehog was [ p. 205 ] nine lives spent in hell; for killing an otter it was — well, to begin with — ten thousand lashes with a horsewhip. An inviolable sanctity was attached to the life of all domestic animals, especially cows, dogs, and sheep. To care for them and help multiply their number was the devoutest act of faith. …

It was an extraordinary religion, this of the ancient prophet of Iran. It preached a technique of coping with the evils of the universe that was totally at variance with anything ever before conceived by man. Zoroaster had no patience with the old gods, Mithra, Anahita, Haoma, and the rest, and denounced them all as demons. The very word deva, which had always meant “gods,” he made to connote “devils.” (Both connotations somehow found their way into the stream of European languages, and that is why there is still today so close a likeness in sound between “deviltry” and “divinity.”) . . . Only one heathen rite did Zoroaster take over, and that was the veneration of fire. (Some say he came of a family of ancient fire-priests.) But according to the prophet, fire was not a god to be worshipped as it may have been worshipped by the earliest Iranians. No, it was a mere symbol of Ahura Mazda. Fire-altars were to be erected solely as a testimonial to the veneration in which the “Wise Spirit” was held. Zoroaster may himself have gone about the land erecting such altars and reciting the hymns called the Gathas what time he attended the holy flames. But he made it clear that the erecting or serving of a fire altar was not the sole or even the chief approach to the “Wise Spirit.” The chief approach to him was through daily toil. “He who sows com, sows religion.” [ p. 206 ] Laziness was a thing of the Devil. Every morning the demon of laziness whispers m the ear of man. “Sleep on, poor man. It is not time yet. But he alone who arises the first, declared Zoroaster, would be the first to enter Paradise. . . .

No one was left in doubt that there was indeed a Paradise. And there was also a Hell. The true servants of Ahura Mazda would as surely enter the one, it was believed, as the slaves of Angra Mamyu would be hurled into the other. And ultimately the two realms would meet to engage in a terrible climacteric struggle. The lone protracted war between Good and Evil would come to a close in “The Affair.” Then for a season thick darkness would cover the face of the earth, and the whole universe would quake with the shock of the encounter. Fire and death would swirl over all, and there would be gnashing of teeth and dreadful wailing. The terror in the world would be “like the terror of the lamb when it is devoured by the wolf.” . . . But at last the fury would abate, and slowly, wearily, almost ready to perish because of the severity of the ordeal, Ahura Mazda would emerge — the victor. Then all the hills and mountains would melt and pour down over the earth, and all men would have to pass through the boiling lava. To the just and righteous, however that lava would be as warm milk; only to the wicked would it be scalding and fatal. The just and righteous would wade through it with laughter on their lips, rejoicing over a victory so well won. And the earth thereafter would be an everlasting Paradise wherein there would be no more mountains or deserts or wild £asts or savages. The Kingdom of Ahura Mazda [ p. 207 ] would have reached its consummation, and all would be well thenceforth forever and aye. . . .

¶ 3

SUCH, as best the scholars can make it out, was the religion which Zoroaster sought to bring to his fellow Iranians. Perhaps it was not so free of heathenisms, not merely so exalted and superbly spiritual, as the scholars have pictured it. Save on the basis of the miraculous, one finds it nigh impossible to explain the sprouting of so altogether fair a religion before the night of barbarism had yet quite lifted in Iran. But however much less noble it may have been than it is now pictured, [ p. 208 ] still it was far too noble for its time. Tradition declares that for ten harrowing years the appeal of Zoroaster was like a voice in the wilderness. None would give ear to the man, or, giving ear, coaid make him out Solitary and misunderstood he went about, harried by the heathen priests, imprisoned by heathen princes. More than once he cried out desperately to his God:

To what land shall I turn.

Or whither shall I go?

Far am I from kinsmen.

Distant from friends:

Foully am I dealt with by peasants and kings.

Unto Thee I cry, O Wise Spirit,

Unto Thee I cry, Give me Help!

He needed help, did poor Zoroaster, for his was no light task. It was a day when the conversion of a people could come only as a result of converting their prince — and princes were not willing to be converted. After ten long years of struggle, the outcome seemed altogether hopeless. When one winter’s night he was refused shelter even for his “two steeds shivering with cold,” a great temptation to surrender almost tore him from his faith. The Lie Demon — so goes the legend — took hold of Zoroaster and tried to shake him from his devotion. “Hold!” cried the Lie Demon. “Dare not > to destroy my handiwork! Remember, thou art the son of thy mother, and thy mother worshipped me. Renounce the right religion of Mazda, and obtain at last the favor of kings.” Fierce then waxed the struggle in the soul of the tired prophet; but in the end the truth [ p. 209 ] was victor. “No I” the prophet cried back to the Lie Demon. “I shall not renounce the right religion of Mazda — not though life and limb and soul be torn asunder!” …

And soon thereafter Zoroaster made his first convert. He was not a prince, however — merely one of his own cousins. Still, it was a start — enough of a start to keep the prophet at his task for two years more. And then at last a real prince was converted, a mighty ruler named Vishtasp who became the Constantine of the new faith. A church militant was formed, and holy wars were waged against the Turanian savages on the north. Those Turanians were wild bedouin raiders [ p. 210 ] who made the life of the Iranian farmers a nightmare, and they seemed to Zoroaster the personification of all Ahura Mazda hated. The prophet waged war without mercy against them. “I am he that tortureth the sinners,” he declared, “and he that avengeth the righteous. Though I bring bitter woe, still must I do that which Ahura Mazda declareth right.” Yet for all his unsparing zeal, Zoroaster seems not to have been narrow. “If even among the Turanians there arise those who help the settlements of Piety,” he declared, “behold even with them shall the Lord have his habitation.” According to tradition, one of Zoroaster’s most loyal and trusted followers was a Turanian named Fryana. . . .

Such was the gospel by which Zoroaster lived — and for which he died. For it may be that he did die in its ministry. Legend has it that Zoroaster was struck down while he stood ministering at an altar of fire, brought to book by one of those heathen priests whose worship he had routed. …

¶ 4

WE may not be quite certain as to just what was the teaching of Zoroaster himself; but there can be no doubt as to what it became at the hands of his successors. It degenerated. The faith voiced in those prophetic hymns called the Gathas was too nobly exacting, too exaltedly strenuous to last in its original purity. It was too bright for the weak eyes of ordinary men to gaze on steadily, too vast for their little hands to grasp. So very soon its brightness was dulled by the streaming breath of sedentary theologians, while its vastness was eaten [ p. 211 ] away by the attrition of greedy priests. In the beginning, Ahura Mazda may have been but a spirit, a dream, an ideal. He may have been little more than the name that stood for all that was good in the world, a conviction around which to build one’s life. But a later generation made Ahura Mazda the name of a person, a superhuman being with not a few crudely human attributes. Ormuzd, he was called. . . . And Angra Mainyu, the Lie Demon, the name that stood for all that was evil in the world, also became the name of a person. Ahriman, this person was later called, and he was then thought to be not merely the Agent of Evil, but its original creator. . . . The six spirits, Good Thought, Right Law, and the others, which Zoroaster had thought of as ties serving Mazda, became very personal angels, and increased in number from six to s i x t seventy, a thousand, ten thousand! And opposed to them were set many thousands of devils. . . . All the winning simplicity of [ p. 212 ] Zoroaster’s vague ideas was bit by bit destroyed by bedizening theologians.

But this elaboration of Zoroaster’s stark doctrine was not nearly so tragic as the perversion that ensued. The poetry and truth of Zoroaster became prose and error at the hands of those who came after him. If he said “be pure,” meaning clean with righteousness, straightway they imagined with their literal minds that he meant be ritually pure. Currency was given to the most extravagant notions of taboo and “defilement,” and to the absurdest rules for their removal. Certain things were declared to be “holy” and certain other things “unholy”; and ne’er the twain dared be brought together. That led of course, to all manner of complications. For instance, among the things considered “holy” were fire, water, and earth; while a corpse was thought to be dreadfully “unholy.” The disposal of the dead therefore became a serious problem. Since the corpse might not be buried or burnt, or drowned, there was nothing left but to expose it on a high “Tower of Silence,” where it could be devoured by the vultures. Elaborate precautions had to be taken lest a drop of rain touch the dead body, and funerals were permitted only on dry days. Professional bearers, who took the most scrupulous care to guard themselves against “defilement,” carried the corpse to the top of this tower. There it was left until the carrion birds had made an end of their ghoulish feast, and only after three days of exposure were the bleached bones cast into a pit. To this day the Parsees, the descendants of the old Zoroastrians, still dispose of their dead in that way. . . .

Not merely corpses, but all manner of other things [ p. 213 ] were considered taboo and “unclean.” So many indeed were they, and so difficult to think of, that success in the task of avoiding all “defilement” became practically hopeless. Therefore, in order to be on the safe side, it was forbidden that any religious task be essayed unless the celebrant first “purified” himself as though from an actual and definitely remembered “defilement.” Cow’s urine was considered the most potent “purifier” and those who desired to cleanse themselves ritually had to swab themselves with the stuff six times a day every third day, for nine days. They had to rub down one member after another with it, until finally the demon of “defilement” was driven all the way from the head to the feet. The point of exit for the demon was always the big toe of the left foot, and when ejected thence, it went off with a shriek to the north where all the demons — and once all the Turanians — dwelled. Every time a man touched a corpse, or a menstrual woman, or any other tabooed thing, he had to go through that revolting process of ritual purification all over again. That is still the law among orthodox Parsees. …

Now the growth of such a ritual law was almost as natural and inevitable as the growth of lichens on a rock. Only the great souls, the sages and prophets, have ever been able to find salvation in a religion naked of ceremonial adornment. Ordinary men even today are incapable of comprehending abstract ideas. Before a thought can become real to them it must be concretized and made obvious through symbols or symbolic action. That is why the career of every prophetically founded religion on earth has been a career of more or less progressive frustration. What happened in Jainism, [ p. 214 ] Buddhism, and Taoism happened also in Zoroastrianism. The prophet was succeeded by priests, by ordinary men of more than ordinary talent who attempted to “organize” the truth their master had uttered. And tragedy was then inevitable. In the first place, those priests were incapable of really comprehending their master’s truth. They were men of talent, not of genius; and talent is not enough for the full understanding of a great gospel. In the second place, even had they been able to grasp the prophet’s truth, they could not possibly have organized it. For truth, by its very nature, is incapable of being organized. It belongs genetically to the realm of the ideal, and it can no more be regimented than the rainbow can be hung with clothes. Consequently there was no avoiding frustration. The priests reached out to lay hold of Zoroaster’s truth, but their blunt fingers could close on falsehood. Eagerly they strained to light their at the brave little flame which he held up against dark swirling immensities of fear; but they succeeded only in getting their brands to smoke and crackle in shamed impotence.

[ p. 215 ]

But though the priests failed to preserve Zoroaster’s gospel they succeeded all too well in preserving themselves. Indeed, the more they failed with the one, the more they succeeded with the other. For the more they made salvation a prize that could be won only by strict observance of the ritual, the more they made themselves the donors of salvation. No doubt that was why the ritualization of the religion was carried to such inordinate lengths by the priests. It paid. It gave those priests enormous power over the populace, and enabled them to establish themselves as a permanent caste in Iran. They organized themselves into an hereditary order, and at one juncture even instituted a papacy in the land. They were called the Magi, and their fame as necromancers later spread through the world . [1] Their chief function was to officiate at the regular temple and household services. Masked with thick veils to keep their breath from polluting the holy flames, they served at the fire-altars five times each day. With like punctilio they served also at the haoma-altars which Zoroaster in his day had tried most strenuously to destroy. Haoma (called Soma in India), an intoxicating vegetable extract, was considered highly sacred among the primitive Aryans, and was used in the earliest religious rites. Evidently its hold on the masses was so firm that despite Zoroaster’s reform it was able to continue as a sacramental property. In the priestly law-books we find detailed accounts of just how the haoma rites were performed after the prophet died. Twigs of the sacred plant were pounded in a mortar; the heady juice [ p. 216 ] was mixed with milk and holy water; it was strained; and then it was swallowed by the priests. (A potent cocktail it must have made!) At one time it took eight priests to perform the rite, one to recite the Gathas, one to pound the haoma, one to mix the juice with the milk, four others to stand by and help, and one to watch over all!

But the haoma rites were not the only relics of the old heathenism that returned after Zoroaster’s death. Many of the old fallen gods, too, were dragged back into fashion — Mithra and Anahita and others. The very Gathas of Zoroaster were corrupted by interpolation, or at least misinterpretation, so that they might give the impression that the prophet himself had commanded the worship of those gods. . . . Mithra especially became popular; and as we have already seen, his cult later spread beyond the borders of Persia into Babylonia, Greece, and finally into Rome itself. For at least two centuries that cult struggled with Christianity for the dominance of the Roman Empire. And when in the end it was vanquished, its place was taken almost immediately by Manichaeism, a religion founded in the third century by the Persian prophet, Mani, who was crucified by the Magian priests as a heretic. …

¶ 5

BUT the importance of Zoroastrianism has always been qualitative rather than quantitative. Its highest significance lies in the influence it has exercised on the development of at least three other great religions. First, it made contributions to Judaism, for between 538 B. C. (when the Persians under Cyrus captured [ p. 217 ] Babylonia and set free the Jews exiled in that land) and 330 B. C. (when the Persian Empire was destroyed by Alexander) the Jews were directly under the suzerainty of the Zoroastrians. And it was from these suzerains that the Jews first learnt to believe in an Ahriman, a personal devil, whom they called in Hebrew, Satan. Possibly from them, too, the Jews first learnt to believe in a heaven and hell, and in a Judgment Day for each individual.

Zoroastrianism had developed quite fantastic ideas about the Judgment Day which the prophet had declared to be the consummation of all things. In the first place, his professed followers had grown a little tired of waiting for this universal “Affair” that Zoroaster had prophesied. They had begun to take more stock in an “affair” for each individual, a dread day of trial that was due immediately after death. The soul of each dead person, it came to be believed, was convoyed up to a fateful bridge and then commanded to march forward. If it was the soul of a righteous man, then the bridge opened up into a broad thoroughfare over which the soul marched straight on to the Heaven of Ormuzd. But if it was the soul of a wicked man, lo, the bridge contracted till it was as narrow as the edge of a sharp scimitar, and the guilty soul was sent hurtling down into the foul Hell of Ahriman. . . . And that naive idea was taken over into Judaism, which until then had known of nothing more than a vague “pit” called sheol, into which all souls at death were cast indiscriminately.

And the Zoroastrian picture of the ultimate “Affair” for all the universe also left its impress on Jewish think- ing. Scholars today are fairly agreed that most of the [ p. 218 ] Biblical and Apocryphal accounts of what would happen in “the end of days,” all the wild apocalypses from Daniel through and beyond Revelation, were inspired at least in part by Persian eschatology.

Through Judaism, the religion of Persia left its mark also on Christianity; and not merely through Judaism, but also through Mithraism. When we come to tell the story of the rise of Christianity we shall have to refer at some length to the many compromises with Mithraism which seem to have been made by the victorious faith.

Very directly, also, Zoroastrianism influenced the religion preached by Mohammed. Many ideas set down in the Koran reveal that influence; and even more of the ideas set down in later Moslem writings. . . .

And in our very own day we find a modernized form of Zoroaster’s faith being preached by Mr. H. G. Wells!

Only by virtue of this pervading influence of its ideas can Zoroastrianism be called a world religion today. Its nominal confessors are few, very few, in number. They were mercilessly persecuted and almost exterminated when the Mohammedans swept into Persia in the eighth century; and they have been persistently oppressed from that day on. Only about nine thousand of their posterity are left now in all the land!

But there is a significant colony of them in India, in all about ninety thousand Zoroastrians who dwell in and around Bombay. There they seem to be a veritable leaven in the whole population, and their importance is far out of proportion to their numbers. They are known there as the Parsees (really, the Persians), and their culture, honesty, and benevolence are bywords in [ p. 219 ] all India. Even their present multitudinous rules of ritual “purity” have failed to smother the fires of faith which Zoroaster lighted unnumbered centuries ago. The Parsees are still in their way servants of Ahura Mazda, warriors for Right in the battle which is life. A tiny minority, forever harassed and scorned, nevertheless they are today among the very noblest of mankind. . . .

By worldly standards, Zoroastrianism failed. It was so overwhelmed by Christianity and Mohammedanism that today it is the size of a forgotten denomination. But by truer standards, Zoroastrianism triumphed. It triumphed as have few other faiths on earth, for its fire, though often on the altars of strange gods, still illumines much of the world. . . .

¶ Notes

It is from their name. Magi (pronounced with the, “g” soft and the “i” long, as in “gibe”), that we get our words magic and magician. ↩︎