[ p. 303 ]

[ p. 304 ]

¶ BOOK EIGHT — WHAT HAPPENED IN ARRABIA

I. Mohammedanism

1: The idolatrous religion of primitive Arabia — Mecca and the Kaaba. 2: The story of Mohammed — his gospeL 3: The preaching of the gospel to the Meccans. 4t The preaching to the pilgrims. 5: The flight to Medina. 6: The Jews refuse to be converted — conflict with Mecca. 7: The military character of Islam — the Holy War. 8: The character of Mohammed — his compromises — the pagan elements in Islam. 9: The qualities in the religion.

[ p. 305 ]

AND now we are come to the founding of the latest—perhaps the last—of the great world religions: Islam. For the third time the Arabian Desert plays a major part in the history of our believing world. In that region’s giant womb there had already been conceived the Babylonian worship of Ishtar and the Hebrew worship of Yahveh. Now, more than two thousand years after the birth of that second child, the desert conceived and brought forth yet a third: the Mohammedan worship of Allah.

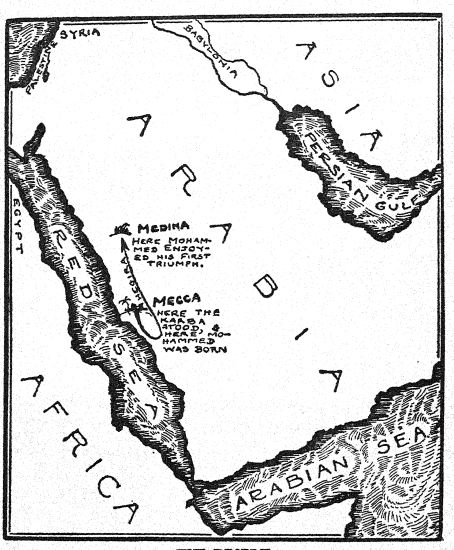

The religion of the Arabian Desert in the sixth century A. D. was much what it had been a thousand or even two thousand years earlier. Changes come rarely in the desert, for rarely are its denizens able to remain in any one place long enough to advance or even decay. Therefore, long centuries after the East had gone Buddhist and the West had gone Christian, Arabia, that vast wasteland pinched between East and West, still remained crudely animist. Each bedouin tribe worshipped its own tribal fetishes, rocks and trees and stars; and the only approximation to a national cult among them was a general [ p. 306 ] awe of a particular fetish resting in the city of Mecca, This fetish, a black rock enshrined in a small square temple called the Kaaba, was thought to be possessed of dreadful potency. An energetic priesthood arose in Mecca, and perhaps it was largely responsible for the national reputation enjoyed by that fetish. Perhaps, too, that priesthood was largely responsible for the national custom of making pilgrimages to Mecca. From every end of the desert the tribesmen were wont to straggle down to Mecca during one season of the year, in order to prostrate themselves before the Kaaba. And just as the merchants of a modern city arrange for minimum exactions by the railway men for all those coming to a convention in their midst, so the priests of ancient Mecca arranged for minimum hazards from highwaymen for all those on pilgrimage to the Kaaba. Somehow they forced the whole land to recognize and respect a solemn taboo against waylaying pilgrims. During four months in the year the open desert, where every shepherd clan was also a robber band, became as safe as a walled city to all who were on their way to Mecca. And as a result, Mecca became not merely the religious center, but also the great market-place of Arabia. In a land where wealth was almost nonexistent, and authority seemed scattered beyond hope of concentration, Mecca somehow managed to become rich and unchallengeably powerful,

¶ 2

NOW in about the year 570 A. D. there was born in this city a child to whom was given the name Ubu’lKassim. In later years he came to be called Mohammed, [ p. 307 ] the “Praised One,” just as Gautama came to be called Buddha, the “Enlightened One,” and Jesus came to be called Christ, the “Anointed One.” But to Ubu’lKassim in his early years was accorded very little praise. Although he was of the priestly caste, he belonged — like Jeremiah in Israel, and perhaps Zoroaster in Iran — to a branch of the caste that had been crowded and elbowed out of power. (Cynical historians find in that circumstance the major reason why Jeremiah and Zoroaster and Mohammed ever attacked the ruling priesthoods in their lands.) The lad was orphaned while still young, and because his immediate relatives were for the most part poor, he soon had to shift for himself. He became a camel-driver, and went off with trading caravans as far as Syria and perhaps even to Egypt. He was grossly untutored, of course, and probably could neither read nor write. But he was quick-witted and had an insatiably inquisitive mind. Unlike the other Arab camel-boys, his eyes were wide open to the wonders of the strange lands he visited, and his ears were pricked up to catch all that was being said in the foreign marketplaces. Especially was he inquisitive on the subject of the religions in those far away places, for he seems to have been innately of a religious temperament. We are told he was given to spells of melancholy and to occasional fits of what may have been epilepsy. (So many of the greatest religious leaders in history are said to have been epileptics or otherwise neurotic, that psychologists are inclined to believe religious genius is somehow a result of a disease of the mind. But that is no reflection on religion, for every other form of genius seems [ p. 308 ] also a product of a disease of the mind—as the pearl is a product of a disease in the oyster. . . . )

We have no undisputable data concerning the early life of Mohammed. All we know with any certainty is that, after years of travel with the caravans, he managed to better his lot by finding favor in the eyes of his em- plOyer. She was a rich widow named Khadija, and the good-looking young man with the large head and beautiful black beard so attracted her that finally she [ p. 309 ] decided to marry him. She was already forty, and he only twenty -five; but he appears to have acquiesced with alacrity. Khadija was a woman of high character and understanding, and quite probably Mohammed loved her… (He remained true to her until the day of her death.) And certainly he must have been grateful to her, for in a day she lifted him from the low station of a camel-boy to high place as a rich and respected Meccan trader.

Relieved of the necessity of earning his livelihood, Mohammed now began to indulge his contemplative nature. We are told that he went off into the desert again and again to commune there with his soul. The humdrum life of a rich fruit-and-produce merchant did not satisfy him. It was comfortable and yet not comforting; it could keep him occupied, but not satisfied. Like every other great soul, he was not content with the knowledge merely of how to keep alive: he wanted to know why. And seeking that higher knowledge, groping in a great fury and pain for that ultimate blessedness which is called salvation, he finally fought his way through to the idea of Islam. It came to him with overwhelming conviction that there could be but one way out of the confusion which was life: through submission to God. Not to any little venomous god pent up in a rock or a tree; not to any one of those low djinns or spirits which his fear-harried brethren tried to bribe with blood and frenzied praise. No, to the One Great God who must be in and over all the earth!

The patron deity of his own particular tribe was known as Allah, and, for want of a better name, Mohammed instinctively gave that one to his new God of [ p. 310 ] the Universe. But he was not blind to the fact that other peoples knew Him by other names. He realized that this Allah whom he had just come to know a been known to the rest of the world for centuries. re prophets as ancient as Abraham and as recent as Je us had proclaimed this God to the peoples beyond _ the desert. Indeed, every great city had had its prophet of this One God— every great city save Mecca. Mecca alone was still foul with idol-worship; Mecca alone knew the One Allah. And as Mohammed wandered there in the loneliness of the desert, brooding over that evil, it seemed to him that at last it must come even Mecca’s turn be saved. Even more: the conviction took hold of him that he must be its savior. He, Ubu’l-Kassim of the tribe of Koreish, he who had risen from squalor to be spouse of the wealthiest woman m Mecca he must be Allah’s Apostle to Mecca. Many prophets had come before him, and right nobly had they sought to bring a measure of the knowledge of Allah to the world. Bu only with him could there come to mankind the final knowledge of the One God. For he, Ubu’l-Kassim, was none other than the “seal of the prophets!”

Such was the conviction that somehow began to take hold of that queer and moody fruit-and-produce merchant of Mecca. When he came to tell of it in later years, he declared the conviction had come to him m a sudden revelation. He insisted that it had come to him miraculously in a vision. Perhaps that was. true. Being one of that strange band of great religionists—the band that includes Buddha, Zoroaster, Jesus, and almost every other great prophet of history—he was subject to those psychic storms that do yield “visions.”

[ p. 311 ]

But one cannot doubt that the sudden revelation came to him, as it did to every one of the others, only after a long evolution of inward disturbance and uncertainty. One can see quite clearly in Mohammed’s conviction the [ p. 312 ] result of much pondering on the religious notions of the * Jews and Christians and Zoroastrians he had met in the market-places of Syria. In the hidden recesses of Mohammed’s being, the idea of Allah, the One God, must have been welling up for years before at last it flooded over the threshold and so imperiously revealed itself to his conscious mind.

¶ 3

BUT from that day forth, Ubu 1-K.assim, the indolent, dreamy husband of the rich Khadija, showed himself to all the world a changed man. No longer did he seem melancholy and lost. He had found himself. He had a purpose now: to win idolatrous Mecca to the worship of the Omnipotent Allah.

But he was no reckless fool. He realized that to announce himself at once to the whole city as its savior would bring him only jeers or worse. So he confided his secret first to his wife, and she, perhaps to his amazement, neither laughed nor scolded. On the contrary, she firmly believed him when he said he had been visited by Allah in a splendid vision and had been appointed the Prophet of Mecca. And fortified by her confidence, he then whispered his tale to others. He still acted discreetly, however, and approached only his closest friends and relatives. And somehow they, too, were impressed. They accepted his amazing tale as true, and secretly convinced others of it, who in turn convinced still others. And thus the movement began to spread throughout the town. Everything was done with the greatest secrecy, for it was realized that if the rulers of the city discovered what was on foot, little mercy would be shown to [ p. 313 ] Mohammed. He would be regarded as the ringleader in a political conspiracy, as one who sought to overthrow the priests of the Kaaba and rule in their stead; and he would be treated accordingly. So the process of winning converts had at first to be carried on with the sharpest caution.

But a day came at last when Mohammed’s following seemed strong enough for him to dare take his life in his hands and announce himself. Immediately there ensued a tumult in the city, and a great fury of debating and strife. The ruling oligarchy was thrown almost into a panic, for when at last Mohammed announced himself as the prophet, his following was already too large to be crushed out summarily. Diplomatic over.tures were made to the pretender (for so he was considered by the rulers) ; but he refused to bargain. And then less conciliatory means were resorted to.

Unhappily for the rulers, they could not resort to the assassination of Mohammed as a means of putting a swift end to the insurrection. Mecca was a holy city, and there was a dread taboo against the shedding of any blood within its precincts. The person of Mohammed could therefore not be touched, and the only possible way left of stamping out his rebel movement seemed to be by a systematic boycott of his followers. This was soon begun, and it brought bitter suffering to the poorer of Mohammed’s supporters. But it utterly failed to check the movement. It only aroused an enthusiasm and a fervor in those devotees of Mohammed that seemed able to withstand any privations. Finally, therefore, the frustrated rulers were driven to a declaration of open war. They drove Mohammed and his abettors [ p. 314 ] into one quarter of the city and blockaded them there. (The taboo against shedding blood did not prohibit the slaughter of people by starvation.) For months the Mohammedans were held prisoners in their houses, until finally, -starved to despair, they surrendered, Mohammed, who throughout the siege had been having new revelations from Allah, now suddenly announced that the One God had assured him it was no sin to worship the Meccan djinns and spirits. And with that capitulation to the idolatry fostered by the priestly oligarchy, the blockade was raised and the erstwhile rebels were allowed to go free.

But almost immediately Mohammed repented. Remorse overcame him at his cowardly defection, and he cried out that he had sinned. He declared a new revelation had come to him and made it plain that the previous one had been a whisper from the devil. (Mohammed had taken over as part of his religion the Persian belief in a wicked Ahriman.) There was, after all, to be no worship of the Meccan goddesses and spirits, for Allah forbade it. In the camp of His true followers there was room for the worship only of Allah! . . .

And then persecution began anew.

¶ 4

BUT this time Mohammed did not remain in the city and try to hold out against his enemies. He knew he was not equal to it. His first and dearest believer, his wife Khadija, had just died; and he was left a dejected and broken man. He could not possibly continue facing the unrelenting persecution by his enemies — so he fled. He stole off to the neighboring oasis of Taif, and tried [ p. 315 ] to gather new converts there. But he failed dismally, and finally he was reduced to entering a plea for permission to come back to Mecca. The rulers were willing to grant it, but on condition that Mohammed altogether refrain from ever again stirring up dissension among the Meccans. And only on his acceptance of that humiliating condition was the hapless prophet allowed to drag his way back to Mecca.

But though fallen so low, the prophet soon began to try to rise again. Almost from the moment he returned, Mohammed began once more to preach his iconoclastic doctrine. He was careful, however, to keep the letter of the agreement which bound him scrupulously to avoid preaching to the Meccans themselves. Only the strangers in the city, the traders and pilgrims and bedouins encamped for the night, did Mohammed approach with his gospel. And not infrequently these strangers would hearken to him eagerly, for many were the Arabs who were ready for his ideas. For centuries there had been many tribes of Jews living in the desert. For centuries, too, there had been strings of Christian traders wandering along all the caravan routes. And from these Jews and Christians the whole land of Arabia had heard tell of the One God. So when Mohammed sat there cross-legged in the bazaars of Mecca, and held forth to the strangers gathered in a silent circle about him, he uttered religious sentiments for which they were already well prepared.

One pictures him there, that good-looking Arab prophet, amid all the traffic and din and stench of that Oriental market-place, seated in the half-light of a shadowed court and talking, talking, talking of his [ p. 316 ] Allah. He talked well; his speech was rich with that glowing imagery so dear to the heart of the Oriental. He told many tales which he said had been revealed to him by Allah, but which actually were only garbled versions of the Biblical stories he had heard from the lips of Jews and Christians in his youth. He told of Ibrahim, the first of the prophets, and of Ishmael his son, the founder of Mecca. He discoursed also on Suleiman, the great king, and on Jesus, who had been born in a manger. And the eyes of his auditors twinkled with delight in the dimness of the courtyard. … Or he told of the paradise which all true believers would inherit, and the eyes of the listeners gleamed with eagerness; or of the devil’s hell, and their eyes fairly popped with fright. …

At death, said this prophet, the soul of the believer [ p. 317 ] was lifted gently out of the body, and was convoyed up above by “a driver and a witness.” To it was shown a ledger of reckoning wherein two angels had set down all its deeds on earth. Even though the fate of each man hung around his neck from the beginning, still was each man’s soul held to a reckoning after death. He who had been pious on earth was translated to a garden of bliss after death; and there, clad in robes of shimmering green silk, he lolled forever on green-cushioned divans. (How like a desert Arab, to paint paradise a place that is green!) Fruit and forgiveness did the pious man enjoy in Paradise, gorging himself on ripe bananas that ne’er caused aching belly, and quaffing whole flagons of wine that ne’er caused aching head. Maidens of surpassing beauty, large-eyed and well-rounded of hip — but modest withal, and “restraining their looks”— served him there and brought him comfort. And thus did the pious man delight in his reward, living in Paradise without labor or care, without want or fear of want, throughout all the endless ages! . . .

But he who was a sinner, he who “believed not in Allah nor fed the poor” — he fared far otherwise. On his death his soul was torn violently from his body. Down into Hell that soul was hurled, there to wear a cloak of fire and drink scalding water and pus. With maces was the sinner beaten in Hell, until he begged piteously for release. But there was no release for him. No mercy could be shown him, nor could his torture cease, until at last the final Judgment Day arrived. But when that day did come, lo, he would be annihilated utterly! Not even his soul would remain existent. And the pious in Paradise would then be brought back to [ p. 318 ] earth, and on a paradisiac earth they would revel in bliss forevermore! …

Thus would the prophet talk on with solemn mien to those who sat about him. And when one of them, shaking off the spell of the speaker’s words, would ask in a sco ffin g tone: “Huh! Shall I, though reduced to dry bones, become alive again?” — then would the prophet give answer with a grim smile: “If thou dost doubt it, wait till the Judgment Day comes, and then thou wilt find out!”

So would Mohammed labor with the strangers from far away places. And when those strangers went back to their homes, glowing reports of the strange prophet would go back with them. The fame of Ubu’l-Kassim spread. Throughout the length and breadth of the desert, people began to talk wonderingly of the Prophet of Allah who dwelt in Mecca.

¶ 5

NOW on the main caravan route north from Mecca there was a settlement called Yathrib which from of old had been a rival of the capital. And the elders of Yathrib, hearing of Mohammed and of his persecution at the hands of the elders of Mecca, sent secret emissaries to him, entreating him to take refuge in their midst They even offered to make him the ruling sheikh of their city if he would come. And Mohammed did not reject their overtures. Perhaps he had begun to despair of ever attaining his end by “boring from within” the city of Mecca. He may have begun to wonder whether he could not accomplish more by “kicking from without” So he sent his own emissaries back to Yathrib [ p. 319 ] with word that he would come — on condition, however, that the men of Yathrib were willing to join him in a holy war to make Allah the god of all Arabia.

But before the negotiations could be finally concluded, a rumor of what was on foot reached the ears of the rulers of Mecca. They saw immediately that it would not do to temporize any longer. Mohammed was too dangerous a man to allow around, and, taboo or no taboo, he had to be destroyed. But, in order to distribute the guilt, the ruling clans agreed to share equally in the crime. Each appointed one of its members to serve on an assassination committee, and on the night of the sixteenth of July, in the year 622, the committee broke into Mohammed’s sleeping chamber to strike him dead. But when they rushed at the couch, behold, Mohammed was not there! His cousin Ali was lying in his place, and the prophet was nowhere in sight. Apprised of the plot, he had already escaped from the city long hours before the assassins set out for his house. And although the Meccans sent their fleetest camel-men to pursue after him on the road to Yathrib, they could not overtake him. Mohammed had guessed they would pursue him on the road north, and had gone south instead. With only Abu Bekr, his most trusted disciple, he stole away and hid in a cave far south in the desert. And there he lurked in trepidation many days. Abu Bekr was frankly terrified. “Behold, we are but two against a whole multitude,” he complained. But straightway Mahomet answered, “Nay, not two, but three — for Allah is with us!”

But for all that he was so sure that Allah was with him, Mohammed took no chances. Only after weeks [ p. 320 ] of hiding did he and his friend venture out into the open and begin to make their way north. For weeks they crawled furtively through the desert, until finally on Friday, the twentieth of September, they reached their goal. At last they were safe in Yathrib.

¶ 6

WITH that flight, the hejira as it is called in Arabic, the Mohammedan era begins. (To this day the Moslems date all records from the time of that Hejira, as all Christians date them from the supposed time of the birth of Jesus — and all chroniclers of the village of Hamlin date them from the supposed time of the coming of the Pied Piper.) Once in Yathrib, the prophet immediately set out to convert all who were in sight; and to a degree he was successful. But there was one element in the population that stubbornly refused to be won over. There were in Yathrib several tribes of Jews that had lived in that region almost from the time when the Romans drove them out of their own home in Judea. They were by now hard to distinguish from the Arab tribes, differing from them, indeed, only in religion. Despite more than five centuries of life in pagan Arabia, these Jews still worshipped their One God and prayed for their Messiah to come. When rumor first reached them of a prophet who was being hounded out of Mecca for preaching the idea of a One God, they of course were interested. In a moment of wild hopefulness they even wondered if that prophet might not really be their long-awaited Messiah. And when Mohammed arrived in Yathrib he made every effort to encourage that impression. Revelations of a pro-Jewish [ p. 321 ] nature now came to him thick and fast. He commanded his followers to turn as did the Jews toward Jerusalem when they prayed. He forbade them to eat pork or the meat of any animal that had not been ritually slaughtered; and he appointed the Jewish Day of Atonement the great holy day of the year. He even changed the name of his One God from Allah to Rachman — the “Merciful.” Out of all his following he chose a Jew to be his scribe to set down his revelations in the book that later came to be called the Koran. . . . But despite all these concessions, the Jews as a body refused to come over into his camp. The moment they discovered his ignorance of the Holy Law and the Prophets, and his by now notorious weakness for women, they began to scoff at his pretensions. Their poets wrote satirical ballads against him, and their elders refused to take him seriously.

And thereupon Mohammed made a complete aboutface. Realizing with chagrin that there was nothing to be hoped for from the Jews, he brought all his proselyting energies once more to bear on his own people. Fresh revelations now came to him reversing the earlier ones, and declaring that the true direction of the worshipper in prayer was toward Mecca, not Jerusalem, and that the great annual holy season was the old Arab Festival of Ramadhan, not the Jewish Day of Atonement. And with such concessions to the ancient paganism, the winning of converts from among the Arabs in and around Yathrib increased rapidly.

But material problems began to trouble the prophet. His property in Mecca had been confiscated after his flight, and what wealth he had brought with him had [ p. 322 ] dwindled away in Yathrib because of bad investments. To add to his difficulties, scores of believers who had fled after him from Mecca were now wandering about in Yathrib without employment. It was clear, therefore, that some means of providing for himself and his followers had to be found, and found immediately. So Mohammed gathered his followers together and sent them out to waylay caravans from Mecca. For almost a year he sent them out on such expeditions, until finally he saw that even highway robbery, when practiced according to the rules, was unprofitable. He was then forced, therefore, to practice the profession with no respect for the rules. The Meccan caravans were too well armed during most of the year to be held up successfully. Only during the pilgrim season, when they were protected by that ancient inviolate taboo, did the caravans dare to sally forth unarmed. So now, in desperation, Mohammed actually decided to stage attacks on them during that season.

Such tactics amounted to an almost unprecedented outrage, and only by a stratagem could the prophet manage to inveigle his followers into committing the first treacherous holdup. But once the deed was done, and the reward seemed to be not death but enormous booty, his followers — and most of the other Yathribites too — were quite willing to repeat the outrage. The Meccans leapt to arms immediately, however, for they realized that this thing put into jeopardy their whole future as the masters of Arabia’s commerce. They sent out a whole army, and fierce battle was joined with the Yathribites. Mohammed did not fight in person in the battle. He seems to have been physically a rather weak [ p. 323 ] man; even the sight of hlood made him sick. Tradition declares that he hid afar off, and kept his swiftest camels in readiness lest his men be defeated and flight become necessary. Even then he fainted soon after the battle began. . . . But when the battle was over, and the Yathribites emerged the victors, Mohammed came riding back into the city like a conquering hero. Substantially he was indeed the hero, for it was because of his astuteness as a tactician in planning the battle that his army won.

Mohammed was now the unchallenged master of the town, and its name was changed appropriately enough from Yathrib to Medina, “The City (of the Prophet) .” He no longer troubled to try to win the unconverted by suasion. Instead he ruthlessly put them to the sword. Gone was the gentleness that had marked his preaching in the former days. Gone was his old confidence in the power of abstract truth. In Mecca he had declared, “We hurl the truth against the falsehood, and truth crashes into it so that falsehood vanishes.” But now he hurled armies instead. “When ye meet those who misbelieve,” he now declared, “strike off their heads or hold them for ransom I” …

¶ 7

THE war with Mecca continued to rage, but in the end the Meccans were compelled to cry quits. Mohammed obtained consent to return as the virtual dictator of the city where but a few years earlier he had been a hunted criminal. And then he entered on a great holy war to win all Arabia to his cause. Armies were [ p. 324 ] sent north and others south to convert or slay in the name of Allah. And because the Byzantines and the Persians owned vast tracts of the desert in the north, Mohammed finally felt compelled to pit himself against them too. Nor did his ventures turn out unsuccessful even against such hosts. Somehow he could whip his followers into a frenzy of courage and recklessness. The Arabs had always loved violence, and he made violence holy for them. Mohammed assured them that to die fighting for Allah meant certain and immediate translation to Allah’s Paradise, There was but one way to prove complete faithfulness, he declared, and that was by complete resignation to the will of Allah. Islam, which may be translated “submission.” he made the watchword and the name of his faith.

Mohammed’s whole movement thus took on the ’ character of a religious militarism. Islam was the army [ p. 325 ] of Allah, and prayer was made a discipline quite like drill-duty in a modern army. To this day a bystander thinks of a sentry sounding the alarm when he hears the muezzin uttering the call to prayer from his lofty minaret. An observer thinks of soldiers “forming fours” and “presenting arms,” when he sees the Moslems drawn up in ranks in their mosques and praying and prostrating themselves with almost mechanical precision. Actually the Moslems do form a religious army to this day. Mohammed welded them into such a body almost twelve hundred years ago. “If you help Allah, lo, Allah will surely help you I” he cried to his followers. And because the help Allah seemed to exact was just the sort the warlike Arabs had ever loved to give, they helped with irrepressible zest. In the name of Allah and His Prophet, the army of Islam began to wage a Holy War that almost conquered the world! . . .

Mohammed only lived to see that war begin. In the year 632, just ten years after the Hejira, the prophet died. But he had lived long enough to set a movement on foot that has not halted to this day. Within twentyfive years after his death, his followers had already become masters not alone of Arabia, but also of Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Babylonia, and Persia. Within a seventy-five years they had conquered all the northern coast of Africa and almost all of Spain. Another decade, and they were marching up into the interior of France. And today, twelve hundred years afterward, Islam, the religion founded by that amazing fruit-andproduce merchant who saw visions in Mecca, stands next to Christianity as the most flourishing religion in the world. In twenty years, and without royal patronage, [ p. 326 ] there was created in the heart of darkest Arabia a religion which today numbers well over two hundred million adherents! . . .

¶ 8

TO follow the Arabs on their great invasions and trace the tremendous influence exerted by them in Europe, Asia, and Africa, would lead us far from the main purpose of this book. Europe owed to those invasions its awakening from that stupor which was the Dark Ages; and even Persia and India, along with Africa, were vitalized and advanced by them, too. It was the last (or was it only the latest?) plunge of the desertfolk out into the Fertile Crescent; and though it drowned the Crescent and half the rest of the world in blood, it also brought forth a blossoming of civilization almost unprecedented in history.

Islam, one must remember, is a great and wondrous religion. Even in Mohammed’s day it was, relatively at least, a high and noble faith. Few non-Moslems seem to realize this. They remember only the petty vices and crimes of the prophet of Mecca, and forget entirely his indubitable religious genius. They remember only the flagrant compromises, the arrant opportunism, the almost blatant charlatanry, that marked his career after the Hejira. And, especially if they are Christians, they love to mull over reports of the inordinate interest Mohammed evinced in women in his later years. Christianity has always looked on sex as in some way indecent and 'sinful; and for that reason most Christians cannot possibly associate a truly religious nature with an unsuppressed libido. But that is no more than a prejudice. [ p. 327 ] Mohammed, despite his fondness for his harem, might have remained to his dying day a man of the noblest prophetic character.

He did not remain that, of course. It cannot be gainsaid that, after the Hejira and his first taste of triumph, the exalted prophet in Mohammed gave way to the greedy, ambitious, unscrupulous priest. The “organizer” in him triumphed. From then on he was no longer the daring iconoclast, the receiver of “revelations” which, even if not miraculously inspired, seemed at least spontaneous and sincere. After the Hejira the “revelations” are quite blatantly premeditated forgeries. They are long editorials circulated in the name of Allah to save the seamy face of the prophet. In the days when Mohammed was suffered to talk only to strangers as he wandered about in the bazaars of Mecca his doctrine had been superbly ethical in character. “Blessed are they,” he then declared, “who are blameless as respects women, who are charitable, who talk not vainly, who are humble, who observe their pledges and covenants, and who guard their prayers; for they shall inherit Paradise.” The liquor of triumph had not yet gone to his head; it had not yet even touched his lips. And he had been still a kindly, earnest teacher of love. “Paradise,” he had then declared, “is prepared for those who expend in alms, who repress their rage, and pardon men. For Allah loves the kind.” “To endure and to pardon is the wisdom of life.” Or again: “Let no man treat his neighbor as he himself would dislike to be treated.” Or still again: “Let us be like trees that yield their fruit to those who throw stones at them.”

Nor was there aught of the ritualist in Mohammed [ p. 328 ] then. When a man came and said to the prophet: “Behold, my mother has died; what shall I do for the good of her soul?” — Mohammed answered: “Dig a well, that the thirsty may have water to drink! . . . The exigencies of empire-building had not yet arisen to demand a vast army bound by a rigid discipline of prayer and almsgiving. “One hour of justice,” he had then said, “is worth more than seventy years of prayer.” And: “Every good act is charity: bringing water to the thirsty, removing stones and thorns from the road, even smiling in thy brother’s face.”

Nor, finally, had there been anything of the doctrinaire in him then. When confronted by those who told him to his face that they did not believe his words, his only response had been the challenge: “Bring ye then a better revelation, and I shall follow it.”

But once success began to come to him, the worst in his nature revealed itself. His personal life became sordid, and his spiritual integrity was sapped. His craving for increase of dominion led him to reduce his standards until the mere recital of a formula — La illah il’allah, Muhammad, rasoul allahi, “There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is the Prophet of Allah” — that and the paying of a tax, were enough to make one a convert. Later even the formula was overlooked, and only the tax was insisted upon. On occasion Mohammed even resorted to buying converts!

[ p. 329 ]

As a result, the very paganism which Islam had set out to destroy began to destroy Islam. The idolatrous practice of the hajj, the pilgrimage to the Kaaba, was made one of the dominant elements in the religion. To this day it is counted of major importance. Even now [ p. 330 ] the Moslem pilgrims from every end of the earth can be seen dragging their way on foot or by camel to Mecca. Two hundred thousand of them brave the dangers of the desert each year in order to come to the holy city. At five miles distance from it they halt, wash, pray, put on clean seamless gowns, and then proceed bare-headed and barefoot to the holy shrine. They reverently kiss the black stone, solemnly go around the Kaaba three times running and four times walking, run to a neighboring holy hill seven times, run to a second holy hill, and then stop to catch their breath while they listen to a sermon. Finally they spend the night on the holy Mount Muzdalifa nearby, and after throwing missiles at three unholy rocks in the valley below, they go back to their homes in far Tunis or Bombay or perhaps Samarkand, and are at peace. They have performed the hajj, the pilgrimage, the holy act that earns them the right to wear verdant sashes around their fezzes, in token of the verdant Paradise they will surely inherit when they die. . . .

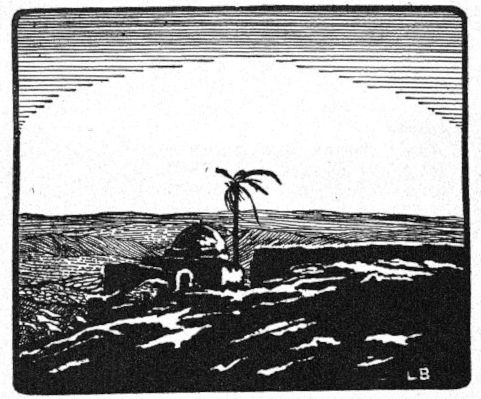

But the old idolatry against which Mohammed inveighed in his early ministry has returned in more than the hajj. Just as Mohammed himself accepted the Kaaba, so his followers accepted the lesser idolatrous shrines scattered throughout the desert. Of course the surrender was not made openly. Exactly as in Catholic Christendom, the local djinns and goddesses were made over into Mohammedan saints. To this day throughout the Moslem lands those little shrines can be seen nestling amid the hills or in the oases. Nominally they are memorials to old holy men; but actually they are often memorials to far older djinns.

[ p. 331 ]

The inundation of Islam by these returning tides of paganism began long before Mohammed died, and the further Islam’s shores extended, the more sweeping became that flood. In India the Moslem faith took over many of the characteristics of Hinduism. It became mystical and ascetic, inducing thousands of souk to rente and seek communion with Allah m the dep hs of to Indian jungles. It also took over many of the Hindu superstitions. The rosary, for instance, which was an emblem of the Indian god, Shiva, was made a ceremonial object in Islam. Ninety-nine heads were strung on a [ p. 332 ] cord, and each bead was made to represent one of the ninety-nine names of Allah. (It was not long before the Moslem theologians had succeeded in inventing ninety-nine names for the Unnamable.) To this day the pious Moslem tells his beads each day, “keeping his tongue moist” — and his fingers nimble — in the remembrance of Allah.

Islam, like every other healthy religion, has been in a state of incessant flux. Long centuries ago it grew to be as unlike the simple and homogeneous creed of Mohammed as Christianity became unlike the creed of Paul. In many lands it contrived to advance, became richer in emotion, deeper in intelligence, and nobler in spirit. In certain other lands it decayed and degenerated, becoming crude and animistic. Like Christianity, Islam was from the first an elastic faith, accommodating itself generously to the culture of each land which it sought to conquer. Necessarily, therefore, it was many times rent by schisms, and today there are some seventy-two sects in it. The largest of the unorthodox groups, the Shiite sect in Persia, broke away in defense of the issue that Mohammed’s son-in-law, Ali, was a veritable Imam, or divine incarnation almost like the Prophet himself. Out of the Shiite came in turn the Sufi sect, which maintained that Ali was only the first of a long line of such Imams, and that even ordinary men could become almost divine by a process of asceticism and mysticism. But most of the other sects are small and obscure, and arose out of piddling metaphysical or political differences. And between many of these sects there has been a rivalry and an animosity almost — but never quite — as bitter as that between the sects in Christianity.

[ p. 333 ]

¶ 9

Yet, for all the paganism and bigotry that still loom large in the religion of Islam, it remains nevertheless a great and wondrous faith. It has been one of the most fffectiv. civilizing forces in the history of Afnca aud Asia, and in a measnre also in that of Europe In Arabia Zli it accomplished a social revolution It condemned die common practice of infanticide in the case of girk restricted the dealing in slaves, opposed gambling and tonkenness, and almost put an end to the devastating Sbal feuds. And, incredible as it may sound, it also Sought about a marked improvement in &e condition of the desert women. Limitless polygamy had been the unquestioned law in Arabia from the time the prehistoric and perhaps mythical matnarchate came to an end Not until Mohammed came was that P r ^ cticc stricted so that a man might have no more than four wives at a time. . . .

But these social ameliorations were after all the lesser gifts of Islam. They were precious to those who profited hy them, but hardly of any considerable worldsignificance. The supreme gift of Islam was the ideal of unity which it somehow drilled into the heads of a hundred races— not merely the unity of God, but even more the unity of mankind. And preaching that ideal, commanding submission to the Oneness of the Umverse as the highest of all virtues, it revolutionized life for millions of fearful souls. It robbed them of the terror which aloneness had previously brought to them It gave them strength and a feeling of security, telling them thev were each a part of a vast and invincible [ p. 334 ] Whole. Every true believer was a soldier in an army, an international — and some day, pray Allah, universal — army that could not possibly fail to be victorious in the end. So what was there to fear? Life? It was fixed and settled for the true believer. All he had to do was live according to that manual-at-arms which is the Koran. He had merely to pray punctiliously, eat ritually, provide alms regularly, and give himself to the spreading of the name of Allah — and his reward was certain. The way of life for him was fixed, and its reason and justification, too. He had but to submit and accept his kismet, his fate, lashing his body and soul to that Rock of Ages which is Allah — and Paradise was certain. . . .

Every other great religion taught more or less the same doctrine, but none with such fierceness and unrestraint. Islam excluded no man from the army of Allah, magnifying the requirements until they could attract even the most advanced of civilized men, and minifying them so that they could appeal even to the most degraded of savages. And that is why to this day Islam can still win converts with twice the ease of any other religion. That is why to this day Islam is one of the mightiest institutions on earth for the ordering and beautifying of life in at least the “backward” lands. . . .