[ p. 276 ]

AND then something happened. Of a sudden — at least, so it seemed to those who had not marked the mounting of its steady ground swell— that little Nazarene sect, so long but an eddy unfelt even in tiny Judea, became a high sea that broke and rolled across the whole Roman Empire. A veritable tidal wave it became, [ p. 277 ] sweeping over one lend after another until finally it had inundated the whole face of the West and half the face of the East. To explain how that could have happened, one must remember what was going on just then in the Roman Empire. A great hunger was gnawing at its vitals, a desperate hunger for salvation. The whole Roman world seemed to be writhing in the throes of death, and fear of that death drove it to a frantic and panicky clutching after any and every chance of life. As a result, the mysteries, those secret cults which whipped men into mad orgies of hopefulness, flourished everywhere.

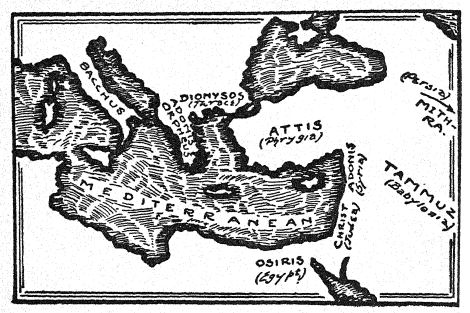

We have already dealt at some length in this volume with those mysteries of Greece and Rome. In origin, they were largely Oriental, and in essence they grew out of the belief that by certain magic rites a man could take on the nature of an immortal god. In most instances that god was portrayed as a young hero who had been murdered treacherously and then miraculously brought to life again. That same legend was told — with variations, of course — concerning Dionysus, Osiris, Orpheus, Attis, Adonis, and heaven knows how many other such gods. Arising out of the common desire for an explanation of the annual death and rebirth of vegetation, that legend was common to many parts of the world, and was believed during unnumbered centuries. It became the basis of a dozen different religions, providing all of them with the root-dogma that by means of sacrifices, spells, prayers, trances, or other such devices, mortal man could become immortal. By the first century of this era, the legend had spread to every civilized province in the Roman Empire — save, of course, that stubbornly resisting little province of Judea — and had everywhere made the people drunk with the heady liquor of its mystery salvation.

[ p. 278 ]

And side by side with these religious cults flourishing among the lower elements in the population of the Empire, different schools of philosophic thought flourished among the more learned folk. One of these was the philosophy developed in the city of Alexandria by an Egyptian Jew named Philo. According to this philosophy, God, the Father of All, was too vast to have direct contact with the earth, and therefore manifested himself only through an intermediary called the Logos, the “Word?” This Logos, which was sometimes called the “Son of God” or the “Holy Ghost,” had created the earth, and was the sole mediator between it and heaven. Man’s only approach to the Father, therefore, was [ p. 279 ] through this Logos, this “Son”; man’s only chance of entering heaven was by letting the “Spirit” flood his soul. Man could find a way out for himself, only by losing himself in the “Holy Ghost.” . . .

¶ 2

THE cults and the philosophies we have just described were not the only elements in the religious life and thought of the Empire. Not even remotely. But they were among the dominant elements, and they could not but have influenced every educated citizen of the Empire. That excluded, of course, the humble Nazarenes in faroff Palestine. They were neither educated, nor citizens of the Empire. They were merely Palestinian Jews, poor artisans and peasants most of whom knew no tongue save the Aramaic dialect used in their homes and synagogues. And if in later years the Nazarene faith began to take on the color and shape of those heathen cults and strange philosophies, these Palestinian Nazarenes were not in the least responsible. It was one from outside the original brotherhood, a Jew from beyond the borders of Palestine, who was responsible. It was Saul of Tarsus who brought on that change.

Saul was both a Jew and a citizen of the Empire. He was born in Tarsus in Asia Minor, a city of some consequence as a trading center and a seat of learning; and while still a boy he seems to have distinguished himself as a student. A Pharisee, and the descendant of Pharisees, his chief training was in Rabbinic law; but he also knew Greek, and must have had rather more than a passing acquaintance with Greek and Alexandrian philosophy. Most important of all, he must very early [ p. 280 ] have learnt from slaves in the household, or from Gentile playmates, of the mystery cults which were prevalent in his native city, and of the savior-gods in whom the masses put their impassioned trust. . . . Despite these early heathen influences, however, Saul remained a Jew. When grown to young manhood he even went down from Tarsus to Jerusalem so that he might complete his religious studies under the great Rabbi Gamaliel there. (It seems not to have been uncommon for the sons of wealthy Jews living outside the homeland to come to Jerusalem to finish their education.) And there in Jerusalem Saul for the first time came in contact with the Nazarenes. . . . Now Saul was a person of very violent likes and dislikes, and when he heard what those Nazarenes were preaching, he was convulsed with anger. He is said to have been an epileptic, and certainly he was a man of strange temperament. Whatever he did, he did with an intensity and an extravagance that were distinctly abnormal. So that when he took his initial dislike to the Nazarenes, he could not merely shrug his shoulders in [ p. 281 ] disapproval and let them he. He had to persecute them. Nor was he content with persecuting them merely in Jerusalem. On hearing that their movement was growing virulently in Damascus, he actually dropped his studies and set out to run them down there as well.

But on the way to Damascus a queer thing happened to him. He was suddenly overcome by a seizure of some sort, and in a trance a vision came to him of the resurrected Jesus. A “light from heaven” shone round about him, and a voice cried out: “Saul, Saul, why dost thou persecute me?” And when, trembling and astonished, Saul came to himself, behold he was a changed man!

When he got to Damascus he arose in the synagogue, and instead of persecuting the Nazarenes, he began actually to praise them. He had become a complete convert to their cause, believing in the Messiahship of Jesus and in his resurrection with an unshakable conviction.

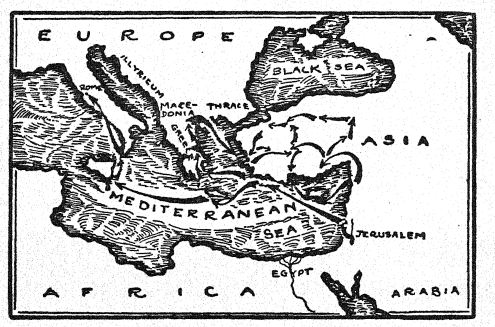

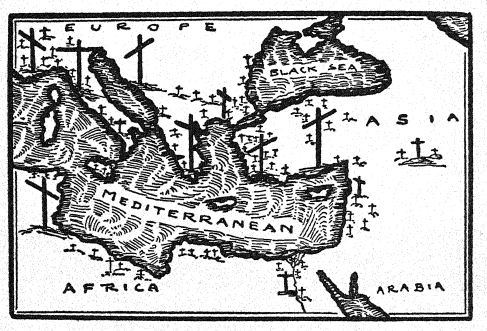

Saul had never seen Jesus in the flesh or come under the spell of his loving gospel. But that made no difference to him. Actually he was but little interested in the gospel of the man Jesus; he was interested only in the death and rebirth of the savior-god, Christ. Christos is the Greek word for “Anointed One,” and Saul, whose mother tongue was Greek, built his whole personal faith around that word. He became the great preacher of “Christ crucified,” journeying about all over the Empire, to Cilicia, Galatia, Macedonia, the islands of the Mediterranean, and even Rome, in a great passion to have the world share with him his belief. . .

[ p. 282 ]

¶ 3

AND thus at last Christianity as a world religion was really founded. Jesus had not founded what the world calls Christianity, for Jesus had lived and died a Jew within the fold of Judaism. Jesus had lived and labored merely to guide his fellow Jews to those elements in their own Jewish religion which might make their sorry lives glorious. He had tried but to lead them to salvation through distinctly Jewish channels, and he had on occasion even turned away heathens who had come to him for help. He was not the founder of Christianity, but its foundling. …

Nor had his immediate disciples created the new faith. They had remained conforming Jews, and the Messiah put forward by them had all along been the Jewish [ p. 283 ] Messiah. The Kingdom of Heaven they had dreamed of inheriting was a kingdom reserved primarily for Jews.

Nor was it Saul, the studious young Pharisee, who founded the new faith, but his other self, Paul, the citizen of Rome. (He changed his name sometime after the conversion.) There are two hostile selves, the Saul and the Paul, in almost every sensitive Jew who has ever lived in the Gentile world. The one tries to hold him fast within the small and limiting circle of his own people; the other tries to draw him out into the wide, free circle of the world. And because in this instance the man was of so intense a nature, the conflict was all the more marked. What-time the Saul in him was triumphant, this man was ready actually to murder every Jew in whom the Paul so much as lifted its head. And when the Paul in him got the upper hand, he was all for putting an end to the Sauls. He openly proclaimed that all the laws which kept Jew apart from Gentile were now no longer of any worth. With the coming of the Christ there had come a new dispensation, he believed. Circumcized and uncircumcized were now alike, and he that ate “defilement” was no less in the sight of Christ than he that scrupulously kept all the Mosaic laws. For the Christ was not the Messiah merely of the Jews; he was the Savior of all mankind. The shedding of his blood had washed away the sin of all men, and now one need but believe in him to be saved. No more than that was demanded: believe in Christ, and one was redeemed!

And it was due to this breaking down of the “Wall of Law” that the Nazarene faith, so long obscure and [ p. 284 ] unnoticed in tiny Judea, flooded out and inundated the world.

It is unfair to compare Paul to Jesus, for the two belonged spiritually and intellectually to entirely different orders of men. The one was a prophet and a dreamer of dreams; the other was an organizer and a builder of churches. In his own class Paul was one of the stupendously great men of the earth. If at moments he could be violent and ungracious, he was nevertheless a superb statesman. And he was possessed of an energy, a courage, and an indomitable will, the like of which have rarely been known in all the history of great men. Again and again he was scourged and imprisoned by the outraged elders of the synagogues in which he tried to preach. (Paul usually tried to obtain a hearing in the local synagogue whenever he arrived in a strange city.) Mobs were set on him; more than once he had to flee for his life. The orthodox Jews looked on him as an apostate, and some even of his own fellow Nazarenes fought to depose him from leadership. All the years of his ministry he was plagued by Jews who hated him, Nazarenes who distrusted him, and Gentiles who could hardly make out what he was talking about. And yet he persisted, never resting from his grueling labor of carrying his Christ to the Gentiles, incessantly running to and fro, incessantly preaching, writing, arguing, and comforting, until at last, a tired and broken man, he died a martyr’s death in the city of Rome. . . .

¶ 4

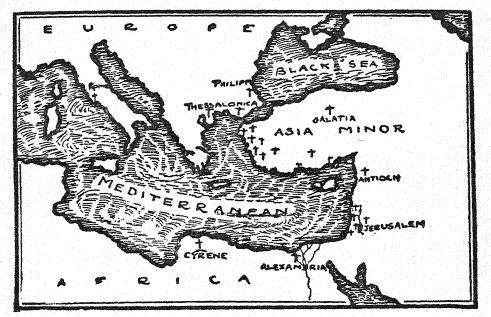

IT was in the year 67, according to tradition, that Paul was beheaded by the Romans. He had spent perhaps [ p. 285 ] thirty years in the labor of spreading the idea of Christ, and by the time of his death that idea had already struck root far and wide in the Empire. It had divorced itself from Judaism, taking over the Sunday of the Mithraists in place of the Jewish Sabbath, and substituting Mithraist ritual for Temple sacrifice. In most of the cities there were already thriving Christian brotherhoods, little secret societies much like those of the mysteries, but with greater proselyting passion. While the leaders were still for the most part converted Jews, the membership was largely of pagan origin. And as, with the passing of the years, the pagan element grew ever more preponderant, pagan ideas came more and more to dominate the religion. The life-story of Jesus was embellished with a whole new array of marvels and miracles, and the man himself was made over into a veritable mystery savior-god. His character and nature fell into the maw of an alien philosophy, and then came drooling out in sodden and swollen distortion. He became the Lamb whose blood washed away all sin. [1] He became the Son of God super naturally conceived by the Virgin Mary when the Holy Ghost of God the Father entered into her womb. He became the Logos and the Avatar and the Savior. And throughout the Empire little churches were to be found in which his pictures (extraordinarily [ p. 286 ] like those of Horus) were worshipped, and in which his “flesh and blood” (amazingly like the symbols used in the magical rites of Mithras) were taken in communion.

That is why this section is entitled “What Happened in Europe.” Although the religion of Jesus and of the first disciples was distinctly Oriental, although the whole Messiah idea was markedly a thing out of the East, the religion about a Savior Christ was largely European. And it was no less far a cry from the one to the other than was the distance from Nazareth to Rome. Indeed, one gravely doubts whether Jesus, the simple peasant teacher in hilly Galilee, would have known who in the world that Savior Christ was! . . .

But it was inevitable for that change to come about. Christianity in those years was gaining too many converts too rapidly. It would not have been so bad had they been converts from a world of ignorance — that is, converts who had naught to forget when they came over to the new faith. But they were converts instead from a world of what we would call stupidity. Their minds were crowded with fears and superstitions and magic rites and extravagant dogmas which they were supposed to forget when they became Christians — but they never succeeded in forgetting them . So it was inevitable, we repeat, that this new faith, oversuccessful as it was in hurriedly displacing the old, should in the end become very like unto the old.

But for all that growing likeness, a significant element of disparity always remained. There was a zeal, a missionary ardor, in the early church that was largely unknown in the older cults. There was a constant running [ p. 287 ] to and fro of prophets and deacons from one center to another, and a diligent spreading of tracts and epistles among all who could read. There were, for instance, the letters of Paul giving advice on matters of administration, and explaining matters of doctrine to various of the little churches he had founded. And later there were the Gospels. The Gospels, as we now have them, could not have been written by the disciples whose names they bear, for they are written in Greek, and the native language of most of those disciples was Aramaic. Nor do they seem to have been direct translations from Aramaic accounts. Scholars today are agreed that the earliest of them is the one entitled “The Gospel according to Mark,” and they date it about the year 65 — that is, thirty-five years after the crucifixion. The latest of the Gospels, that of John, with its unconscious [ p. 288 ] effort to make Jesus fit the Logos, could not have been written (according to many of the scholars) until well after the year 100. Such writings must have been circulated freely by the missionaries wherever they ventured, and it is evident that they were distinctly effective. No such testaments could be offered by the priests of Mithras, Cybele, or Attis, for their deities were after all mythical. Only the Christians had a real man to worship: a unique and divine man, it is true, but nevertheless a person who had known human woe and pain, who had suffered, and who had for at least three days been dead. That element of naturalism, of closeness to human reality, must have made Christianity a faith of extraordinary attractiveness.

And being so attractive, it vapidly began to eat into the ranks of the other mysteries. It won away their followers at such a rate that it began at last to present a distinct menace to the Roman governors. Spread everywhere, from the Thames to the Euphrates, its halfsecret brotherhoods formed what amounted to an empire within the Empire. Its initiates fanatically refused to conduct themselves like Roman gentlemen. They opposed the basic institutions of the Roman social system, and they hated the theater and the gladiatorial shows, the chief amusements of the time. Worse still, they refused absolutely to worship the Emperor as god, thus openly inviting the suspicion of disloyalty to Rome. So attempts at suppression were in the nature of things almost unavoidable.

At first the Christians were persecuted only to gratify the lusts of the Roman mob; but later more systematic efforts had to be made. After the year 303 the imperial [ p. 289 ] government realized that its very existence was in danger so long as Christianity was allowed to flourish, and it therefore made one supreme attempt utterly to annihilate the revolutionary cult. The churches were burnt down, all copies of the Gospels and Epistles were destroyed, and the Christians themselves were martyred by the score. The government seemed determined to stamp out Christianity, as modern governments seek to stamp out Communism or Pacifism or Anarchism. (Early Christianity, according to Prof. Gilbert Murray, might indeed have seemed to the Romans what “a blend of pacifist international socialist with some mystical Indian sect, drawing its supporters mainly from an oppressed and ill-liked foreign proletariat, such as the 'hunkey’ population of some big American towns, full of the noblest moral professions but at the same time aliens,” would seem to modern men of affairs.) There were tortures and executions beyond number, and the jails were filled with Christian devotees.

But nevertheless the movement grew. There was a wondrous comfort in that religion, a mighty zeal that made it possible for the martyrs to go to their death actually with a smile on their lips. It took vile slaves out of the slums where they rotted, and somehow breathed supernal heroism into them. It told them that sacrifice was at the very core of righteousness, that death for the truth could mean only life everlasting. Had not the Savior himself died for the truth? Of a surety, therefore, he would not desert those who died likewise. He would take up their tortured souls in his comforting arms, and heal them in Heaven where he reigned. Death could have no sting for them, nor the grave any victory [ p. 290 ] for the Crucified Christ would be with them and bring them through to blessedness eternal! . . .

So no matter how madly Rome hounded the Christians, Christianity could not be crushed.

¶ 5

AND then came Constantine and, in the year 313, an end to the persecutions. Constantine was born out inServia, and is reported to have been the illegitimate son of a Roman general and a village barmaid. He was inordinately ambitious, and by dint of much energy, intrigue, and not a little use of murder, he managed to raise himself actually to the imperial throne. But his position was challenged by a rival emperor, and in his dire need of help from any and every quarter, Constantine suddenly turned to the Christians. With characteristic [ p. 291 ] shrewdness he realized that those fanatical Christ- worshippers were a power to be reckoned with. Here they were, established everywhere, and possessed of an insuperable will-to-live. Constantine probably had no clear idea as to what it was they really believed. He may have thought them Mithraists who for some queer reason, best known to themselves, worshipped a cross. But he did know that they were becoming politically of superlative importance. So he began officially to favor them, showering their churches with wealth. He had the intelligence to see that they were the sole unifying force left in the disrupted empire. They formed one vast and powerful brotherhood that ramified everywhere. And Constantine, whose chief concern was the finding of some way of bolstering up the tottering empire, felt forced to resort to them for help.

And thus it came about that a fervent hope in the heart of an obscure little Levantine race, and a sweet doctrine of love and peace preached by a simple young Levantine peasant, became three hundred years later the official religion of the greatest empire the world had ever knownl …

¶ 6

BUT it was a costly triumph for Christianity, as every other such triumph has been in all history. What happened to Buddhism when it set out to conquer the Far East, now happened also to Christianity in the West. It became an official and successful institution — and so degenerated. A faith cannot be institutionalized, for it is a thing of the spirit Even dogmas or rites, which are things almost of the flesh, cannot be organized [ p. 292 ] beyond certain bounds. So that even after Christianity became primarily a thing of dogmas and rites, it nevertheless began to crack and crumble. All sorts of schisms occurred. In the process of organizing the idea of the Christ, a myriad differences arose. Paul had used his theological terms rather loosely, and had spoken of God, the Son of God, and the Spirit of God. Now, were these three the names of one Person or three? Was the Son of God actually God Himself, or merely similar to God? Was the Spirit of God a part of or separate from God? . . . Paul had spoken of a Divine Christ and a human Jesus. Well, then, were these two beings one, or really two? And if they were one, when had they coalesced? Had Jesus never been a human being, but the Christ from the very beginning of creation? Or had he become united with the Christ at the moment of his conception or birth? Or had the Christ descended upon him when at the age of thirty he was baptized by John? . . . Paul had spoken of Jesus as a Savior. He had said that God, the loving Father, had sacrificed His onlybegotten Son to redeem the world. But why should God have found it necessary to make any such sacrifice? To whom could He, the All-powerful, be beholden? For that matter, if He was indeed the God of forgiveness, why had He not forgiven without ever bringing the agony of the crucifixion to His beloved Son? Could it be that there were really two Gods: the unforgiving God of the Old Testament, and the forgiving God of the New? . . .

Scores of such questions arose to perplex and divide the organizers of the religion. Jesus had not been conscious of even the most ponderous of such questions. [ p. 293 ] That dear, fervent young preacher, who had lived and died in the sublimity of a simple faith, could never possibly have been conscious of them. Had he heard them posed, he would probably have shaken his head in mute bewilderment. … But in Europe three centuries later, such abstruse metaphysical enigmas were considered the very bone and sinew of the religion. The early church fathers disputed over them with a heat and rancor that sometimes did not stop even at murder. When one puts beside the Gospel accounts of the preachings of Jesus, the official records of the wranglings and bickerings of those church fathers, one feels that here is to be found the most tragic and sordid epic of frustration that the whole history of mankind can tell. …

¶ 7

BUT the rest of the chapters of that epic cannot be told here. In all fairness no more may be done here for Christianity than has been done for the other great religions of the world, and having told of the founding of the church, and of its original faith, room remains for no more than a broad hint as to its later development.

More than sixteen hundred years have passed since Christianity was made the state religion in the decadent Roman Empire. Throughout all those years it has been extending its borders, winning new converts in every pagan land on earth. It is estimated that at the present time about one-third of the entire population of the world is Christian — approximately five hundred and sixty-five million souls. There is hardly a region on earth where there is not a church bearing its name or, in default of that, some zealous missionary trying [ p. 294 ] his utmost to erect a church. And of course, it is to the spirit of Paul regnant in Christendom that one must credit that enormous expansion. It is because countless monks and healers and warriors and saints have felt Paul’s call to go out and win the heathen to Christ, that today more souls are turned to Christ than to any other deity on earth.

But as we have already pointed out, these wholesale increases in numbers were not made save at a high price. Grave compromises had to he made everywhere with the defeated cults. Just as Buddha had to he idolized before he could conquer the East, so Jesus had to be idolized to gain his victory over the West. His mother had to be idolized, too, for pagan Europe loved its goddesses too intensely to consent to forswear them entirely. Indeed, during the medieval centuries Mary seems to have been revered, in practice if not in dogma, even more than her son. Much of the old love for Isis, and especially for Cybele, the great Mother of the Gods, was taken over into the church and translated into the worship of Mary, the Mother of Christ. . . . Similarly the worship of the old local deities was made a part of Christianity. The pagan gods and goddesses were discreetly made over into Christian saints, as is instanced by the case of St. Bridget. Their “relics” were sold far and wide in Christendom as fetishes guaranteed to ward off evil; and their ancient festive days were made part of the Christian calendar. The Roman Parilia in April became the Festival of St. George, and the pagan midsummer orgy in June was converted into the Festival of St. John; the holy day of Diana in August became the Festival of the Assumption of The [ p. 295 ] Virgin; and the Celtic feast of the dead in November was changed into the Festival of All Souls. The twentyfifth of December — the winter solstice according to ancient reckoning — celebrated as the birthday of the sungod of Mithraism, was accepted as the birthday of Christ, and the spring rites in connection with the death and rebirth of the mystery gods were converted into the Easter rites of the Crucifixion and Resurrection. . . .

Yet despite all these compromises, the new religion remained always heavens above the old. By assimilating pagan rites and myths and even god-names, Christianity became at last almost completely pagan in semblance; but it never became quite pagan in character. The Old Testament puritanism which had so marked the life of Jesus was never routed. It remained like a [ p. 296 ] moral emetic in the faith, forcing it to throw up the lust and license in the pagan rites it assimilated. If the spirit of Paul insisted that Cybele be taken over as the Mother of Christ, the spirit of Jesus insisted that her wild Corybantes with their lustful rites, and her holy eunuchs with their revolting perversions, be left severely behind.’ If the spirit of Paul demanded that the wild Celtic goddess named Bridget be accepted into Christianity, the spirit of Jesus demanded that first she be made lily-white and a saint. For the spirit of Jesus was innately Jewish and puritanical. It set its face hard against sacred prostitution and against all those other loosenesses and obscenities which arose out of the pagan’s free attitude toward sex. It hated license and beast passion in any form, whether it showed itself in feast, tourney, or battle. Inexorably it insisted on moral decency and restraint.

For that reason Christianity never became quite pagan in spirit. It remained too profoundly concerned with ethics. The old mysteries had been largely devoid of any distinct ethical emphasis. Most of them had promised immortality to their initiates as a reward for the mere mechanical performance of certain prescribed rites. Few of them had pried into the private life of an initiate to discover whether he was good or bad in his daily conduct. Few of them had been in the least interested in daily conduct. Morality had become completely religionized with most of them. They had maintained that to be saved one need be merely ritually proper, not ethically clean.

That was just where Christianity differed most radically from even the highest of the old mystery cults. [ p. 297 ] The spirit of Jesus flickering in Christianity made it at least nominally a religion of ethics. For Jesus, one must remember, had not been in the least concerned with ritual. Like every other great Jewish prophet, he had preached only ethics. And despite all the compromises of the world-conquering Pauls, that ethical emphasis in the teaching of Jesus persisted as a mighty leaven in the church. It gave to the early Christians that gentle nobility which history tells us graced their lives, and that heroic stubbornness which certainly marked their faith. It took hold of wild berserker races and somehow frowned them to order. It took hold of a savage Europe and somehow subdued it, civilized it. Not altogether, of course. The history of Europe, with all its wars and recurrent brutalities, can hardly be called the history of a civilized continent. Even the church itself, with its foul record of crusades and inquisitions and pogroms, cannot be said to have ever been really civilized. But that admission does not at all discredit the potency of the spirit of Jesus. It merely reveals how tremendous were the odds against it, how brutal was the world it sought to make divine. True, there were indeed Dark Ages in Europe when the power of the Church was at its height. But who knows how far darker they might have been, and how much longer they might have endured, had the Church not existed? True, there were indeed religious wars early and late in Christendom, but who knows how much bitterer and more devastating they might have been had they been tribal or racial wars. For wars were inevitable. A world with too little food and too much spleen simply had to [ p. 298 ] fight. If religious differences had not been at hand, other excuses would have been found for warring. And because those other excuses would have been deeperrooted and more primitive, they would no doubt have brought on infinitely more dreadful desolations. Wars for Christ, after all, could never be fought with a bloodlust utterly free and untrammeled. Their virulence was always partially sapped by the innate irony of their pretensions. The insistent pacifism of him in whose name those wars were fought could not but have had some tempering influence. None can doubt that the adoration of a Prince of Peace, the worship of a Good Shepherd, even though drugged almost dead with ritual, must have had a profound effect on the people. None can doubt /that the veneration of a gentle, loving, helpless youth as die very incarnation of perfection must have been as ice to the hot blood of the race. . . .

One must remember that Christianity came into a | jjworld that was sinking — sinking momentarily into an abyss of savagery. And it was almost the only force that sought to stay that debacle. It alone sought to keep civilization going. It failed. It could not keep : from failing. But be it said to its glory that at least it tried. . . .

¶ 8

HOWEVER, the glory of trying to save the world from bestiality belongs primarily to but one element alone in Christianity: the original Nazarene element. And that element, one must remember, was never dominant in the faith save during those years before it was really Christian. Once Paul came on the scene, the light of [ p. 299 ] the religion of Jesus began to fade, and the glare of the religion about Christ blazed over all. Yet though the light from Galilee faded, though for a while it died down into no more than a mere lingering spark, it never was quite snuffed out. For long centuries it smouldered there, barely living, barely keeping aglow. The compromising, theologizing, church-organizing religion about Christ blazed away unchallenged. In the West it gave rise to the Holy Roman Empire, that pathetic travesty which was never holy or Roman or imperial. In the East it created a farrago of sects arising from fatuous differences as to the metaphysical nature of Christ. . . . And then slowly that forgotten spark began to brighten once more. A devastating incursion of Huns and Saracens blew the spark to a flame. As never before in full six hundred years, the Christians began to think again of their suffering Savior. And like a mad fire the hope spread over Europe that the year 1000 would see the return of the Redeemer.

The year 1000 passed and no Redeemer came — but Europe was a little redeemed nevertheless. Its spirit was sobered and its life deepened. The hunger for salvation became too strong and acute to be allayed with mere ritual any longer. Men turned from what the Church of Christ insisted on offering them, and instead began to grope after the gospel of Jesus for themselves. They took to reading the Scriptures in their original tongues, and reading them they began to see at last how far the Church had wandered from the pristine truth. They discovered at last how shamelessly the priests had substituted rite for right, how flagrantly they had ritualized all morality. Heretical sects arose everywhere, and the [ p. 300 ] clerical authorities took alarm. Despotically they issued proclamations prohibiting the laity from even glancing at the Bible, and the priesthood from interpreting it save in accordance with the tradition of the Church. Then they instituted the Inquisition to see that the prohibition was observed.

But the Bible wai read nevertheless. Inquisitions and crusades and massacres proved of no avail. The flame of heresy burned on, and not even a sea of blood was enough to quench it. In the fourteenth century, Wycliffe did godly mischief in England; in the fifteenth, John Huss carried on in Bohemia; in the sixteenth, Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin led the protestant revolt throughout northern Europe. And thenceforth the Catholic Church ceased to be catholic any more even in the West. Land after land went over to the heretics, and European Christianity was cleft in two.

But one must not imagine that Protestantism was ever purely Nazarene in spirit — any more than Catholicism was ever unrelievedly Pauline. (Bishop Laud in the seventeenth century was a Protestant, while St. Francis of Assisi in the thirteenth century was a Catholic. . . .) Protestantism includes every type of religious thought and organization from “high church” Anglicanism to high-principled Quakerism, from ecstatic Methodism to relentlessly intellectual Unitarianism. Only slowly, and with many pangs, is even Protestantism shaking off the religion about Christ. Only slowly, very slowly, is it beating its way back to the religion of Jesus. . . .

And with that word we must leave the tale of what happened in Europe. The story of Christianity is long [ p. 301 ] and bewildering, for it stretches through twenty centuries and is written in a hundred tongues. In part it is a story of almost incredible rapacity and bitterness, of incessant war and intrigue, and low, greedy selfseeking. But in far larger part it is a story of wondrous kindness and saving grace. Though the Church of Christ may stand guilty of untold and untellable evil, the religion of Jesus, which is the little light glimmering behind that ecclesiastical bushel, has accomplished good sufficient to outweigh that evil tenfold. For it has made life livable for countless millions of harried souls. It has taken rich and poor, learned and ignorant, white, red, yellow, and black — it has taken them all and tried to show them a way to salvation. To all in pain it has held out a balm; to all in distress it has offered peace. To every man without distinction it has said: Jesus died for you! To every human creature on earth it has said: You too can be saved! And therein lies Christianity’s highest virtue. It has helped make the weak strong and the dejected happy. It has stilled the fear that howls in man’s breast, and crushed the unrest that gnaws at his soul. In a word, it has worked — in a measure. . . .

¶ Notes

Those who remember the description of the pagan Tauroboleum given in the chapter on Rome will find this good Christian hymn profoundly suggestive:

“There is a fountain filled with blood

Drawn from Emmanuels veins;

And sinners plunged beneath that flood

Lose all their guilty stains.” ↩︎