[ p. 127 ]

THE WRITINGS OF KWANG-DZE.

INTRODUCTION.

BRIEF NOTICES OF THE DIFFERENT BOOKS.

¶ BOOK I. HSIÂO-YÂO YÛ.

The three characters which form the title of this Book have all of them the ideagram  , (Ko), which gives the idea, as the Shwo Wän explains it, of ‘now walking, now halting.’ We might render the title by ‘Sauntering or Rambling at Ease;’ but it is the untroubled enjoyment of the mind which the author has in view. And this enjoyment is secured by the Tâo, though that character does not once occur in the Book. Kwang-Sze illustrates his thesis first by the cases of creatures, the largest and the smallest, showing that however different they may be in size, they should not pass judgment on one another, but may equally find their happiness in the Tâo. From this he advances to men, and from the cases of Yung-dze and Lieh-dze proceeds to that of one who finds his enjoyment in himself, independent of every other being or instrumentality; and we have the three important definitions of the accomplished Tâoist, as ‘the Perfect Man,’ ‘the Spirit-like Man,’ and ‘the Sagely Man.’ Those definitions are then illustrated;—the third in Yâo and Hsü Yû, and the second in the conversation between Kien Wû and Lien Shû. The description given in this conversation of the spirit-like man is very startling, and contains statements that are true only of Him who is a ‘Spirit,’ ‘the Blessed and only Potentate,’ ‘Who covereth Himself with light as with a garment, Who stretcheth out the heavens as a curtain, [ p. 128 ] Who layeth the beams of His chambers in the waters, Who maketh the clouds His chariot, Who walketh on the wings of the wind,’ ‘Who rideth on a cherub,’ ‘Who inhabiteth eternity.’ The most imaginative and metaphorical expressions in the Tâo Teh King about the power of the possessor of the Tâo are tame, compared with the language of our author. I call attention to it here, as he often uses the same extravagant style. There follows an illustration of ‘the Perfect Man,’ which is comparatively feeble, and part of it, so far as I can see, inappropriate, though Lin Hsî-kung says that all other interpretations of the sentences are ridiculous.

, (Ko), which gives the idea, as the Shwo Wän explains it, of ‘now walking, now halting.’ We might render the title by ‘Sauntering or Rambling at Ease;’ but it is the untroubled enjoyment of the mind which the author has in view. And this enjoyment is secured by the Tâo, though that character does not once occur in the Book. Kwang-Sze illustrates his thesis first by the cases of creatures, the largest and the smallest, showing that however different they may be in size, they should not pass judgment on one another, but may equally find their happiness in the Tâo. From this he advances to men, and from the cases of Yung-dze and Lieh-dze proceeds to that of one who finds his enjoyment in himself, independent of every other being or instrumentality; and we have the three important definitions of the accomplished Tâoist, as ‘the Perfect Man,’ ‘the Spirit-like Man,’ and ‘the Sagely Man.’ Those definitions are then illustrated;—the third in Yâo and Hsü Yû, and the second in the conversation between Kien Wû and Lien Shû. The description given in this conversation of the spirit-like man is very startling, and contains statements that are true only of Him who is a ‘Spirit,’ ‘the Blessed and only Potentate,’ ‘Who covereth Himself with light as with a garment, Who stretcheth out the heavens as a curtain, [ p. 128 ] Who layeth the beams of His chambers in the waters, Who maketh the clouds His chariot, Who walketh on the wings of the wind,’ ‘Who rideth on a cherub,’ ‘Who inhabiteth eternity.’ The most imaginative and metaphorical expressions in the Tâo Teh King about the power of the possessor of the Tâo are tame, compared with the language of our author. I call attention to it here, as he often uses the same extravagant style. There follows an illustration of ‘the Perfect Man,’ which is comparatively feeble, and part of it, so far as I can see, inappropriate, though Lin Hsî-kung says that all other interpretations of the sentences are ridiculous.

In the seventh and last paragraph we have two illustrations that nothing is really useless, if only used Tâoistically; ‘to the same effect,’ says Ziâo Hung, ‘as Confucius in the Analects, XVII, ii.’ They hang loosely, however, from what precedes.

An old view of the Book was that Kwang-dze intended himself by the great phäng, ‘which,’ says Lû Shû-kih, ‘is wide of the mark.’

¶ BOOK II. KHÎ WÛ LUN.

Mr. Balfour has translated this title by ‘Essay on the Uniformity of All Things;’ and, the subject of the Book being thus misconceived, his translation of it could not fail to be very incorrect. The Chinese critics, I may say without exception, construe the title as I have done. The second and third characters, Wû Lun, are taken together, and mean ‘Discussions about Things,’ equivalent to our ‘Controversies.’ They are under the government of the first character Khî, used as a verb, with the signification of ‘Harmonising,’ or ‘Adjusting.’ Let me illustrate this by condensing a passage from the ‘Supplementary Commentary of a Mr. Kang, a sub-secretary of the Imperial Chancery,’ of the Ming dynasty (  ). He says, ‘What Kwang-dze calls “Discussions about Things” has reference to the various branches of the numerous schools, each of which has its own views, conflicting with [ p. 129 ] the views of the others.’ He goes on to show that if they would only adopt the method pointed out by Kwang-dze, 'their controversies would be adjusted (

). He says, ‘What Kwang-dze calls “Discussions about Things” has reference to the various branches of the numerous schools, each of which has its own views, conflicting with [ p. 129 ] the views of the others.’ He goes on to show that if they would only adopt the method pointed out by Kwang-dze, 'their controversies would be adjusted (  ) using the first Khî in the passive voice.

) using the first Khî in the passive voice.

This then was the theme of our author in this Book. It must be left for the reader to discover from the translation how he pursues it. I pointed out a peculiarity in the former Book, that though the idea of the Tâo underlies it all, the term itself is never allowed to appear. Not only does the same idea underlie this Book, but the name is frequently employed. The Tâo is the panacea for the evils of controversy, the solvent through the use of which the different views of men may be made to disappear.

That the Tâo is not a Personal name in the conception of Kwang-dze is seen in several passages. We have not to go beyond the phenomena of nature to discover the reason of their being what they are; nor have we to go beyond the bigoted egoism and vaingloriousness of controversialists to find the explanation of their discussions, various as these are, and confounding like the sounds of the wind among the trees of a forest. To man, neither in nature nor in the sphere of knowledge, is there any other ‘Heaven’ but what belongs to his own mind. That is his only ‘True Ruler.’ If there be any other, we do not see His form, nor any traces of His acting. Things come about in their proper course. We cannot advance any proof of Creation. Whether we assume that there was something ‘in the beginning’ or nothing, we are equally landed in contradiction and absurdity. Let us stop at the limit of what we know, and not try to advance a step beyond it.

Towards the end of the Book our author’s agnosticism seems to reach its farthest point. All human experience is spoken of as a dream or as ‘illusion.’ He who calls another a dreamer does not know that he is not dreaming himself. One and another commentator discover in such utterances something very like the Buddhist doctrine that all life is but so much illusion (  ). This notion has its consummation in the story with which the Book concludes. [ p. 130 ] Kwang-dze had dreamt that he was a butterfly. When he awoke, and was himself again, he did not know whether he, Kwang Kâu, had been dreaming that he was a butterfly, or was now a butterfly dreaming that it was Kwang Kâu. And yet he adds that there must be a difference between Kâu and a butterfly, but he does not say what that difference is. But had he ever dreamt that he was a butterfly, so as to lose the consciousness of his personal identity as Kwang Kâu? I do not think so. One may, perhaps, lose that consciousness in the state of insanity; but the language of Young is not sufficiently guarded when he writes of

). This notion has its consummation in the story with which the Book concludes. [ p. 130 ] Kwang-dze had dreamt that he was a butterfly. When he awoke, and was himself again, he did not know whether he, Kwang Kâu, had been dreaming that he was a butterfly, or was now a butterfly dreaming that it was Kwang Kâu. And yet he adds that there must be a difference between Kâu and a butterfly, but he does not say what that difference is. But had he ever dreamt that he was a butterfly, so as to lose the consciousness of his personal identity as Kwang Kâu? I do not think so. One may, perhaps, lose that consciousness in the state of insanity; but the language of Young is not sufficiently guarded when he writes of

‘Dreams, where thought, in fancy’s maze, runs mad.’

When dreaming, our thoughts are not conditioned by the categories of time and space; but the conviction of our identity is never lost.

¶ BOOK III. YANG SHANG KÛ.

‘The Lord of Life’ is the Tâo. It is to this that we are indebted for the origin of life and for the preservation of it. Though not a Personal Being, it is here spoken of as if it were,—‘the Lord of Life;’ just as in the preceding Book it is made to appear as ‘a True Governor,’ and ‘a True Ruler.’ But how can we nourish the Tâo? The reply is, By avoiding all striving to do so; by a passionless, unstraining performance of what we have to do in our position in life; simply allowing the Tâo to guide and nourish us, without doing anything to please ourselves or to counteract the tendency of our being to decay and death.

Par. 1 exhibits the injury arising from not thus nourishing the life, and sets forth the rule we are to pursue.

Par. 2 illustrates the observance of the rule by the perfect skill with which the cook of the ruler Wän-hui of Wei cut up the oxen for his employer without trouble to himself, or injury to his knife.

[ p. 131 ]

Par. 3 illustrates the result of a neglect of one of the cautions in par. 1 to a certain master of the Left, who had brought on himself dismemberment in the loss of one of his feet.

Par. 4 shows how even Lâo-dze had failed in nourishing ‘the Lord of Life’ by neglecting the other caution, and allowing in his good-doing an admixture of human feeling, which produced in his disciples a regard for him that was inconsistent with the nature of the Tâo, and made them wail for him excessively on his death. This is the most remarkable portion of the Book, and it is followed by a sentence which implies that the existence of man’s spirit continues after death has taken place. His body is intended by the ‘faggots’ that are consumed by the fire. That fire represents the spirit which may be transferred elsewhere.

Some commentators dwell on the analogy between this and the Buddhistic transrotation of births; which latter teaching, however, they do not seem to understand. Others say that ‘the nourishment of the Lord of Life’ is simply acting as Yü did when he conveyed away the flooded waters ‘by doing that which gave him no trouble;’—see Mencius, IV, ii, 26.

In Kwang-dze there are various other stories of the same character as that about king Wän-hui’s cook,—e. g. XIX, 3 and XXII, 9. They are instances of the dexterity acquired by habit, and should hardly be pressed into the service of the doctrine of the Tâo.

¶ BOOK IV. ZÄN KIEN SHIH.

A man has his place among other men in the world; he is a member, while he lives, of the body of humanity. And as he has his place in society, so also he has his special duties to discharge, according to his position, and his relation to others. Tâoist writers refer to this Book as a proof of the practical character of the writings of Kwang-dze.

[ p. 132 ]

They are right to a certain extent in doing so; but the cases of relationship which are exhibited and prescribed for are of so peculiar a character, that the Book is of little value as a directory of human conduct and duty. In the first two paragraphs we have the case of Yen Hui, who wishes to go to Wei, and try to reform the character and government of its oppressive ruler; in the third and fourth, that of the duke of Sheh, who has been entrusted by the king of Khû with a difficult mission to the court of Khî, which is occasioning him much anxiety and apprehension; and in the fifth, that of a Yen Ho, who is about to undertake the office of teacher to the son of duke Ling of Wei, a young man with a very bad natural disposition. The other four paragraphs do not seem to come in naturally after these three cases, being occupied with two immense and wonderful trees, the case of a poor deformed cripple, and the lecture for the benefit of Confucius by ‘the madman of Khû.’ In all these last paragraphs, the theme is the usefulness, to the party himself at least, of being of no use.

Confucius is the principal speaker in the first four paragraphs. In what he says to Yen Hui and the duke of Sheh there is much that is shrewd and good; but we prefer the practical style of his teachings, as related by his own disciples in the Confucian Analects. Possibly, it was the object of Kwang-dze to exhibit his teaching, as containing, without his being aware of it, much of the mystical character of the Tâoistic system. His conversation with the duke of Sheh, however, is less obnoxious to this charge than what he is made to say to Yen Hui. The adviser of Yen Ho is a Kü Po-yü, a disciple of Confucius, who still has a place in the sage’s temples.

In the conclusion, the Tâoism of our author comes out in contrast with the methods of Confucius. His object in the whole treatise, perhaps, was to show how ‘the doing nothing, and yet thereby doing everything,’ was the method to be pursued in all the intercourses of society.

[ p. 133 ]

¶ BOOK V. TEH KHUNG FÛ.

The fû (  ) consisted in the earliest times of two slips of bamboo made with certain marks, so as to fit to each other exactly, and held by the two parties to any agreement or covenant. By the production and comparison of the slips, the parties verified their mutual relation; and the claim of the one and the obligation of the other were sufficiently established. ‘Seal’ seems the best translation of the character in this title.

) consisted in the earliest times of two slips of bamboo made with certain marks, so as to fit to each other exactly, and held by the two parties to any agreement or covenant. By the production and comparison of the slips, the parties verified their mutual relation; and the claim of the one and the obligation of the other were sufficiently established. ‘Seal’ seems the best translation of the character in this title.

By ‘virtue’ (  ) we must understand the characteristics of the Tâo. Where those existed in their full proportions in any individual, there was sure to be the evidence or proof of them in the influence which he exerted in all his intercourse with other men; and the illustration of this is the subject of this Book, in all its five paragraphs. That influence is the ‘Seal’ set on him, proving him to be a true child of the Tâo.

) we must understand the characteristics of the Tâo. Where those existed in their full proportions in any individual, there was sure to be the evidence or proof of them in the influence which he exerted in all his intercourse with other men; and the illustration of this is the subject of this Book, in all its five paragraphs. That influence is the ‘Seal’ set on him, proving him to be a true child of the Tâo.

The heroes, as I may call them, of the first three paragraphs are all men who had lost their feet, having been reduced to that condition as a punishment, just or unjust, of certain offences; and those of the last two are distinguished by their extraordinary ugliness or disgusting deformity. But neither the loss of their feet nor their deformities trouble the serenity of their own minds, or interfere with the effects of their teaching and character upon others; so superior is their virtue to the deficiencies in their outward appearance.

Various brief descriptions of the Tâo are interspersed in the Book. The most remarkable of them are those in par. 1, where it appears as ‘that in which there is no element of falsehood,’ and as ‘the author of all the Changes or Transformations’ in the world. The sentences where these occur are thus translated by Mr. Balfour:—‘He seeks to know Him in whom is nothing false. He would not be affected by the instability of creation; even if his life were involved in the general destruction, he would yet hold firmly to his faith (in God).’ And he observes in a [ p. 134 ] note, that the first short sentence ‘is explained by the commentators as referring to Kän Zâi (  ), the term used by the Tâoist school for God.’ But we met with that name and synonyms of it in Book II, par. 2, as appellations of the Tâo, coupled with the denial of its personality. Kän Zâi, ‘the True Governor or Lord,’ may be used as a designation for god or God, but the Tâoist school denies the existence of a Personal Being, to whom we are accustomed to apply that name.

), the term used by the Tâoist school for God.’ But we met with that name and synonyms of it in Book II, par. 2, as appellations of the Tâo, coupled with the denial of its personality. Kän Zâi, ‘the True Governor or Lord,’ may be used as a designation for god or God, but the Tâoist school denies the existence of a Personal Being, to whom we are accustomed to apply that name.

Hui-dze, the sophist and friend of Kwang-dze, is introduced in the conclusion as disputing with him the propriety of his representing the Master of the Tâo as being still ‘a man;’ and is beaten down by him with a repetition of his assertions, and a reference to some of Hui-dze’s well-known peculiarities. What would Kwang-dze have said, if his opponent had affirmed that his instances were all imaginary, and that no man had ever appeared who could appeal to his possession of such a ‘seal’ to his virtues and influence as he described?

Lû Fang-wäng compares with the tenor of this Book what we find in Mencius, VII, i, 21, about the nature of the superior man. The analogy between them, however, is very faint and incomplete.

¶ BOOK VI. TÂ ZUNG SHIH.

So I translate the title of this Book, taking Zung as a verb, and Zung Shih as = ‘The Master who is Honoured.’ Some critics take Zung in the sense of ‘Originator,’ in which it is employed in the Tâo Teh King, lxx, 2. Whichever rendering be adopted, there is no doubt that the title is intended to be a designation of the Tâo; and no one of our author’s Books is more important for the understanding of his system of thought.

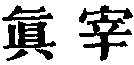

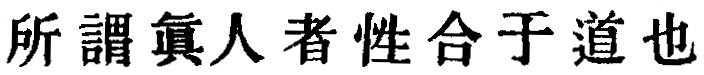

The key to it is found in the first of its fifteen paragraphs. There are in man two elements;-the Heavenly or Tâoistic, and the human. The disciple of the Tâo, recognising them both, cultivates what he knows as a man [ p. 135 ] so as to become entirely conformed to the action of the Tâo, and submissive in all the most painful experiences in his lot, which is entirely ordered by it. A seal will be set on the wisdom of this course hereafter, when he has completed the period of his existence on earth, and returns to the state of non-existence, from which the Tâo called him to be born as a man. In the meantime he may attain to be the True man possessing the True knowledge.

Our author then proceeds to give his readers in five paragraphs his idea of the True Man. Mr. Balfour says that this name is to be understood ‘in the esoteric sense, the partaking of the essence of divinity,’ and he translates it by ‘the Divine Man.’ But we have no right to introduce here the terms ‘divine’ and ‘divinity.’ Nan-hwâi (VII, 5b) gives a short definition of the name which is more to the point:—'What we call “the True Man” is one whose nature is in agreement with the Tâo (  ) and the commentator adds in a note, ‘Such men as Fû-hsî, Hwang-Tî, and Lâo Tan.’ The Khang-hsî dictionary commences its account of the character

) and the commentator adds in a note, ‘Such men as Fû-hsî, Hwang-Tî, and Lâo Tan.’ The Khang-hsî dictionary commences its account of the character  or ‘True’ by a definition of the True Man taken from the Shwo Wän as a

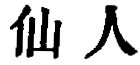

or ‘True’ by a definition of the True Man taken from the Shwo Wän as a  , ‘a recluse of the mountain, whose bodily form has been changed, and who ascends to heaven;’ but when that earliest dictionary was made, Tâoism had entered into a new phase, different from what it had in the time of our author. The most prominent characteristic of the True Man is that he is free from all exercise of thought and purpose, a being entirely passive in the hands of the Tâo. In par. 3 seven men are mentioned, good and worthy men, but inferior to the True.

, ‘a recluse of the mountain, whose bodily form has been changed, and who ascends to heaven;’ but when that earliest dictionary was made, Tâoism had entered into a new phase, different from what it had in the time of our author. The most prominent characteristic of the True Man is that he is free from all exercise of thought and purpose, a being entirely passive in the hands of the Tâo. In par. 3 seven men are mentioned, good and worthy men, but inferior to the True.

Having said what he had to say of the True Man, Kwang-dze comes in the seventh paragraph to speak directly of the Tâo itself, and describes it with many wonderful predicates which exalt it above our idea of God;—a concept and not a personality. He concludes by mentioning a number of ancient personages who had got the Tâo, and by it wrought wonders, beginning with a Shih-wei, who preceded Fû-hsî, and ending with Fû Yüeh, the minister of [ p. 136 ] Wû-ting, in the fourteenth century B. C., and who finally became a star in the eastern portion of the zodiac. Phäng Zû is also mentioned as living, through his possession of the Tâo, from the twenty-third century 13. C. to the seventh or later. The sun and moon and the constellation of the Great Bear are also mentioned as its possessors, and the fabulous Being called the Mother of the Western King. The whole passage is perplexing to the reader to the last degree.

The remaining paragraphs are mostly occupied with instances of learning the Tâo, and of its effects in making men superior to the infirmities of age and the most terrible deformities of person and calamities of penury; as ‘Tranquillity’ under all that might seem most calculated to disturb it. Very strange is the attempt at the conclusion of par. 8 apparently to trace the genesis of the knowledge of the Tâo. Confucius is introduced repeatedly as the expounder of Tâoism, and made to praise it as the ne plus ultra of human attainment.

¶ BOOK VII. YING TÎ WANG.

The first of the three characters in this title renders the translation of it somewhat perplexing. Ying has different meanings according as it is read in the first tone or in the third. In the first tone it is the symbol of what is right, or should be; in the third tone of answering or responding to. 1 prefer to take it here in the first tone. As Kwo, Hsiang says, ‘One who is free from mind or purpose of his own, and loves men to become transformed of themselves, is fit to be a Ruler or a King,’ and as Zhui Kwan, another early commentator, says, ‘He whose teaching is that which is without words, and makes men in the world act as if they were oxen or horses, is fit to be a Ruler or a King.’ This then is the object of the Book—to describe that government which exhibits the Tâo equally in the rulers and the ruled, the world of men all happy and good without purpose or effort.

It consists of seven paragraphs. The first shows us the model ruler in him of the line of Thâi, whom I have not [ p. 137 ] succeeded in identifying. The second shows us men under such a rule, uncontrolled and safe like the bird that flies high beyond the reach of the archer, and the mouse secure in its deep hole from its pursuers. The teacher in this portion is Khieh-yü, known in the Confucian school as ‘the madman of Khû,’ and he delivers his lesson in opposition to the heresy of a Zäh-kung Shih, or ‘Noon Beginning.’ In the third paragraph the speakers are ‘a nameless man,’ and a Thien Kän, or ‘Heaven Root.’ In the fourth paragraph Lâo-dze himself appears upon the stage, and lectures a Yang Dze-kü, the Yang Kû of Mencius. He concludes by saying that ‘where the intelligent kings took their stand could not be fathomed, and they found their enjoyment in (the realm of) nonentity.’

The fifth paragraph is longer, and tells us of the defeat of a wizard, a physiognomist in Käng, by Hû-dze, the master of the philosopher Lieh-dze, who is thereby delivered from the glamour which the cheat was throwing round him. I confess to not being able to understand the various processes by which Hû-dze foils the wizard and makes him run away. The whole story is told, and at greater length, in the second book of the collection ascribed to Lieh-dze, and the curious student may like to look at the translation of that work by Mr. Ernst Faber (Der Naturalismus bei den alten Chinesen sowohl nach der Seite des Pantheismus als des Sensualismus, oder die Sämmtlichen Werke des Philosophen Licius, 1877). The effect of the wizard’s defeat on Lieh-dze was great. He returned in great humility to his house, and did not go out of it for three years. He did the cooking for his wife, and fed the pigs as if he were feeding men. He returned to pure simplicity, and therein continued to the end of his life. But I do not see the connexion between this narrative and the government of the Rulers and Kings.

The sixth paragraph is a homily by our author himself on ‘non-action.’ It contains a good simile, comparing the mind of the perfect man to a mirror, which reflects faithfully what comes before it, but does not retain any image of it, when the mind is gone.

[ p. 138 ]

The last paragraph is an ingenious and interesting allegory relating how the gods of the southern and northern seas brought Chaos to an end by boring holes in him. Thereby they destroyed the primal simplicity, and according to Tâoism did Chaos an injury! On the whole I do not think that this Book, with which the more finished essays of Kwang-dze come to an end, is so successful as those that precede it.

¶ BOOK VIII. PHIEN MÂU.

This Book brings us to the Second Part of the writings of our author, embracing in all fifteen Books. Of the most important difference between the Books of the First and the other Parts some account has been given in the Introductory Chapter. We have here to do only with the different character of their titles, Those of the seven preceding Books are so many theses, and are believed to have been prefixed to them by Kwang-dze himself; those of this Book and the others that follow are believed to have been prefixed by Kwo Hsiang, and consist of two or three characters taken from the beginning, or near the beginning of the several Books, after the fashion of the names of the Books in the Confucian Analects, in the works of Mencius, and in our Hebrew Scriptures. Books VIII to XIII are considered to be supplementary to VII by Aû-yang Hsiû.

The title of this eighth Book, Phien Mâu, has been rendered by Mr. Balfour, after Dr. Williams, ‘Double Thumbs.’ But the Mâu, which may mean either the Thumb or the Great Toe, must be taken in the latter sense, being distinguished in this paragraph and elsewhere from Kih, ‘a finger,’ and expressly specified also as belonging to the foot. The character phien, as used here, is defined in the Khang-hsî dictionary as ‘anything additional growing out as an appendage or excrescence, a growing out at the side.’ This would seem to justify the translation of it by ‘double.’ But in paragraph 3, while the extra finger increases the number of the fingers, this growth on the foot is represented as diminishing the number of the toes. I must consider [ p. 139 ] the phien therefore as descriptive of an appendage by which the great toe was united to one or all of the other toes, and can think of no better rendering of the title than what I have given. It is told in the Zo Kwan (twenty-third year of duke Hsî) that the famous duke Wän of Zin had phien hsieh, that is, that his ribs presented the appearance of forming one bone. So much for the title.

The subject-matter of the Book seems strange to us; that, according to the Tâo, benevolence and righteousness are not natural growths of humanity, but excrescences on it, like the extra finger on the hand, and the membranous web of the toes. The weakness of the Tâoistic system begins to appear. Kwang-dze’s arguments in support of his position must be pronounced very feeble. The ancient Shun is introduced as the first who called in the two great virtues to distort and vex the world, keeping society for more than a thousand years in a state of uneasy excitement. Of course he assumes that prior to Shun, he does not say for how long a time (and in other places he makes decay to have begun earlier), the world had been in a state of paradisiacal innocence and simplicity, under the guidance of the Tâo, untroubled by any consideration of what was right and what was wrong, men passively allowing their nature to have its quiet development, and happy in that condition. All culture of art or music is wrong, and so it is wrong and injurious to be striving to manifest benevolence and to maintain righteousness.

He especially singles out two men, one of the twelfth century B. C., the famous Po-î, who died of hunger rather than acknowledge the dynasty of Kâu; and one of a more recent age, the robber Shih, a great leader of brigands, who brought himself by his deeds to an untimely end; and he sees nothing to choose between them. We must give our judgment for the teaching of Confucianism in preference to that of Tâoism, if our author can be regarded as a fair expositor of the latter. He is ingenious in his statements and illustrations, but he was, like his master Lâo-dze, only a dreamer.

[ p. 140 ]

¶ BOOK IX. MÂ THÎ.

‘Horses’ and ‘Hoofs’ are the first two characters of the Text, standing there in the relation of regent and regimen. The account of the teaching of the Book given by Lin Hsî-kung is so concise that I will avail myself of it. He says:—

‘Governing men is like governing horses. They may be governed in such a way as shall be injurious to them, just as Po-lâo governed the horse;—contrary to its true nature. His method was not different from that of the (first) potter and carpenter in dealing with clay and wood;—contrary to the nature of those substances. Notwithstanding this, one age after another has celebrated the skill of those parties;—not knowing what it is that constitutes the good and skilful government of men. Such government simply requires that men be made to fulfil their regular constant nature,—the qualities which they all possess in common, with which they are constituted by Heaven, and then be left to themselves. It was this which constituted the age of perfect virtue; but when the sages insisted on the practice of benevolence, righteousness, ceremonies, and music, then the people began to be without that perfect virtue. Not that they were in themselves different from what they had been, but those practices do not really belong to their regular nature; they arose from their neglecting the characteristics of the Tâo, and abandoning their natural constitution; it was the case of the skilful artisan cutting and hacking his raw materials in order to form vessels from them. There is no ground for doubting that Po-lâo’s management of horses gave them that knowledge with which they went on to play the part of thieves, or that it was the sages’ government of the people which made them devote themselves to the pursuit of gain;—it is impossible to deny the error of those sages.

‘There is but one idea in the Book from the beginning to the end;—it is an amplification of the expression in the preceding Book that “all men have their regular and constant [ p. 141 ] constitution,” and is the most easily construed of all Kwang-dze’s compositions. In consequence, however, of the wonderful touches of his pencil in describing the sympathy between men and other creatures in their primal state, some have imagined that there is a waste and embellishment of language, and doubted whether the Book is really his own, but thought it was written by some one in imitation of his style. I apprehend that no other hand would easily have attained to such a mastery of that style.’

There is no possibility of adjudicating definitely on the suspicion of the genuineness of the Book thus expressed in Hsî-kung’s concluding remarks. The same suspicion arose in my own mind in the process of translation. My surprise continues that our author did not perceive the absurdity of his notions of the primal state of men, and of his condemnation of the sages.

¶ BOOK X. KHÜ KHIEH.

It is observed by the commentator Kwei Kän-khüan that one idea runs through this Book:—that the most sage and wise men have ministered to theft and robbery, and that, if there were an end of sageness and wisdom, the world would be at rest. Between it and the previous Book there is a general agreement in argument and object, but in this the author expresses himself with greater vehemence, and almost goes to excess in his denunciation of the institutions of the sages.

The reader will agree with these accounts of the Book. Kwang-dze at times becomes weak in his attempts to establish his points. To my mind the most interesting portions of this Book and the last one are the full statements which we have in them of the happy state of men when the Tâo maintained its undisputed sway in the world, and the names of many of the early Tâoistic sovereigns. How can we suppose that anything would be gained by a return to the condition of primitive innocence and simplicity? The antagonism between Tâoism and Confucianism comes out in this Book very decidedly.

[ p. 142 ]

The title of the Book is taken from two characters in the first clause of the first paragraph.

¶ BOOK XI. ZÂI YÛ.

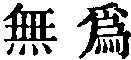

The two characters of the title are taken from the first sentence of the Text, but they express the subject of the Book more fully than the other titles in this Part do, and almost entitle it to a place in Part I. It is not easy to translate them, and Mr. Balfour renders them by ‘Leniency towards Faults,’ probably construing Zâi as equivalent to our preposition ‘in,’ which it often is. But Kwang-dze uses both Zâi and Yû as verbs, or blends them together, the chief force of the binomial compound being derived from the significance of the Zâi. Zâi is defined by Zhun (  ) which gives the idea of ‘preserving’ or ‘keeping intact,’ and Yû by Khwan (

) which gives the idea of ‘preserving’ or ‘keeping intact,’ and Yû by Khwan (  ),‘being indulgent’ or ‘forbearing.’ The two characters are afterwards exchanged for other two, wû wei (

),‘being indulgent’ or ‘forbearing.’ The two characters are afterwards exchanged for other two, wû wei (  ) ‘doing nothing,’ ‘inaction,’ a grand characteristic of the Tâo.

) ‘doing nothing,’ ‘inaction,’ a grand characteristic of the Tâo.

The following summary of the Book is taken from Hsüan Ying’s explanations of our author:—'The two characters Zâi Yû express the subject-matter of the Book, and “governing” points out the opposite error as the disease into which men are prone to fall. Let men be, and the tendencies of their nature will be at rest, and there will be no necessity for governing the world. Try to govern it, and the world will be full of trouble; and men will not be able to rest in the tendencies of their nature. These are the subjects of the first two paragraphs.

‘In the third paragraph we have the erroneous view of Zhui Khü that by government it was possible to make men’s minds good. He did not know that governing was a disturbing meddling with the minds of men; and how Lâo-dze set forth the evil of such government, going on till it be irretrievable. This long paragraph vigorously attacks the injury done by governing.

‘In the fourth paragraph, when Hwang-Tî questions [ p. 143 ] Kwang Khäng-dze, the latter sets aside his inquiry about the government of the world, and tells him about the government of himself; and in the fifth, when Yün Kiang asks Hung Mung about governing men, the latter tells him about the nourishing of the heart. These two great paragraphs set forth clearly the subtlest points in the policy of Let-a-be. Truly it is not an empty name.

‘In the two last paragraphs, Kwang in his own words and way sets forth, now by affirmation, and now by negation, the meaning of all that precedes.’

This summary of the Book will assist the reader in understanding it. For other remarks that will be helpful, I must refer him to the notes appended to the Text. The Book is not easy to understand or to translate; and a remark found in the Kiâ-khing edition of ‘the Ten Philosophers,’ by Lû Hsiû-fû, who died in 1279, was welcome to me, ‘If you cannot understand one or two sentences of Kwang-dze, it does not matter.’

¶ BOOK XII. THIEN TÎ.

The first two characters of the Book are adopted as its name;—Thien Tî, ‘Heaven and Earth.’ These are employed, not so much as the two greatest material forms in the universe, but as the Great Powers whose influences extend to all below and upon them. Silently and effectively, with entire spontaneity, their influence goes forth, and a rule and pattern is thus given to those on whom the business of the government of the world devolves. The one character ‘Heaven’ is employed throughout the Book as the denomination of this purposeless spontaneity which yet is so powerful.

Lû Shû-kih says:—‘This Book also sets forth clearly how the rulers of the world ought simply to act in accordance with the spontaneity of the virtue of Heaven; abjuring sageness and putting away knowledge; and doing nothing:—in this way the Tâo or proper Method of Government will be attained to. As to the coercive methods of Mo Tî [ p. 144 ] and Hui-dze, they only serve to distress those who follow them.’

This object of the Book appears, more or less distinctly, in most of the illustrative paragraphs; though, as has been pointed out in the notes upon it, several of them must be considered to be spurious. Paragraphs 6, 7, and 11 are thus called in question, and, as most readers will feel, with reason. From 13 to the end, the paragraphs are held to be one long paragraph where Kwang-dze introduces his own reflections in an unusual style; but the genuineness of the whole, so far as I have observed, has not been called in question.

¶ BOOK XIII. THIEN TÂO.

‘Thien Tâo,’ the first two characters of the first paragraph, and prefixed to the Book as the name of it, are best translated by ‘The Way of Heaven,’ meaning the noiseless spontaneity, which characterises all the operations of nature, proceeding silently, yet ‘perfecting all things.’ As the rulers of the world attain to this same way in their government, and the sages among men attain to it in their teachings, both government and doctrine arrive at a corresponding perfection. ‘The joy of Heaven’ and ‘the joy of Men’ are both realised. There ought to be no purpose or will in the universe. ‘Vacancy, stillness, placidity, tastelessness, quietude, silence, and non-action; this is the perfection of the Tâo and its characteristics.’

Our author dwells especially on doing-nothing or non-action as the subject-matter of the Book. But as the world is full of doing, he endeavours to make a distinction between the Ruling Powers and those subordinate to and employed by them, to whom doing or action and purpose, though still without the thought of self, are necessary; and by this distinction he seems to me to give up the peculiarity of his system, so that some of the critics, especially Aû-yang Hsiû, are obliged to confess that these portions of the Book are unlike the writing of Kwang-dze. Still the antagonism of Tâoism to Confucianism is very apparent [ p. 145 ] throughout. Of the illustrative paragraphs, the seventh, relating the churlish behaviour of Lâo-dze to Confucius, and the way in which he subsequently argues with him and snubs him, is very amusing. The eighth paragraph, relating the interview between Lâo and Shih-khäng Khî, is very strange. The allusions in it to certain incidents and peculiarities in Lâo’s domestic life make us wish that we had fuller accounts of his history; and the way in which he rates his disciple shows him as a master of the language of abuse.

The concluding paragraph about duke Hwan of Khî is interesting, but I can only dimly perceive its bearing on the argument of the Book.

¶ BOOK XIV. THIEN YÜN.

The contrast between the movement of the heavens (  ), and the resting of the earth (

), and the resting of the earth (  ), requires the translation of the characters of the title by ‘The Revolution of Heaven.’ But that idea does not enter largely into the subject-matter of the Book. ‘The whole,’ says Hsüan Ying, ‘consists of eight paragraphs, the first three of which show that under the sky there is nothing which is not dominated by the Tâo, with which the Tîs and the Kings have only to act in accordance; while the last five set forth how the Tâo is not to be found in the material forms and changes of things, but in a spirit-like energy working imperceptibly, developing and controlling all phenomena.’

), requires the translation of the characters of the title by ‘The Revolution of Heaven.’ But that idea does not enter largely into the subject-matter of the Book. ‘The whole,’ says Hsüan Ying, ‘consists of eight paragraphs, the first three of which show that under the sky there is nothing which is not dominated by the Tâo, with which the Tîs and the Kings have only to act in accordance; while the last five set forth how the Tâo is not to be found in the material forms and changes of things, but in a spirit-like energy working imperceptibly, developing and controlling all phenomena.’

I have endeavoured in the notes on the former three paragraphs to make their meaning less obscure and unconnected than it is on a first perusal. The five illustrative paragraphs are, we may assume, all of them factitious, and can hardly be received as genuine productions of Kwang-dze. In the sixth paragraph, or at least a part of it, Lin Hsî-kung acknowledges the hand of the forger, and not less unworthy of credence are in my opinion the rest of it and much of the other four paragraphs. If they may be [ p. 146 ] taken as from the hand of our author himself, he was too much devoted to his own system to hold the balance of judgment evenly between Lâo and Khung.

¶ BOOK XV. KHO Î.

I can think of no better translation for  , the two first characters of the Book, and which appear as its title, than our ‘Ingrained Ideas;’ notions, that is, held as firmly as if they were cut into the substance of the mind. They do not belong to the whole Book, however, but only to the first member of the first paragraph. That paragraph describes six classes of men, only the last of which are the right followers of the Tâo;—the Sages, from the Tâoistic point of view, who again are in the last sentence of the last paragraph identified with ‘the True Men’ described at length in the sixth Book. The fifth member of this first paragraph is interesting as showing how there was a class of Tâoists who cultivated the system with a view to obtain longevity by their practices in the management of the breath; yet our author does not accord to them his full approbation, while at the same time the higher Tâoism appears in the last paragraph, as promoting longevity without the management of the breath. Khû Po-hsiû, in his commentary on Kwang-dze, which was published in 1210, gives Po-î and Shû-khî as instances of the first class spoken of here; Confucius and Mencius, of the second; Î Yin and Fû Yüeh, of the third; Khâo Fû and Hsü Yû, as instances of the fourth. Of the fifth class he gives no example, but that of Phäng Zû mentioned in it.

, the two first characters of the Book, and which appear as its title, than our ‘Ingrained Ideas;’ notions, that is, held as firmly as if they were cut into the substance of the mind. They do not belong to the whole Book, however, but only to the first member of the first paragraph. That paragraph describes six classes of men, only the last of which are the right followers of the Tâo;—the Sages, from the Tâoistic point of view, who again are in the last sentence of the last paragraph identified with ‘the True Men’ described at length in the sixth Book. The fifth member of this first paragraph is interesting as showing how there was a class of Tâoists who cultivated the system with a view to obtain longevity by their practices in the management of the breath; yet our author does not accord to them his full approbation, while at the same time the higher Tâoism appears in the last paragraph, as promoting longevity without the management of the breath. Khû Po-hsiû, in his commentary on Kwang-dze, which was published in 1210, gives Po-î and Shû-khî as instances of the first class spoken of here; Confucius and Mencius, of the second; Î Yin and Fû Yüeh, of the third; Khâo Fû and Hsü Yû, as instances of the fourth. Of the fifth class he gives no example, but that of Phäng Zû mentioned in it.

That which distinguishes the genuine sage, the True Man of Tâoism, is his pure simplicity in pursuing the Way, as it is seen in the operation of Heaven and Earth, and nourishing his spirit accordingly, till there ensues an ethereal amalgamation between his Way and the orderly operation of Heaven. This subject is pursued to the end of the Book. The most remarkable predicate of the spirit so trained is that in the third paragraph,—that ‘Its name is the [ p. 147 ] same as Tî or God;’ on which none of the critics has been able to throw any satisfactory light. Balfour’s version is:—‘Its name is called “One with God;”’ Giles’s, ‘Its name is then “Of God,”’ the ‘then’ being in consequence of his view that the subject is ‘man’s spiritual existence before he is born into the world of mortals.’ My own view of the meaning appears in my version.

Lin Hsî-kung, however, calls the genuineness of the whole Book into question, and thinks it may have proceeded from the same hand as Book XIII. They have certainly one peculiarity in common;-many references to sayings which cannot be traced, but are introduced by the formula of quotation, ‘Therefore, it is said.’

¶ BOOK XVI. SHAN HSING.

‘Rectifying or Correcting the Nature’ is the meaning of the title, and expresses sufficiently well the subject-matter of the Book. It was written to expose the ‘vulgar’ learning of the time as contrary to the principles of the true Tâoism, that learning being, according to Lû Shû-kih, ‘the teachings of Hui-dze and Kung-sun Lung.’ It is to be wished that we had fuller accounts of these. But see in Book XXXIII.

Many of the critics are fond of comparing the Book with the 21st chapter of the 7th Book of Mencius, part i, where that philosopher sets forth ‘Man’s own nature as the most important thing to him, and the source of his true enjoyment,’ which no one can read without admiration. But we have more sympathy with Mencius’s fundamental views about our human nature, than with those of Kwang-dze and his Tâoism. Lin Hsî-kung is rather inclined to doubt the genuineness of the Book. Though he admires its composition, and admits the close and compact sequence of its sentences, there is yet something about it that does not smack of Kwang-dze’s style. Rather there seems to me to underlie it the antagonism of Lâo and Kwang to the learning of the Confucian school. The only characteristic [ p. 148 ] of our author which I miss, is the illustrative stories of which he is generally so profuse. In this the Book agrees with the preceding.

¶ BOOK XVII. KHIÛ SHUI.

Khiû Shui, or ‘Autumn Waters,’ the first two characters of the first paragraph of this Book, are adopted as its title. Its subject, in that paragraph, however, is not so much the waters of autumn, as the greatness of the Tâo in its spontaneity, when it has obtained complete dominion over man. No illustration of the Tâo is so great a favourite with Lâo-dze as water, but he loved to set it forth in its quiet, onward movement, always seeking the lowest place, and always exercising a beneficent influence. But water is here before Kwang-dze in its mightiest volume,—the inundated Ho and the all but boundless magnitude of the ocean; and as he takes occasion from those phenomena to deliver his lessons, I translate the title by ‘The Floods of Autumn.’

To adopt the account of the Book given by Lû Shû-kih:—‘This Book,’ he says, shows how its spontaneity is the greatest characteristic of the Tâo, and the chief thing inculcated in it is that we must not allow the human element to extinguish in our constitution the Heavenly.

‘First, using the illustrations of the Ho and the Sea, our author gives us to see the Five Tîs and the Kings of the Three dynasties as only exhibiting the Tâo, in a small degree, while its great development is not to be found in outward form and appliances so that it cannot be described in words, and it is difficult to find its point of commencement, which indeed appears to be impracticable, while still by doing nothing the human may be united with the Heavenly, and men may bring back their True condition. By means of the conversations between the guardian spirit of the Ho and Zo (the god) of the Sea this subject is exhaustively treated.

‘Next (in paragraph 8), the khwei, the millepede, and other subjects illustrate how the mind is spirit-like in its spontaneity and doing nothing. The case of Confucius (in par. 9) shows the same spontaneity, transforming violence. [ p. 149 ] Kung-sun Lung (in par. 10), refusing to comply with that spontaneity, and seeking victory by his sophistical reasonings, shows his wisdom to be only like the folly of the frog in the well. The remaining three paragraphs bring before us Kwang-dze by the spontaneity of his Tâo, now superior to the allurements of rank; then, like the phœnix flying aloft, as enjoying himself in perfect ease; and finally, as like the fishes, in the happiness of his self-possession.’ Such is a brief outline of this interesting chapter. Many of the critics would expunge the ninth and tenth paragraphs as unworthy of Kwang-dze, the former as misrepresenting Confucius, the latter as extolling himself. I think they may both be allowed to stand as from his pencil.

¶ BOOK XVIII. KIH LO.

The title of this Book, Kih Lo, or ‘Perfect Enjoyment,’ may also be received as describing the subject-matter of it. But the author does not tell us distinctly what he means by ‘Perfect Enjoyment.’ It seems to involve two elements, freedom from trouble and distress, and freedom from the fear of death. What men seek for as their chief good would only be to him burdens. He does not indeed altogether condemn them, but his own quest is the better and more excellent way. His own enjoyment is to be obtained by means of doing nothing; that is, by the Tâo; of which passionless and purposeless action is a chief characteristic; and is at the same time the most effective action, as is illustrated in the operation of heaven and earth.

Such is the substance of the first paragraph. The second is interesting as showing how his principle controlled Kwang-dze on the death of his wife. Paragraph 3 shows us two professors of Tâoism delivered by it from the fear of their own death. Paragraph 4 brings our author before us talking to a skull, and then the skull’s appearance to him in a dream and telling him of the happiness of the state after death. Paragraph 5 is occupied with Confucius and his favourite disciple Yen Hui. It stands by itself, unconnected with the rest of the Book, and its [ p. 150 ] genuineness is denied by some Commentators. The last paragraph, found in an enlarged form in the Books ascribed to Lieh-dze, has as little to do as the fifth with the general theme of the Book, and is a strange anticipation in China of the transrotation or transformation system of Buddhism.

Indeed, after reading this. Book, we cease to wonder that Tâoism and Buddhism should in many practices come so near each other.

¶ BOOK XIX. TÂ SHÄNG.

I have been inclined to translate the title of this Book by ‘The Fuller Understanding of Life,’ with reference to what is said in the second Book on ‘The Nourishment of the Lord of Life.’ There the Life before the mind of the writer is that of the Body; here he extends his view also to the Life of the Spirit. The one subject is not kept, however, with sufficient distinctness apart from the other, and the profusion of illustrations, taken, most of them, from the works of Lieh-dze, is perplexing.

To use the words of Lû Shû-khî:—‘This Book shows how he who would skilfully nourish his life, must maintain his spirit complete, and become one with Heaven. These two ideas preside in it throughout. In par. 2, the words of the Warden Yin show that the spirit kept complete is beyond the reach of harm. In 3, the illustration of the hunchback shows how the will must be maintained free from all confusion. In 4, that of the ferryman shows that to the completeness of the spirit there is required the disregard of life or death. In 5 and 6, the words of Thien Khâi-kih convey a warning against injuring the life by the indulgence of sensual desires. In 7, the sight of a sprite by duke Hwan unsettles his spirit. In 8, the gamecock is trained so as to preserve the spirit unagitated. In 9, we see the man in the water of the cataract resting calmly in his appointed lot. In 10, we have the maker of the bell-stand completing his work as he did in accordance with the mind of Heaven. All these instances show how the [ p. 151 ] spirit is nourished. The reckless charioteering of Tung Yê in par. 11, not stopping when the strength of his horses was exhausted, and the false pretext of Sun Hsiû, clear as at noon-day, are instances of a different kind; while in the skilful Shui, hardly needing the application of his mind, and fully enjoying himself in all things, his movements testify of his harmony with Heaven, and his spiritual completeness.’

¶ BOOK XX. SHAN MÛ.

It requires a little effort to perceive that Shan Mû, the title of this Book, does not belong to it as a whole, but only to the first of its nine paragraphs. That speaks of a large tree which our author once saw on a mountain. The other paragraphs have nothing to do with mountain trees, large or small. As the last Book might be considered to be supplementary to ‘the Nourishment of Life,’ discussed in Book III, so this is taken as having the same relation to Book IV, which treats of ‘Man in the World, associated with other men.’ It shows by its various narratives, some of which are full of interest, how by a strict observance of the principles and lessons of the Tâo a man may preserve his life and be happy, may do the right thing and enjoy himself and obtain the approbation of others in the various circumstances in which he may be placed. The themes both of Books I and IV blend together in it. Paragraph 8 has more the character of an apologue than most of Kwang-dze’s stories.

¶ BOOK XXI, THIEN DZE-FANG.

Thien Dze-fang is merely the name of one of the men who appear in the first paragraph. That he was a historical character is learned from the ‘Plans of the Warring States,’ XIV, art. 6, where we find him at the court of the marquis Wän of Wei (B. C. 424-387), acting as counsellor to that ruler. Thien was his surname; Dze-fang his designation, [ p. 152 ] and Wû-kâi his name. He has nothing to do with any of the paragraphs but the first.

It is not easy to reduce all the narratives or stories in the Book to one category. The fifth, seventh, and eighth, indeed, are generally rejected as spurious, or unworthy of our author; and the sixth and ninth are trivial, though the ninth bears all the marks of his graphic style. Paragraphs 3 and 4 are both long and important. A common idea in them and in 1, 2, and 10, seems to be that the presence and power of the Tâo cannot be communicated by words, and are independent. of outward condition and circumstances.

¶ BOOK XXII. KIH PEI YÛ.

With this Book the Second Part of Kwang-dze’s Essays or Treatises ends. ‘All the Books in it,’ says Lû Shû-kih, ‘show the opposition of Tâoism to the pursuit of knowledge as enjoined in the Confucian and other schools; and this Book may be regarded as the deepest, most vehement, and clearest of them all.’ The concluding sentences of the last paragraph and Lâo-dze’s advice to Confucius in par. 5, to ‘sternly repress his knowledge,’ may be referred to as illustrating the correctness of Lû’s remark.

Book seventeenth is commonly considered to be the most eloquent of Kwang-dze’s Treatises, but this twenty-second Book is not inferior to it in eloquence, and it is more characteristic of his method of argument. The way in which he runs riot in the names with which he personifies the attributes of the Tâo, is a remarkable instance of the subtle manner in which he often brings out his ideas; and in no other Book does he set forth more emphatically what his own idea of the Tâo was, though the student often fails to be certain that he has exactly caught the meaning.

The title, let it be observed, belongs only to the first paragraph. The Kih in it must be taken in the sense of ‘knowledge,’ and not of ‘wisdom.’

[ p. 153 ]

¶ BOOK XXIII. KÄNG-SANG KHÛ.

It is not at all certain that there ever was such a personage as Käng-sang Khû, who gives its name to the Book. In his brief memoir of Kwang-dze, Sze-mâ Khien spells, as we should say, the first character of the surname differently, and for the Käng (  ), employs Khang (

), employs Khang (  ), adding his own opinion, that there was nothing in reality corresponding to the account given of the characters in this and some other Books. They would be therefore the inventions of Kwang-dze, devised by him to serve his purpose in setting forth the teaching of Lâo-dze. It may have been so, but the value of the Book would hardly be thereby affected.

), adding his own opinion, that there was nothing in reality corresponding to the account given of the characters in this and some other Books. They would be therefore the inventions of Kwang-dze, devised by him to serve his purpose in setting forth the teaching of Lâo-dze. It may have been so, but the value of the Book would hardly be thereby affected.

Lû Shû-kih gives the following very brief account of the contents. Borrowing the language of Mencius concerning Yen Hui and two other disciples of Confucius as compared with the sage, he says, ‘Käng-sang Khû had all the members of Lâo-dze, but in small proportions. To outward appearance he was above such as abjure sagehood and put knowledge away, but still he was unable to transform Nan-yung Khû, whom therefore he sent to Lâo-dze; and he announced to him the doctrine of the Tâo that everything was done by doing nothing.’

The reader will see that this is a very incomplete summary of the contents of the Book. We find in it the Tâoistic ideal of the ‘Perfect Man,’ and the discipline both of body and mind through the depths of the system by means of which it is possible for a disciple to become such.

¶ BOOK XXIV. HSÜ WÛ-KWEI.

This Book is named from the first three characters in it, the surname and name of Hsü Wû-kwei, who plays the most important part in the first two paragraphs, and does not further appear. He comes before us as a well-known recluse of Wei, who visits the court to offer his counsels to the marquis of the state. But whether there ever was such [ p. 154 ] a man, or whether he was only a creation of Kwang-dze, we cannot, so far as I know, tell.

Scattered throughout the Book are the lessons so common with our author against sagehood and knowledge, and on the quality of doing nothing and thereby securing the doing of everything. The concluding chapter is one of the finest descriptions in the whole Work of the Tâo and of the Tâoistic idea of Heaven. ‘There are in the Book,’ says Lû Fang, ‘many dark and mysterious expressions. It is not to be read hastily; but the more it is studied, the more flavour will there be found in it.’

¶ BOOK XXV. ZEH-YANG.

This Book is named from the first two characters in it, ‘Zeh-yang,’ which again are the designation of a gentleman of Lû, called Phäng Yang, who comes before us in Khû, seeking for an introduction to the king of that state, with the view, we may suppose, of giving him good counsel. Whether he ever got the introduction which he desired we do not know. The mention of him only serves to bring in three other individuals, all belonging to Khû, and the characters of two of them; but we hear no more of Zeh-yang. The second and third paragraphs are, probably, sequels to the first, but his name does not appear.

The paragraphs from 4 to 9 have more or less interest in themselves; but it is not easy to trace in them any sequence of thought. The tenth and eleventh are more important. The former deals with ‘the Talk of the Hamlets and Villages,’ the common sentiments of men, which, correct and just in themselves, are not to be accepted as a sufficient expression of the Tâo; the latter sets forth how the name Tâo itself is only a metaphorical term, used for the purpose of description; as if the Tâo were a thing, and not capable, therefore, from its material derivation of giving adequate expression to our highest notion of what it is.

‘The Book,’ says Lû Shû-kih, ‘illustrates how the Great Tâo cannot be described by any name; that men ought to [ p. 155 ] stop where they do not really know, and not try to find it in any phenomenon, or in any event or thing. They must forget both speech and silence, and then they may approximate to the idea of the Great Tâo.’

¶ BOOK XXVI. WÂI WÛ.

The first two characters of the first paragraph are again adopted as the title of the Book,—Wâi Wû, ‘External Things;’ and the lesson supposed to be taught in it is that expressed in the first sentence, that the influence of external things on character and condition cannot be determined beforehand. It may be good, it may be evil. Mr. Balfour has translated the two characters by ‘External Advantages.’ Hû Wän-ying interprets them of ‘External Disadvantages.’ The things may in fact be either of these. What seems useless may be productive of the greatest services; and what men deem most advantageous may turn out to be most hurtful to them.

What really belongs to man is the Tâo. That is his own, sufficient for his happiness, and cannot be taken from him, if he prize it and cultivate it. But if he neglect it, and yield to external influences unfavourable to it, he may become bad, and suffer all that is most hateful to him and injurious.

Readers must judge for themselves of the way in which the subject is illustrated in the various paragraphs. Some of the stories are pertinent enough; others are wide of the mark. The second, third, and fourth paragraphs are generally held to be spurious, ‘poor in composition, and not at all to the point.’ If my note on the ‘six faculties of perception’ in par. 9 be correct, we must admit in it a Buddhistic hand, modifying the conceptions of Kwang-dze after he had passed away.

¶ BOOK XXVII. YÜ YEN.

Yü Yen, ‘Metaphorical Words,’ stand at the commencement of the Book, and have been adopted as its name. [ p. 156 ] They might be employed to denote its first paragraph, but are not applicable to the Book as a whole. Nor let the reader expect to find even here any disquisition on the nature of the metaphor as a figure of speech. Translated literally, ‘Yü Yen’ are ‘Lodged Words,’ that is, Ideas that receive their meaning or character from their environment, the narrative or description in which they are deposited.

Kwang-dze wished, I suppose, to give some description of the style in which he himself wrote:—now metaphorical, now abounding in quotations, and throughout moulded by his Tâoistic views. This last seems to be the meaning of his Kih Yen,—literally, ‘Cup, or Goblet, Words,’ that is, words, common as the water constantly supplied in the cup, but all moulded by the Tâoist principle, the element of and from Heaven blended in man’s constitution and that should direct and guide his conduct. The best help in the interpretation of the paragraph is derived from a study of the difficult second Book, as suggested in the notes.

Of the five paragraphs that follow the first, the second relates to the change of views, which, it is said, took place in Confucius; the third, to the change of feeling in Zäng-dze in his poverty and prosperity; the fourth, to changes of character produced in his disciple by the teachings of Tung-kwo Dze-khî; the fifth, to the changes in the appearance of the shadow produced by the ever-changing substance; and the sixth, to the change of spirit and manner produced in Yang Kû by the stern lesson of Lâo-dze.

Various other lessons, more or less appropriate and important, are interspersed.

Some critics argue that this Book must have originally been one with the thirty-second, which was made into two by the insertion between its Parts of the four spurious intervening Books, but this is uncertain and unlikely.

¶ BOOK XXVIII. ZANG WANG.

Zang Wang, explaining the characters as I have done, [ p. 157 ] fairly indicates the subject-matter of the Book. Not that we have a king in every illustration, but the personages adduced are always men of worth, who decline the throne, or gift, or distinction of whatever nature, proffered to them, and feel that they have something better to live for.

A persuasion, however, is widely spread, that this Book and the three that follow are all spurious. The first critic of note to challenge their genuineness was Sû Shih (better known as Sû Tung-pho, A. D. 1046-1101); and now, some of the best editors, such as Lin Hsî-kung, do not admit them into their texts, while others who are not bold enough to exclude them altogether, do not think it worth their while to discuss them seriously. Hû Wän-ying, for instance, says, ‘Their style is poor and mean, and they are, without doubt, forgeries. I will not therefore trouble myself with comments of praise or blame upon them. The reader may accept or reject them at his pleasure.’

But something may be said for them. Sze-mâ Khien seems to have been acquainted with them all. In his short biographical notice of Kwang-dze, he says, ‘He made the Old Fisherman, the Robber Kih, and the Cutting Open Satchels, to defame and calumniate the disciples of Confucius.’ Khien does not indeed mention our present Book along with XXX and XXXI, but it is less open to objection on the ground he mentions than they are. I think if it had stood alone, it would not have been condemned.

¶ BOOK XXIX. TÂO KIH.

It has been seen above that Sze-mâ Khien expressly ascribes the Book called ‘the Robber Kih’ to Kwang-dze. Khien refers also in another place to Kih, adducing the facts of his history in contrast with those about Confucius’ favourite disciple Yen Hui as inexplicable on the supposition of a just and wise Providence. We must conclude therefore that the Book existed in Khien’s time, and that he had read it. On the other hand it has been shown that Confucius could not have been on terms [ p. 158 ] of friendship with Liû-hsiâ Kî, and all that is related of his brother the robber wants substantiation. That such a man ever existed appears to me very doubtful. Are we to put down the whole of the first paragraph then as a jeu d’esprit on the part of Kwang-dze, intended to throw ridicule on Confucius and what our author considered his pedantic ways? It certainly does so, and we are amused to hear the sage outcrowed by the robber.

In the other two paragraphs we have good instances of Kwang-dze’s ‘metaphorical expressions,’ his coinage of names for his personages, more or less ingeniously indicating their characters; but in such cases the element of time or chronology does not enter; and it is the anachronism of the first paragraph which constitutes its chief difficulty.

The name of ‘Robber Kih’ may be said to be a coinage; and that a famous robber was popularly indicated by the name appears from its use by Mencius (III, ii, ch. 10, 3), to explain which the commentators have invented the story of a robber so-called in the time of Hwang-Tî, in the twenty-seventh century B. C.! Was there really such a legend? and did Kwang-dze take advantage of it to apply the name to a notorious and disreputable brother of Liû-hsiâ Kî? Still there remain the anachronisms in the paragraph which have been pointed out. On the whole we must come to a conclusion rather unfavourable to the genuineness of the Book. But it must have been forged at a very early time, and we have no idea by whom.

¶ BOOK XXX. YÜEH KIEN.

We need not suppose that anything ever occurred in Kwang-dze’s experience such as is described here. The whole narrative is metaphorical; and that he himself is made to play the part in it which he describes, only shows how the style of writing in which he indulged was ingrained into the texture of his mind. We do not know that there ever was a ruler of Kâo who indulged in the love of the [ p. 159 ] sword-fight, and kept about him a crowd of vulgar bravoes such as the story describes. We may be assured that our author never wore the bravo’s dress or girt on him the bravo’s sword. The whole is a metaphorical representation of the way in which a besotted ruler might be brought to a feeling of his degradation, and recalled to a sense of his duty and the way in which he might fulfil it. The narrative is full of interest and force. I do not feel any great difficulty in accepting it as the genuine composition of Kwang-dze. Who but himself could have composed it? Was it a good-humoured caricature of him by an able Confucian writer to repay him for the ridicule he was fond of casting on the sage?

¶ BOOK XXXI. YÜ-FÛ.

‘The Old Fisherman’ is the fourth of the Books in the collection of the writings of Kwang-dze to which, since the time of Sû Shih, the epithet of ‘spurious’ has been attached by many. My own opinion, however, has been already intimated that the suspicions of the genuineness of those Books have been entertained on insufficient grounds; and so far as ‘the Old Fisherman’ is concerned, I am glad that it has come down to us, spurious or genuine. There may be a certain coarseness in ‘the Robber Kih,’ which makes us despise Confucius or laugh at him; but the satire in this Book is delicate, and we do not like the sage the less when he walks up the bank from the stream where he has been lectured by the fisherman. The pictures of him and his disciples in the forest, reading and singing on the Apricot Terrace, and of the old man slowly impelling his skiff to the land and then as quietly impelling it away till it is lost among the reeds, are delicious; there is nothing finer of its kind in the volume. What hand but that of Kwang-dze, so light in its touch and yet so strong, both incisive and decisive, could have delineated them?

[ p. 160 ]

¶ BOOK XXXII. LIEH YÜ-KHÂU.

Lieh Yü-khâu, the surname and name of Lieh-dze, with which the first paragraph commences, have become current as the name of the Book, though they have nothing to do with any but that one paragraph, which is found also in the second Book of the writings ascribed to Lieh-dze. There are some variations in the two Texts, but they are so slight that we cannot look on them as proofs that the two passages are narratives of independent origin.

Various difficulties surround the questions of the existence of Lieh-dze, and of the work which bears his name. They will be found distinctly and dispassionately stated and discussed in the 146th chapter of the Catalogue of the Khien-lung Imperial Library. The writers seem to me to make it out that there was such a man, but they do not make it clear when he lived, or how his writings assumed their present form. There is a statement of Liû Hsiang that he lived in the time of duke Ma of Käng (B.C. 627-606); but in that case he must have been earlier than Lâo-dze himself, whom he very frequently quotes. The writers think that Lift’s ‘Mû of Käng’ should be Mû of Lû (B.C. 409-377), which would make him not much anterior to Mencius and Kwang-dze; but this is merely an ingenious conjecture. As to the composition of his chapters, they are evidently not at first hand from Lieh, but by some one of his disciples; whether they were current in Kwang-dze’s days, and be made use of various passages from them, or those passages were Kwang-dze’s originally, and taken from him by the followers of Lieh-dze and added to what fragments they had of their master’s teaching;—these are points which must be left undetermined.

Whether the narrative about Lieh be from Kwang-dze or not, its bearing on his character is not readily apprehended; but, as we study it, we seem to understand that his master Wû-zän condemned him as not having fully attained to the Tâo, but owing his influence with others [ p. 161 ] mainly to the manifestation of his merely human qualities. And this is the lesson which our author keeps before him, more or less distinctly, in all his paragraphs. As Lû Shû-kih. says:—

‘This Book also sets forth Doing Nothing as the essential condition of the Tâo. Lieh-dze, frightened at the respect shown to him by the soup-vendors, and yet by his human doings drawing men to him, disowns the rule of the heavenly; Hwan of Käng, thinking himself different from other men, does not know that Heaven recompenses men according to their employment of the heavenly in them; the resting of the sages in their proper rest shows how the ancients pursued the heavenly and not the human; the one who learned to slay the Dragon, but afterwards did not exercise his skill, begins with the human, but afterwards goes on to the heavenly; in those who do not rest in the heavenly, and perish by the inward war, we see how the small men do not know the secret of the Great Repose; Zhâo Shang, glorying in the carriages which he had acquired, is still farther removed from the heavenly; when Yen Ho shows that the sage, in imparting his instructions, did not follow the example of Heaven in diffusing its benefits, we learn that it is only the Doing Nothing of the True Man which is in agreement with Heaven; the difficulty of knowing the mind of man, and the various methods required to test it, show the readiness with which, when not under the rule of Heaven, it seems to go after what is right, and the greater readiness with which it again revolts from it; in Khao-fû, the Correct, we have one indifferent to the distinctions of rank, and from him we advance to the man who understands the great condition appointed for him, and is a follower of Heaven; then comes he who plays the thief under the chin of the Black Dragon, running the greatest risks on a mere peradventure of success, a resolute opponent of Heaven; and finally we have Kwang-dze despising the ornaments of the sacrificial ox, looking in the same way at the worms beneath and the kites overhead, and regarding himself as quite independent [ p. 162 ] of them, thus giving us an example of the embodiment of the spiritual, and of harmony with Heaven.’

So does this ingenious commentator endeavour to exhibit the one idea in the Book, and show the unity of its different paragraphs.

¶ BOOK XXXIII. THIEN HSIÂ.

The Thien Hsiâ with which this Book commences is in regimen, and cannot be translated, so as to give an adequate idea of the scope of the Book, or even of the first paragraph to which it belongs. The phrase itself means literally ‘under heaven or the sky,’ and is used as a denomination of ‘the kingdom,’ and, even more widely, of the world’ or ‘all men.’ ‘Historical Phases of Tâoist Teaching’ would be nearly descriptive of the subject-matter of the Book; but may be objected to on two grounds:—first, that a chronological method is not observed, and next, that the concluding paragraph can hardly be said to relate to Tâoism at all, but to the sophistical teachers, which abounded in the age of Kwang-dze.

Par. 1 sketches with a light hand the nature of Tâoism and the forms which it assumed from the earliest times to the era of Confucius, as imperfectly represented by him and his school.

Par. 2 introduces us to the system of Mo Tî and his school as an erroneous form of Tâoism, and departing, as it continued, farther and farther from the old model.

Par. 3 deals with a modification of Mohism, advocated by scholars who are hardly heard of elsewhere.

Par. 4 treats of a further modification of this modified Mohism, held by scholars ‘whose Tâo was not the true Tâo, and whose “right” was really “wrong.”’

Par. 5 goes back to the era of Lâo-dze, and mentions him and Kwan Yin, as the men who gave to the system of Tâo a grand development.

Par. 6 sets forth Kwang-dze as following in their steps and going beyond them, the brightest luminary of the system.

[ p. 163 ]

Par. 7 leaves Tâoism, and brings up Hui Shih and other sophists.

Whether the Book should be received as from Kwang-dze himself or from some early editor of his writings is ‘a vexed question.’ If it did come from his pencil, he certainly had a good opinion of himself. It is hard for a foreign student at this distant time to be called on for an opinion on the one side or the other.