[ p. 80 ]

PART II.

¶ 38.

38. 1. (Those who) possessed in highest degree the attributes (of the Tâo) did not (seek) to show them, and therefore they possessed them (in fullest measure). (Those who) possessed in a lower degree those attributes (sought how) not to lose them, and therefore they did not possess them (in fullest measure).

2. (Those who) possessed in the highest degree those attributes did nothing (with a purpose), and had no need to do anything. (Those who) possessed them in a lower degree were (always) doing, and had need to be so doing.

3. (Those who) possessed the highest benevolence were (always seeking) to carry it out, and had no need to be doing so. (Those who) possessed the highest righteousness were (always seeking) to carry it out, and had need to be so doing.

4. (Those who) possessed the highest (sense of) propriety were (always seeking) to show it, and when men did not respond to it, they bared the arm and marched up to them.

5. Thus it was that when the Tâo was lost, its attributes appeared; when its attributes were lost, benevolence appeared; when benevolence was lost, righteousness appeared; and when righteousness was lost, the proprieties appeared.

6. Now propriety is the attenuated form of leal-heartedness and good faith, and is also the commencement of disorder; swift apprehension is

[ p. 81 ]

(only) a flower of the Tâo, and is the beginning of stupidity.

7. Thus it is that the Great man abides by what is solid, and eschews what is flimsy; dwells with the fruit and not with the flower. It is thus that he puts away the one and makes choice of the other.

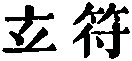

, ‘About the Attributes;’ of Tâo, that is. It is not easy to render teh here by any other English term than ‘virtue,’ and yet there would be a danger of its thus misleading us in the interpretation of the chapter.

, ‘About the Attributes;’ of Tâo, that is. It is not easy to render teh here by any other English term than ‘virtue,’ and yet there would be a danger of its thus misleading us in the interpretation of the chapter.

The ‘virtue’ is the activity or operation of the Tâo, which is supposed to have come out of its absoluteness. Even Han Fei so defines it here,—‘Teh is the meritorious work of the Tâo.’

In par. 5 we evidently have a résumé of the preceding paragraphs, and, as it is historical, I translate them in the past tense; though what took place on the early stage of the world may also be said to go on taking place in the experience of every individual. With some considerable hesitation I have given the subjects in those paragraphs in the concrete, in deference to the authority of Ho-shang Kung and most other commentators. The former says, ‘By “the highest teh” is to be understood the rulers of the greatest antiquity, without name or designation, whose virtue was great, and could not be surpassed.’ Most ingenious, and in accordance with the Tâoistic system, is the manner in which Wû Khäng construes the passage, and I am surprised that it has not been generally accepted. By ‘the higher teh’ he understands ‘the Tâo,’ that which is prior to and above the Teh (  ) by ‘the lower teh,’ benevolence, that which is after and below the Teh; by ‘the higher benevolence,’ the Teh which is above benevolence; by ‘the higher righteousness,’ the benevolence which is above righteousness; and by ‘the higher propriety,’ the righteousness which is above propriety. Certainly in the summation of these four paragraphs which we have in the fifth, the [ p. 82 ] subjects of them would appear to have been in the mind of Lâo-dze as thus defined by Wû.

) by ‘the lower teh,’ benevolence, that which is after and below the Teh; by ‘the higher benevolence,’ the Teh which is above benevolence; by ‘the higher righteousness,’ the benevolence which is above righteousness; and by ‘the higher propriety,’ the righteousness which is above propriety. Certainly in the summation of these four paragraphs which we have in the fifth, the [ p. 82 ] subjects of them would appear to have been in the mind of Lâo-dze as thus defined by Wû.

In the remainder of the chapter he goes on to speak depreciatingly of ceremonies and knowledge, so that the whole chapter must be understood as descriptive of the process of decay and deterioration from the early time in which the Tâo and its attributes swayed the societies of men.

¶ 39.

39. 1. The things which from of old have got the One (the Tâo) are—

Heaven which by it is bright and pure;

Earth rendered thereby firm and sure;

Spirits with powers by it supplied;

Valleys kept full throughout their void

All creatures which through it do live

Princes and kings who from it get

The model which to all they give.

All these are the results of the One (Tâo).

2. If heaven were not thus pure, it soon would rend;

If earth were not thus sure, 'twould break and bend;

Without these powers, the spirits soon would fail;

If not so filled, the drought would parch each vale;

Without that life, creatures would pass away;

Princes and kings, without that moral sway,

However grand and high, would all decay.

3. Thus it is that dignity finds its (firm) root in its (previous) meanness, and what is lofty finds its stability in the lowness (from which it rises). Hence princes and kings call themselves ‘Orphans,’ ‘Men of small virtue,’ and as ‘Carriages without a nave.’ Is not this an acknowledgment that in their considering themselves mean they see the foundation of [ p. 83 ] their dignity? So it is that in the enumeration of the different parts of a carriage we do not come on what makes it answer the ends of a carriage. They do not wish to show themselves elegant-looking as jade, but (prefer) to be coarse-looking as an (ordinary) stone.

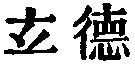

, ‘The Origin of the Law.’ In this title there is a reference to the Law given to all things by the Tâo, as described in the conclusion of chapter 25. And the Tâo affords that law by its passionless, undemonstrative nature, through which in its spontaneity, doing nothing for the sake of doing, it yet does all things.

, ‘The Origin of the Law.’ In this title there is a reference to the Law given to all things by the Tâo, as described in the conclusion of chapter 25. And the Tâo affords that law by its passionless, undemonstrative nature, through which in its spontaneity, doing nothing for the sake of doing, it yet does all things.

The difficulty of translation is in the third paragraph. The way in which princes and kings speak depreciatingly of themselves is adduced as illustrating how they have indeed got the spirit of the Tâo; and I accept the last epithet as given by Ho-shang Kung, ‘naveless’ (  ), instead of

), instead of  (=‘the unworthy’), which is found in Wang Pî, and has been adopted by nearly all subsequent editors. To see its appropriateness here, we have only to refer back to chapter 11, where the thirty spokes, and the nave, empty to receive the axle, are spoken of, and it is shown how the usefulness of the carriage is derived from that emptiness of the nave. This also enables us to give a fair and consistent explanation of the difficult clause which follows, in which also I have followed the text of Ho-shang Kung. For his

(=‘the unworthy’), which is found in Wang Pî, and has been adopted by nearly all subsequent editors. To see its appropriateness here, we have only to refer back to chapter 11, where the thirty spokes, and the nave, empty to receive the axle, are spoken of, and it is shown how the usefulness of the carriage is derived from that emptiness of the nave. This also enables us to give a fair and consistent explanation of the difficult clause which follows, in which also I have followed the text of Ho-shang Kung. For his  , Wang Pî has

, Wang Pî has  , which also is found in a quotation of it by Hwâi-nan Dze; but this need not affect the meaning. In the translation of the clause we are assisted by a somewhat similar illustration about a horse in the twenty-fifth of Kwang-dze’s Books, par. 10.

, which also is found in a quotation of it by Hwâi-nan Dze; but this need not affect the meaning. In the translation of the clause we are assisted by a somewhat similar illustration about a horse in the twenty-fifth of Kwang-dze’s Books, par. 10.

¶ 40.

40. 1. The movement of the Tâo

By contraries proceeds;

And weakness marks the course

Of Tâo’s mighty deeds. [ p. 84 ] 2. All things under heaven sprang from It as existing (and named); that existence sprang from It as non-existent (and not named).

, ‘Dispensing with the Use (of Means);’—with their use, that is, as it appears to us. The subject of the brief chapter is the action of the Tâo by contraries, leading to a result the opposite of what existed previously, and by means which might seem calculated to produce a contrary result.

, ‘Dispensing with the Use (of Means);’—with their use, that is, as it appears to us. The subject of the brief chapter is the action of the Tâo by contraries, leading to a result the opposite of what existed previously, and by means which might seem calculated to produce a contrary result.

In translating par. 2 1 have followed Ziâo Hung, who finds the key to it in ch. 1. Having a name, the Tâo is ‘the Mother of all things;’ having no name, it is ‘the Originator of Heaven and Earth.’ But here is the teaching of Lâo-dze:—‘If Tâo seems to be before God,’ Tâo itself sprang from nothing.

¶ 41.

41. 1. Scholars of the highest class, when they hear about the Tâo, earnestly carry it into practice. Scholars of the middle class, when they have heard about it, seem now to keep it and now to lose it. Scholars of the lowest class, when they have heard about it, laugh greatly at it. If it were not (thus) laughed at, it would not be fit to be the Tâo.

2. Therefore the sentence-makers have thus expressed themselves:—

‘The Tâo, when brightest seen, seems light to lack;

Who progress in it makes, seems drawing back;

Its even way is like a rugged track.

Its highest virtue from the vale doth rise;

Its greatest beauty seems to offend the eyes

And he has most whose lot the least supplies.

Its firmest virtue seems but poor and low;

Its solid truth seems change to undergo;

Its largest square doth yet no corner show

A vessel great, it is the slowest made; p. 85

Loud is its sound, but never word it said;

A semblance great, the shadow of a shade.’

3. The Tâo is hidden, and has no name; but it is the Tâo which is skilful at imparting (to all things what they need) and making them complete.

, ‘Sameness and Difference.’ The chapter is a sequel of the preceding, and may be taken as an illustration of the Tâo’s proceeding by contraries.

, ‘Sameness and Difference.’ The chapter is a sequel of the preceding, and may be taken as an illustration of the Tâo’s proceeding by contraries.

Who the sentence-makers were whose sayings are quoted we cannot tell, but it would have been strange if Lâo-dze had not had a large store of such sentences at his command. The fifth and sixth of those employed by him here are found in Lieh-dze (II, 15 a), spoken by Lâo in reproving Yang Kû, and in VII, 3 a, that heretic appears quoting an utterance of the same kind, with the words,‘ according to an old saying (  )’.

)’.

¶ 42.

42. 1. The Tâo produced One; One produced Two; Two produced Three; Three produced All things. All things leave behind them the Obscurity (out of which they have come), and go forward to embrace the Brightness (into which they have emerged), while they are harmonised by the Breath of Vacancy.

2. What men dislike is to be orphans, to have little virtue, to be as carriages without naves; and yet these are the designations which kings and princes use for themselves. So it is that some things are increased by being diminished, and others are diminished by being increased.

3. What other men (thus) teach, I also teach. The violent and strong do not die their natural death. I will make this the basis of my teaching.

, ‘The Transformations of the Tâo.’ In par. 2 we [ p. 86 ] have the case of the depreciating epithets given to themselves by kings and princes, which we found before in ch. 39, and a similar lesson is drawn from it. Such depreciation leads to exaltation, and the contrary course of self-exaltation leads to abasement. This latter case is stated emphatically in par. 3, and Lâo-dze says that it was the basis of his teaching. So far therefore we have in this chapter a repetition of the lesson that the movement of the Tâo is by contraries,’ and that its weakness is the sure precursor of strength. But the connexion between this lesson and what he says in par. 1 it is difficult to trace. Up to this time at least it has baffled myself. The passage seems to give us a cosmogony. ‘The Tâo produced One.’ We have already seen that the Tâo is ‘The One.’ Are we to understand here that the Tâo, and the One were one and the same? In this case what would be the significance of the

, ‘The Transformations of the Tâo.’ In par. 2 we [ p. 86 ] have the case of the depreciating epithets given to themselves by kings and princes, which we found before in ch. 39, and a similar lesson is drawn from it. Such depreciation leads to exaltation, and the contrary course of self-exaltation leads to abasement. This latter case is stated emphatically in par. 3, and Lâo-dze says that it was the basis of his teaching. So far therefore we have in this chapter a repetition of the lesson that the movement of the Tâo is by contraries,’ and that its weakness is the sure precursor of strength. But the connexion between this lesson and what he says in par. 1 it is difficult to trace. Up to this time at least it has baffled myself. The passage seems to give us a cosmogony. ‘The Tâo produced One.’ We have already seen that the Tâo is ‘The One.’ Are we to understand here that the Tâo, and the One were one and the same? In this case what would be the significance of the  (‘produced’)?—that the Tâo which had been previously ‘non-existent’ now became ‘existent,’ or capable of being named? This seems to be the view of Sze-mâ Kwang (A.D. 1009-1086).

(‘produced’)?—that the Tâo which had been previously ‘non-existent’ now became ‘existent,’ or capable of being named? This seems to be the view of Sze-mâ Kwang (A.D. 1009-1086).

The most singular form which this view assumes is in one of the treatises on our King, attributed to the Tâoist patriarch Lü (  ), that ‘the One is Heaven, which was formed by the congealing of the Tâo.’ According to another treatise, also assigned to the same Lü (

), that ‘the One is Heaven, which was formed by the congealing of the Tâo.’ According to another treatise, also assigned to the same Lü (  ) the One was ‘the primordial ether;’ the Two, ‘the separation of that into its Yin and Yang constituents;’ and the Three, ‘the production of heaven, earth, and man by these.’ In quoting the paragraph Hwâi-nan dze omits

) the One was ‘the primordial ether;’ the Two, ‘the separation of that into its Yin and Yang constituents;’ and the Three, ‘the production of heaven, earth, and man by these.’ In quoting the paragraph Hwâi-nan dze omits  , and commences with

, and commences with  , and his glossarist, Kâo Yû, makes out the One to be the Tâo, the Two to be Spiritual Intelligences (

, and his glossarist, Kâo Yû, makes out the One to be the Tâo, the Two to be Spiritual Intelligences (  ), and the Three to be the Harmonising Breath. From the mention of the Yin and Yang that follows, I believe that Lâo-dze intended by the Two these two qualities or elements in the primordial ether, which would be ‘the One.’ I dare not hazard a guess as to what ‘the Three’ were.

), and the Three to be the Harmonising Breath. From the mention of the Yin and Yang that follows, I believe that Lâo-dze intended by the Two these two qualities or elements in the primordial ether, which would be ‘the One.’ I dare not hazard a guess as to what ‘the Three’ were.

[ p. 87 ]

¶ 43.

43. 1. The softest thing in the world dashes against and overcomes the hardest; that which has no (substantial) existence enters where there is no crevice. I know hereby what advantage belongs to doing nothing (with a purpose).

2. There are few in the world who attain to the teaching without words, and the advantage arising from non-action.

, ‘The Universal Use (of the action in weakness of the Tâo).’ The chapter takes us back to the lines of ch. 40, that

, ‘The Universal Use (of the action in weakness of the Tâo).’ The chapter takes us back to the lines of ch. 40, that

‘Weakness marks the course

Of Tâo’s mighty deeds.’

By ‘the softest thing in the world’ it is agreed that we are to understand ‘water,’ which will wear away the hardest rocks. ‘Dashing against and overcoming’ is a metaphor taken from hunting. Ho-shang Kung says that ‘what has no existence’ is the Tâo; it is better to understand by it the unsubstantial air (  ) which penetrates everywhere, we cannot see how.

) which penetrates everywhere, we cannot see how.

Compare par. 2 with ch. 2, par. 3.

¶ 44.

44. 1. Or fame or life,

Which do you hold more dear?

Or life or wealth,

To which would you adhere?

Keep life and lose those other things;

Keep them and lose your life:—which brings

Sorrow and pain more near?

2. Thus we may see,

Who cleaves to fame

Rejects what is more great;

Who loves large stores

Gives up the richer state. [ p. 88 ] 3. Who is content

Needs fear no shame.

Who knows to stop

Incurs no blame.

From danger free

Long live shall he.

, ‘Cautions.’ The chapter warns men to let nothing come into competition with the value which they set on the Tâo. The Tâo is not named, indeed, but the idea of it was evidently in the writer’s mind.

, ‘Cautions.’ The chapter warns men to let nothing come into competition with the value which they set on the Tâo. The Tâo is not named, indeed, but the idea of it was evidently in the writer’s mind.

The whole chapter rhymes after a somewhat peculiar fashion; familiar enough, however, to one who is acquainted with the old rhymes of the Book of Poetry.

¶ 45.

45. 1. Who thinks his great achievements poor

Shall find his vigour long endure.

Of greatest fulness, deemed a void,

Exhaustion ne’er shall stem the tide.

Do thou what’s straight still crooked deem;

Thy greatest art still stupid seem,

And eloquence a stammering scream.

2. Constant action overcomes cold; being still overcomes heat. Purity and stillness give the correct law to all under heaven.

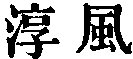

, ‘Great or Overflowing Virtue.’ The chapter is another illustration of the working of the Tâo by contraries. According to Wû Khäng, the action which overcomes cold is that of the Yang element in the developing primordial ether; and the stillness which overcomes heat is that of the contrary Yin element. These may have been in Lâo-dze’s mind, but the statements are so simple as hardly to need any comment. Wû further says that the purity and stillness are descriptive of the condition of non-action.

, ‘Great or Overflowing Virtue.’ The chapter is another illustration of the working of the Tâo by contraries. According to Wû Khäng, the action which overcomes cold is that of the Yang element in the developing primordial ether; and the stillness which overcomes heat is that of the contrary Yin element. These may have been in Lâo-dze’s mind, but the statements are so simple as hardly to need any comment. Wû further says that the purity and stillness are descriptive of the condition of non-action.

¶ 46.

46. 1. When the Tâo prevails in the world, they send back their swift horses to (draw) the dung-carts.

[ p. 89 ]

When the Tâo is disregarded in the world, the war-horses breed in the border lands.

2. There is no guilt greater than to sanction ambition; no calamity greater than to be discontented with one’s lot; no fault greater than the wish to be getting. Therefore the sufficiency of contentment is an enduring and unchanging sufficiency.

, ‘The Moderating of Desire or Ambition.’ The chapter shows how the practice of the Tâo must conduce to contentment and happiness.

, ‘The Moderating of Desire or Ambition.’ The chapter shows how the practice of the Tâo must conduce to contentment and happiness.

In translating par. 1 I have, after Wû Khäng, admitted a  after the

after the  , his chief authority for doing so being that it is so found in a poetical piece by Kang Häng (A. D. 78-139). Kû Hsî also adopted this reading (

, his chief authority for doing so being that it is so found in a poetical piece by Kang Häng (A. D. 78-139). Kû Hsî also adopted this reading (  , XVIII, 7 a). In par. 2 Han Ying has a tempting variation of

, XVIII, 7 a). In par. 2 Han Ying has a tempting variation of  for

for  , but I have not adopted it because the same phrase occurs elsewhere.

, but I have not adopted it because the same phrase occurs elsewhere.

¶ 47.

47. 1. Without going outside his door, one understands (all that takes place) under the sky; without looking out from his window, one sees the Tâo of Heaven. The farther that one goes out (from himself), the less he knows.

2. Therefore the sages got their knowledge without travelling; gave their (right) names to things without seeing them; and accomplished their ends without any purpose of doing so.

, ‘Surveying what is Far-off.’ The chapter is a lesson to men to judge of things according to their internal conviction of similar things in their own experience. Short as the chapter is, it is somewhat mystical. The phrase, ‘The Tâo’ or way of Heaven, occurs in it for the first time; and it is difficult to lay down its precise meaning. Lâo-dze would seem to teach that man is a microcosm; and that, if [ p. 90 ] he understand the movements of his own mind, he can understand the movements of all other minds. There are various readings, of which it is not necessary to speak.

, ‘Surveying what is Far-off.’ The chapter is a lesson to men to judge of things according to their internal conviction of similar things in their own experience. Short as the chapter is, it is somewhat mystical. The phrase, ‘The Tâo’ or way of Heaven, occurs in it for the first time; and it is difficult to lay down its precise meaning. Lâo-dze would seem to teach that man is a microcosm; and that, if [ p. 90 ] he understand the movements of his own mind, he can understand the movements of all other minds. There are various readings, of which it is not necessary to speak.

I have translated par. 2 in the past tense, and perhaps the first should also be translated so. Most of it is found in Han Ying, preceded by ‘formerly’ or ‘anciently.’

¶ 48.

48. 1. He who devotes himself to learning (seeks) from day to day to increase (his knowledge); he who devotes himself to the Tâo (seeks) from day to day to diminish (his doing).

2. He diminishes it and again diminishes it, till he arrives at doing nothing (on purpose). Having arrived at this point of non-action, there is nothing which he does not do.

3. He who gets as his own all under heaven does so by giving himself no trouble (with that end). If one take trouble (with that end), he is not equal to getting as his own all under heaven.

, 'Forgetting Knowledge;-the contrast between Learning and the Tâo. It is only by the Tâo that the world can be won.

, 'Forgetting Knowledge;-the contrast between Learning and the Tâo. It is only by the Tâo that the world can be won.

Ziâo Hung commences his quotations of commentary on this chapter with the following from Kumâragîva on the second par.:—‘He carries on the process of diminishing till there is nothing coarse about him which is not put away. He puts it away till he has forgotten all that was bad in it. He then puts away all that is fine about him. He does so till he has forgotten all that was good in it. But the bad was wrong, and the good is right. Having diminished the wrong, and also diminished the right, the process is carried on till they are both forgotten. Passion and desire are both cut off; and his virtue and the Tâo are in such union that he does nothing; but though he does nothing, he allows all things to do their own doing, and all things are done.’ Such is a Buddhistic view of the passage, not very intelligible, and which I do not endorse.

[ p. 91 ]

In a passage in the ‘Narratives of the School’ (Bk. IX, Art. 2), we have a Confucian view of the passage:—‘Let perspicacity, intelligence, shrewdness, and wisdom be guarded by stupidity, and the service of the possessor will affect the whole world; let them be guarded by complaisance, and his dating and strength will shake the age; let them be guarded by timidity, and his wealth will be all within the four seas; let them be guarded by humility, and there will be what we call the method of “diminishing it, and diminishing it again.”’ But neither do I endorse this.

My own view of the scope of the chapter has been given above in a few words. The greater part of it is found in Kwang-dze.

¶ 49.

49. 1. The sage has no invariable mind of his own; he makes the mind of the people his mind.

2. To those who are good (to me), I am good; and to those who are not good (to me), I am also good;—and thus (all) get to be good. To those who are sincere (with me), I am sincere; and to those who are not sincere (with me), I am also sincere;—and thus (all) get to be sincere.

3. The sage has in the world an appearance of indecision, and keeps his mind in a state of indifference to all. The people all keep their eyes and ears directed to him, and he deals with them all as his children.

, ‘The Quality of Indulgence.’ The chapter shows how that quality enters largely into the dealing of the sage with other men, and exercises over them a transforming influence, dominated as it is in him by the Tâo.

, ‘The Quality of Indulgence.’ The chapter shows how that quality enters largely into the dealing of the sage with other men, and exercises over them a transforming influence, dominated as it is in him by the Tâo.

My version of par. 1 is taken from Dr. Chalmers. A good commentary on it was given by the last emperor but one of the earlier of the two great Sung dynasties, in the period A. D. 1111-1117:—‘The mind of the sage is free from preoccupation and able to receive; still, and able to respond.’

In par. 2 I adopt the reading of to get  (‘to get’) instead of [ p. 92 ] the more common

(‘to get’) instead of [ p. 92 ] the more common  (‘virtue’ or ‘quality’). There is a passage in Han Ying (IX, 3 b, 4 a), the style of which, most readers will probably agree with me in thinking, was moulded on the text before us, though nothing is said of any connexion between it and the saying of Lâo-dze. I must regard it as a sequel to the conversation between Confucius and some of his disciples about the principle (Lâo’s principle) that ‘Injury should be recompensed with Kindness,’ as recorded in the Con. Ana., XIV, 36. We read:—‘Dze-lû said, “When men are good to me, I will also be good to them; when they are not good to me, I will also be not good to them.” Dze-kung said, “When men are good to me, I will also be good to them; when they are not good to me, I will simply lead them on, forwards it may be or backwards.” Yen Hui said, When men are good to me, I will also be good to them when they are not good to me, I will still be good to them.“ The views of the three disciples being thus different, they referred the point to the Master, who said, ”The words of Dze-lû are such as might be expected among the (wild tribes of) the Man and the Mo; those of Dze-kung, such as might be expected among friends; those of Hui, such as might be expected among relatives and near connexions."’ This is all. The Master was still far from Lâo-dze’s standpoint, and that of his own favourite disciple, Yen Hui.

(‘virtue’ or ‘quality’). There is a passage in Han Ying (IX, 3 b, 4 a), the style of which, most readers will probably agree with me in thinking, was moulded on the text before us, though nothing is said of any connexion between it and the saying of Lâo-dze. I must regard it as a sequel to the conversation between Confucius and some of his disciples about the principle (Lâo’s principle) that ‘Injury should be recompensed with Kindness,’ as recorded in the Con. Ana., XIV, 36. We read:—‘Dze-lû said, “When men are good to me, I will also be good to them; when they are not good to me, I will also be not good to them.” Dze-kung said, “When men are good to me, I will also be good to them; when they are not good to me, I will simply lead them on, forwards it may be or backwards.” Yen Hui said, When men are good to me, I will also be good to them when they are not good to me, I will still be good to them.“ The views of the three disciples being thus different, they referred the point to the Master, who said, ”The words of Dze-lû are such as might be expected among the (wild tribes of) the Man and the Mo; those of Dze-kung, such as might be expected among friends; those of Hui, such as might be expected among relatives and near connexions."’ This is all. The Master was still far from Lâo-dze’s standpoint, and that of his own favourite disciple, Yen Hui.

¶ 50.

50. 1. Men come forth and live; they enter (again) and die.

2. Of every ten three are ministers of life (to themselves); and three are ministers of death.

3. There are also three in every ten whose aim is to live, but whose movements tend to the land (or place) of death. And for what reason? Because of their excessive endeavours to perpetuate life.

4. But I have heard that he who is skilful in managing the life entrusted to him for a time travels on the land without having to shun rhinoceros or [ p. 93 ] tiger, and enters a host without having to avoid buff coat or sharp weapon. The rhinoceros finds no place in him into which to thrust its horn, nor the tiger a place in which to fix its claws, nor the weapon a place to admit its point. And for what reason? Because there is in him no place of death.

, ‘The Value set on Life.’ The chapter sets forth the Tâo as an antidote against decay and death.

, ‘The Value set on Life.’ The chapter sets forth the Tâo as an antidote against decay and death.

In par. 1 life is presented to us as intermediate between two non-existences. The words will suggest to many readers those in Job i. 21.

In pars. 2 and 3 I translate the characters  by ‘three in ten,’ instead of by ‘thirteen,’ as Julien and other translators have done. The characters are susceptible of either translation according to the tone in which we read the

by ‘three in ten,’ instead of by ‘thirteen,’ as Julien and other translators have done. The characters are susceptible of either translation according to the tone in which we read the  . They were construed as I have done by Wang Pî; and many of the best commentators have followed in his wake. ‘The ministers of life to themselves’ would be those who eschewed all things, both internal and external, tending to injure health; ‘the ministers of death,’ those who pursued courses likely to cause disease and shorten life; the third three would be those who thought that by mysterious and abnormal courses they could prolong life, but only injured it. Those three classes being thus disposed of, there remains only one in ten rightly using the Tâo, and he is spoken of in the next paragraph.

. They were construed as I have done by Wang Pî; and many of the best commentators have followed in his wake. ‘The ministers of life to themselves’ would be those who eschewed all things, both internal and external, tending to injure health; ‘the ministers of death,’ those who pursued courses likely to cause disease and shorten life; the third three would be those who thought that by mysterious and abnormal courses they could prolong life, but only injured it. Those three classes being thus disposed of, there remains only one in ten rightly using the Tâo, and he is spoken of in the next paragraph.

This par. 4 is easy of translation, and the various readings in it are unimportant, differing in this respect from those in par. 3. But the aim of the author in it is not clear. In ascribing such effects to the possession of the Tâo, is he ‘trifling,’ as Dr. Chalmers thinks? or indulging the play of his poetical fancy? or simply saying that the Tâoist will keep himself out of danger?

¶ 51.

51. 1. All things are produced by the Tâo, and nourished by its outflowing operation. They receive their forms according to the nature of each, and are [ p. 94 ] completed according to the circumstances of their condition. Therefore all things without exception honour the Tâo, and exalt its outflowing operation.

2. This honouring of the Tâo and exalting of its operation is not the result of any ordination, but always a spontaneous tribute.

3. Thus it is that the Tâo produces (all things), nourishes them, brings them to their full growth, nurses them, completes them, matures them, maintains them, and overspreads them.

4. It produces them and makes no claim to the possession of them; it carries them through their processes and does not vaunt its ability in doing so; it brings them to maturity and exercises no control over them;-this is called its mysterious operation.

, ‘The Operation (of the Tâo) in Nourishing Things.’ The subject of the chapter is the quiet passionless operation of the Tâo in nature, in the production and nourishing of things throughout the seasons of the year; a theme dwelt on by Lâo-dze, in II, 4, X, 3, and other places.

, ‘The Operation (of the Tâo) in Nourishing Things.’ The subject of the chapter is the quiet passionless operation of the Tâo in nature, in the production and nourishing of things throughout the seasons of the year; a theme dwelt on by Lâo-dze, in II, 4, X, 3, and other places.

The Tâo is the subject of all the predicates in par. 1, and what seem the subjects in all but the first member should be construed adverbially.

On par. 2 Wû Khäng says that the honour of the Son of Heaven is derived from his appointment by God, and that then the nobility of the feudal princes is derived from him; but in the honour given to the Tâo and the nobility ascribed to its operation, we are not to think of any external ordination. There is a strange reading of two of the members of par. 3 in Wang Pî, viz.  for

for  . This is quoted and predicated of ‘Heaven,’ in the Nestorian Monument of Hsî-an in the eighth century.

. This is quoted and predicated of ‘Heaven,’ in the Nestorian Monument of Hsî-an in the eighth century.

¶ 52.

52. 1. (The Tâo) which originated all under the sky is to be considered as the mother of them all. [ p. 95 ] 2. When the mother is found, we know what her children should be. When one knows that he is his mother’s child, and proceeds to guard (the qualities of) the mother that belong to him, to the end of his life he will be free from all peril.

3. Let him keep his mouth closed, and shut up the portals (of his nostrils), and all his life he will be exempt from laborious exertion. Let him keep his mouth open, and (spend his breath) in the promotion of his affairs, and all his life there will be no safety for him.

4. The perception of what is small is (the secret of) clear-sightedness; the guarding of what is soft and tender is (the secret of) strength.

5. Who uses well his light,

Reverting to its (source so) bright,

Will from his body ward all blight,

And hides the unchanging from men’s sight.

, ‘Returning to the Source.’ The meaning of the chapter is obscure, and the commentators give little help in determining it. As in the preceding chapter, Lâo-dze treats of the operation of the Tâo on material things, he seems in this to go on to the operation of it in man, or how he, with his higher nature, should ever be maintaining it in himself.

, ‘Returning to the Source.’ The meaning of the chapter is obscure, and the commentators give little help in determining it. As in the preceding chapter, Lâo-dze treats of the operation of the Tâo on material things, he seems in this to go on to the operation of it in man, or how he, with his higher nature, should ever be maintaining it in himself.

For the understanding of paragraph 1 we must refer to the first chapter of the treatise, where the Tâo, ‘having no name,’ appears as ‘the Beginning’ or ‘First Cause’ of the world, and then, ‘having a name,’ as its ‘Mother.’ It is the same thing or concept in both of its phases, the ideal or absolute, and the manifestation of it in its passionless doings. The old Jesuit translators render this par. by ‘Mundus principium et causam suam habet in Divino  , seu actione Divinae sapientiae quae dici potest ejus mater.’ So far I may assume that they agreed with me in understanding that the subject of the par. was the Tâo.

, seu actione Divinae sapientiae quae dici potest ejus mater.’ So far I may assume that they agreed with me in understanding that the subject of the par. was the Tâo.

[ p. 96 ]

Par. 2 lays down the law of life for man thus derived from the Tâo. The last clause of it is given by the same translators as equivalent to ‘Unde fit ut post mortem nihil ei timendum sit,’—a meaning which the characters will not bear. But from that clause, and the next par., I am obliged to conclude that even in Lâo-dze’s mind there was the germ of the sublimation of the material frame which issued in the asceticism and life-preserving arts of the later Tâoism.

Par. 3 seems to indicate the method of ‘guarding the mother in man,’ by watching over the breath, the proto-plastic ‘one’ of ch. 42, the ethereal matter out of which all material things were formed. The organs of this breath in man are the mouth and nostrils (nothing else should be understood here by  and

and  ;—see the explanations of the former in the last par. of the fifth of the appendixes to the Yî in vol. xvi, p. 432); and the management of the breath is the mystery of the esoteric Buddhism and Tâoism.

;—see the explanations of the former in the last par. of the fifth of the appendixes to the Yî in vol. xvi, p. 432); and the management of the breath is the mystery of the esoteric Buddhism and Tâoism.

In par. 4 ‘The guarding what is soft’ is derived from the use of ‘the soft lips’ in hiding and preserving the hard and strong teeth.

Par. 5 gives the gist of the chapter:—Man’s always keeping before him the ideal of the Tâo, and, without purpose, simply doing whatever he finds to do; Tâo-like and powerful in all his sphere of action.

I have followed the reading of the last character but one, which is given by Ziâo Hung instead of that found in Ho-shang Kung and Wang Pî.

¶ 53.

53. 1. If I were suddenly to become known, and (put into a position to) conduct (a government) according to the Great Tâo, what I should be most afraid of would be a boastful display.

2. The great Tâo (or way) is very level and easy; but people love the by-ways.

3. Their court(-yards and buildings) shall be well kept, but their fields shall be ill-cultivated, and their granaries very empty. They shall wear elegant and [ p. 97 ] ornamented robes, carry a sharp sword at their girdle, pamper themselves in eating and drinking, and have a superabundance of property and wealth;—such (princes) may be called robbers and boasters. This is contrary to the Tâo surely!

, ‘Increase of Evidence.’ The chapter contrasts government by the Tâo with that conducted in a spirit of ostentation and by oppression.

, ‘Increase of Evidence.’ The chapter contrasts government by the Tâo with that conducted in a spirit of ostentation and by oppression.

In the ‘I’ of paragraph 1 does Lâo-dze speak of himself? I think he does. Wû Khäng understands it of ‘any man,’ i. e. any one in the exercise of government;—which is possible. What is peculiar to my version is the pregnant meaning given to  , common enough in the mouth of Confucius. I have adopted it here because of a passage in Liû Hsiang’s Shwo-wän (XX, 13 b), where Lâo-dze is made to say ‘Excessive is the difficulty of practising the Tâo at the present time,’ adding that the princes of his age would not receive it from him. On the ‘Great Tâo,’ see chapters 25, 34, et al. From the twentieth book of Han Fei (12 b and 13 a) I conclude that he had the whole of this chapter in his copy of our King, but he broke it up, after his fashion, into fragmentary utterances, confused and confounding. He gives also some remarkable various readings, one of which (

, common enough in the mouth of Confucius. I have adopted it here because of a passage in Liû Hsiang’s Shwo-wän (XX, 13 b), where Lâo-dze is made to say ‘Excessive is the difficulty of practising the Tâo at the present time,’ adding that the princes of his age would not receive it from him. On the ‘Great Tâo,’ see chapters 25, 34, et al. From the twentieth book of Han Fei (12 b and 13 a) I conclude that he had the whole of this chapter in his copy of our King, but he broke it up, after his fashion, into fragmentary utterances, confused and confounding. He gives also some remarkable various readings, one of which (  , instead of Ho-shang Kung and Wang Pî’s

, instead of Ho-shang Kung and Wang Pî’s  , character 48) is now generally adopted. The passage is quoted in the Khang-hsî dictionary under

, character 48) is now generally adopted. The passage is quoted in the Khang-hsî dictionary under  with this reading.

with this reading.

¶ 54.

54. 1. What (Tâo’s) skilful planter plants

Can never be uptorn;

What his skilful arms enfold,

From him can ne’er be borne.

Sons shall bring in lengthening line,

Sacrifices to his shrine.

2. Tâo when nursed within one’s self,

His vigour will make true;

[ p. 98 ]

And where the family it rules

What riches will accrue!

The neighbourhood where it prevails

In thriving will abound;

And when 'tis seen throughout the state,

Good fortune will be found.

Employ it the kingdom o’er,

And men thrive all around.

3. In this way the effect will be seen in the person, by the observation of different cases; in the family; in the neighbourhood; in the state; and in the kingdom.

4. How do I know that this effect is sure to hold thus all under the sky? By this (method of observation).

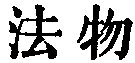

, '‘The Cultivation (of the Tâo), and the Observation (of its Effects).’ The sentiment of the first paragraph is found in the twenty-seventh and other previous chapters,—that the noiseless and imperceptible acting of the Tâo is irresistible in its influence; and this runs through to the end of the chapter with the additional appeal to the influence of its effects. The introduction of the subject of sacrifices, a religious rite, though not presented to the Highest Object, will strike the reader as peculiar in our King.

, '‘The Cultivation (of the Tâo), and the Observation (of its Effects).’ The sentiment of the first paragraph is found in the twenty-seventh and other previous chapters,—that the noiseless and imperceptible acting of the Tâo is irresistible in its influence; and this runs through to the end of the chapter with the additional appeal to the influence of its effects. The introduction of the subject of sacrifices, a religious rite, though not presented to the Highest Object, will strike the reader as peculiar in our King.

The Teh mentioned five times in par. 2 is the ‘virtue’ of the Tâo embodied in the individual, and extending from him in all the spheres of his occupation, and is explained differently by Han Fei according to its application; and his example I have to some extent followed.

The force of pars. 3 and 4 is well given by Ho-shang Kung. On the first clause he says, ‘Take the person of one who cultivates the Tâo, and compare it with that of one who does not cultivate it;—which is in a state of decay? and which is in a state of preservation?’

[ p. 99 ]

¶ 55.

55. 1. He who has in himself abundantly the attributes (of the Tâo) is like an infant. Poisonous insects will not sting him; fierce beasts will not seize him; birds of prey will not strike him.

2. (The infant’s) bones are weak and its sinews soft, but yet its grasp is firm. It knows not yet the union of male and female, and yet its virile member may be excited;—showing the perfection of its physical essence. All day long it will cry without its throat becoming hoarse;—showing the harmony (in its constitution).

3. To him by whom this harmony is known,

(The secret of) the unchanging (Tâo) is shown,

And in the knowledge wisdom finds its throne.

All life-increasing arts to evil turn;

Where the mind makes the vital breath to burn,

(False) is the strength, (and o’er it we should mourn.)

4. When things have become strong, they (then) become old, which may be said to be contrary to the Tâo. Whatever is contrary to the Tâo soon ends.

, ‘The Mysterious Charm;’ meaning, apparently, the entire passivity of the Tâo.

, ‘The Mysterious Charm;’ meaning, apparently, the entire passivity of the Tâo.

With pars. 1 and 2, compare what is said about the infant in chapters 10 and 20, and about the immunity from dangers such as here described of the disciple of the Tâo in ch. 50. My ‘evil’ in the second triplet of par. 3 has been translated by ‘felicity;’ but a reference to the Khang-hsî dictionary will show that the meaning which I give to  is well authorised. It is the only meaning allowable here. The third and fourth

is well authorised. It is the only meaning allowable here. The third and fourth  in this par. appear in Ho-shang Kung’s text as

in this par. appear in Ho-shang Kung’s text as  , and he comments on the clauses accordingly; [ p. 100 ] but

, and he comments on the clauses accordingly; [ p. 100 ] but  is now the received reading. Some light is thrown on this paragraph and the next by an apocryphal conversation attributed to Lâo-dze in Liû Hsiang’s Shwo-wän, X, 4 a.

is now the received reading. Some light is thrown on this paragraph and the next by an apocryphal conversation attributed to Lâo-dze in Liû Hsiang’s Shwo-wän, X, 4 a.

¶ 56.

56. 1. He who knows (the Tâo) does not (care to) speak (about it); he who is (ever ready to) speak about it does not know it.

2. He (who knows it) will keep his mouth shut and close the portals (of his nostrils). He will blunt his sharp points and unravel the complications of things; he will attemper his brightness, and bring himself into agreement with the obscurity (of others). This is called ‘the Mysterious Agreement.’

3. (Such an one) cannot be treated familiarly or distantly; he is beyond all consideration of profit or injury; of nobility or meanness:—he is the noblest man under heaven.

, ‘The Mysterious Excellence.’ The chapter gives us a picture of the man of Tâo, humble and retiring, oblivious of himself and of other men, the noblest man under heaven.

, ‘The Mysterious Excellence.’ The chapter gives us a picture of the man of Tâo, humble and retiring, oblivious of himself and of other men, the noblest man under heaven.

Par. 1 is found in Kwang-dze (XIII, 20 b), not expressly mentioned, as taken from Lâo-dze, but at the end of a string of sentiments, ascribed to ‘the Master,’ some of them, like the two clauses here, no doubt belonging to him, and the others, probably Kwang-dze’s own.

Par. 2 is all found in chapters 4 and 52, excepting the short clause in the conclusion.

¶ 57.

57. 1. A state may be ruled by (measures of) correction; weapons of war maybe used with crafty dexterity; (but) the kingdom is made one’s own (only) by freedom from action and purpose.

2. How do I know that it is so? By these [ p. 101 ] facts:—In the kingdom the multiplication of prohibitive enactments increases the poverty of the people; the more implements to add to their profit that the people have, the greater disorder is there in the state and clan; the more acts of crafty dexterity that men possess, the more do strange contrivances appear; the more display there is of legislation, the more thieves and robbers there are.

3. Therefore a sage has said, ‘I will do nothing (of purpose), and the people will be transformed of themselves; I will be fond of keeping still, and the people will of themselves become correct. I will take no trouble about it, and the people will of themselves become rich; I will manifest no ambition, and the people will of themselves attain to the primitive simplicity.’

, ‘The Genuine Influence.’ The chapter shows how government by the Tâo is alone effective, and of universal application; contrasting it with the failure of other methods.

, ‘The Genuine Influence.’ The chapter shows how government by the Tâo is alone effective, and of universal application; contrasting it with the failure of other methods.

After the ‘weapons of war’ in par. 1, one is tempted to take ‘the sharp implements’ in par. 2 as such weapons, but the meaning which I finally adopted, especially after studying chapters 36 and 80, seems more consonant with Lâo-dze’s scheme of thought. In the last member of the same par., Ho-shang Kung has the strange reading of  , and uses it in his commentary; but the better text of

, and uses it in his commentary; but the better text of  is found both in Hwâi-nan and Sze-mâ Khien, and in Wang Pî.

is found both in Hwâi-nan and Sze-mâ Khien, and in Wang Pî.

We do not know if the writer were quoting any particular sage in par. 3, or referring generally to the sages of the past;—men like the ‘sentence-makers’ of ch. 41.

¶ 58.

58. 1. The government that seems the most unwise,

Oft goodness to the people best supplies;

[ p. 102 ]

That which is meddling, touching everything,

Will work but ill, and disappointment bring.

Misery!—happiness is to be found by its side! Happiness!—misery lurks beneath it! Who knows what either will come to in the end?

2. Shall we then dispense with correction? The (method of) correction shall by a turn become distortion, and the good in it shall by a turn become evil. The delusion of the people (on this point) has indeed subsisted for a long time.

3. Therefore the sage is (like) a square which cuts no one (with its angles); (like) a corner which injures no one (with its sharpness). He is straightforward, but allows himself no license; he is bright, but does not dazzle.

, ‘Transformation according to Circumstances;’ but this title does not throw light on the meaning of the chapter; nor are we helped to an understanding of it by Han Fei, with his additions and comments (XI, 3 b, 4 b), nor by Hwâi-nan with his illustrations (XII, 21 a, b). The difficulty of it is increased by its being separated from the preceding chapter of which it is really the sequel. It contrasts still further government by the Tâo, with that by the method of correction. The sage is the same in both chapters, his character and government both marked by the opposites or contraries which distinguish the procedure of the Tâo, as stated in ch. 40.

, ‘Transformation according to Circumstances;’ but this title does not throw light on the meaning of the chapter; nor are we helped to an understanding of it by Han Fei, with his additions and comments (XI, 3 b, 4 b), nor by Hwâi-nan with his illustrations (XII, 21 a, b). The difficulty of it is increased by its being separated from the preceding chapter of which it is really the sequel. It contrasts still further government by the Tâo, with that by the method of correction. The sage is the same in both chapters, his character and government both marked by the opposites or contraries which distinguish the procedure of the Tâo, as stated in ch. 40.

¶ 59.

59. 1. For regulating the human (in our constitution) and rendering the (proper) service to the heavenly, there is nothing like moderation.

2. It is only by this moderation that there is effected an early return (to man’s normal state). That early return is what I call the repeated accumulation of the attributes (of the Tâo). With that [ p. 103 ] repeated accumulation of those attributes, there comes the subjugation (of every obstacle to such return). Of this subjugation we know not what shall be the limit; and when one knows not what the limit shall be, he may be the ruler of a state.

3. He who possesses the mother of the state may continue long. His case is like that (of the plant) of which we say that its roots are deep and its flower stalks firm:—this is the way to secure that its enduring life shall long be seen.

, ‘Guarding the Tâo.’ The chapter shows how it is the guarding of the Tâo that ensures a continuance of long life, with vigour and success. The abuse of it and other passages in our King helped on, I must believe, the later Tâoist dreams about the elixir vitae and life-preserving pills. The whole of it, with one or two various readings, is found in Han Fei (VI, 4 b-6 a), who speaks twice in his comments of ‘The Book.’

, ‘Guarding the Tâo.’ The chapter shows how it is the guarding of the Tâo that ensures a continuance of long life, with vigour and success. The abuse of it and other passages in our King helped on, I must believe, the later Tâoist dreams about the elixir vitae and life-preserving pills. The whole of it, with one or two various readings, is found in Han Fei (VI, 4 b-6 a), who speaks twice in his comments of ‘The Book.’

Par. 1 has been translated, ‘In governing men and in serving Heaven, there is nothing like moderation.’ But by ‘Heaven’ there is not intended ‘the blue sky’ above us, nor any personal Power above it, but the Tâo embodied in our constitution, the Heavenly element in our nature. The ‘moderation’ is the opposite of what we call ‘living fast,’ ‘burning the candle at both ends.’

In par. 2 I must read  , instead of the more common

, instead of the more common  . I find it in Lû Teh-ming, and that it is not a misprint in him appears from his subjoining that it is pronounced like

. I find it in Lû Teh-ming, and that it is not a misprint in him appears from his subjoining that it is pronounced like  . Its meaning is the same as in

. Its meaning is the same as in  in ch. 52, par. 5. Teh is not ‘virtue’ in our common meaning of the term, but ‘the attributes of the Tâo,’ as almost always with Lâo-dze.

in ch. 52, par. 5. Teh is not ‘virtue’ in our common meaning of the term, but ‘the attributes of the Tâo,’ as almost always with Lâo-dze.

In par. 3 ‘the mother of the state’ is the Tâo as in ch. 1, and especially in ch. 52, par. 1.

¶ 60.

60. 1. Governing a great state is like cooking small fish. [ p. 104 ] 2. Let the kingdom be governed according to the Tâo, and the manes of the departed will not manifest their spiritual energy. It is not that those manes have not that spiritual energy, but it will not be employed to hurt men. It is not that it could not hurt men, but neither does the ruling sage hurt them.

3. When these two do not injuriously affect each other, their good influences converge in the virtue (of the Tâo).

, ‘Occupying the Throne;’ occupying it, that is, according to the Tâo, noiselessly and purposelessly, so that the people enjoy their lives, free from all molestation seen and unseen.

, ‘Occupying the Throne;’ occupying it, that is, according to the Tâo, noiselessly and purposelessly, so that the people enjoy their lives, free from all molestation seen and unseen.

Par. 1. That is, in the most quiet and easy manner. The whole of the chapter is given and commented on by Han Fei (VI, 6a-7b); but very unsatisfactorily.

The more one thinks and reads about the rest of the chapter, the more does he agree with the words of Julien:—‘It presents the frequent recurrence of the same characters, and appears as insignificant as it is unintelligible, if we give to the Chinese characters their ordinary meaning.’—The reader will observe that we have here the second mention of spirits (the manes; Chalmers, ‘the ghosts;’ Julien, les démons). See ch. 39.

Whatever Lâo-dze meant to teach in par. 2, he laid in it a foundation for the superstition of the later and present Tâoism about the spirits of the dead;—such as appeared few years ago in the ‘tail-cutting’ scare.

¶ 61.

61. 1. What makes a great state is its being (like) low-lying, down-flowing (stream);—it becomes the centre to which tend (all the small states) under heaven.

2. (To illustrate from) the case of all females:—the female always overcomes the male by her stillness. Stillness may be considered (a sort of) abasement. [ p. 105 ] 3. Thus it is that a great state, by condescending to small states, gains them for itself; and that small states, by abasing themselves to a great state, win it over to them. In the one case the abasement leads to gaining adherents, in the other case to procuring favour.

4. The great state only wishes to unite men together and nourish them; a small state only wishes to be received by, and to serve, the other. Each gets what it desires, but the great state must learn to abase itself

, ‘The Attribute of Humility;’—a favourite theme with Lâo-dze; and the illustration of it from the low-lying stream to which smaller streams flow is also a favourite subject with him. The language can hardly but recall the words of a greater than Lâo-dze.—‘He that humbleth himself shall be exalted.’

, ‘The Attribute of Humility;’—a favourite theme with Lâo-dze; and the illustration of it from the low-lying stream to which smaller streams flow is also a favourite subject with him. The language can hardly but recall the words of a greater than Lâo-dze.—‘He that humbleth himself shall be exalted.’

¶ 62.

62. 1. Tâo has of all things the most honoured place.

No treasures give good men so rich a grace; Bad men it guards, and doth their ill efface.

2. (Its) admirable words can purchase honour; (its) admirable deeds can raise their performer above others. Even men who are not good are not abandoned by it.

3. Therefore when the sovereign occupies his place as the Son of Heaven, and he has appointed his three ducal ministers, though (a prince) were to send in a round symbol-of-rank large enough to fill both the hands, and that as the precursor of the team of horses (in the court-yard), such an offering would not be equal to (a lesson of) this Tâo, which one might present on his knees.

4. Why was it that the ancients prized this Tâo [ p. 106 ] so much? Was it not because it could be got by seeking for it, and the guilty could escape (from the stain of their guilt) by it? This is the reason why all under heaven consider it the most valuable thing.

, ‘Practising the Tâo.’

, ‘Practising the Tâo.’  , ‘The value set on the Tâo,’ would have been a more appropriate title. The chapter sets forth that value in various manifestations of it.

, ‘The value set on the Tâo,’ would have been a more appropriate title. The chapter sets forth that value in various manifestations of it.

Par. 1. For the meaning of  , see Confucian Analects, III, ch. 13.

, see Confucian Analects, III, ch. 13.

Par. 2. I am obliged to adopt the reading of the first sentence of this paragraph given by Hwâi-nan,  ;—see especially his quotation of it in XVIII, 10 a, as from a superior man, I have not found his reading anywhere else.

;—see especially his quotation of it in XVIII, 10 a, as from a superior man, I have not found his reading anywhere else.

Par. 3 is not easily translated, or explained. See the rules on presenting offerings at the court of a ruler or the king, in vol. xxvii of the ‘Sacred Books of the East,’ p. 84, note 3, and also a narrative in the Zo Kwan under the thirty-third year of duke Hsî.

¶ 63.

63. 1. (It is the way of the Tâo) to act without (thinking of) acting; to conduct affairs without (feeling the) trouble of them; to taste without discerning any flavour; to consider what is small as great, and a few as many; and to recompense injury with kindness.

2. (The master of it) anticipates things that are difficult while they are easy, and does things that would become great while they are small. All difficult things in the world are sure to arise from a previous state in which they were easy, and all great things from one in which they were small. Therefore the sage, while he never does what is great, is able on that account to accomplish the greatest things. [ p. 107 ] 3. He who lightly promises is sure to keep but little faith; he who is continually thinking things easy is sure to find them difficult. Therefore the sage sees difficulty even in what seems easy, and so never has any difficulties.

, ‘Thinking in the Beginning.’ The former of these two characters is commonly misprinted

, ‘Thinking in the Beginning.’ The former of these two characters is commonly misprinted  , and this has led Chalmers to mistranslate them by ‘The Beginning of Grace.’ The chapter sets forth the passionless method of the Tâo, and how the sage accordingly accomplishes his objects easily by forestalling in his measures all difficulties. In par. 1 the clauses are indicative, and not imperative, and therefore we have to supplement the text in translating in some such way, as I have done. They give us a cluster of aphorisms illustrating the procedure of the Tâo ‘by contraries,’ and conclude with one, which is the chief glory of Lâo-dze’s teaching, though I must think that its value is somewhat diminished by the method in which he reaches it. It has not the prominence in the later teaching of Tâoist writers which we should expect, nor is it found (so far as I know) in Kwang-dze, Han Fei, or Hwâi-nan. It is quoted, however, twice by Liû Hsiang;—see my note on par. 2 of ch. 49.

, and this has led Chalmers to mistranslate them by ‘The Beginning of Grace.’ The chapter sets forth the passionless method of the Tâo, and how the sage accordingly accomplishes his objects easily by forestalling in his measures all difficulties. In par. 1 the clauses are indicative, and not imperative, and therefore we have to supplement the text in translating in some such way, as I have done. They give us a cluster of aphorisms illustrating the procedure of the Tâo ‘by contraries,’ and conclude with one, which is the chief glory of Lâo-dze’s teaching, though I must think that its value is somewhat diminished by the method in which he reaches it. It has not the prominence in the later teaching of Tâoist writers which we should expect, nor is it found (so far as I know) in Kwang-dze, Han Fei, or Hwâi-nan. It is quoted, however, twice by Liû Hsiang;—see my note on par. 2 of ch. 49.

It follows from the whole chapter that the Tâoistic ‘doing nothing’ was not an absolute quiescence and inaction, but had a method in it.

¶ 64.

64. 1. That which is at rest is easily kept hold of; before a thing has given indications of its presence, it is easy to take measures against it; that which is brittle is easily broken; that which is very small is easily dispersed. Action should be taken before a thing has made its appearance; order should be secured before disorder has begun.

2. The tree which fills the arms grew from the tiniest sprout; the tower of nine storeys rose from a [ p. 108 ] (small) heap of earth; the journey of a thousand lî commenced with a single step.

3. He who acts (with an ulterior purpose) does harm; he who takes hold of a thing (in the same way) loses his hold. The sage does not act (so), and therefore does no harm; he does not lay hold (so), and therefore does not lose his hold. (But) people in their conduct of affairs are constantly ruining them when they are on the eve of success. If they were careful at the end, as (they should be) at the beginning, they would not so ruin them.

4. Therefore the sage desires what (other men) do not desire, and does not prize things difficult to get; he learns what (other men) do not learn, and turns back to what the multitude of men have passed by. Thus he helps the natural development of all things, and does not dare to act (with an ulterior purpose of his own).

, ‘Guarding the Minute.’ The chapter is a continuation and enlargement of the last. Wû Khäng, indeed, unites the two, blending them together with some ingenious transpositions and omissions, which it is not necessary to discuss. Compare the first part of par. 3 with the last part of par. 1, ch. 29.

, ‘Guarding the Minute.’ The chapter is a continuation and enlargement of the last. Wû Khäng, indeed, unites the two, blending them together with some ingenious transpositions and omissions, which it is not necessary to discuss. Compare the first part of par. 3 with the last part of par. 1, ch. 29.

¶ 65.

65. 1. The ancients who showed their skill in practising the Tâo did so, not to enlighten the people, but rather to make them simple and ignorant.

2. The difficulty in governing the people arises from their having much knowledge. He who (tries to) govern a state by his wisdom is a scourge to it while he who does not (try to) do so is a blessing.

3. He who knows these two things finds in them also his model and rule. Ability to know this [ p. 109 ] model and rule constitutes what we call the mysterious excellence (of a governor). Deep and far-reaching is such mysterious excellence, showing indeed its possessor as opposite to others, but leading them to a great conformity to him.

, ‘Pure, unmixed Excellence.’ The chapter shows the powerful and beneficent influence of the Tâo in government, in contrast with the applications and contrivances of human wisdom. Compare ch. 19. My ‘simple and ignorant’ is taken from Julien. More literally the translation would be ‘to make them stupid.’ My ‘scourge’ in par. 2 is also after Julien’s ‘fléau.’

, ‘Pure, unmixed Excellence.’ The chapter shows the powerful and beneficent influence of the Tâo in government, in contrast with the applications and contrivances of human wisdom. Compare ch. 19. My ‘simple and ignorant’ is taken from Julien. More literally the translation would be ‘to make them stupid.’ My ‘scourge’ in par. 2 is also after Julien’s ‘fléau.’

¶ 66.

66. 1. That whereby the rivers and seas are able to receive the homage and tribute of all the valley streams, is their skill in being lower than they;—it is thus that they are the kings of them all. So it is that the sage (ruler), wishing to be above men, puts himself by his words below them, and, wishing to be before them, places his person behind them.

2. In this way though he has his place above them, men do not feel his weight, nor though he has his place before them, do they feel it an injury to them.

3. Therefore all in the world delight to exalt him and do not weary of him. Because he does not strive, no one finds it possible to strive with him.

, ‘Putting one’s self Last.’ The subject is the power of the Tâo, by its display of humility in attracting men. The subject and the way in which it is illustrated are frequent themes in the King. See chapters 8, 22, 39, 42, 61, et al.

, ‘Putting one’s self Last.’ The subject is the power of the Tâo, by its display of humility in attracting men. The subject and the way in which it is illustrated are frequent themes in the King. See chapters 8, 22, 39, 42, 61, et al.

The last sentence of par. 3 is found also in ch. 22. There seem to be no quotations from the chapter in Han Fei or Hwâi-nan; but Wû Khäng quotes passages from Tung Kung-shû [ p. 110 ] (of the second century B. C.), and Yang Hsiung (B. C. 53-A. D. 18), which seem to show that the phraseology of it was familiar to them. The former says:—‘When one places himself in his qualities below others, his person is above them; when he places them behind those of others, his person is before them;’ the other, ‘Men exalt him who humbles himself below them; and give the precedence to him who puts himself behind them.’

¶ 67.

67. 1. All the world says that, while my Tâo is great, it yet appears to be inferior (to other systems of teaching). Now it is just its greatness that makes it seem to be inferior. If it were like any other (system), for long would its smallness have been known!

2. But I have three precious things which I prize and hold fast. The first is gentleness; the second is economy; and the third is shrinking from taking precedence of others.

3. With that gentleness I can be bold; with that economy I can be liberal; shrinking from taking precedence of others, 1 can become a vessel of the highest honour. Now-a-days they give up gentleness and are all for being bold; economy, and are all for being liberal; the hindmost place, and seek only to be foremost;—(of all which the end is) death.

4. Gentleness is sure to be victorious even in battle, and firmly to maintain its ground. Heaven will save its possessor, by his (very) gentleness protecting him.

, ‘The Three Precious Things.’ This title is taken from par. 2, and suggests to us how the early framer of these titles intended to express by them the subject-matter of their several chapters. The three things are the three distinguishing qualities of the possessor of the Tâo, the [ p. 111 ] three great moral qualities appearing in its followers, the qualities, we may venture to say, of the Tâo itself. The same phrase is now the common designation of Buddhism in China,—the Tri-ratna or Ratna-traya, ‘the Precious Buddha,’ ‘the Precious Law,’ and ‘the Precious Priesthood (or rather Monkhood) or Church;’ appearing also in the ‘Tri-sarana,’ or ‘formula of the Three Refuges,’ what Dr. Eitel calls ‘the most primitive formula fidei of the early Buddhists, introduced before Southern and Northern Buddhism separated.’ I will not introduce the question of whether Buddhism borrowed this designation from Tâoism, after its entrance into China. It is in Buddhism the formula of a peculiar Church or Religion; in Tâoism a rule for the character, or the conduct which the Tâo demands from all men. ‘My Tâo’ in par. 1 is the reading of Wang Pî; Ho-shang Kung’s text is simply a

, ‘The Three Precious Things.’ This title is taken from par. 2, and suggests to us how the early framer of these titles intended to express by them the subject-matter of their several chapters. The three things are the three distinguishing qualities of the possessor of the Tâo, the [ p. 111 ] three great moral qualities appearing in its followers, the qualities, we may venture to say, of the Tâo itself. The same phrase is now the common designation of Buddhism in China,—the Tri-ratna or Ratna-traya, ‘the Precious Buddha,’ ‘the Precious Law,’ and ‘the Precious Priesthood (or rather Monkhood) or Church;’ appearing also in the ‘Tri-sarana,’ or ‘formula of the Three Refuges,’ what Dr. Eitel calls ‘the most primitive formula fidei of the early Buddhists, introduced before Southern and Northern Buddhism separated.’ I will not introduce the question of whether Buddhism borrowed this designation from Tâoism, after its entrance into China. It is in Buddhism the formula of a peculiar Church or Religion; in Tâoism a rule for the character, or the conduct which the Tâo demands from all men. ‘My Tâo’ in par. 1 is the reading of Wang Pî; Ho-shang Kung’s text is simply a  . Wang Pî’s reading is now generally adopted.

. Wang Pî’s reading is now generally adopted.

The concluding sentiment of the chapter is equivalent to the saying of Mencius (VII, ii, IV, 2), ‘If the ruler of a state love benevolence, he will have no enemy under heaven.’ ‘Heaven’ is equivalent to 'the Tâo, 'the course of events,—Providence, as we should say.

¶ 68.

68. He who in (Tâo’s) wars has skill

Assumes no martial port;

He who fights with most good will

To rage makes no resort.

He who vanquishes yet still

Keeps from his foes apart;

He whose hests men most fulfil

Yet humbly plies his art.

Thus we say, 'He ne’er contends,

And therein is his might.’

Thus we say, 'Men’s wills he bends,

That they with him unite.’

Thus we say, 'Like Heaven’s his ends,

No sage of old more bright.’

[ p. 112 ]

, ‘Matching Heaven.’ The chapter describes the work of the practiser of the Tâo as accomplished like that of Heaven, without striving or crying. He appears under the figure of a mailed warrior (

, ‘Matching Heaven.’ The chapter describes the work of the practiser of the Tâo as accomplished like that of Heaven, without striving or crying. He appears under the figure of a mailed warrior (  ) of the ancient chariot. The chapter is a sequel of the preceding, and is joined on to it by Wû Khäng, as is also the next.

) of the ancient chariot. The chapter is a sequel of the preceding, and is joined on to it by Wû Khäng, as is also the next.

¶ 69.

69. 1. A master of the art of war has said, ‘I do not dare to be the host (to commence the war); I prefer to be the guest (to act on the defensive). I do not dare to advance an inch; I prefer to retire a foot.’ This is called marshalling the ranks where there are no ranks; baring the arms (to fight) where there are no arms to bare; grasping the weapon where there is no weapon to grasp; advancing against the enemy where there is no enemy.

2. There is no calamity greater than lightly engaging in war. To do that is near losing (the gentleness) which is so precious. Thus it is that when opposing weapons are (actually) crossed, he who deplores (the situation) conquers.

, ‘The Use of the Mysterious (Tâo).’ Such seems to be the meaning of the title. The chapter teaches that, if war were carried on, or rather avoided, according to the Tâo, the result would be success. Lâo-dze’s own statements appear as so many paradoxes. They are examples of the procedure of the Tâo by ‘contraries,’ or opposites.

, ‘The Use of the Mysterious (Tâo).’ Such seems to be the meaning of the title. The chapter teaches that, if war were carried on, or rather avoided, according to the Tâo, the result would be success. Lâo-dze’s own statements appear as so many paradoxes. They are examples of the procedure of the Tâo by ‘contraries,’ or opposites.

We do not know who the master of the military art referred to was. Perhaps the author only adopted the style of quotation to express his own sentiments.

¶ 70.

70. 1. My words are very easy to know, and very easy to practise; but there is no one in the world who is able to know and able to practise them.

2. There is an originating and all-comprehending [ p. 113 ] (principle) in my words, and an authoritative law for the things (which I enforce). It is because they do not know these, that men do not know me.

3. They who know me are few, and I am on that account (the more) to be prized. It is thus that the sage wears (a poor garb of) hair cloth, while he carries his (signet of) jade in his bosom.

, ‘The Difficulty of being (rightly) Known.’ The Tâo comprehends and rules all Lâo-dze’s teaching, as the members of a clan were all in the loins of their first father (

, ‘The Difficulty of being (rightly) Known.’ The Tâo comprehends and rules all Lâo-dze’s teaching, as the members of a clan were all in the loins of their first father (  ), and continue to look up to him; and the people of a state are all under the direction of their ruler; yet the philosopher had to complain of not being known. Lâo-dze’s principle and rule or ruler was the Tâo. His utterance here is very important. Compare the words of Confucius in the Analects, XIV, ch. 37, et al.

), and continue to look up to him; and the people of a state are all under the direction of their ruler; yet the philosopher had to complain of not being known. Lâo-dze’s principle and rule or ruler was the Tâo. His utterance here is very important. Compare the words of Confucius in the Analects, XIV, ch. 37, et al.

Par. 2 is twice quoted by Hwâi-nan, though his text is not quite the same in both cases.

¶ 71.

71. 1. To know and yet (think) we do not know is the highest (attainment); not to know (and yet think) we do know is a disease.

2. It is simply by being pained at (the thought of) having this disease that we are preserved from it. The sage has not the disease. He knows the pain that would be inseparable from it, and therefore he does not have it.

, ‘The Disease of Knowing.’ Here, again, we have the Tâo working ‘by contraries,’—in the matter of knowledge. Compare par. 1 with Confucius’s account of what knowledge is in the Analects, 11, ch. 17. The par. 1 is found in one place in Hwâi-nan, lengthened out by the addition of particles; but the variation is unimportant. In another place, however, he seems to have had the correct text before him.

, ‘The Disease of Knowing.’ Here, again, we have the Tâo working ‘by contraries,’—in the matter of knowledge. Compare par. 1 with Confucius’s account of what knowledge is in the Analects, 11, ch. 17. The par. 1 is found in one place in Hwâi-nan, lengthened out by the addition of particles; but the variation is unimportant. In another place, however, he seems to have had the correct text before him.

Par. 2 is in Han Fei also lengthened out, but with an [ p. 114 ] important variation (  for

for  ), and I cannot construe his text. His

), and I cannot construe his text. His  is probably a transcriber’s error.

is probably a transcriber’s error.

¶ 72.

72. 1. When the people do not fear what they ought to fear, that which is their great dread will come on them.

2. Let them not thoughtlessly indulge themselves in their ordinary life; let them not act as if weary of what that life depends on.

3. It is by avoiding such indulgence that such weariness does not arise.

4. Therefore the sage knows (these things) of himself, but does not parade (his knowledge); loves, but does not (appear to set a) value on, himself. And thus he puts the latter alternative away and makes choice of the former.

, ‘Loving one’s Self,’ This title is taken from the expression in par. 4; and the object of the chapter seems to be to show how such loving should be manifested, and to enforce the lesson by the example of the ‘sage,’ the true master of the Tâo.

, ‘Loving one’s Self,’ This title is taken from the expression in par. 4; and the object of the chapter seems to be to show how such loving should be manifested, and to enforce the lesson by the example of the ‘sage,’ the true master of the Tâo.