© 2015 Carmelo Martínez

© 2015 Urantia Association of Spain

¶ 1. Introduction

Good evening to those present on this side of the ocean and good afternoon to those on the other side.

The Urantia Book speaks of many things, but at their core, they all refer to the same thing: our destiny to find our Father in Paradise. It also addresses the path we must follow and the realities we will perceive until we reach that absolute Reality.

Today, allow me to stray a bit from the usual and typical script of these presentations and talk about something that will probably be part of our training at some point on this path to the Father, although it may not be a very “spiritual” topic (on the surface). This is the reality in which we are immersed now, the material reality, and which we will undoubtedly encounter in one way or another until we reach Havona. I am going to speak about it from the perspective of today’s science and what The Urantia Book can contribute to its development. Because in revelation, we will not find knowledge that we have not gained for ourselves as humanity—revelation has that limitation—but we can find ideas that help us in that process. The limit, in any case, is that revelation cannot deprive us of the pleasure and satisfaction of discovery.

The first idea we must consider is that the material reality we perceive today is filtered through our five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. All aspects of reality that do not reach us through these senses are not perceptible to us. In fact, our situation is like that of the prisoners in Plato’s myth of the cave, who perceive reality in the shadows it projects on the wall of our senses.

But material reality is much broader. Material reality has manifestations that we are unable to perceive because they don’t impress any of our five senses. Electromagnetic waves are one of the most well-known of these manifestations; otherwise, how could we possibly endure those infamous programs on modern television?

To reach those other aspects we don’t perceive, we can’t use our senses; we must rely on experimentation, deduction, logic, and reason. The door that opens this process for us is curiosity. And the method we use to understand them is scientific.

Throughout its history, science has traveled a path of discovery about material reality, from the sensory perception of what we perceive to the deduction of its deepest constitution. But, as we shall see, and as The Urantia Book suggests, it has not yet reached the end of that path.

In this presentation, I intend to give an overview of how science today thinks matter-energy is constituted, and how this view relates to the same view that The Urantia Book gives us.

This is a topic that can be difficult, so I’ve tried to present it in the most enjoyable way possible.

Let’s get started.

¶ 2. The story

It’s possible that the Nodites—the direct descendants of the rebel members of the Prince’s corporeal team—or their successors, the Andites, once had an advanced culture, society, and civilization, something of an island amidst the natural backwardness of the rest of the planet’s inhabitants, and that there was then a “fall of man,” a regression to less advanced levels. But for the purposes of our Western civilization, the history of knowledge begins with the Greeks.

The Greeks were the first humans on record to wonder what things were made of, what the nature of matter was. They quickly reasoned and deduced that it must be simpler than it seemed, and as early as the 5th century BC, they thought that if we cut matter into ever smaller pieces, there would come a point where we could no longer divide it; we would have reached the smallest constituent of matter. The idea came from Democritus, who called these smaller, invisible, and indivisible pieces “atoms,” which means precisely that, “without division, without parts.” Atoms could be different in size and shape, and their different groupings were what gave matter its distinct properties.

A few decades later, the idea of the four basic elements of matter—water, air, earth, and fire—emerged, and the idea of atoms was ignored or even dismissed. Aristotle, for example, postulated that matter was formed from these four basic elements, but denied the existence of atoms.

We therefore have the idea of the existence of an ultimate and indivisible component of matter (the atom, the elementary particle), and on the other hand, the idea of combining basic elements, elementary particles, to obtain all types of matter. Although the description of the ultimate components and the way they combine to form all types of matter has varied greatly, modern science is based on these same two ideas, now united, to describe the composition of matter and energy.

¶ 3. Modern ideas

Aristotle’s idea of the 4 basic elements remained in force for many centuries, until, approximately 200 years ago, Dalton took up and expanded the ideas of Democritus.

He developed a theory in which all things were composed of invisible and unalterable atoms. He postulated the existence of different types of atoms, one for each constituent element of matter (hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, oxygen, lime, soda, potash, etc.). The atoms of each element were all indivisible (elementary particles), but differed in mass, size, and other physical and chemical properties. In addition to these simple elements, there were compounds formed by the union of atoms of different elements in a fixed proportion and number. For example, he discovered that water was composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, and that hydrogen peroxide was formed by two hydrogen atoms and two oxygen atoms.

Later, in the 19th century, electrical phenomena were discovered and studied, and it was concluded that the atom is not indivisible, but rather is made up of smaller particles carrying electrical charges, some positive and others negative; those of the same sign repel each other, while those of different signs attract each other.

And, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, experiments were conducted that allowed these particles to be identified, and those with a negative sign were called electrons and those with a positive sign were called protons. In these experiments, the mass of these particles was determined, and it was discovered that protons have almost 2,000 times more mass than electrons.

Atoms are no longer indivisible, and the study of how they are formed begins, the development of atomic models begins.

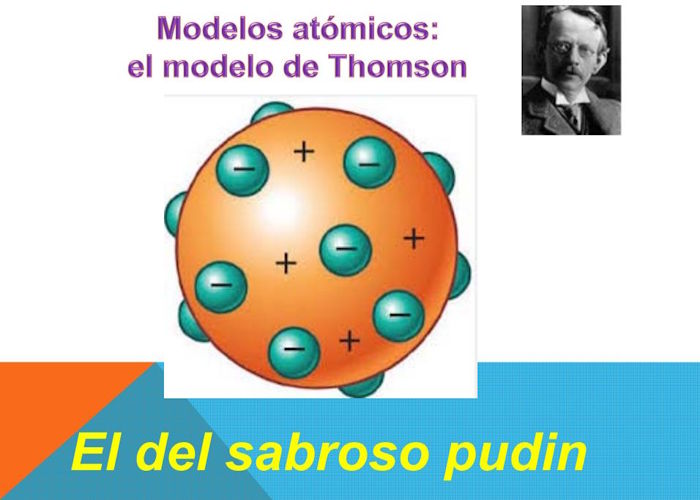

The first and simplest is Thomson’s. When this English physicist presented his model in 1904, protons were not yet known, so he assumed that atoms were made up of a positively charged, spherical mass in which electrons were embedded, like raisins in a pudding. This model was widely accepted because it explained phenomena known until then (for example, electrification by friction or the formation of ions).

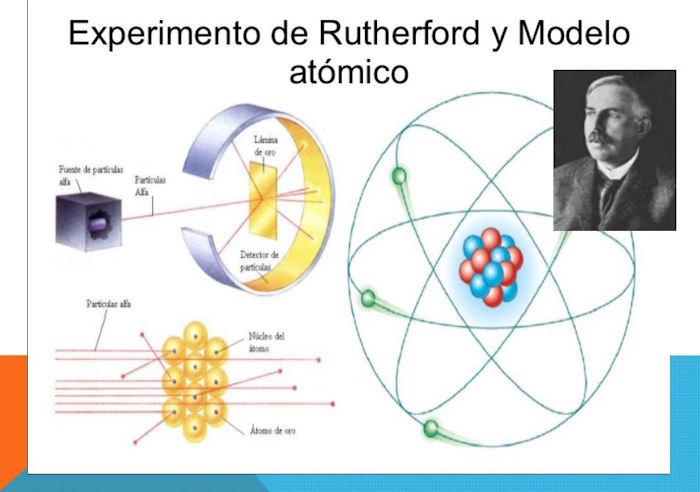

But a few years later, in 1911, Rutherford conducted experiments bombarding a thin gold foil with alpha particles, the results of which could not be explained by Thompson’s “solid” model. He thus proposed the so-called Rutherford model, which postulated that the atom has a central nucleus made up of protons, which contains all the atom’s positive charge and almost all its mass, and that, around and very far from this nucleus, electrons orbit in numbers equal to the protons in the nucleus.

This model had several problems. For example, it didn’t explain how several particles of the same charge could be held together at such close distances without disrupting their formation. Nor could it explain the significant differences in mass between those predicted by his model and those found experimentally. Rutherford himself assumed that there must be other types of particles besides the two described. These particles were discovered in 1933 and, because they had no electrical charge, were called neutrons.

But Rutherford’s model also had other problems. According to the laws of electromagnetism, a charged particle (like the electron) moving in an electric field, that of an atom, emits energy. Electrons, according to this, should eventually lose their energy and fall into the nucleus, and clearly that doesn’t happen.

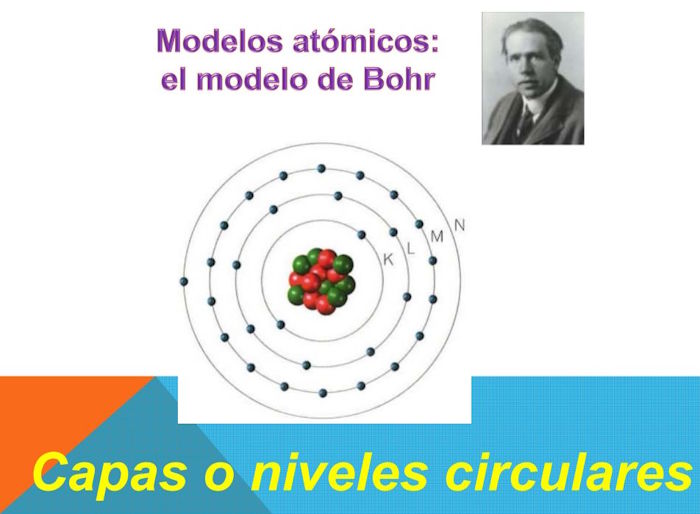

To try to solve these problems, a Danish physicist, Niels Bohr, proposed a new hypothesis about electron orbits in 1913. He postulated that electrons cannot revolve in any orbit, but only in specific ones, and that when they revolve in these orbits, they do not emit energy. A little later, in 1920, this model was refined by adding the concept of electron shells and establishing the number of electrons that “fit” in each shell. And thus, the Rutherford-Bohr model was established, which all high school students of my generation have studied. We were taught, for example, that each element has an atomic number, which is the number of electrons or protons (they are the same number) in the atom of that element, and an atomic mass, which is the sum of the protons and neutrons in its nucleus. We were also taught the concept of isotope: two atoms of the same element (therefore with the same number of protons or electrons), but with different masses (different numbers of protons). A classic example is carbon, which has six electrons in the periphery and six protons in the nucleus, but which comes in two varieties, carbon-12 and carbon-14. The former has six neutrons, and the latter eight.

This model introduces, although still vaguely, some concepts that would later give rise to quantum mechanics, such as the idea of “allowed” orbits and the emission of fixed amounts (quanta) of energy when the electron “jumps” from one shell (of higher energy) to a lower one (of lower energy).

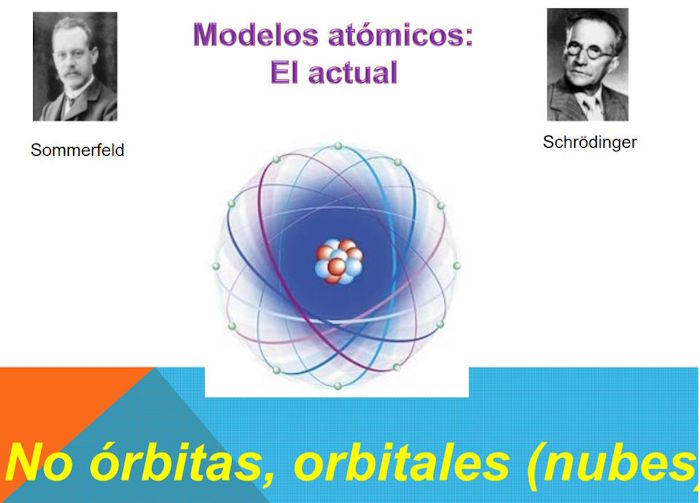

But this model also had problems. To solve them, Sommerfeld postulated that each electron shell (level) split into several subshells and that orbits could be elliptical in addition to being circular. Schrödinger later modified it, incorporating ideas from quantum physics (the wave function). This led to the current atomic model, which, rather than orbiting electrons, describes the periphery of the atom as probability clouds of electron presence.

This model is apparently capable of describing the functioning of those complex structures that atoms have turned out to be, although as the atomic number increases, the structure becomes unmanageably complex, and mathematical models become extraordinarily complicated to the point of being practically useless. The Urantia Book clearly warns of this in paragraph 42:7.10:

“The first twenty-seven atoms, those containing from one to twenty-seven orbital electrons, are more easy of comprehension than the rest. From twenty-eight upward we encounter more and more of the unpredictability of the supposed presence of the Unqualified Absolute… Other influences—physical, electrical, magnetic, and gravitational—also operate to produce variable electronic behavior. Atoms therefore are similar to persons as to predictability. Statisticians may announce laws governing a large number of either atoms or persons but not for a single individual atom or person.” UB 42:7.10

But the discovery of the electron first, then the proton, and later the neutron were only the beginning of an almost endless series of discoveries of the constituent particles of matter. As science acquired more and better experimental tools and higher-power machines, particle after particle began to appear, a whole “jungle” that had to be understood and explained.

But before entering the jungle of elementary particles that make up matter and energy, let’s look at one of the strange results of modern physics, which falls under what is called quantum physics.

¶ 4. Wave-particle duality

Quantum physics presents us with a microscopic world that behaves strangely compared to the macroscopic world, the one within reach of our senses. We are accustomed, for example, to being able to make precise statements about the speed of an object or its position. We understand that a particle is something tiny to which we can assign a clear position in space, and that, conversely, a wave is the opposite of a particle in that it occupies a vast area. But the quantum microcosm is apparently very different from the macrocosm we know.

Since ancient times, it has been believed that light is made up of tiny particles that produce luminous effects when they collide with objects. These particles were thought to move in straight lines, forming light rays. And with this idea in mind, the corpuscular theory of light was developed. This theory could explain a multitude of light phenomena, such as the formation of images through a lens. But there were other phenomena (studied more recently), such as diffraction or interference, that could not be explained. Thus, the wave theory of light was born. Light, in this theory, is a wave like those formed in a pond when a stone is thrown into it.

For years, both theories competed among physicists, but by the end of the 19th century, the wave theory was winning hands down. Maxwell had developed a mathematical model of that theory that seemed to explain all known phenomena. The idea also spread that the end of physics had been reached, that everything had already been explained, and that the most that could be expected were refinements of the formulas. The director of an American patent office even resigned from his position because “there was nothing left to patent.” Poor wretches! What a mess they were in for!

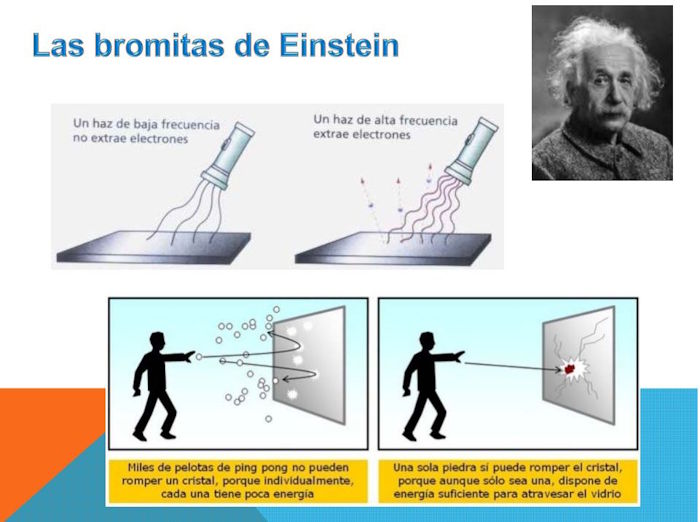

In 1905, Einstein proposed a theory that explained some of the previously observed light phenomena. How was it possible that a wave, when incident under certain conditions on matter, could knock electrons out of it, but only at certain frequencies of light, regardless of their intensity? Einstein, recalling the concept of quantum introduced by Plank a few years earlier, postulated the existence of the photon, the particle of light, and developed his photoelectric theory. The precision with which this theory explains experimental measurements is so spectacular, and the concept of the energy packet (energy quantum) is so innovative that he won the Nobel Prize (curiously, Einstein didn’t win this prize for his theories of relativity, but for postulating the existence of the photon and explaining what it looked like and how it acted). And here the continuity of energy ended; energy is only exchanged in fixed quantities and not continuously. Conventional nineteenth-century physics ended. And light is made up of particles, photons, whose energy is directly proportional to their frequency.

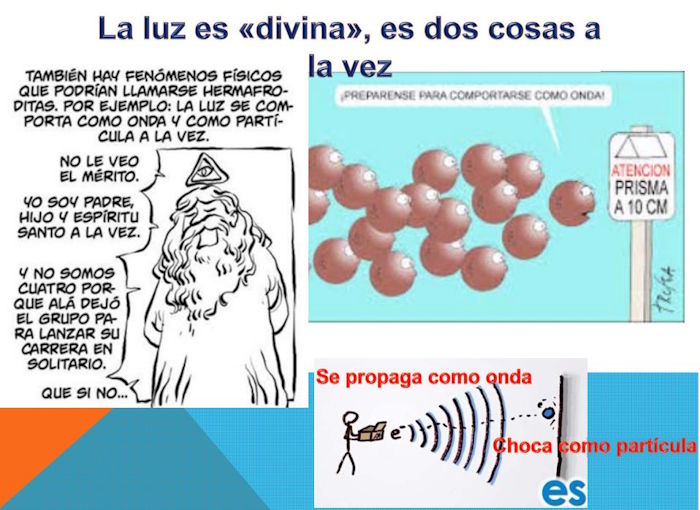

And yet, Maxwell’s formulas remain fully valid: light is a wave (it produces diffraction when passing through a double grating). But it is also a particle (it only extracts electrons from matter when its frequency, and therefore its energy packet, is large enough to knock an electron out of its orbit). What a paradox!

Solution: Light is both; it functions as a wave when it travels and as a discrete particle when it exchanges energy (when it interacts). It’s a contradiction, but it’s what can be deduced from the physical phenomena we know.

Well, okay, you could say, light is a “weird creature,” an exception, perhaps because it is “divine.”

Not at all. In 1924, Louis de Broglie, based on some of his brother’s experiments with X-rays and the work of Einstein and Planck, first proposed the hypothesis of wave-particle duality and associated a wave with electrons! It turned out that electrons, like light, also produced diffraction phenomena when a jet of them was projected through a double grating. In 1929, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for this work.

From then on, physics considered that all particles have an associated wave (they are, in fact, waves), and all waves represent the manifestation of a particle in space. In reality, they are two sides of the same phenomenon. In quantum physics, a particle is not (until it manifests itself through an interaction) at a specific point but in a region that is its wave. A wave is not the manifestation of an influence in a region of space, but of the existence of a particle. In fact, all influences or forces of nature can be formulated in the form of a particle or in the form of a field (a wave).

¶ 5. Particle Physics

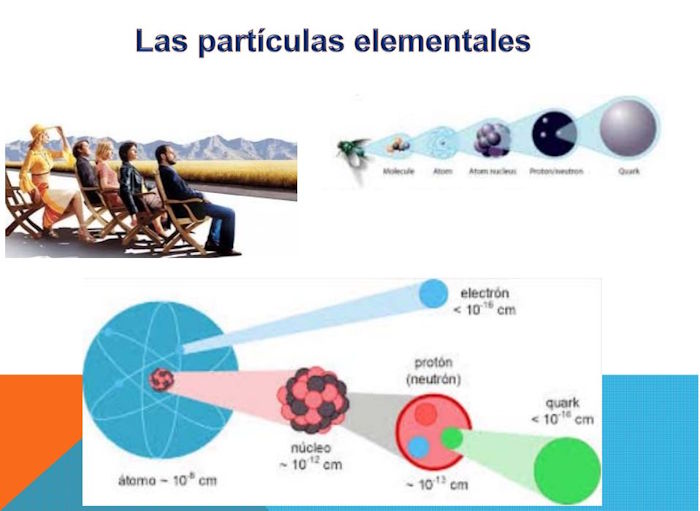

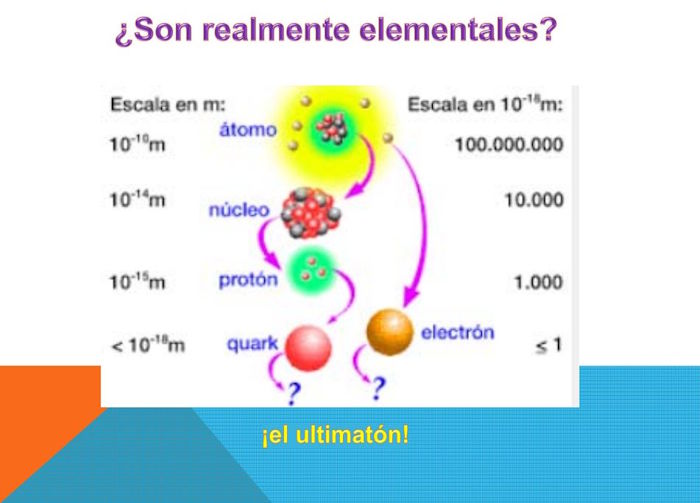

When Dalton revived the idea of atoms, he thought they were elementary particles, that is, not composed of other particles. And so all things were combinations of different types of atoms. Later, electrons, protons, and neutrons were discovered, and they were all thought to be elementary particles. But this is not believed to be the case today either: protons and neutrons are composed of quarks. So, according to current physics, the elementary particles that make up atoms are the quarks in the nucleus, grouped into protons and neutrons, and the electrons (leptons) in the nucleus.

Science has been delving deeper from the atom to the quark to the electron in its search for elementary particles, although most scientists suspect that the end has not yet been reached. All readers of The Urantia Book know that there is at least one step left in the quest toward the elementary particle: the ultimaton.

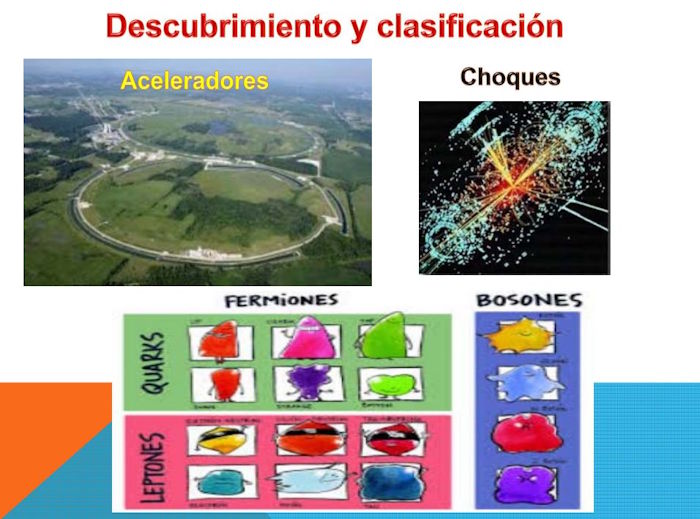

Many particles are known, and more continue to appear in large accelerators. Since humans need to organize and classify in order to understand and draw conclusions, this entire jungle of particles that have been discovered has been classified into two fundamental types: fermions and bosons. Fermions are the particles that make up matter, and bosons are the particles that move the world, which represent the forces of nature. Photons, for example, are bosons; electrons are fermions. This first classification is not as arbitrary as one might suppose. There is something in the essence of particles of both types that differentiates them and determines their behavior. We will not go into these details, nor will I describe all known particles; only the basic ones that, under stable conditions, form matter and that can help us connect modern physics with what The Urantia Book says, which is ultimately one of the objectives of this presentation.

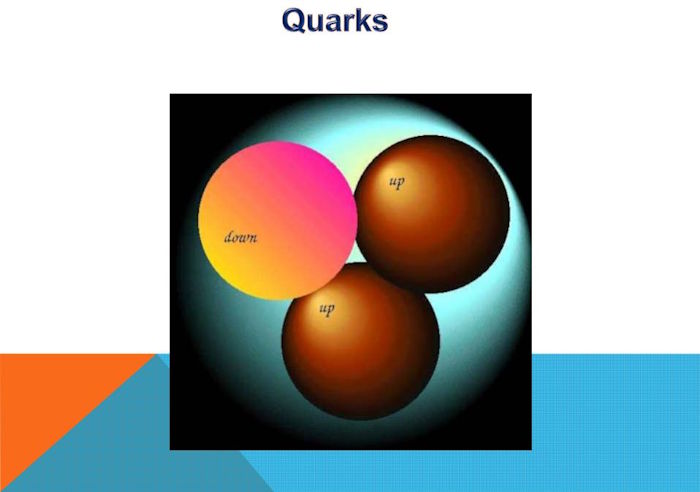

Matter is therefore composed of atoms that have a periphery of electrons and a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons. It has been found that both protons and neutrons are composed of three quarks. Protons consist of two up quarks and one down quark, and neutrons consist of two down quarks and one up quark. The nucleus, despite the natural repulsion of protons, positively charged particles, is stable thanks to the neutrons. This stability of the nucleus is achieved by modifying the type of its component quarks at dizzying frequencies, which converts protons into neutrons and vice versa. Simply put, what a proton loses to become a neutron, a neutron absorbs to become a proton. This is the phenomenon described in The Urantia Book in section 8 of Paper 42, especially paragraphs 3 and 4.

And so we come to what we might call the “building block” of matter. We have seen how, starting from “bricks”—elementary particles—through combinations and recombinations and according to “blueprints” that describe their design, all matter is constructed.

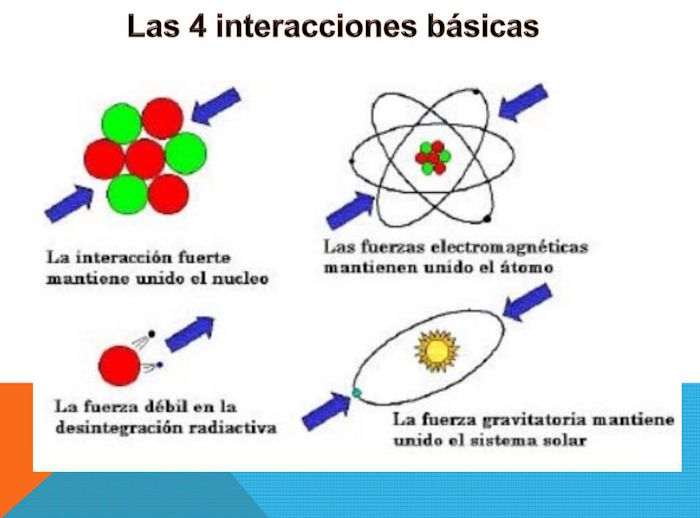

But with this, we’ve only described the building blocks that make up things. We’re missing the concrete that unites them (that separates them!). Physics calls this concrete interactions, and asserts that everything that happens with matter-energy can be explained with just four:

- The interaction of gravity.

- Electromagnetic interaction.

- The weak nuclear interaction.

- The strong nuclear interaction.

The gravity physics speaks of is what the book calls linear. The others—circular or physical gravity, mental gravity, spiritual gravity, and personality gravity, all described in section 3 of document 12 of the book—apparently fall outside the scope of physics and are completely unknown to it.

The first two are the most recognizable. Who doesn’t know what gravity, or electricity, and Hertzian waves are? The other two are much more alien to our experience. The strong nuclear force is responsible for holding the nuclei of atoms together without breaking apart due to the repulsion between protons. The weak nuclear force is what causes some more unstable isotopes to transform into more stable ones, for example, carbon-14 into carbon-12. It is responsible for ensuring that the structure and size of atoms remain within certain ranges, which ultimately define the stability of matter-energy.

Each of these can be associated with a field, for example, the gravitational or magnetic field, but also with a particle, which is the one that produces the effect when it interacts with a lepton (e.g., an electron) or a quark. The particles that transmit the four interactions are called bosons. The field associated with each boson is equivalent to the field associated with each fermion, but just as in the latter, this field (actually, the ripples of that field, the waves) represented the probability of finding the corresponding fermion at a point in the field, in bosons it represents the “strength” with which the interaction acts at that point. But fundamentally, it’s the same; interactions are produced by collisions between bosons and fermions, and the intensity of that interaction is statistically (as a statistical mean) the probability of finding the boson at that point.

Each of these acts on a characteristic of the particle. Gravity on mass, electromagnetic force on electric charge, weak nuclear force on a characteristic they’ve called “flavor charge,” and strong force on another characteristic called “color charge.” And these are four of the only five characteristics that determine the behavior, the interactions, of the particle. The fifth is spin, which determines whether the particle is a fermion or a boson.

And so, everything (the bricks and the concrete that binds them together) can be represented by waves (fields) associated with particles.

Let’s summarize the edifice of matter in a table. The first three columns on the left are the building blocks: the fermions. In reality, only the first form particles and stable matter; they are called first-generation particles. The other two columns are those of the second and third generations, and the particles they form are unstable and decay into other first-generation particles. The fourth column is the concrete: the bosons. There is a fifth column (a curious coincidence of name!, although without any political connotation) containing the now-famous Higgs boson, which I’ll discuss shortly.

The other bosons (the gauge bosons) are the photon for the electromagnetic interaction (light is a special manifestation of the electromagnetic field), the gluon for the strong nuclear interaction, and the and bosons for the weak nuclear interaction. Hey, you might say, the gravity boson is missing! And that’s true, but it turns out to be a theoretical particle, for the moment; some call it a graviton, but it hasn’t been found yet, and one might think that it might never be found.

Humans have a great desire for unification. We like to explain everything with a single set of laws. Physics has managed to explain three of the four interactions with a single set of laws; and this theory has been called the “Standard Model.” It manages to describe the relationships between three of the four basic interactions and the elementary particles. But to date, gravity has not been integrated into a single unified theory; if it were, this theory could be called The Theory of Everything. But it has resisted, perhaps because it is not possible on the current foundations of physics, those underlying the Standard Model. Some physicists, faced with these difficulties, have sought different foundations and have developed, halfway, a String Theory. I say halfway because they also seem to have reached an impasse, among other reasons because, in developing it, mathematical tools that do not yet exist would be needed.

Could the hypothesis that none of the above particles are, in fact, elementary, and the assumption that they are all made up of a single, truly elementary particle, unknown until now, be the solution to these impasses? Who knows. But perhaps it would be good for particle physicists to read what the book says about the ultimaton. Although it’s quite possible that they’ve already done so and that, in some laboratory deeply buried in some remote desert, work along these lines is already underway. Who knows how far they’ve come!

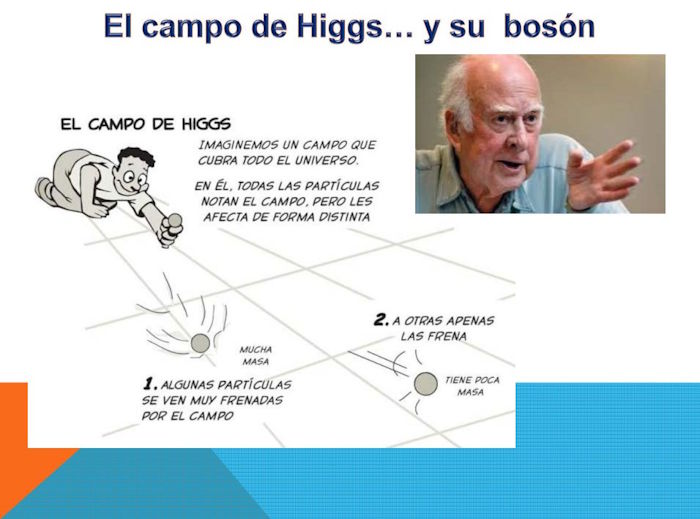

¶ 6. The Higgs boson

I have intentionally wanted to dedicate a section to the already famous Higgs boson, not because it has anything special from a physical point of view, but for other reasons that will appear in this section.

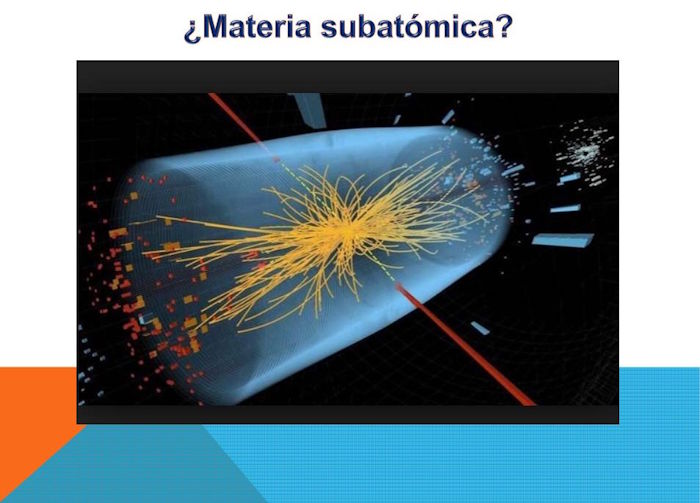

This particle has been predicted and described by the Standard Model from the beginning, although it had not been possible to find it, and therefore confirm it experimentally, until recently (2012).

In the Standard Model, the behavior of all particles is described by attributing certain characteristics to them, as I mentioned earlier. One of these characteristics is mass. Physicists wondered why particles had the mass they did. To explain this, they thought that all of reality was bathed in a field, in which all particles move. This idea was initially proposed by the British physicist Peter Ware Higgs (Newcastle, 1929), which is why it is called the Higgs field. Since every field is the manifestation of a particle, and every particle has an associated field, the formulation of the Higgs field immediately leads to the postulate of the existence of an associated particle. This particle was postulated to be a boson and was named after the field, the Higgs boson. This theoretical idea has been verified experimentally at CERN’s LHC accelerator (although some physicists still question the results of these experiments and even the very existence of the particle).

Particles acquire their mass through their motion within the Higgs field (which permeates everything). Apparently, the resistance the field opposes to the motion of different particles is not the same for all of them. Just as there are more “seaworthy” and less “seaworthy” vessels at sea, there are more “massive” and less “massive” particles. The Higgs field offers less resistance to the most “massive” particles, which gives them less mass. The greater the resistance of the Higgs field, the more massive the particle will be.

This ability to endow particles with mass is what led journalists, some of whom have a pathological tendency toward sensationalism, to call the Higgs boson the God particle. Higgs himself, an atheist, opposed this designation. There is nothing special about the Higgs field and particle, apart from their specific role in the Standard Model.

On the other hand, some readers of The Urantia Book have thought that the Higgs boson is the ultimaton, but I don’t believe this. The ultimaton is a particle that doesn’t react to linear gravity and is therefore massless. However, the Higgs boson has a mass predicted by the Standard Model and verified experimentally.

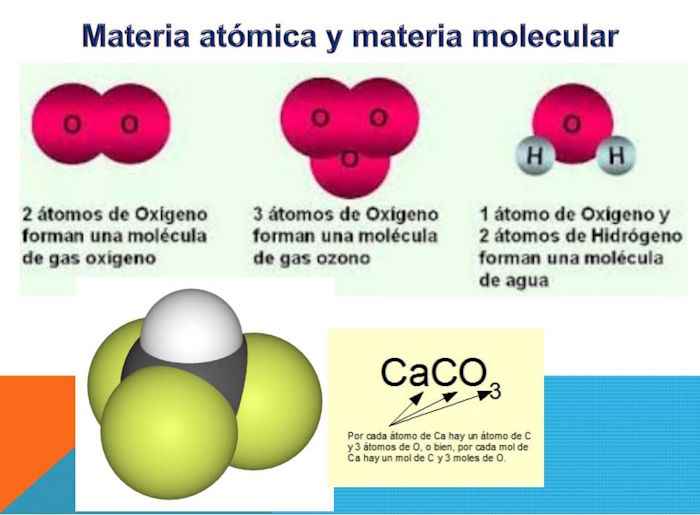

¶ 7. Classification of matter

This section has the same title as section 3 of Paper 42 of The Urantia Book because I intend to explain what today’s physics understands to be “the ten great divisions of matter.”

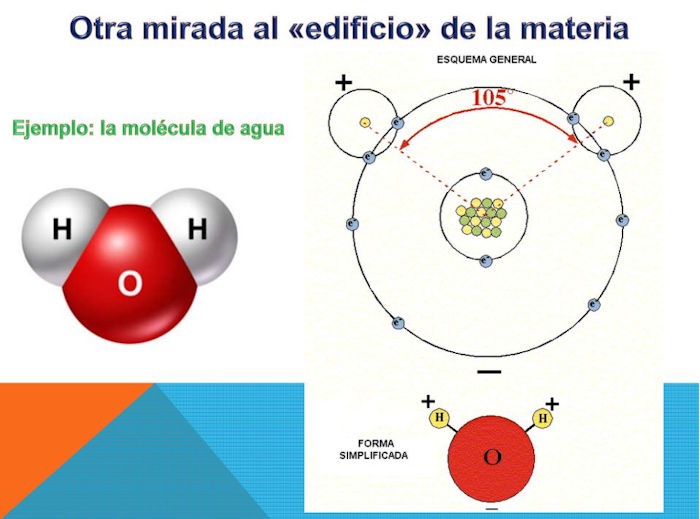

I’ll start with 7 Atomic Matter and 8 The Molecular Stage of Matter. All ordinary things in the world are “molecular matter,” molecules, and molecules are compounds of atoms, of “atomic matter,” type 7 in the textbook’s classification. Some molecules have only atoms of the same element, since atoms of elements (such as oxygen or hydrogen) never appear alone in their stable state; they always group together to form molecules. For example, the stable free oxygen we find in nature is composed of molecules with two atoms, O2. We can also find ozone, which is an allotropic variety of the element oxygen, whose molecules have three oxygen atoms, O3. But most of the molecules of matter we observe in the world are composed of atoms of different elements. The most classic and well-known is the water molecule, H2O. But many of the rocks and other materials that abound in our world are calcium carbonates, CaCO3 : one atom of calcium, one of carbon and 3 of oxygen.

This is the form taken by what the book calls “the molecular stage of matter.” It’s a form “relatively stable under normal conditions,” and that’s precisely why it’s what makes up all the things we know.

But let’s look deeper. Molecules are made up of atoms, which have a nucleus made up of protons and neutrons and a periphery of electrons grouped in several shells at different distances from the nucleus. But the atom is mostly empty space. To give us an idea of how empty an atom is, imagine that if the nucleus were the size of an orange, the atom would have a diameter of about eight hundred meters, and inside it would only have thin concentric clouds of electrons, the first of which would be quite far from the nucleus (about half the distance from the outside). This is why we could say that matter does not exist! Because 99.99999 % of the atom is empty space. However, we perceive matter as something compact because electromagnetic interaction does not allow atoms, despite being almost empty, to fit inside each other; When the outer clouds of two atoms approach each other, there is a force of electrical repulsion that prevents them from merging in the same space and thus makes them act as if they were actually solid balls.

Matter is thus made up of buildings, which are atoms grouped into molecules. The architects who designed these buildings are the Architects of the Master Universe. The matter they are composed of (the building blocks, i.e., quarks and electrons) and the laws of their operation (the concrete that binds them together, i.e., the four basic interactions) are their work (you already know that the Father is retired and delegates everything he can to others).

The architects of the master universe were excellent designers of matter. They designed a single elementary particle that, combined in different ways, would form all the component particles of matter, the building blocks of buildings. They then designed four basic forces to organize the “architecture of matter,” concrete. The strong nuclear force allows the formation of nuclei composed of protons (mutually repulsive) and neutrons. Then, for the most delicate phase of the architecture of the atomic building, they designed the weak nuclear force (and thus atoms are built as they are), which, together with the electromagnetic force, organizes the layers of electron clouds and the balance between protons and neutrons. If one attempts to deviate from this balance, the resulting building is unstable and eventually disintegrates into other smaller but stable buildings. And thus the properties of matter “depends on the revolutionary rates of its component members, the number and size of the revolving members, their distance from the nuclear body or the space content of matter, as well as on the presence of certain forces as yet undiscovered on Urantia” UB 42:3.1.

Electromagnetic interaction makes, among other things, matter, which is mostly empty, appear compact, thus allowing the world to be what we see it to be. Gravitational interaction, on the other hand, causes matter to clump together as it does, allowing planets and other bodies in space to enter stable orbits suitable for human habitation.

But according to these laws, there are other possible buildings, some of which are like the previous ones, but half-built (or half-destroyed, depending on how you look at it). These buildings don’t appear under normal conditions, and some are so special that they can only occur under the extreme conditions of certain stars. And with that, we move on to the rest of the classification types in Section 3 of Document 42.

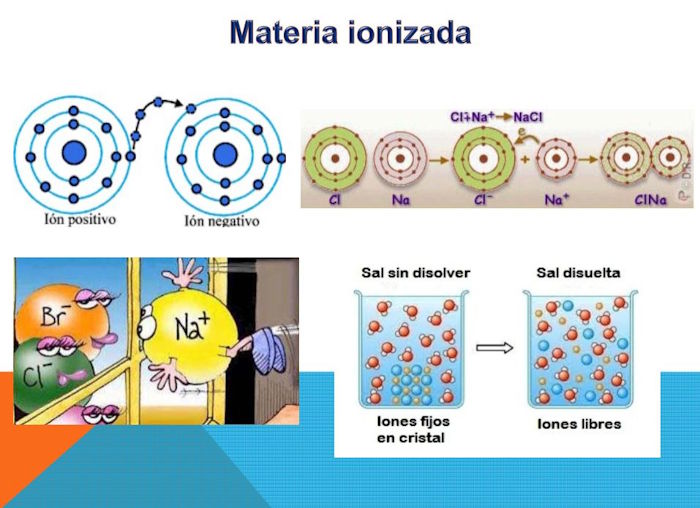

Of all of them, type 6 Ionized Matter is well known to our physics; these are atoms that have lost, for whatever reason, an electron from the outermost cloud, thus becoming positively charged, or that have gained an additional electron in their outer shell, thus becoming negatively charged. A very common and well-known case is that of common salt, which is made up of molecules that have a sodium atom (weakly) bonded to a chlorine atom, NaCl. The bond is quite weak and can be broken fairly easily; it is not a “church marriage,” but rather a friends-with-benefits relationship. When mixed with water, the water molecules separate both elements, but the chlorine atom keeps the electron from the sodium atom that united them (it keeps the rosary from the mother who had given it the now-painful sodium to strengthen the relationship), an electron that this sodium atom loses. Thus, Na+ and Cl- ions are formed.

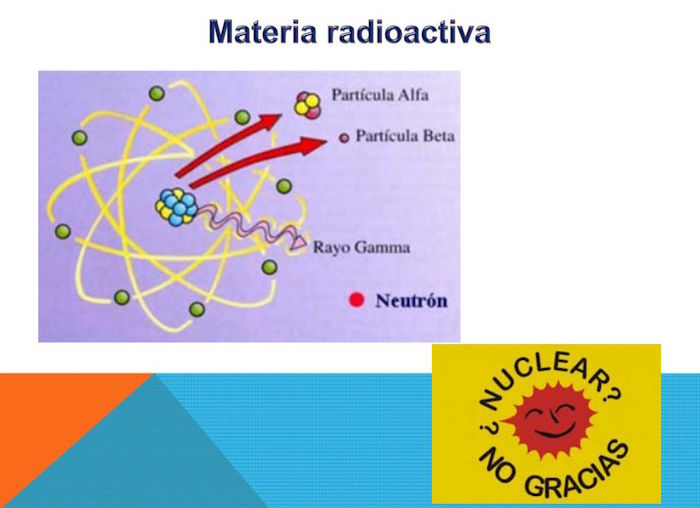

Type 9 Radioactive Matter is also well-known, to the misfortune of humanity. There are some atomic structures whose edifices are unbalanced or too large. This is sometimes the result of natural processes, believed to occur, for example, in a supernova explosion. Naturally occurring radioactive elements are atoms with high atomic mass, many protons and neutrons. The weak nuclear force is unable to sustain such large structures, and they decompose into smaller ones, thereby emitting radiation of different types (which are nothing more than particles or aggregates of particles).

The rest of the types are not commonly described in physics, so I’ll interpret them as what I understand them to mean. For example, type 5 Smashed Atoms must be compounds of protons and neutrons similar to the nuclei of atoms, although perhaps without the balance between the two particles that nuclei have. An example could be alpha particles, which are helium nuclei (two protons and two neutrons).

The name Type 4, Subatomic Matter, seems to be a clue as to what it is. They may be incomplete atomic structures, perhaps with highly unstable nuclei due to the lack of the correct ratio of protons and neutrons, perhaps including some electron shells, though not quite completing those of the equivalent atom. What difference does it make with Type 5? I couldn’t say.

Type 3, Electronic Matter, is easier to identify; it consists of electrons, protons, neutrons, and other similar particles that have not grouped together to form atomic nuclei or atoms. This type, like the two preceding and subsequent types, can only occur under extreme conditions, in suns at some stage of their evolution, or in seemingly empty space.

Type 2 Subelectronic Matter seems to point to what physics calls quarks and other similar particles that make up electronic particles.

Type 1 ultimatonic matter is completely unknown to our physics, at least for now. These are ultimatons that are free and do not combine to form other particles.

And I’ve left Type 10 Crumbling Matter for last, which can be compared to the pile of rubble left by collapsed buildings. Matter is no longer almost entirely empty space, as we saw when discussing atoms. The enormous pressures of dead suns have compressed the atoms so much that they’ve crushed them down to practically no empty space left, and almost all the particles have decayed into their original ultimatons, which are now packed tightly together.

¶ 8. Ultimatons: A Personal View

In modern physics, there is nothing equivalent to the ultimatons described in The Urantia Book. And that necessarily leads me to the following question: Why, despite the limitations the revelators claim, does the book reveal their existence and give us details like the fact that the electron is composed of 100 of these units?

Everything before ultimatons, the primordial force and emergent energies (described in section 2 of document 42), may not be the subject of physical science, but of metaphysics, but ultimatons, “the first measurable form of energy,” seem to fall clearly within the realm of physics, so why are they giving us this information?

Ultimatons react to circular gravity, that of Paradise, but not to linear gravity, that of the mutual attraction of masses. This suggests they have no mass, since the primary manifestation of mass is its mutual attraction, linear gravity.

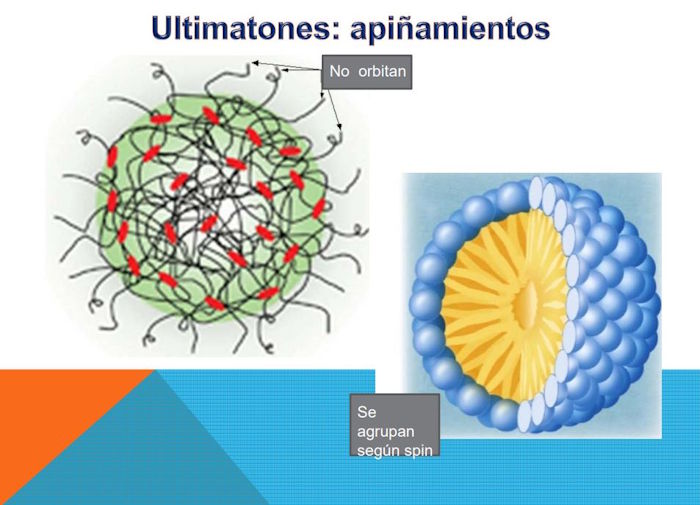

The book tells us that the electron is composed of one hundred ultimatons that “do not describe orbits or whirl about in circuits within the electrons, but they do spread or cluster in accordance with their axial revolutionary velocities.” And a little later, “This same ultimatonic velocity of axial revolution also determines the negative or positive reactions of the several types of electronic units. The entire segregation and grouping of electronic matter, together with the electric differentiation of negative and positive bodies of energy-matter, result from these various functions of the component ultimatonic interassociation” UB 42:6.6.

From these curiously worded phrases, I draw the following conclusions:

- That ultimatons not only have no mass, but also no electric charge, weak charge, or color charge. In fact, one might think of them as “prior” to these characteristics of elementary particles. They are only distinguished by their “axial revolution speeds”; ultimatons have different axial revolution speeds, and that is their only characteristic: spin.

- That all the particles that the book calls electronic matter (not only the electron, but also protons and neutrons, or perhaps quarks) are composed of 100 ultimatons.

- That the hundred ultimatons that form the “electronic” particles are organized into structures formed by blocks of ultimatons with the same axial revolution speed.

- The spin of a particle is the sum of the axial revolution velocities of its component ultimatons (it can be assumed that these velocities have different spin directions and that, consequently, this sum is composed of terms of different signs). This sum determines the type of particle (fermion, boson).

- That the shape of these structures, the number of ultimaton clusters with the same axial revolution speed, and their arrangement (how they “unfold” or “cluster”) within the particle determine its other physical characteristics: mass, electric charge, weak charge, and color charge. In other words, it determines the particle’s response to the four basic interactions (mass, electric charge, weak charge, color charge).

The above quotations speak explicitly of mass (“the segregation and grouping of electronic matter”) and electric charge (“the electrical differentiation into negative and positive matter-energy bodies”), but we can understand that they also speak of weak charge and color charge, although since these were not as well known to humans at the time of the preparation of the revelation, the reference is more obscure (“This same ultimatonic velocity of axial revolution also determines the negative or positive reactions of the several types of electronic units” UB 42:6.6).

¶ 9. The substance of the spirit and the substance of morontia: some personal musings

It is common to think of spirits and the spirit world as something ethereal and diffuse, perhaps outside our world. To some, being spirit means “floating on a cloud playing a fife.” The Urantia Book gives us a very different view. It tells us, for example: “The material universe is always the arena wherein take place all spiritual activities; spirit beings and spirit ascenders live and work on physical spheres of material reality” UB 12:8.1. And “In accordance with well-known laws, we can and do measure spiritual gravity just as man attempts to compute the workings of finite physical gravity” UB 7:1.8. And again, “Spirit realities respond to the attractive power of the spirit center of gravity according to their qualitative value, their degree of spirit nature.” Spirit substance (quality) responds to spirit gravity just as the organized energy of physical matter (quantity) responds to physical gravity. Spiritual values and spirit forces are real UB 7:1.3.

Wow! Well-known laws that measure spiritual gravity, the substance of spirit that reacts to spiritual gravity just as matter reacts to physical gravity. This sounds like spiritual physics, something similar and parallel to the physics of matter.

Just as there is an ultimaton, which is the basis of all matter-energy, is there also a spiriton, which would be the basis of all substance of spirit? In this case, just as the substance of matter, matter-energy, is built from the ultimaton, the substance of spirit would be built from the spiriton. Elementary particles of spirit? Atoms and molecules of spirit? Well-defined laws that regulate their functioning? I’m not saying that matter and spirit are the same, but they are two aspects of the same reality. Matter is measured in quantity, and spirit in quality, but this distinction is characteristic of the universes of space; in Paradise, matter and spirit are indistinguishable. I’m not saying they are the same, but I am saying that perhaps a certain parallel can be established to study both realities. We know, because the book tells us so, that spirit is “the highest personal reality” and that “Spirit is the fundamental reality of the personality experience of all creatures, for God is spirit” UB 12:8.14. We also know that “spirit is the basic personal reality of the universes” and that “materiality can be thought of as a shadow of the more real spirit substance.” So perhaps matter-energy physics is only a shadow of spirit physics.

And the moroncia?

The book tells us that the “warp of morontia is spiritual, its woof physical” UB 0:5.12. The morontia substance could thus be a combination of ultimatons and spiritons in varying degrees. In our transition from matter to spirit, we will have 570 different morontia bodies, and we are told that “as you successively pass through the 570 progressive transformations, you ascend from the material state to the spiritual state of creature life” and that “Eight of these occur in the system, seventy-one in the constellation, and 491 during the sojourn on the Salvington spheres” UB 48:1.5. As we progress, our bodies will have less of a material and more of a spiritual component. In this way, we go from having a material body of flesh and blood, composed only of ultimatons (at the base of the edifice of matter), to a body with many ultimatons and few spiritons (at the base of the edifice of morontia substance) in the first mansion world. Then, as we progress, our body has fewer ultimatons and more spiritons, until we leave the local universe and our body will no longer have ultimatons, only spiritons (at the base of the edifice of spirit substance). We will be spirits.

And that’s where our spiritual life begins… and that’s where my presentation ends. Thank you for your attention.