© 1999 Dick Bain

© 1999 The Brotherhood of Man Library

In Hindu theology, when Brahma breathes out, the universe appears; when he breathes in, the universe disappears. The Urantia Book has a similar concept called space respiration. The authors provide a verbal picture of this phenomenon, but there is much that we are not told. What additional details can we deduce from the information in the book?

¶ What is Space Respiration?

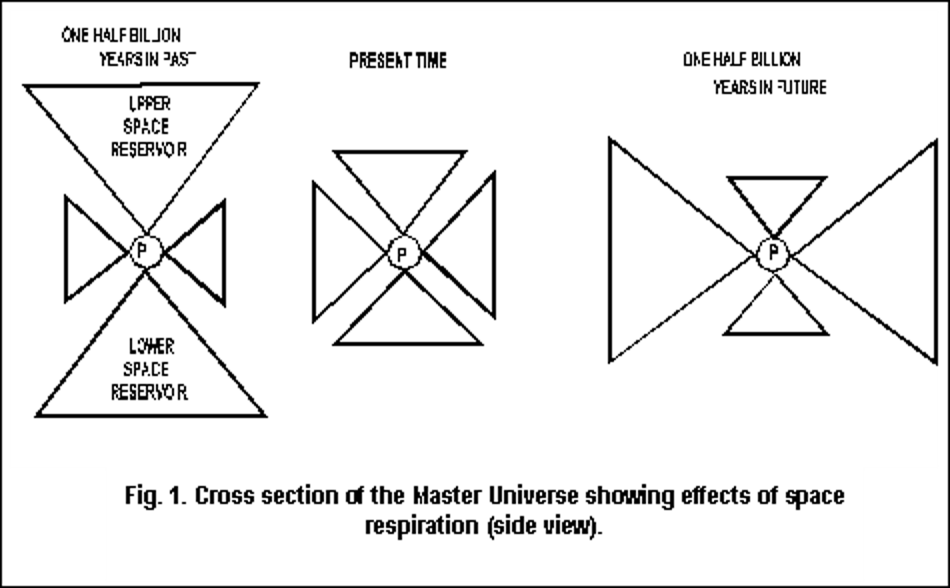

The Urantia Book devotes a section of Paper 11 to space respiration. In this section, we are told that a vertical cross section of the master universe resembles a Maltese cross. The authors inform us that the master universe and space reservoirs engage in a two billion yearlong cycle consisting of an expansion followed by a contraction. We are further told that the master universe is half way through the portion of the cycle in which it expands and the space reservoirs contract. Figure. 1 illustrates a vertical cross section of the Master Universe and the expansion/contraction cycles. The authors also inform us that the material universes participate in the expansion and that it is uniform expansion. (UB 12:4.12)

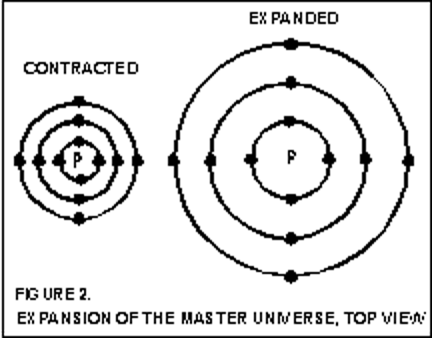

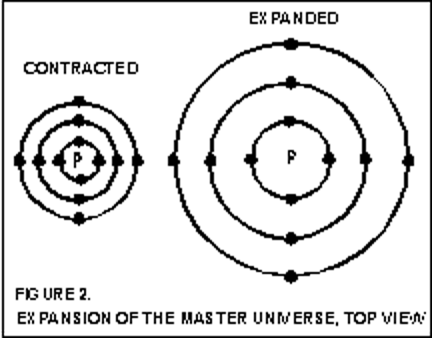

In a uniform expansion, all bodies are moving away from one another at the same rate. An analogy of this used by astronomer George Gamow and others is that of raisins in a raisin muffin. As the muffin cooks, it expands and the raisins all move away from each other. Figure. 2 depicts a horizontal cross section of the Master Universe looking down on upper Paradise depicting the expansion phase of the universe. Small circles representing galaxies are placed on each of the large concentric rings to show how galaxies move away from one another as the universe expands. It is important to note that the further away from the center the galaxies are, the faster they must move to keep the spacing equal between the rings. This in fact is the way that astronomers believe that the universe expands due to the postulated Big Bang.

¶ Information Supplied and not Supplied

The authors give us only a few pieces of numerical information about the universe. One piece informs us that an entire expansion/contraction cycle takes two billion years. (UB 12:4.12) A second point is that we are half way through the expansion phase. Another suggests that the thickness of the first outer space level is about 50 million light years. (UB 12:1.14) A forth implies that the superuniverse level is about 500,000 light years thick. (UB 32:2.11) A light year is the distance that light travels in a year, which is about six trillion miles.

Finally, the authors inform us that the red shift we observe in the light from distant galaxies is not due to them flying away from us. (UB 12:4.15) Note however, that since the universe is supposedly expanding, there will be some red shift caused by this expansion. Several of the things they do not tell us are: How far does the Master Universe expand or contract and what sort of expansion/contraction curve does space respiration follow? There are several other pieces of information that would be useful. What is the average radius of Havona? What is the apparent radius of Paradise in our time space universe? Although Paradise is outside of time and space, the entrance or portal to it must have some size in space. The portal could well be the same physical diameter as Paradise. The authors also do not tell us how much of the red shift we observe in the light from distant galaxies is due to the passage of light through space, and how much is due to the present expansion of the Master Universe.

¶ Space Respiration Expansion Curve

What sort of curve of velocity versus time might space respiration follow? Consider this: Material bodies cannot instantly go from rest to some high speed; they must accelerate to that speed at a reasonable rate. As an example, consider the problems associated with sending a rocket ship to land on a planet circling a distant star. If we start out with the ship motionless in space, we must accelerate gradually to reach a given speed. The speed increases at a rate dependent on the acceleration caused by the force exerted by the rocket motor on the spacecraft.

Acceleration is limited by the fact that we human beings can’t handle many G’s of acceleration over a long period of time. (“G” is the force of gravity at the earth’s surface.) If we accelerated until we got halfway to the distant planet, then we’d have to turn the ship around and decelerate the rest of the way to get down to landing speed. In a similar fashion, the expansion of the universe could not go from 0 to full speed instantly; there needs to be a period of acceleration at the beginning. Likewise, unless God chooses to fiddle with the laws of physics, there needs to be a period of deceleration at the end of both the expansion and contraction phases.

The upper curve of Figure 3 shows how the size of the universe changes throughout the space respiration cycle. Smax and Smin are the maximum and minimum sizes of the master universe. The lower curve of Figure 3 shows how the velocity curve might change during the expansion/contraction cycles. Vmax and Vmin are the maximum and minimum velocities at any given point in the master universe. This shape is known as a sine wave curve. Each phase begins and ends with zero velocity. Maximum velocity is achieved halfway through each phase and acceleration falls to zero at this point. The expansion begins to decelerate and continues until it reaches zero velocity. At this point, the master universe has achieved its maximum expansion and is ready to begin its contraction phase. The contraction phase retraces the acceleration/deceleration path of the expansion phase. The velocity during the contraction phase is negative since it is in the opposite direction compared to the expansion phase. To me, this seems a reasonable scenario for the space respiration expansion and contraction cycles.

¶ Maximum and Minimum Size of the Observable Universe.

I have chosen to limit this discussion to the observable universe because that is all our astronomers are able to measure. The Urantia Book seems to indicate that this observable universe extends only to the outer edge of the first outer space level. (UB 12:1.14) If the first outer space level and the superuniverse level together are about 51 million light years thick, how thick or what is the radius from the center of rotation (Paradise) to the outer edge of the first OSL?

In a previous article, I determined that the radius of the central universe was probably less than 1000 light years [1] If so, then its size is small enough to neglect in calculating the radius and volume of the visible universe.

If the average radius to the outer edge of the first outer space level is about 51 million light years, can we make any predictions as to the amount of contraction and expansion of the universe? (I say average radius because the orbital track of the superuniverses and outer space levels is not a circle, but rather is shaped like a racetrack. Unfortunately, The Urantia Book does not tell us the maximum and minimum radii of the orbital path.) The amount of contraction is perhaps the easiest part to bracket. We know that the universe cannot contract to zero size, and there are practical limits on just how small it can get. But before we consider that, we need to ask if the galaxies and superuniverses themselves contract and expand with the universe.

We can be sure that the distance between galaxies increases as the universe expands, but what about the space between the stars within a galaxy? The Urantia Book says that the material creation participates (UB 12:4.12) in space respiration, but does that mean that the galaxies expand as the universe expands and vice versa? Do the galaxies keep their shape and size throughout the space respiration cycles or do they contract and expand with space during the contraction and expansion phases? Each scenario has its problems.

Physicists tell us that the balance between gravity and the forces created by rotation is what prevents galaxies from flying apart or collapsing. If we assume that galaxies do not change size as the universe expands and contracts, what are the consequences? As the universe expands, the galaxies will move farther and farther apart. This doesn’t seem to pose a problem. However, as the universe contracts, the superuniverses will come closer together. We are not informed on how much space exists between superuniverses but there could be a large buffer zone between them. If the superuniverses keep their present size, as the universe contracts, the galaxies that comprise the superuniverses would eventually come close enough to mutually disrupt each other. This clearly would not be acceptable.

Again, since the authors don’t indicate how much of a buffer zone exists between the superuniverses, we can only make a reasoned judgment about the amount of contraction that is acceptable. 50% sounds to me like a reasonable amount for the maximum contraction. If the universe contracts by 25.5 light years from its present size, then it seems logical to assume that it expands by an equal amount referenced to its present size.

The other possibility is that everything contracts as the universe contracts, and expands as the universe expands. This would mean galaxies, planets, people, and perhaps even molecules and atoms would change size in proportion to the change in the size of the universe. To make this scheme work, either the mass of the basic particles would have to increase or the gravitational constant would have to increase as the universe expanded, and decrease as the universe contracted to maintain the same gravitational force between objects. This would maintain the same gravitational forces between planets, stars, and galaxies, thus preventing disruption due to changes in gravitational force as the bodies come closer together. Is there any way to determine which of the two concepts is correct?

The authors tell us that the superuniverses participate in space expansion. They also tell us that material bodies work against Paradise gravity during the expansion phase and with Paradise gravity during the contraction phase of space respiration. (UB 12:5.1) To me, this suggests that stars, galaxies, and all material bodies resist expansion and contraction. The idea introduced in the previous paragraph that the constants of the universe are not constant seems outrageous. The simplest solution is that the forces between atoms, molecules and larger bodies are much stronger than the expansion of the space within the bodies, and thus the bodies do not expand and contract in size during space respiration. If we accept this as a working hypothesis, can we find evidence of space respiration as we look out into the universe?

Consider that the further a galaxy is from us, the longer it takes for its light to reach us. Because of this, we are looking further back in time as we look further out into the universe.

If the figures given in The Urantia Book are correct, the light we see today from the outer edge of the first outer space level started out about 50 million years ago. What was going on out there 50 million years ago? Since we are now at the highest velocity point on the lower curve of Fig. 3, then the velocity of the edge of the 1st OSL would be less in the past than it is today. This would give the appearance of non-uniform expansion. We should be able to look at the red shift of that region and calculate the velocity, but there is a fly in the ointment. The Urantia Book tells us that much of the red shift we see is due to the passage of light through space, not the velocity away from us. We may be stuck at this point. We don’t know the formula for the amount of red shift due only to the passage of light through space. We could use the assumptions that we have made to calculate the expected red shift due solely to the velocity of the 1st OSL and use that to determine the extra red shift, but this seems like picking ourselves up by our own bootstraps. And further, this whole exercise stands on a chain of assumptions. Change any one of them, and the whole analysis falls apart. What is required is incontrovertible proof that light can be red shifted just by its passage through space.

A small minority of astronomers feel that there is non-velocity red shift, but none of them can offer the sort of proof needed, nor, as far as I know, has any of them come up with a number for this non-velocity red shift. There have been some physicists who claim that the Compton effect could cause the red shift. When radiation such as light interacts with a free charged particle, the energy can be re-radiated at either the same frequency, or at a higher or lower frequency. [2]

I have seen papers on the Internet claiming that most of the red shift in light from distant sources could be due to the Compton effect operating within intervening particles. But there are others who vehemently deny the possibility. Therefore, until reliable proof and numbers are forthcoming, the best we can do is speculate.

All the foregoing discussion was based on accepting the figures in The Urantia Book for the size of things. If those figures are in error, then all the preceding speculation is moot. Our astronomers believe that the universe is about 12 billion years old based on red shift measurements; we can infer from information in The Urantia Book that the universe is trillions of years old. (UB 57:1.3) Our astronomers believe that the edge of the observable universe is more than 10 billion light years distant, again based mostly on red shift measurements; we can infer from information in The Urantia Book that it is about 50 million light years in radius. If the red shift assumption of our astronomers is incorrect, then the universe size and age they have determined are seriously in error.

At present, I don’t see any way to reconcile the findings of the astronomers with the information in The Urantia Book, or to determine which is correct. It may turn out in the end that both are partly in error. I would be very pleased to find out that The Urantia Book has it exactly right, but unfortunately the authors put in an accuracy disclaimer regarding the science and cosmology of the book. It seems that I will have to wait until the evidence is in before I can decide on the correctness of any science or astronomy information in the book.

Speculation won’t necessarily provide correct answers, but it can help us to frame the questions. It often turns out that asking the right questions is half the battle in finding the right answers. I hope no one is ever so overawed with the spiritual parts of The Urantia Book that they are afraid to question the science of the book. As far as I am concerned, the science disclaimer (UB 101:4.2) gives us license to question the science and cosmology of The Urantia Book. So speculate on!