© 2008 Halbert Katzen, JD

Prepared by Halbert Katzen, J.D. with assistance fromChris Halvorson, Ph.D. [Updated 07/11/2009]

¶ Sierra Mountains Summary

A longstanding controversy has existed over when the Sierra Mountains were formed. Two schools of thought developed, referred to as the Old Sierras and the New Sierras theories. The Old Sierras theory holds that the Sierra Mountains formed about 50 million years ago; the New Sierras theory asserts that they are only about 5 million years old. Though the controversy is not entirely laid to rest by research published in 2006, this new approach to dating the mountains employs a technology that is much more specific than previous methodologies and has been widely accepted as reliable when used in other applications. The results are harmonious with the Old Sierras theory and what was asserted by The Urantia Book in 1955.

¶ Sierra Mountains Overview

There is a long-standing controversy surrounding the age of the Sierra mountain range. The New Sierra theory, first presented in the 1880 os, states that the Sierra Mountains are about five million years old. In contrast, the Old Sierra theory, published in 1911, posits that the Sierra mountain range is 40 to 50 million years old. Academics argued over the merits of these two theories throughout the twentieth century, without reaching a consensus, but the New Sierra theory became more popular and was widely taught in grade schools.

Going against popular opinion at the time, The Urantia Book, published in 1955, asserts that about forty million years ago the land areas in North America was elevated, which is consistent with the Old Sierra theory. In addition, The Urantia Book states that the Sierra mountain range has been rising for about the last twenty five million years.

Recently, new evidence has come to light that supports the position taken by The Urantia Book and the Old Sierra theory. In 2006 a trio of Stanford scientists published research dating the formation of the Sierra Nevada range to fifty million years ago. These Stanford scientists, Andreas Mulch, Stephan A. Graham, and C. Page Chamberlain, used an innovative technique involving the study of precipitation that was trapped in ancient clay beds.

None of this would have been possible without a bit of historical serendipity. In order to study these ancient raindrops, the Stanford team needed deposits of the mineral kaolinite. This mineral forms in some soils when rainwater is combined with clay, and it keeps the chemical composition of the rainwater intact. Normally these kaolinite deposits would have been buried deep within the mountains, covered by millions of years of sedimentary build-up, but in the Sierras kaolinite lays uncovered in many abandoned nineteenth century gold-mining camps. Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain were able to date the kaolinite to forty to fifty millions years ago, then all they had to do was compare to chemical compositions of the various kaolinite samples to determine the height of the Sierra Nevada range at that point in time.

Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain realized they could use the basic chemistry of rainwater to determine the age and height of the Sierra Mountains because one of the elements in raindrops, hydrogen, exists in two different forms, or “isotopes”. The normal hydrogen isotope contains one proton and no neutrons in its nucleus, while deuterium, the other hydrogen isotope, adds a neutron to the nucleus. Scientists had previously used variations in these isotopes to track hurricanes and bird migrations, so this Stanford trio figured they could apply it to mountains, too.

As a raincloud passes over a mountain, it releases raindrops comprised of heavier isotopes at lower elevations, then releases the lighter raindrops as it reaches higher elevations. Therefore, by comparing the chemical composition of ancient raindrops at various locations to current precipitation at those same locations, it was possible for these scientists to determine the relative height of different sections of land. The comparison was essentially identical.

Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain found that the mountain range elevated about fifty million years ago, just as The Urantia Book describes. Furthermore, they found that a minor uplift in the Sierras occurred between three and five million years ago, possibly leaving false clues that the range is only a few million years old.

Despite the sound scientific basis of this research, it has not entirely put an end to the Old Sierra vs. New Sierra argument. Since this isotope comparison technique has never before been used to determine the age and height of mountains, some New Sierra believers contend that there is some flaw in the method that we do not yet understand. However, the method’s relative simplicity and its reliability when used in other fields make it very hard to attack. Indeed, no scientist has yet been able to find a specific flaw in the research.

Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain seem to have at last determined scientifically what The Urantia Book asserted back in 1955-the Sierra Nevada mountain range is at least 40 to 50 million years old.

¶ Sierra Mountains Review

A longstanding controversy has existed over when the Sierra Mountains were formed. Two schools of thought developed, referred to as the Old Sierras and the New Sierras theories. The Old Sierras theory holds that the Sierra Mountains formed about 40 to 50 million years ago; the New Sierras theory asserts that they are only about 5 million years old. Though the controversy is not entirely laid to rest by research published in 2006, this new approach to dating the mountains employs a technology that is much more specific than previous methodologies and has been widely accepted as reliable when used in other applications. The results are harmonious with what was asserted by The Urantia Book in 1955.

The Urantia Book states:

40,000,000 years ago the land areas of the Northern Hemisphere began to elevate, and this was followed by new extensive land deposits and other terrestrial activities, including lava flows, warping, lake formation, and erosion. UB 61:1.11 [1]

25,000,000 years ago there was a slight land submergence following the long epoch of land elevation. The Rocky Mountain region remained highly elevated so that the deposition of erosion material continued throughout the lowlands to the east. The Sierras were well re-elevated; in fact, they have been rising ever since. UB 61:3.3 [2]

The Urantia Book’s assertion that these mountains originated 40 million years ago and have been rising for the last 25 million years conflicts with the New Sierras theory. Obviously, if they have been rising for the last 25 million years, then the theory that they have been rising for the last five million years is not completely off base; the evidence that supports that they have been rising for the last five million years has a limited degree of consistency with what The Urantia Book says about them “rising ever since” 25 million years ago. In fact, even this new research technique indicates the mountains were rising slightly five million years ago. But the theory that these mountains were fundamentally formed about five million years ago is fundamentally in conflict with The Urantia Book. The Urantia Book asserts, and the new study published in 2006 supports, the view that this mountain range was in existence, and has maintained its stature since, much earlier than five million years ago.

Science Magazine published a report on this new research on July 7, 2006. The report, Hydrogen Isotopes in Eocene River Gravels and Paleoelevation of the Sierra Nevada, written by Andreas Mulch, Stephan A. Graham, and C. Page Chamberlain, summarizes the findings this way:

We determine paleoelevation [ancient elevation] of the Sierra Nevada, California, by tracking the effect of topography on precipitation, as recorded in hydrogen isotopes of kaolinite exposed in gold-bearing river deposits from the Eocene Yuba River. The data, compared with the modern isotopic composition of precipitation, show that about 40 to 50 million years ago the Sierra Nevada stood tall (2200 meters), a result in conflict with proposed young surface uplift by tectonic and climatic forcing but consistent with the Sierra Nevada representing the edge of a pre-Eocene [before approximately 55 million years ago] continental plateau. [3]

(The word “Urantia,” denoting Earth, is a coined word in The Urantia Book, with the etymological meaning “(y)our place in the heavens.” The Urantia Book gives an extensive history of both the geophysical evolution of the planet and the evolutionary development of life. In general, the dates given in The Urantia Book regarding the evolutionary developments of the last 35 million years correspond with the dates yielded by radiometric dating. Between 35 million and 450 million years ago, radiometric dates are inflated by an average factor of 1.5 , with the factor slightly increasing from the later to the more recent dates, followed by a more rapid decrease to 1.o. Backward from 450 to 550 million years ago, the factor increases from 1.4 to 4.0. Backward from 550 million years ago radiometric dates are consistently inflated by a factor of 4.0 in comparison to the dates in The Urantia Book. The Urantia Book says that 550 million years ago is when eukaryotic (evolutionary) life was implanted on the planet, that 450 million years ago marks the appearance of protozoa, and that 35 million years ago is the beginning of the age of advanced mammals. Physicist Chris Halvorson, Ph.D., thinks-based on, for example, the implications of the discovery of massive quantities of “unstable” technetium and promethium in the atmospheres of some stars-that the rate of radioactive decay can be altered by the environment, specifically, that the spatial environment has been regulated as part of the divine overcontrol of the evolution of life on this planet. Taken in this light, the theory that the Sierras developed around 50 million years ago is consistent with the assertion in The Urantia Book that they developed around 40 million years ago.)

Typically, UBtheNEWS reports quote the original research on which they are based as extensively as possible. This is done so that readers of these reports do not have to trust the author(s) interpretation of the scientific reports that corroborate information in The Urantia Book. In this case, the research is especially technical and would require thousands of words to explain and define the terminology used in the original report. Fortunately, Brittany Grayson, an intern for Discover Magazine, wrote an article called The Sierra Nevada Enigma. This article not only covers the conclusions and implications of the research done by Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain, but also provides a history of the controversy surrounding this subject and how this new research has been received. Therefore, with much thanks to Ms. Grayson, her article will be extensively quoted as an efficient means of providing the substance of the Sierra Nevada Report from an independent source. Extraneous material is edited out for the sake of brevity.

From The Sierra Nevada Enigma:

The mountains of the High Sierra, the backbone of California, rise out [of] the mist to tower over the red plain and rocky valleys below. . . They are a riddle. After more than a century of speculation and study, no one knows how old they are.

For years, teachers have used the history of the Sierra Nevada as a classic lesson in plate tectonics. The mountains began to rise about 4 million years ago, the lesson goes. This is the prevailing wisdom, bequeathed to Californians from turn-of-thecentury geologists. More recently, scientists studying the impressions carved into tilted bedrock by ancient rivers disagreed. The Sierra began ascending 20 million to 25 million years ago, they concluded.

The answer to this puzzle may lie in the awful scars left on the mountains by the goldhungry miners known as the 49ers. Three geologic detectives from Stanford University have followed a trail of ancient raindrops to arrive at a new, much older, estimate of the Sierra Nevada’s age. The researchers scoured now-defunct mining camps for clay samples that encoded the chemical signature of rain from long ago. These faint traces revealed how the altitudes of the ancient mountains changed over the millennia. The technique-tried-and-true in other settings, but never used for mountain building-says the Sierra are at least 45 million years old, nearly twice the canonical estimate.

“The major success of this study,” says Andreas Mulch, lead author on the team’s paper in Science, “is that it is actually a really, really simple problem we were trying to attack: How high is high?” [4]

The Urantia Book not only says that the Sierras were “well re-elevated” and have been rising for the last 25 million years, rejecting the theory that they are only about 5 million years old, but also contains statements that are harmonious with the findings by Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain that the Sierras were elevated 45 million years ago.

Referring to the period prior to and then ending about 50 to 60 million years ago, The Urantia Book states, “The youngest mountains are in the Rocky Mountain system, where, for ages, land elevations had occurred only to be successively covered by the sea, though some of the higher lands remained as islands. … [A] real mountain highland was elevated which was destined, subsequently, to be carved into the present Rocky Mountains by the combined artistry of nature’s elements.” [5]

In the next chapter it says, “45,000,000 years ago the continental backbones were elevated in association with a very general sinking of the coast lines.”[6]

Now going back to The Sierra Nevada Enigma:

Roots of the mountain debate

The debate began in the wake of the Gold Rush in the mid-18oos, which bared the mountains’ ancient rock to future geologists. Rivers cut like knives through the mountains millions of years ago, revealing veins of gold. Once eroded from the bedrock veins, the gold intermingled with the gravel of ancient riverbeds. As rapacious miners shattered primordial rocks in search of gold, they traced the paths of those rivers and unearthed them for the first time in millennia.

. . .

In the 188 os Joseph Le Conte roamed the Sierra with his friend John Muir. Le Conte studied the ancient riverbeds. Based upon the way the riverbeds seemed to tilt, Le Conte declared that the mountains must have risen significantly-1,500 to 2,000 meters-in the last few million years.

This school of thought, now called the “Young Sierra” theory, still has adamant followers. They contend the mountains rose 3 million to 5 million years ago-quite recently, in geologic terms. They say the rising, or “uplift,” occurred when an enormous chunk of dense rock broke off the bottom of one plate and sank into Earth’s hot mantle. This lightened the plate above, allowing it to buoy up like a balloon cut free of its leaden anchor.

The first dissension arose in 1911 when geologist Waldemar Lindgren, working with the United States Geological Survey, published a map of what the ancient routes of the rivers might have been.

Stephan Graham, the expert in ancient riverbeds on the Stanford team, says Lindgren’s paper began this brush fire of a debate. "Lindgren generated a bunch of maps that reconstructed the Sierra landscape. He showed there were drainage systems in the Sierra 40 or 50 million years ago that didn’t look so much different

Geologists who support Lindgren claim the mountains rose long ago and escaped most of the effects of erosion. They assert the modern mountains formed in a collision of mammoth proportions when part of the Pacific Plate crashed into and slid under the North American plate. The rock of the top plate had nowhere to go but up. The mountains probably rose to their modern height at least 25 million years ago, these geologists believe.

Since Lindgren’s time, geologists and paleontologists have tackled this problem with every tool in their scientific kits. Some plumb the depths of gorges or study the remaining gravel, and some try to establish the age of volcanic rocks from ancient eruptions. Others use chemistry to track radioactive decay of minerals. None of these studies yielded a conclusive result; many only widened the rift between the Young Sierra and Old Sierra camps.

Silver lining of a disaster

The solution may lie in places like Malakoff Diggins State Historical Park. . . . Malakoff Diggins is the open wound left by only a few decades of prospectors’ insistent hands.

. . . When gold got too scarce for miners to pan for it by hand, they brought in enormous water cannons to make the job more efficient. . . . Called “monitors” or simply “giants,” the cannons shot streams of water at the sides of the mountain to shear soil and sediment away from the mountain slopes…

… Malakoff Diggins was the largest hydraulic mine of its time. …

… [P]reserved is the gaping gash the miners left: 2100 meters long, 900 meters wide, and nearly 200 meters deep in places.

. . .

This scene proved central to the investigations by the triumvirate of Stanford scientists-Andreas Mulch, Stephan Graham, and Page Chamberlain. Mulch was a postdoctoral researcher at the time, a geologist in love with labwork and fieldwork and eager to do both at once. He worked under Chamberlain, a geochemist who used subtle chemical fingerprints to study his two disparate passions: birds and rocks. Before tracking the growth of mountains, Chamberlain used chemical clues to trace bird migrations. .

Of the three geologists, Graham has pondered the age of the Sierra the longest…

. . .“I was aware of the issues, but there weren’t new methods to be applied.” That changed when he met Chamberlain, who offered him an unexpected tool: isotope ratios.

Chamberlain studies the ratios of elements and their isotopes, and how and why those ratios shift. An isotope is an atom of an element that has either acquired or lost a neutron in its nucleus. This does not affect the atom’s charge, but it does change its weight. Specifically, Chamberlain is interested in the isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen that exist naturally in rainwater.

Rainwater has two forms of hydrogen: the normal form, with one proton and no neutrons, and rarer deuterium, which adds a neutron. Scientists have used variations in these isotopes to track hurricanes and follow bird migrations. Chamberlain figured he could chart the growth of mountains as well [ ] by tracing water deep into the past.

When rain clouds cross mountains, they scrape up the side and drag their bellies over the peaks. As a rain cloud ascends, it releases raindrops containing water with heavy isotopes first, then lighter isotopes at higher elevations, like a mountain climber lightening her pack for the hard climb ahead. The thirsty earth of the mountain soil catches the raindrops. In some soils, adding water transforms the clay into another mineral: kaolinite. That mineral incorporates the molecular signature of the rainwater.

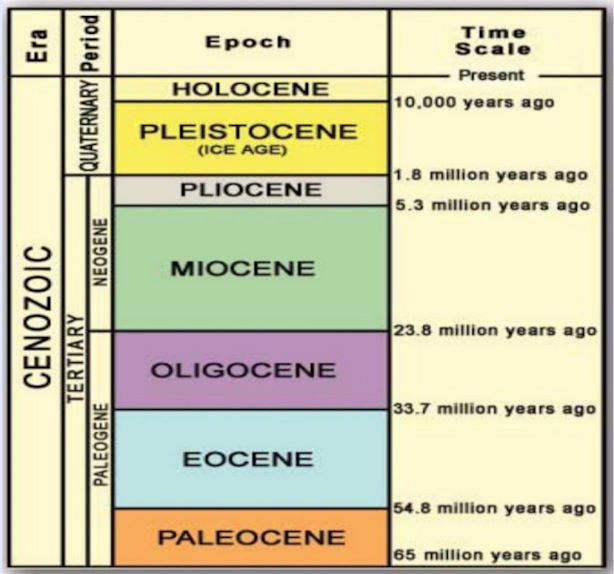

The kaolinite the geologists studied came from river deposits that date back to the Eocene era, some 40 million to 50 million years ago. Scientists know how old these rocks are, but they can’t be sure of their ancient altitude. The kaolinite could have formed just as easily at sea level or on top of a mountain. Only unlocking the chemical signature of its formative raindrop can reveal that secret.

Millennia ago, layers of new soil covered the raindrop-bearing kaolinite. Luckily for the geologists, the kaolinite persists in the primeval riverbed formations. These same deposits held the gold that drew miners west. The miners laid bare both gold and kaolinite again when they assaulted the Sierra with hydraulic cannons in the late 19th century. To collect kaolinite samples, the geologists simply had to go to abandoned mining camps and pick it up.

Mulch, who led the Stanford study, says the research was only possible because of the covetousness of the 49ers. “People were looking for the gold, so everyone was trying to find these particular river deposits in order to become rich and famous,” Mulch says. "Without the miners who actually produced these huge environmental changes by ripping up these entire mountain ranges, we would never have had the rock that we used.

Decoding the drops

The Sierra are perfect for using raindrops to trace the face of a mountain," Graham says. Researchers know precisely where the ancient sea used to lap up against the mountains, farther inland than it is today. That’s not the case with mountain ranges in more complex regions, like the Himalaya.

The beauty of this particular place is that you know where the beach was at any particular time,“ Graham says. ”You can walk from the beach, where the rivers entered the sea, through a bay like San Francisco that used to occupy central California, and you can walk upstream to the peaks…

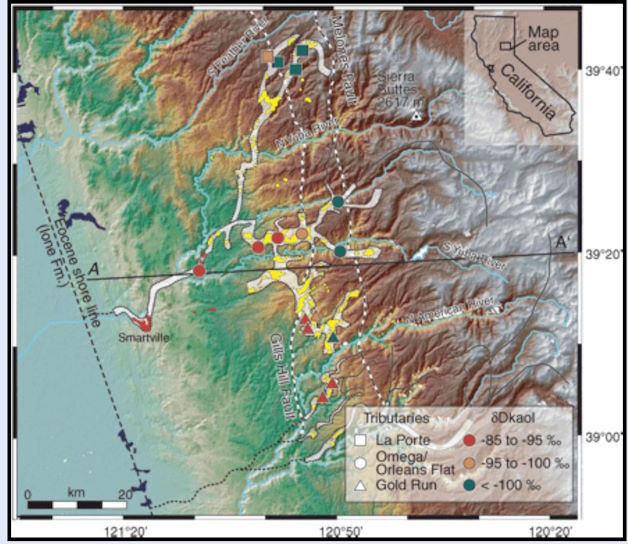

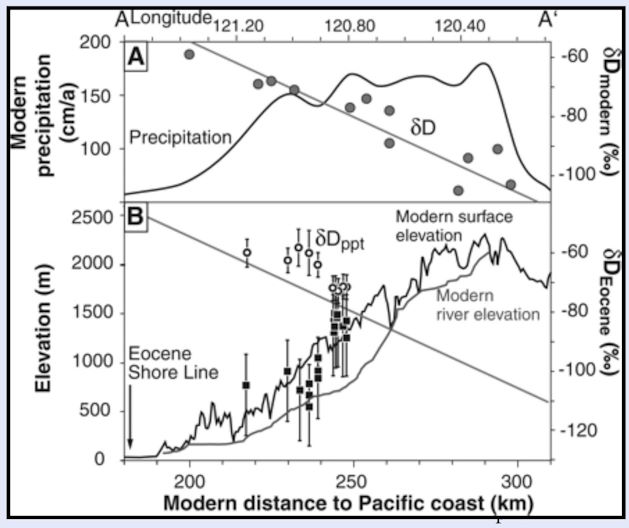

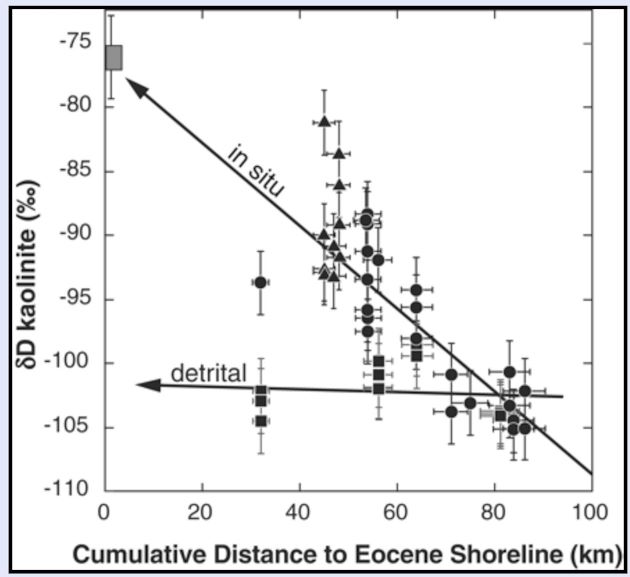

Figures 1 and 3 below, along with the commentary, were included as part of the original research report. [7]

Now going back to The Sierra Nevada Enigma:

All three scientists headed into the Sierra for camping trips, winding up narrow weather-beaten roads. They stayed four or five days at a time, collecting kaolinite from the still-raw patches on the flanks of the mountain. Back at Stanford, Mulch

Mulch heated the kaolinite samples to more than 1450°C, a temperature at which cast iron can be poured like gravy. Intense heat breaks hydrogen’s bond to oxygen, baking hydrogen gas out of the sample. Then Mulch analyzed its chemical signature in a mass spectrometer. This sensitive device analyzes how much of the sample is normal hydrogen and how much is the heavier isotope, deuterium.

The team took 34 samples of ancient kaolinite and determined how much deuterium each contained. Because the scientists knew where the ancient sea level was, they could determine how much deuterium was in the raindrops that fell there. Those that fell on the seashore contained the most deuterium, because the heaviest raindrops fall on the lowest places. As the clouds traveled farther up the mountains, each raindrop contained less deuterium, on average. Using the amount of deuterium in the coastline raindrops as a baseline, they were able to project how far up the mountain each kaolinite-encased raindrop fell. Using an equation to quantify this relationship, they could pinpoint the ancient altitude of each kaolinite sample.

Comparing the composition of these ancient kaolinite samples to modern ones showed something surprising: Within margins of error, they were identical. That meant the elevation of the Sierra has not changed significantly in the last 45 million years. Because the mountains were at their current height that long ago, they must have formed even earlier, though this study cannot tell when that was.

Figure 2 below, along with the commentary, was included as part of the original research report.research report. [8]

Now going back again to The Sierra Nevada Enigma:

Results and rebuttal

Some of the first reactions were squawks of indignation. The ages couldn’t be right, the Young Sierra camp said, because erosion would have worn away the mountains by now. According to Mulch, they have maintained their height because the active tectonic plates lift the mountains at about the same rate that wind, weather, and water shears layers off their peaks.

Mulch says his study even may explain some of the data supporting the Young Sierra theory. The team discovered evidence for a slight uplift-about 300 to 600 meters-of the mountains 3 million to 5 million years ago. This smaller upheaval may have left red herrings for geologists to find and interpret as evidence of significant recent mountain growth.

Chamberlain says the simplicity of the study makes it almost unassailable, even though it clashes with the dogma of the Sierra as young. “The data show no evidence for a recent uplift,” he says. "You’re left with saying isotopes don’t work [if you disagree] [previous bracketed insert is in the original article]. That’s your only option at this point. And if that’s the case, we all need to get out of this business.

Geologist Craig Jones of the University of Colorado in Boulder does disagree. “My gut feeling is that there’s something about the isotopic work we don’t understand yet,” Jones says. "Obviously there’s a tendency to throw out the idea that the newest results are the correct ones.

Jones cannot find anything wrong with the Stanford results, except they contradict other geological evidence he feels supports a younger mountain range. Rainfall chemistry, or its signatures at different elevations, might have been dramatically different in an ancient climate, Jones says; he is sure some error lurks in the method. "It’s very new. It has a lot of promise. It just seems right now that it’s butting heads with a lot of other observations. A lot of times that’s how you kind of work out the kinks.[9]

Brittany Grayson reasonably sought out and found commentary from someone aligned with the “Young Sierras” camp to criticize the work. This criticism, by its own admission is based on “gut feeling” and speculation, not science. The bias of Craig Jones is also reflected by his comment regarding the “tendency to throw out the idea that the newest results are the correct ones.” Indeed, this is precisely how science moves forward. Even Grayson felt the need to comment that, “Jones cannot find anything wrong with the Stanford results, except they contradict other geological evidence he feels supports a younger mountain range.”mountain range."

Jones’, however, does bring up a reasonable scientific argument by pointing out that this research is “butting heads with a lot of other observations.” This goes to the heart of the issue, that there is a history of controversy on this subject because of observations and studies that lead to conflicting conclusions.

Revisiting Grayson’s recounting of the history of the Young Sierras position helps one appreciate the development of the controversy. “In the 1880s Joseph Le Conte roamed the Sierra with his friend John Muir. Le Conte studied the ancient riverbeds. Based upon the way the riverbeds seemed to tilt, Le Conte declared that the mountains must have risen significantly-1,500 to 2,000 meters-in the last few million years.” The momentum for the Young Sierra position originated over 125 years ago, based upon topographic observations. This is not the most precise and enduring technique for reaching scientific conclusions regarding how many millions of years ago mountain ranges were formed.

Once scientific minds take a position, both ego and financial considerations come into play. Is greater evidence being required to refute a theory than what was needed to establish it in the first place? Unbiased analysis demands that no preference be given to which theory came first; if we are to give credence to the idea that science is progressing, then newer, more advanced and less subjective techniques of analysis must be given more credibility than the more dated and subjective approaches of the past.

Approached from this perspective, the 2006 report prepared by Mulch, Graham, and Chamberlain not only bolsters the Old Sierras position, but also lends credibility to the geological history provided in The Urantia Book back in 1955.

¶ External links

- This report in UBTheNews webpage

- Other reports in UBTheNews webpage

- Topical Studies in UBTheNews webpage

¶ Sierra Mountains Additional Links

40,000,000 years ago the land areas of the Northern Hemisphere began to elevate, and this was followed by new extensive land deposits and other terrestrial activities, including lava flows, warping, lake formation, and erosion. UB 61:1.11

25,000,000 years ago there was a slight land submergence following the long epoch of land elevation. The Rocky Mountain region remained highly elevated so that the deposition of erosion material continued throughout the lowlands to the east. The Sierras were well re-elevated; in fact, they have been rising ever since. UB 61:3.3

- http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/313/5783/87 primary research article Science 7 July 2006: Vol. 313. no. 5783, pp. 87 - 89 DOI: 10.1126/science.1125986

- http://scicom.ucsc.edu/SciNotes/0701/sierra/index.html The Sierra Nevada Enigma, heavily quoted article for Sierra Report

- http://www.answers.com/topic/sierra-nevada-us?cat=travel asserting they have been rising for 25 m years

- http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/07/060709125422.htm referencing recent research and mentioning controversy

- http://www.livescience.com/strangenews/060706_sierra_nevada.html repeating the story of the new research

- http://www.stanford.edu/dept/news/pr/2006/pr-sierra-071206.html has contact info researchers and editors

Phil Calabrese article:

Age of Sierra Mountain Range. As another example of The Urantia Book’s uncanny ability to avoid error and provide truth, geologists at Stanford University were able to determine a minimum age for the Sierra Nevada mountain range by examining rain that fell there 45 million years ago that was captured in soaked gravel. They found that it fell at similar altitudes as rain falling there now. (Rain falling at lower altitudes contains a higher percentage of deuterium (heavy hydrogen) than rain falling at high altitudes.) According to Discover Magazine’s Kathy A Svitil, this “settled a long-running dispute over the age of the Sierra Nevada range” in which “most scientists had put the Sierra’s age at under 5 million years old.” [10]

By contrast, the 1955 Urantia Book [11] fully explains, and in great detail, the whole mountain formation process (still largely unrecognized) including how the Sierra’s were initially formed at the end of the Crustaceous period (144 to 65 million years ago, [12]) during the western continental crunch up against an obstruction on the floor of the pacific ocean which ended the westward drift of the North and South American continents. The Sierra’s were subsequently worn down and submerged but then re-elevated by on-going volcanic action. The story is complicated.

“25,000,000 years ago there was a slight land submergence following the long epoch of land elevation. . The Sierras were well re-elevated; in fact, they have been rising ever since.” [13]

Had the authors of the 1955 Urantia Book known no more than most geologists living in 2006, they would likely have given an erroneous account of how the Sierra Nevada’s were formed less than 5 million years ago.

Comment regarding Phil’s article: He states: “the Sierra’s [sic] were initially formed at the end of the Crustaceous [sic] period (144 to 65 million years ago)”. According to The Urantia Book, the Cretaceous period is from 100 to 50 million years ago, and the Sierras began to form near the start of this geologic period. Phil’s dates reflect radiometric dating.

¶ Footnotes

UB 61:1.6 This mode of citation to The Urantia Book provides the chapter (referred to as “Papers” in The Urantia Book), then the section, followed by the paragraph number. ↩︎

Science 7 July 2006: Vol. 313. no. 5783, pp. 87 - 89, http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/313/5783/87 ↩︎

Science 7 July 2006: Vol. 313. no. 5783, pp. 87 - 89, http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/313/5783/87 ↩︎