© 2014 Jacques Rogge

© 2014 French-speaking Association of Readers of the Urantia Book

¶ Some quotes from Baron de Coubertin:

“The important thing in life is not the triumph, but the fight. The essential thing is not to have won, but to have fought well.”

“Success is not a goal but a means to aim higher.”

“See far, speak frankly, act firmly.”

“Sport seeks out fear in order to dominate it, fatigue in order to triumph over it, difficulty in order to overcome it.”

“Each difficulty encountered must be an opportunity for new progress.”

“The important thing is to participate.”

“Stronger, higher, faster.”

¶ Tribute from J. Rogge, former president of the IOC, 1-01-2013

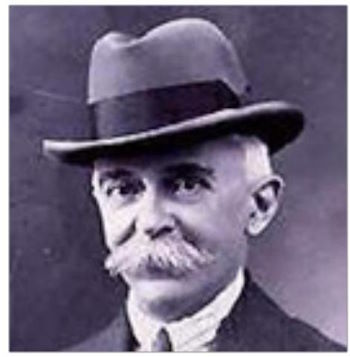

Like many of you, I consider New Year’s Day to be an ideal time to reflect on the past and look to the future. This is especially true today, as January 1, 2013, marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of the founder of the modern Olympic Games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin.

His personal motto was: “See big, speak big, act tough,” but even he could not have predicted how his vision for the Games would transform it into one of the most important cultural events in our history, touching billions of people around the world and entering almost every home on the planet.

Certainly, Pierre de Coubertin would have been delighted to know that 118 years after the creation of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the Olympic Movement is stronger than ever… Important steps have also been taken, particularly with regard to the participation of women in sport, heritage and the environment.

Initiatives to disseminate Olympic values have multiplied, particularly those launched in cooperation with the United Nations to put sport at the service of development. We have also redoubled and intensified our efforts to protect the integrity of sport… It would be easy to forget the herculean task that Pierre de Coubertin had to undertake to re-establish, almost single-handedly, the Olympic Games at the end of the 19th century. He always maintained that organized sport strengthened not only the body, but also the will and the mind, while encouraging universality and fair play, ideas that are widely accepted today…

Despite all these obstacles, he continued to work with determination, offering his time and fortune to breathe new life into the ancient Olympic Games. Not for personal gain but for the good of humanity, because he was convinced that sport conveyed values such as excellence, friendship and respect. With his remarkable intelligence, his absolute certainty and his great strength of character, he gradually won the support and trust of groups of like-minded individuals. In a surprisingly short time, these would become the founding members of the IOC in 1894…

Pierre de Coubertin was the second President of the IOC and his twenty-nine-year term (1896-1925) was the longest in Olympic history. He devoted much of the rest of his life to ensuring the Games and the purity of competition. The Olympic Movement has had its share of challenges, but thanks to Coubertin, it has survived, leaving a legacy that continues to benefit billions of people. In addition to the Olympic Games, he gave us the Olympic rings—one of the most recognizable symbols in the world—the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, the Athletes’ Oath, the Olympic Museum, and the Olympic Charter he wrote… It is indeed the text that sets us apart from all other sports organizations. The IOC does not exist simply to stage a major sporting event every two years. Our mission is to put sport at the service of humanity, with competition helping us to draw out the best in our society and combat its pernicious elements. The Olympic values are still today the common thread that guides everything we do.

Would Pierre de Coubertin be happy with the developments that have taken place since his death in 1937? The answer is obviously no. We have had our share of turbulence, but it is because we have been able to count on the moral and ethical guide that is the Olympic Charter that we have managed to get through them. But he would be delighted that his fundamental values endure. They are even more relevant today. Everything we admired about Olympism in 2012 would not have been possible without his work. It is now up to us to ensure that the Games retain their relevance and integrity for another 118 years and beyond.

Pierre de Coubertin devoted himself body and soul to this cause. On this eve of January 1, the Olympic Movement salutes the man who started it all.

Happy 150th birthday!

Jacques Rogge

¶ Biography of Pierre de Coubertin

Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937) was born on January 1, 1863, in the Le Havre region, to a father who was a genre painter. Schooled by the Jesuits at the rue de Madrid day school in Paris and eligible for Saint-Cyr, he was destined for a military career, but, due to a national political and military decline, it was education that he chose.

Enrolled at the École libre des Sciences Politiques, he spent a long period of study in England, from which he returned admiring the work of Thomas Arnold. The latter, a member of the clergy, director of Rugby College and creator of the British Renewal cell, had placed sport at the heart of the English education system. Coubertin then traveled to the Anglo-Saxon world and concluded that the latter had a recent and non-hereditary power made possible by the sports reform of the education system…

Eager to popularize the sport, he quickly realized that to achieve his goals, it had to be internationalized. This led him to want to restore Olympism, an idea that was certainly not new but carried out in a spirit of modernity that ensured its success. On June 23, 1894, while he brought together two thousand people including seventy-nine representatives from twelve countries at a Congress on athletics in the large amphitheater of the Sorbonne, Coubertin managed to have the project to restore the Olympic Games adopted and create the ad hoc Commission responsible for studying the project, the embryo of the International Olympic Committee.

This is how the year 1896 saw the celebration of the first Olympiad in Athens. Second president of the Olympic institution in anticipation of the Paris Olympic Games in 1900, Pierre de Coubertin retained this position until 1925. He worked tirelessly for the development of the modern Olympic Games, certainly inscribed in his own contemporaneity, but for which he established a protocol regulating the course and symbolism of the Games in the spirit of a Hellenic culture that animated him. He settled in Lausanne in 1915 where he anchored the International Olympic Committee. He died there on September 2, 1937.

As part of the artistic competitions of the 1912 Games, which took place under his own aegis, the jury gave first prize to his Ode to Sport. This medal rewarded his talent as a writer and his literary work, representing around thirty published volumes, or approximately 15,000 printed pages.

¶ Define Olympism

The notion of Olympism is a modern conceptualization discovered by Pierre de Coubertin and developed after him, in particular in support of the cultural heritage of ancient Greece. The term Olympism designates the institutionalized ideal of the Olympic Movement and is often the subject of erroneous use.

It is in fact frequently used to designate, as desired, all the actors of the Olympic Movement, the meaning of their actions, an educational concept, the sectoral organization system of sport, when it is not simply the object of a nihilistic critique. The word is also found too often in the evocation of the ancient Games of Olympia. However, Olympism as such did not exist: the event held on the banks of the Altis was not the autonomous expression of a philosophical movement, but that, unified, of Hellenic cultures. This notion of Olympism is in reality a modern conceptualization discovered by Pierre de Coubertin and developed after him, in particular with the support of the cultural heritage of ancient Greece.

Since it is necessary to refer to the fundamental law of the Movement, let us note immediately that the Olympic Charter defines Olympism as “a philosophy of life, exalting and combining in a balanced whole the qualities of the body, the will and the mind. Combining sport with culture and education, Olympism aims to create a lifestyle based on joy in effort, the educational value of good example and respect for fundamental universal ethical principles” (Fundamental Principle No. 2) with the aim of “putting sport everywhere at the service of the harmonious development of man, with a view to encouraging the establishment of a peaceful society, concerned with preserving human dignity.” (Fundamental Principle No. 3). The two tenants of official Olympism are therefore established: sport, and a systemic vocation to structure the individual for a humanist society.

From this definition, we also note the reference to a philosophy which therefore designates Olympism as a movement of thought put into action, and which is addressed as much to the individual as to the community.

The Olympism disseminated by the ClO is therefore a philosophy of ancient inspiration and universal aspiration intended to convey societal values and messages, in support of an activity, sport, and an event, the Olympic Games, which have become a landmark on the international agenda and the showcase of sporting practice, with, among other things, its structuring qualities and its sociological characteristics.

¶ The rings

The Olympic symbol consists of five intertwined rings of equal dimensions, used alone, in one or five colors which are, from left to right, blue, yellow, black, green and red. The Olympic symbol (the Olympic rings) expresses the activity of the Olympic Movement and represents the union of the five continents and the meeting of athletes from around the world at the Olympic Games. But be careful, it is false to say that each of the colors is associated with a specific continent! In fact, when Pierre de Coubertin created the rings in 1913, the five colors associated with the white background represent the colors of the flags of all countries at that time without exception.

¶ Olympic Creed

“The most important thing at the Olympic Games is not to win but to participate, because the important thing in life is not the triumph but the fight; the essential thing is not to have won but to have fought well.”

It is officially from a religious figure that Olympism borrowed its credo, declaimed and displayed during the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games:

“… the important thing in these Olympics is less to win than to take part in them. Let us remember this strong word. It extends across all areas to form the basis of a serene and healthy philosophy. The important thing in life is not the triumph but the fight; the essential thing is not to have won but to have fought well.”

Having become “The important thing is to participate” for the vox populi, this credo has been the subject of real public appropriation which testifies to the diffusion of Olympic values, here selflessness in the accomplishment of the sporting act.

Jacques Rogge and the Internet