© 2005 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ History

Although the site was inhabited as early as the 5th millennium BC, and Egyptian texts make several references to it in the 2nd millennium BC, it was during the Greco-Roman period that Pella flourished. The city’s original name, Pihilum or Pehel, seems to have been changed, according to Stephanus of Byzantium (5th c.), when the city was refounded by Alexander the Great. Alexander Jannaeus captured it, and, being unable to persuade the inhabitants to accept Judaism, destroyed it (Flavius Josephus, BJ I, 4:8; AJ XIII 15:4). Pompey rebuilt it and annexed it to the province of Syria (BJ I, 7:7; AJ XIV, 4:4). It became part of the Decapolis, remaining always a Hellenistic city, and forming part of the northern frontier of Perea (BJ III, 3 3). As part of Agrippa’s kingdom it offered refuge to the budding Christian community of Mount Zion, which under the leadership of Simon took refuge there during the Jewish revolt and the siege of Jerusalem by the Romans (Eusebius HE III, 5; Epiphanius Haer XXIX, 7). When after three years of war and massacres the second Jewish revolt was suppressed by the Romans (132 - 135 AD) and the Emperor Hadrian rebuilt Jerusalem under the new name of Aelia Capitolina, a part of the community living in Pella moved on the orders of the uncircumcised bishop Mark to Mount Zion. In any case, Christianity in Pella persisted, as testified by Ariston (born there in the 2nd century, and author of the Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus) and the discovery of numerous Christian tombs and some inscriptions.

¶ Archaeological ruins

The ruins of Pella can be visited near present-day Tabakat-Fahil, near the Jordan, on the east bank, and approximately at the same height but on the opposite side where Scythopolis or Beth-Shean is located.

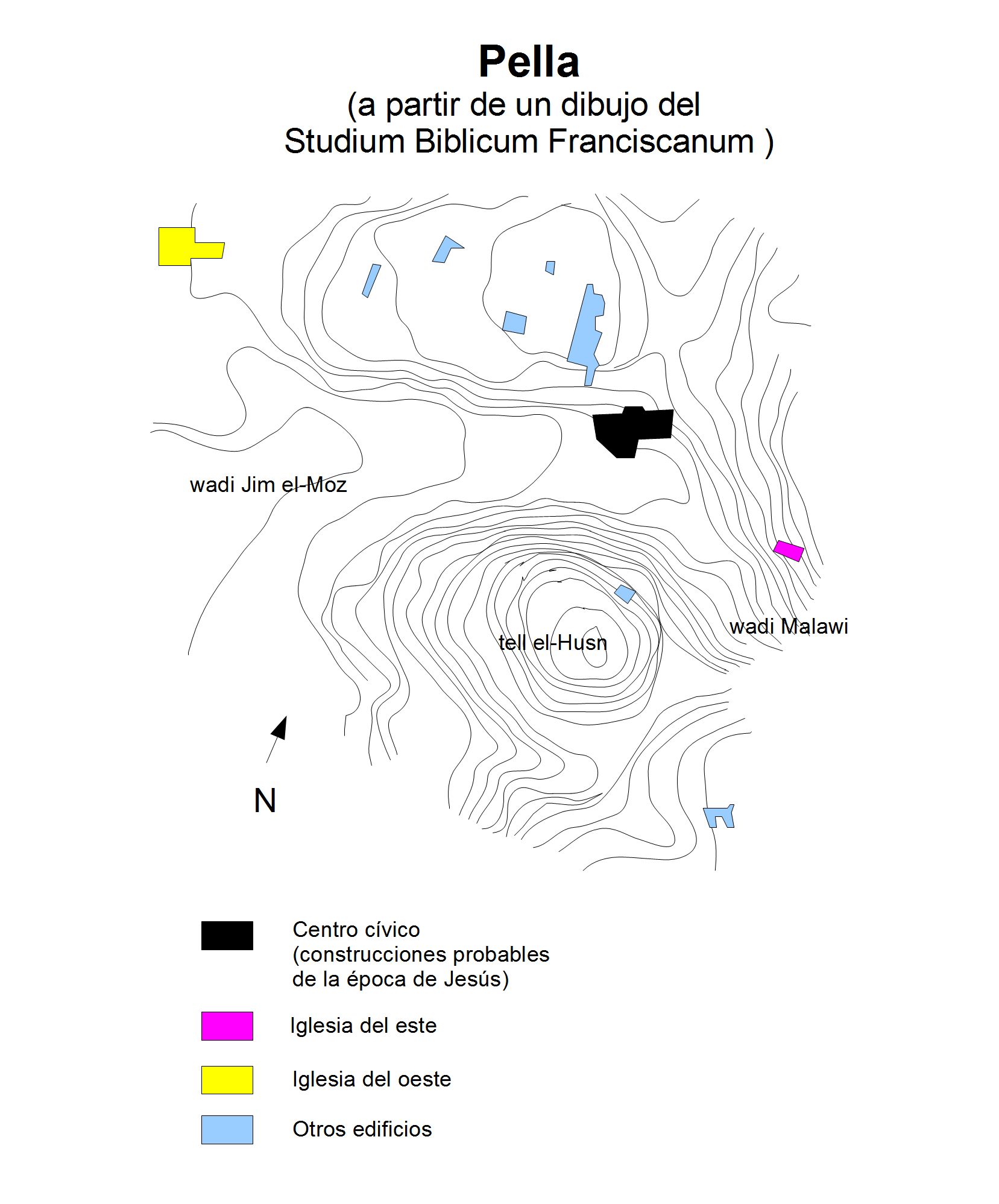

The city was walled between two hills, one not very high to the north, and another more pronounced to the south. Some inscriptions found on coins indicate that a temple may have existed at the top of this latter promontory. These coins reveal the physiognomy of the city in their engraving, showing a main columned cardo, many houses, some on the slope of the hill, and some temples inside.

Two torrents or wadis that surround both hills, the wadi Malawi surrounding the southern hill (called today tell el-Husn), and the wadi el-Hammeh, surrounding the northern hill, were to flow into the central valley where the city extended, called today wadi Jim el-Moz.

There is little in the present ruins that tells us about the time of Jesus in particular. While the temple located at el-Husn has already disappeared and was not replaced by any construction (perhaps the hill was cursed by the presence of that temple), it is nevertheless easy to find remains of the Christian presence (such as several churches) or even Arab (a mosque).

However, there are fairly good remains of some of the Roman buildings from a slightly later period, in what is called the “civic complex”, that is, a series of buildings where the administrative centres of the city were arranged: a temple, a basilica with a well-preserved staircase (later converted into a church in the Byzantine period), a small theatre or odeon built on the southern side of the basilica, and a Roman nympheum or public baths. Right next to these large buildings were the springs with which the city was well supplied.

The excavations, carried out by a team from a university in Sydney, Australia, have yielded little since they began their belated journey in 1983. One of the most notable discoveries has been the remains near an ancient Canaanite temple of large dimensions (32 x 24 m), of the type known as migdol or fortress, dated to around 1600 BC. The work of these excavations has taken archaeologists to the present, so there have been no new finds of interest in the area of the “civic complex” apart from those already visible.

¶ Importance of Pella

That Pella played an essential role in the birth of Christianity is undeniable for scholars. We have substantial evidence that this city was home to a continuous Christian population, had bishops, and had several very ancient churches, the remains of which have survived.

But what perhaps no one finds in the history books is the special relationship that Jesus and his immediate disciples had with this population. If we turn to The Urantia Book, Pella is mentioned as the authentic place where John baptized Jesus (UB 135:8.3), and not the Jordan fords to the south or north that are currently proposed to tourists. Near Pella Jesus spent this period of isolation for forty days (UB 134:7.7), and not in the Judean desert, which is much further south. The first place where Jesus and his disciples stopped for a time to begin their public preaching was near Pella, right where John had camped. In fact, Pella became, much more than Capernaum, the actual center of operations for Jesus’ missionary activity (UB 163:5.1), eventually housing a camp of some five thousand persons, a fully organized tent city (UB 141:1.2). Pella is where Jesus delivered some of his most memorable speeches (UB 170:0.1), where the apostles took refuge after fleeing Jerusalem when Roman troops invaded the country in the 1860s (UB 176:1.5), and finally the place where the Gospel according to Matthew was written (UB 121:8.7). All of this information explains very well why this place eventually became a very important Christian center.

It is curious to note that in the end, the place potentially most suitable for religious tourism has only been turned into a pile of ruins, in favour of other, more dubious places.

¶ References

- Flavius Josephus, Obras completas, Antigüedades judías y Guerras de los Judíos (Complete Works, Jewish Antiquities and Wars of the Jews), (AJ and BJ) Editorial Acervo Cultural, 1961.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History (HE).

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion or Adversus Haereses (Haer).

- Ariston of Pella, Dialogue of Jason and Papiscos (lost text).

- Information from a travel agency.

- Jordan Excursion, including Pella.

- Official website of the Pella excavations.

- Article explaining the discovery of the migdol-type temple at Pella.