© 2006 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

¶ The Sanhedrin of Jerusalem

The Great Sanhedrin of Jerusalem was basically an administrative council made up of seventy members whose functions were primarily legislative (promulgating laws, mostly of a civic-religious nature) and judicial (resolving important legal cases and acting as the Jewish supreme court or beit dyn). But it did not have executive power, which the Jews normally preferred to have in the hands of a legitimate king, something that, however, occurred in only a few periods of Jewish history. The reality is that the Jews never considered their kings to be of much importance because their state was a theocracy, where they considered God to be king, and for this reason the dignitary with the greatest weight for the Jews was the high priest, who was believed to reveal God’s designs in his decisions. So important was this position that at some point the titles of king and high priest were merged into one to give greater prominence to the royal title.

Jewish sages wanted to trace the origin of the Sanhedrin back to a council of seventy elders that Moses supposedly surrounded himself with, but historical data confirm that such a council of seventy elders existed long after Moses and that the reference in Num 11:16 was a later interpolation by the rabbis. Its real origin must be sought in the period of Persian domination, when the Jews enjoyed a certain freedom in their religious affairs, and it was then that a council was organized, made up of nobles or dignitaries (horym or saganym) to decide on religious matters, although nothing is known of its number or organization,and the number of seventy was not yet established.

The Hellenistic influence that the Jewish state received after the Persian period, which normally established two typical democratic institutions as administrative bodies in the cities, the ecclesia or assembly and the boule or council, was not felt as much in Jewish territory. Here, the ancient council of nobles or elders, called at this time the gerousia, still continued in force with full power, since the Greeks also left considerable freedom in internal affairs to their conquered subjects. This gerousia is clearly made up of priests, and their election is not democratic, but hereditary. Only a few priestly families of prominent lineages were part of this council.

In the Roman period, Gabinius (57-55 BC) divided the Jewish territory into five synedria or administrative regions, three of them, Jerusalem, Gazara, and Jericho, located in Judea and under the influence of Jerusalem. It is probably from this period that the council or gerousia of Jerusalem began to be called synedrion, a name that persisted even though only ten years after Gabinius the divisional system of the synedria was dissolved when Caesar handed over the entire territory to the ethnarch Hyrcanus II. The importance of this Jerusalem tribunal is evident from the fact that King Herod, when he took office, had all, or practically all, of its members executed and replaced them with more docile ones.

In the time of Jesus, along with the usual name of synedrion for the Jewish supreme court, the terms presbyterion, gerousia, boule, beit dyn digadol (the great court), sanhedrin gadol (the great sanhedrin), and sanhedrin sl sb ym-w’hd (the sanhedrin of the seventy-one) were also used.

In Jesus’ time, the Sanhedrin was made up of a mix of Sadducees (priests and laymen), aristocrats, and Pharisee sages, and consisted of seventy-one members. This number of seventy-one was common in the administrative councils of many cities of the time. Within the Sanhedrin, there were three categories, from most to least important: the high priests (archiereis), the nobles or aristocrats (archons, bouletes, or dygnatoi), and the wise men or rabbis (grammateis or presbiteroi). The high priests were almost always Sadducees, while the wise men were usually Pharisees. The power of the latter increased over time, especially after the time of Jesus, but in Jesus’ time, both religious parties shared power equally; no group had preeminence in the tribunal. It seems that within the Sanhedrin, the ten most prominent members once served as spokespersons and were called deca protoi, similar to the committee of the same name frequently found in Greek cities.

Nothing at all is known about how a vacant post was filled, but it was certainly not done democratically, as in the Greek councils. Here, members probably held office for life, and new members were elected from among several candidates by vote of the current members. Candidates were required to master rabbinic knowledge and to be pure and legitimate Israelites by birth, and the admission ceremony was the “laying on of hands” (smykt ydyn) or “ordination.” The president of the Sanhedrin, or proedros, who was the high priest, placed his hands on the head of the person admitted and uttered some phrase granting power.

The civil authority of the Sanhedrin of Jerusalem was restricted in Jesus’ time to the eleven toparchies, or regions into which Judea was divided. Therefore, it had no jurisdiction over Jesus while he was in Galilee or other regions. However, it had a high moral influence over the councils and synagogues throughout the Jewish world, although it could not force any institution in its decisions. It was a court competent to make judicial decisions and administrative measures of all kinds, except those within the jurisdiction of higher courts or reserved to the Roman governor. It was not a court of final appeal in case of disagreement with the ruling of a lower court. At that time, appeals did not exist. When a court ruled, its decision was irrevocable. It acted as the supreme court only at the request of a lower court that had failed to decide.

The serious cases reserved for the judgment of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin were those involving the trial of an entire group of people, such as an entire city, or when it came to judging a false prophet or the high priest himself. But in Jesus’ time, the Roman authority was ultimately the enforcer of death sentences in Jewish territory for any of the above cases. A certain degree of independence was common for the lower courts, which could carry out capital punishments in certain cases (for example, an adulterous woman could be stoned to death, as this was a minor case within local jurisdiction). But in the case of Jesus, for example, who was considered a false prophet, he could be sentenced only by the Jerusalem Sanhedrin, but the sentence could not be carried out by him. For these capital cases, Rome had the final say. Augustus had determined in the eastern provinces, by the Fourth Edict of Cyrene (7/6 BC), that capital cases would be reserved for the governor. This was not the norm in the Empire, as in other provinces there was a more even distribution of powers.

The Sanhedrin, therefore, had certain powers to make arrests (it had its own police force), could try criminal cases, and was empowered to carry out lesser sentences that were not capital cases, such as the execution of a religious teacher. Emperor Augustus had promulgated a policy of permissiveness toward all non-degrading religious forms, and the Roman Empire, following this doctrine, protected all religions. The Sanhedrin in Jerusalem, having fallen under Roman jurisdiction, therefore lost the right to suppress religious initiative and coerce religious freedom within its territory.

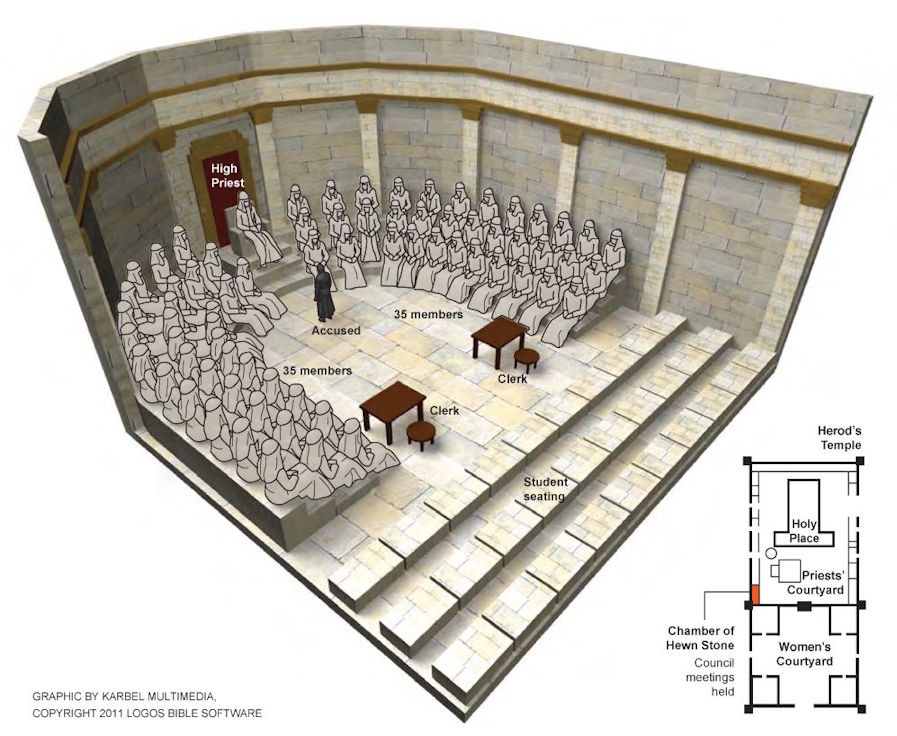

The meetings of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin could not take place on Saturday or the eve of a Sabbath or a holiday, since a verdict could not be passed until the day after the trial. The place where it met, called the bouleyterion or liskat ha-gazyt, was a room whose location is unclear. The Mishnah indicates that it was located within the Temple courtyard, with one half inside and the other outside, but without specifying which part. It was a construction made by normal architectural means, and for this reason it was also called the “Hall of Hewn Stones” or the Hall of the Stones, because it was unusual for the high priests to hold meetings in a place where the stone had been hewn. The Temple was built with unhewn stones. The Talmud mentions that the Sanhedrin moved at some point from the “Hall of Hewn Stones” to another room near a bazaar. This bazaar may have been the one mentioned next to the Xystus, a small square discovered at the foot of Wilson’s Arch. This arch, as is known, is part of a viaduct connecting the upper city with the temple entrance located in the middle of the western wall. The Urantia Book states that at the time of Jesus’ execution the Sanhedrin held its regular meetings in a room within the Temple near the place where the money changers and merchants had their stalls, and was inconvenienced by the clamor and commotion of this marketplace (LU 173:1.5, LU 184:3.2). Perhaps this was the reason that prompted the Sanhedrin to move from the “Hall of Hewn Stones” to the room next to the Xystus. However, if The Urantia Book is correct, this move must have occurred some time after Jesus’ time.

In a trial, the members of the court sat in a semicircle, from which we may assume that the “Hall of Carved Stones” had seats in the shape of a “C.” In front sat the two court clerks, who recorded the accusations and the arguments in favor of the accused. Behind them were three rows of seats where the rabbinical students could sit and listen to the proceedings. The accused had to adopt a humble posture, wear their hair loose, and wear black clothing. First, the arguments in favor were presented and witnesses who spoke favorably of the defendant were brought in, then the opposing side was heard. In capital cases, the students, who were allowed to ask questions, could only speak in favor of the defendant, but not against him. In all other cases, they could speak in defense of or against the prisoner. Acquittals could be handed down on the day of the trial. A simple majority vote was sufficient in this case. A conviction required a majority of at least two in the lower courts, which were made up of twenty-three members, but in the case of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin, which had seventy-one members, there was no possibility of a tie. A simple majority determined the verdict.

¶ Other Lower Courts

The Jerusalem Sanhedrin could not handle every case that might arise, since it was only one court, so it was logical that it relied on the support of other lower courts to which it delegated some of its functions. Specifically, mention is made of the existence in Jerusalem of two other lower courts called “the court of the Temple Mount Gate” in the first instance, and then the court of the “Temple Court” in the second instance. If neither of them achieved unanimous decision in a given case, then it was lawful to bring the case before the supreme court.

The larger cities of the Jewish territory all had minor courts or sanhedrins (sanhedrins qtnh), made up of twenty-three members and with jurisdiction over certain types of cases, including some capital cases. For example, they could execute an adulteress. The Jerusalem Sanhedrin was therefore competent for the cases already discussed and for cases occurring in Jerusalem and its surrounding villages that the city’s minor courts had been unable to rule on. It is possible that the larger Jewish capitals even had courts made up of seventy-one members. These courts or councils were constituted in the same way as the one in Jerusalem, and their functions, constitution, and procedures must have been similar, with the exception that all of them were limited in certain cases to the supreme court in Jerusalem.

¶ The influence of Jewish institutions on the Jesus movement

It should not be assumed that Jesus’ intention in creating his evangelical movement was to form the Christian institution as we see it today. Christianity is much more pagan and Gentile than what Jesus initially organized. A study of the Gospels reveals an influence of the Jewish organization of that time in the way Jesus’s nascent movement was organized:

- Jesus formed a group of twelve prominent disciples, to whom he gave the title of apostles, a non-Jewish word of Greek origin, designating a royal messenger or envoy. Curiously, the number twelve, of great Jewish significance, imitates a council of twelve prominent men that apparently existed in ancient Judaism when there were twelve tribes. Each man was the highest representative of each tribe. Apparently, Jesus’ followers saw this number twelve as a symbol in this sense. They believed that Jesus closed the number at twelve because they believed the apostles would act as representatives of the twelve tribes of Israel when the world reached its fullness at the immediate end of time. However, the end of the world did not come, and the emphasis of Christian organization shifted from East to West. At that time, the number of apostles did not seem appropriate to limit to twelve in a Roman setting. Today, the synod of bishops, the current equivalent of Jesus’ twelve apostles, evidently does not present this limitation.

- The procedure by which Jesus invests his twelve outstanding disciples as apostles is the same rite of “laying on of hands” (smykt ydyn) or “ordination” that was already practiced by the members of the Sanhedrin in his time. This ceremony has continued to this day. Christianity modified it from its original Jewish meaning, considering it the rite by which the Holy Spirit was communicated. But it would be worth analyzing whether Jesus truly practiced the “laying on of hands” as a customary rite and because he wanted his followers to continue the same practice, or whether it was a rite performed very occasionally and to mark special moments without the intention of instituting any specific ritual (LU 140:0.3, LU 140:2.1, LU 163:1.3). From reading The Urantia Book one gets the feeling that Jesus never attached much importance to the ways and means of performing rituals, and I doubt that, as some scholars point out, this rite of “laying on of hands” was something habitual for him.

- Jesus organized a group of seventy evangelists, that is, disciples commissioned to evangelize, who worked for several months under the direction of the twelve apostles (Luke 10:1-24). This number also seems to follow the example of the Jewish high courts, which were made up of a similar number of members. Even the designation of some members of the Sanhedrin (presbyters, for example) was retained in the Christian church. But did Jesus appoint seventy evangelists because this number represented some special criterion, or was it simply a coincidence? The Urantia Book makes the answer to this question very clear (LU 163:4.17)

- The way in which Acts 1:21-26 the designation of Matthias as Judas’s successor is told to us also seems to follow a Jewish way of thinking. It was not done in a democratic way, but rather a lot was drawn. The Jews considered “casting lots” a way of consulting the divine plan. It seems that the mode of succession within the group of apostles followed the line of the Sanhedrins.

¶ External links

¶ References

-

Emil Schürer, Historia del pueblo judío en tiempos de Jesús (History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus), Ediciones Cristiandad, 1985, pp. 269-304.

-

The “Place of the Trumpeting” and the place above the Xystus reveal the real location of the Temple