© 2020 Jean Annet

© 2020 Association Francophone des Lecteurs du Livre d'Urantia

In 2003, JeanMarie Chaise completed, after 7 years of effort, the translation of the Urantia Book into Esperanto.

During an email exchange, during our very first UBIS URANTIA course on the Internet with JeanMarie, we shared our common passion for this universal language. He then sent me his translation of the book into Esperanto, telling me that he had to undergo medical examinations and that we would discuss it again afterwards. Unfortunately, he never left the hospital.

So I received his translation as a testament, as a work that he passed on to me.

Very quickly I created a website to finalize this translation into Esperanto, by putting in the fields to deposit the translations in the different languages, paragraph by paragraph, introducing a glossary with the new words to translate, etc, etc…

But the task was enormous and my schedule did not allow me to devote myself to it as much as I would have liked.

This translation then remained in drawers for years.

Now, having recently retired, I can finally return to work and finish my work.

In addition, little by little an international team is being set up to correct the translation of the book. The team includes a Brazilian, a Quebecer, a Frenchman and two Belgians (one Flemish and one Walloon).

Why Esperanto?

One might ask: why translate the book into Esperanto. What will it be used for and, above all, to whom?

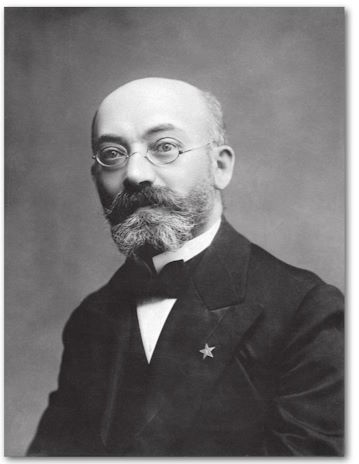

Without giving a long explanation of this universal language, we could say that it was created by a Pole at the beginning of the 20th century. In his youth, he had been very disturbed by the different communities in his village who could not get along (Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, etc.). He therefore decided to create a common language from the different European languages so that all these people could communicate with each other. In fact, what he wanted above all was to promote human brotherhood. And since he was a believer, as a Jew, he was convinced that if all men on Earth were brothers, they could only come from one Father and that there was only one God.

Within Esperanto, there was this internal idea (la interna ideo) of the Human Brotherhood under the Fatherhood of God. If all Esperantists accept the idea of the Human Brotherhood, it is not the same for the Fatherhood of God, but “la interna ideo” is underlying in the language and all Esperantists know it. The Esperanto world is therefore an ideal “target” audience to transmit the teachings of The Urantia Book. We would no longer communicate the book to a nation in its language, but to a type of population on a global level, which has the same ideal.

Esperanto and The Urantia Book have strangely many similarities between them:

- They both start at the beginning of the 20th century

- They do not belong to anyone, to any people, any nation, any association, any religion.

- They only spread thanks to their “users”

- To the outside world, they are not credible

- Esperanto is far replaced by English and is therefore not necessary

- The Urantia Book is not “credible”, we do not know who wrote it or where it comes from. And Christianity is the majority religion on earth. There is no need to have a new religion with the teachings of Jesus.

- They both have their opponents and their staunch supporters.

- They both organize national meetings and international congresses

- They are both ahead of their time and will only come into their own in the future.

It is difficult for everyone to determine their number of followers. There are those who are absolutely convinced of it (who speak it, who read it, who study it). There are those who approach them from further away and there are those who know that it exists.

I could also say that this project of translating The Urantia Book into Esperanto goes in the direction of Light and Life.

No evolutionary world can hope to progress beyond the first stage of anchoring in the light without having rallied to a single language, a single religion, a single philosophy. UB 55:3.22

The Urantia Book in Esperanto is the universal religion in the universal language.

The philosophy of Esperanto was explained by its founder as “Homaranismo”, i.e. belonging to a single humanity, without distinction of sex, race, ethnicity, people, language or religion.

It should also be noted that there has already been a Face Book page in Esperanto on The Urantia Book for several years and that this page uses different translations that were started by one or the other of the team. It is therefore urgent to harmonize the translation so that there is only one official text used by all Esperanto users.

Currently the translation of the book into Esperanto is relatively good. It was reviewed by Jean Royer, who was an Esperantist, and partly by a Togolese Esperantist grammarian. All the terms, neologisms and new words must be harmonized and the entire translation reviewed paragraph by paragraph. The Foundation has given its agreement in principle for this correction of the book to begin.

Doctor Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, known in French as Louis-Lazare Zamenhof, was a Polish ophthalmologist born on December 15, 1859 in Biatystok in the Russian Empire and died on April 14, 1917 in Warsaw. Born into a Jewish family, his languages of use were Yiddish, Russian and Polish.

Esperanto is an international constructed language used as a lingua franca by people from at least 120 countries around the world, including as their mother tongue. Not being the official language of any state, Esperanto allows a neutral bridge to be established between cultures; some speakers call “Esperantia” the linguistic zone formed by the geographical locations where they are located. Requiring a short learning period to be usable, Esperanto is thus presented as an effective and economically equitable solution to the problem of communication between people of different mother tongues. (Source Wikipedia)

In a few years, there will be a new translation of the book: LA URANTIA LIBRO.

John ANNET

Louis-Lazare Zamenhof: Inventor of Esperanto. He was a linguist, ophthalmologist, inventor, poet, translator, Esperantist, doctor, medical writer, translator of the Bible, Esperantologist (Photo and source Wikipedia)

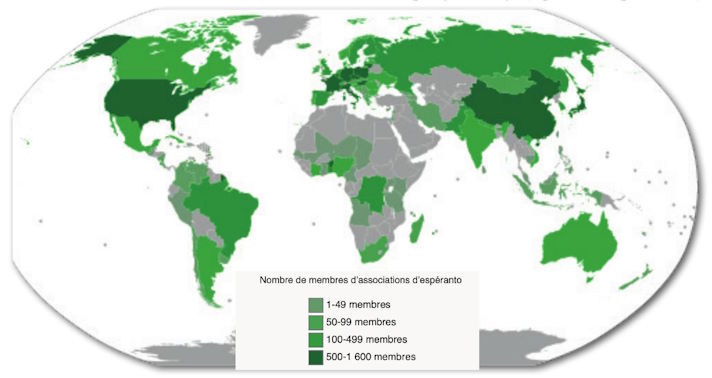

The number of Esperanto speakers is difficult to estimate. Estimates vary between one hundred thousand and ten million. Two million is the most commonly used number, or even up to three million. However, it can be said that in 2015 there are 120 countries in which there are Esperanto speakers.

Esperantia (Esperanto: Esperantujo) is the name given to the linguistic area corresponding to the countries of the world where there are Esperanto speakers, a total of at least 120 countries 1 of the world, even if it has no political form2 or dedicated territory on the surface of the Earth; similarly, the group of French-speaking countries is called “Francophonie”. By extension, Esperantia also designates the culture generated by the millions of Esperanto speakers, as well as the places and institutions where the language is used.