© 1994 Ken Glasziou

© 1994 The Brotherhood of Man Library

Because of the mandatory restrictions imposed on the revelators[1], the science and cosmology of The Urantia Book is at the approximate level of current human knowledge for the mid-1930’s. It also contains some statements that were prophetic at that time because the mandate allowed the revelators to supply vital information to fill gaps in our otherwise earned knowledge. One such gap-filler may have been:

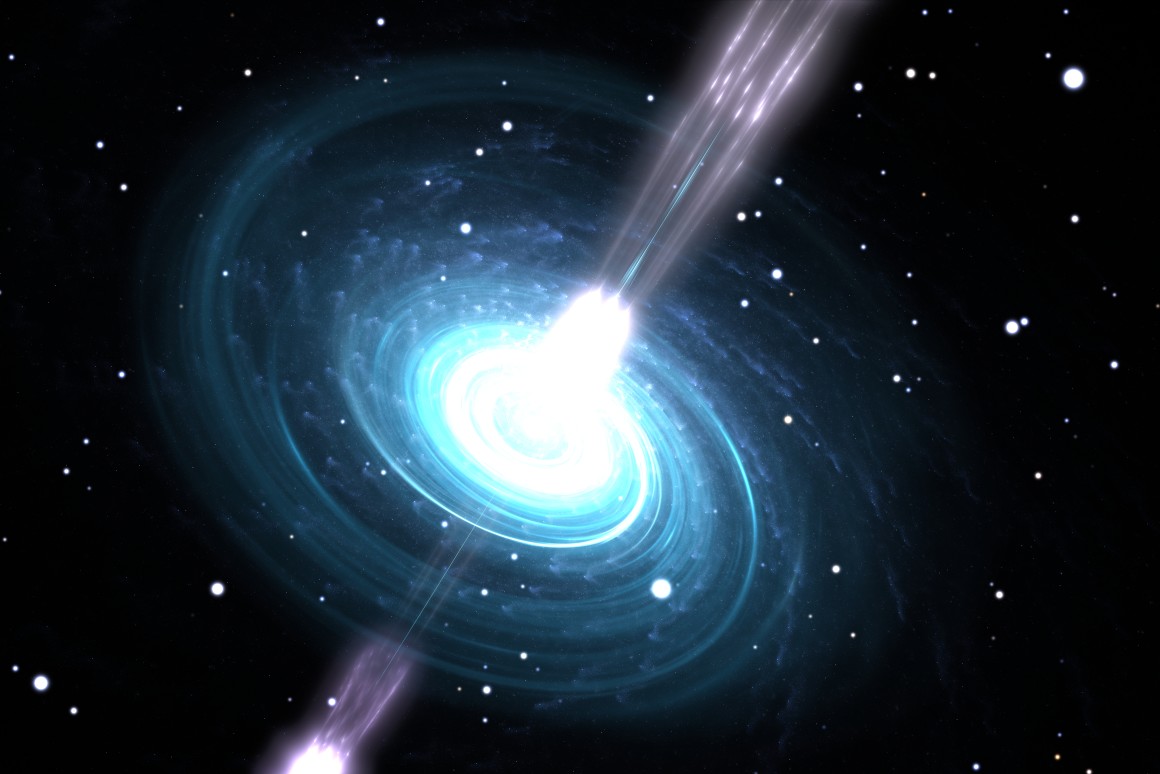

In large suns—small circular nebulae—when hydrogen is exhausted and gravity contraction ensues, if such a body is not sufficiently opaque to retain the internal pressure of support for the outer gas regions, then a sudden collapse occurs. The gravity-electric changes give origin to vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential, and such particles readily escape from the solar interior, thus bringing about the collapse of a gigantic sun within a few days. . . . [2]

No tiny particles devoid of electric potential that could escape readily from the interior of a collapsing star were known to exist in 1934. In fact, the reality of such particles were not confirmed until 1956, one year after the publication of The Urantia Book. The existence of particles that might have such properties had been put forward as a suggestion by Wolfgang Pauli[3] in 1932, because studies on radioactive beta decay of atoms had indicated that a neutron could decay to a proton and an electron, but measurements had shown that the combined mass energy of the electron and proton did not add up with that of the neutron. To account for the missing energy, Pauli suggested a little neutral particle was emitted, and then, on the same day, while lunching with the eminent astrophysicist Walter Baade[4], Pauli commented that he had done the worst thing a theoretical physicist could possibly do, he had proposed a particle that could never be discovered because it had no properties. Not long after, the great Enrico Fermi[5] took up Pauli’s idea and attempted to publish a paper on the subject in the prestigious science journal Nature. The editors rejected Fermi’s paper on the grounds that it was too speculative. This was in 1933, the year before receipt of the relevant Urantia Paper.

An interesting thing to note is The Urantia Book statement that tiny particles devoid of electric potential would be released in vast quantities during the collapse of the star. If, in 1934, an author other than a knowledgeable particle physicist was prophesying about the formation of a neutron star (a wildly speculative proposal from Zwicky and Baade in the early 1930’s), then surely that author would have been thinking about the reversal of beta decay in which a proton, an electron and Pauli’s little neutral particle would be squeezed together to form a neutron.

Radioactive beta decay can be written:

neutron ⟶ proton + electron + LNP

where LNP stands for little neutral particle.

Hence the reverse should be:

LNP + electron + proton ⟶ neutron

For this to occur an electron and a proton have to be compressed to form a neutron but somehow they would have to add a little neutral particle in order to make up for the missing mass-energy. Thus, in terms of available speculative scientific concepts in 1934, The Urantia Book appears to have put things back to front, it has predicted a vast release of LNP’s, when the reversal of radioactive beta decay would appear to demand that LNPs should disappear.

The idea of a neutron star was considered to be highly speculative right up until 1967. Most astronomers believed that stars of average size, like our sun, up to stars that are very massive, finished their lives as white dwarfs. The theoretical properties of neutron stars were just too preposterous; for example, a thimble full would weigh about 100 million tonnes. A favored alternative proposal was that large stars were presumed to blow off their surplus mass a piece at a time until they got below the Chandrasekhar limit[6] of 1.4 solar masses, when they could retire as respectable white dwarfs. This process did not entail the release of vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential that accompany star collapse as described in the cited Urantia Book quotation.

Distinguished Russian astrophysicist, Igor Novikov[7], has written, “Apparently no searches in earnest for neutron stars or black holes were attempted by astronomers before the 1960s. It was tacitly assumed that these objects were far too eccentric and most probably were the fruits of theorists wishful thinking. Preferably, one avoided speaking about them. Sometimes they were mentioned vaguely with a remark yes, they could be formed, but in all likelihood this had never happened. At any rate, if they existed, then they could not be detected.”[8]

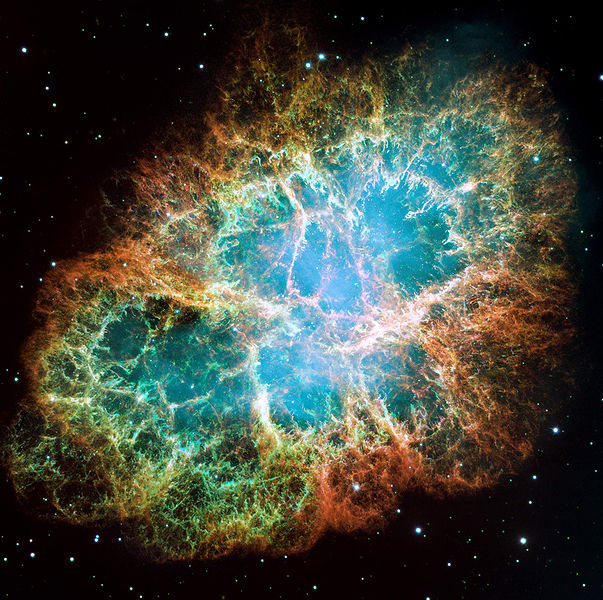

Acceptance of the existence of neutron stars gained ground slowly with discoveries accompanying the development of radio and x-ray astronomy. The Crab nebula played a central role as ideas about it emerged in the decade, 1950-1960. Originally observed as an explosion in the sky by Chinese astronomers in 1054, interest in the Crab nebula increased when, in 1958, Walter Baade reported visual observations suggesting moving ripples in its nebulosity. When sensitive electronic devices replaced the photographic plate as a means of detection, the oscillation frequency of what was thought to be a white dwarf star at the center of the Crab nebula turned out to be about 30 times per second.

For a white dwarf star with a diameter in the order of 1000 km, a rotation rate of even once per second would cause it to disintegrate due to centrifugal forces. Hence, this remarkably short pulsation period implied that the object responsible for the light variations must be very much smaller than a white dwarf, and the only possible contender for such properties appeared to be a neutron star. Final acceptance came with pictures of the center of the Crab nebula beamed back to earth by the orbiting Einstein X-ray observatory in 1967. These confirmed and amplified the evidence obtained by prior observations made with both light and radio telescopes.

The reversal of beta-decay, as depicted in (2) above, involves a triple collision, an extremely improbable event, unless two of the components combine in a meta-stable state—a fact not likely to be obvious to a non-expert observer which also indicates that the author(s) of the Urantia Paper was highly knowledgeable in this field.

The probable evolutionary course of collapse of massive stars has only been elucidated since the advent of fast computers. Such stars begin life composed mainly of hydrogen gas that burns to form helium. The nuclear energy released in this way holds off the gravitational urge to collapse. With the hydrogen in the central core exhausted, the core begins to shrink and heat up, making the outer layers expand. With the rise in temperature in the core, helium fuses to give carbon and oxygen, while the hydrogen around the core continues to make helium. At this stage the star expands to become a red giant.

After exhaustion of helium at the core, gravitational contraction again occurs and the rise in temperature permits carbon to burn to yield neon, sodium, and magnesium, after which the star begins to shrink to become a blue giant. Neon and oxygen burning follow. Finally silicon and sulphur, the products from burning of oxygen, ignite to produce iron. Iron nuclei cannot release energy on fusing together, hence with the exhaustion of its fuel source, the furnace at the center of the star goes out. Nothing can now slow the onslaught of gravitational collapse, and when the iron core reaches a critical mass of 1.4 times the mass of our sun, and the diameter of the star is now about half that of the earth, the star’s fate is sealed.

Within a few tenths of a second, the iron ball collapses to about 50 kilometers across and then the collapse is halted as its density approaches that of the atomic nucleus and the protons and neutrons cannot be further squeezed together. The halting of the collapse sends a tremendous shock wave back through the outer region of the core.

The light we see from our sun comes only from its outer surface layer. However, the energy that fuels the sunlight (and life on earth) originates from the hot, dense thermonuclear furnace at the Sun’s core. Though sunlight takes only about eight minutes to travel from the sun to earth, the energy from the sun’s core that gives rise to this sunlight takes in the order of a million years to diffuse from the core to the surface. In other words, a sun (or star) is relatively “opaque” (as per The Urantia Book[2:1]) to the energy diffusing from its thermonuclear core to its surface, hence it supplies the pressure necessary to prevent gravitational collapse. But this is not true of the little neutral particles, known since the mid 1930’s by the name neutrinos. These particles are so tiny and unreactive that their passage from our sun’s core to its exterior takes only about 3 seconds.

It is because neutrinos can escape so readily that they have a critical role in bringing about the star’s sudden death and the ensuing explosion. Neutrinos are formed in a variety of ways, many as neutrino-antineutrino pairs from highly energetic gamma rays and others arise as the compressed protons capture an electron (or expel a positron) to become neutrons, a reaction that is accompanied by the release of a neutrino. Something in the order of 1057 electron neutrinos are released in this way. Neutral current reactions from Zo particles of the weak force also contribute electron neutrinos along with the ‘heavy’ muon and tau neutrinos.

Together, these neutrinos constitute a “vast quantity of tiny particles devoid of electric potential” that readily escape from the star’s interior. Calculations indicate that they carry ninety-nine percent of the energy released in the final supernova explosion. The gigantic flash of light that accompanies the explosion accounts for only a part of the remaining one percent! Although the bulk of the neutrinos and anti-neutrinos are released during the final explosion, they are also produced at the enormous temperatures reached by the inner core during final stages of contraction.

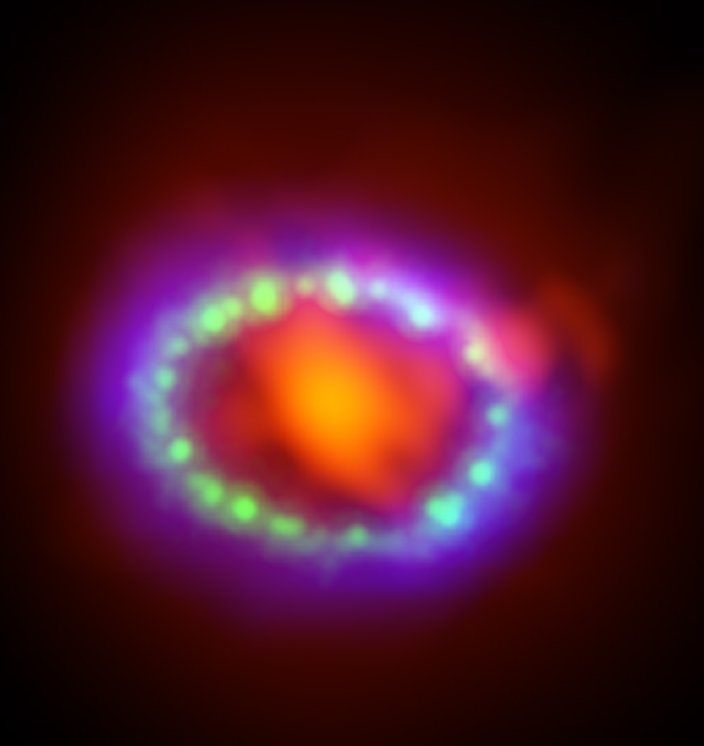

The opportunity to confirm the release of the neutrinos postulated to accompany the spectacular death of a giant star came in 1987 when a supernova explosion, visible to the naked eye, occurred in the Cloud of Magellan that neighbors our Milky Way galaxy. Calculations indicated that this supernova, dubbed SN1987A[9], should give rise to a neutrino burst at a density of 50 billion per square centimeter when it finally reached the earth, even though expanding as a spherical ‘surface’ originating at a distance 170,000 light years away. This neutrino burst was observed in the huge neutrino detectors at Kamiokande in Japan and at Fairport, Ohio, in the USA. lasting for a period of just 12 seconds, and confirming the computer simulations that indicated they should diffuse through the dense core relatively slowly. From the average energy and the number of ‘hits’ by the neutrinos in the detectors, it was possible to estimate that the energy released by SN1987 amounted to 2-3 x 1053 ergs. This is equal to the calculated gravitational binding energy that would be released by the collapse of a core of about 1.5 solar masses to a neutron star. Thus SN1987A provided a remarkable confirmation of the general picture of neutron star formation developed over the last fifty years. Importantly, it also confirmed that The Urantia Book had its facts right long before the concept of neutrino-spawning neutron stars achieved respectability.

¶ Hypotheses on the possible origins of the Urantia Paper’s statement on solar collapse

For the mid-thirties the description in the paper 41 of The Urantia Book was quite a statement[2:2]. These tiny particles that we now call neutrinos were entirely speculative in the early 1930’s and were required to account for the missing mass-energy of beta radioactive decay.

In the early 1930’s, the idea that supernova explosions could occur and result in the formation of neutron stars was extensively publicized by Fritz Zwicky[10] of the California Institute of Technology (Caltec) who worked in Professor Millikan’s Dept[11]. For a period during the mid-thirties, Zwicky was also at the University of Chicago. Dr. Sadler[12] is said to have known Millikan. So alternative possibilities for the origin of The Urantia Book quote above could be:

- The revelators followed their mandate and used a human source of information about supernovae, possibly Zwicky.

- Dr Sadler had learned about the tiny particles devoid of electric potential from either Zwicky, Millikan, or some other knowledgeable person and incorporated it into The Urantia Book.

- It is information supplied to fill missing gaps in otherwise earned knowledge as permitted in the mandate.[13]

Zwicky had the reputation of being a brilliant scientist but given to much wild speculation, some of which turned out to be correct. A paper published by Zwicky and Baade in 1934 proposed that neutron stars would be formed in stellar collapse and that 10% of the mass would be lost in the process. [14]

In Black Holes and Time Warps. Einstein’s 'v Outrageous Legacy[15], a book that covers the work and thought of this period in detail, K. S . Thorne, Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltec, writes:

In the early 1930’s, Fritz Zwicky and Walter Baade joined forces to study novae, stars that suddenly flare up and shine 10,000 times more brightly than before. Baade was aware of tentative evidence that, besides ordinary novae, there existed superluminous novae. These were roughly of the same brightness but since they were thought to occur in nebulae far out beyond our Milky Way, they must signal events of extraordinary magnitude. Baade collected data on six such novae that had occurred during the current century.

As Baade and Zwicky struggled to understand supernovae, James Chadwick, in 1932, reported the discovery of the neutron. This was just what Zwicky required to calculate that if a star could be made to implode until it reached the density of the atomic nucleus, it might transform into a gas of neutrons, reduce its radius to a shrunken core, and, in the process, lose about 10 % of its mass. The energy equivalent of the mass loss would then supply the explosive force to power a supernova.

Zwicky believed cosmic rays accounted for the mass energy loss in supernova explosions

Information, extracted from Thorne’s recent book, indicates that Zwicky knew nothing about the possible role of “little neutral particles” in the implosion of a neutron star, but rather that he attributed the entire mass-energy loss to cosmic rays. So, if not from Zwicky, what then is the human origin of The Urantia Book’s statement that the neutrinos escaping from its interior bring about the collapse of the imploding star? (Current estimates attribute about 99% of the energy of a supernova explosion to being carried off by the neutrinos).

In his book, Thorne further states: “astronomers in the 1930’s responded enthusiastically to the Baade-Zwicky concept of a supernova, but treated Zwicky’s neutron star and cosmic ray ideas with disdain. . . . In fact it is clear to me from a detailed study of Zwicky’s writings of the era that he did not understand the laws of physics well enough to be able to substantiate his ideas.” This opinion was also held by Robert Oppenheimer[16] who published a set of papers with collaborators Volkoff, Snyder, and Tolman, on Russian physicist Lev Landau’s[17] ideas about stellar energy originating from a neutron core at the heart of a star.

¶ Einstein and Eddington opposed neutron star concept

These Oppenheimer papers concluding that either neutron stars or black holes could be the outcome of massive star implosion were about as far as physicists could go at that time. However, the most prominent physicist of the time, Albert Einstein[18], and the doyen of astronomers, Sir Arthur Eddington[19], both vigorously opposed the concepts involved in stellar collapse beyond the white dwarf stage. Thus the subject appears to have been put on hold coincident with the outbreak of war in 1939.

During the 1940’s, virtually all capable physicists were occupied with tasks relating to the war effort. Apparently this was not so for Russian-born astronomer-physicist, George Gamow[20], a professor at Leningrad who had taken up a position at George Washington University in 1934. Gamow conceived the beginning of the Hubble expanding universe as a thermonuclear fireball in which the original stuff of creation was a dense gas of protons, neutrons, electrons, and gamma radiation which transmuted by a chain of nuclear reactions into the variety of elements that make up the world of today. Referring to this work, Overbye[21] writes: “In the forties, Gamow and a group of collaborators wrote a series of papers spelling out the details of thermonucleogenesis. Unfortunately their scheme didn’t work. Some atomic nuclei were so unstable that they fell apart before they could fuse again into something heavier, thus breaking the element building chain. Gamow’s team disbanded in the late 40’s, its work ignored and disdained.” Among this work was a paper by Gamow and Schoenfeld that proposed that energy loss from aging stars would be mediated by an efflux of neutrinos. This proposal appears to have been overlooked or ignored until the 1960’s.

¶ Conservation of energy law under fire

As time went by, the need for the neutrino grew, firstly to save the law of conservation of energy, but also laws of conservation of momentum, angular momentum (spin), and lepton number. As knowledge of what it ought to be like grew, plus the knowledge accruing from the intense efforts to produce the atom bomb, possible means of detecting this particle began to emerge. In 1953, experiments were begun by a team led by C.L. Cowan and F. Reines.[22] Fission reactors were now in existence in which the breakdown of uranium yielded free neutrons that, outside of the atomic nucleus, were unstable and broke down via beta decay to yield a proton, an electron, and, if it existed, the missing particle.

¶ Detection of the elusive neutrino

The Cowan and Reines team devised an elaborate scheme to detect the antineutrinos from a reactor. By 1956 their system was detecting 70 such events per day, unequivocally ascribable to antineutrinos. It now remained to prove that this particle was not its own antiparticle, as is the case with the photon. This was done by R.R. Davis[23] in 1956, using a detection system designed specifically for what the properties of the neutrino should be and testing it with an antineutrino source from a fission reactor.

¶ Renewal of the search for the neutron star

The subject of the fate of imploding stars re- opened with vigor when both Robert Oppenheimer and John Wheeler[24], two of the really great names of physics, attended a conference in Brussels in 1958. Oppenheimer believed that his 1939 papers said all that needed to be said about such implosions. Wheeler disagreed, wanting to know what went on beyond the well-established laws of physics.

When Oppenheimer and Snyder did their work in 1939, it had been hopeless to compute the details of the implosion. In the meantime, nuclear weapons design had provided the necessary tools because, to design a bomb, nuclear reactions, pressure effects, shock waves, heat, radiation, and mass ejection had to be taken into account. Wheeler realized that his team had only to rewrite their computer programs so as to simulate implosion rather than explosion. However his hydrogen bomb team had been disbanded and it fell to Stirling Colgate[25] at Livermore, in collaboration with Richard White and Michael May, to do these simulations. Wheeler learned of the results and was largely responsible for generating the enthusiasm to follow this line of research. The term black hole was coined by Wheeler.

The theoretical basis for supernova explosions is said to have been laid by E. M. Burbidge, G.R. Burbidge, W. A. Fowler, and Fred Hoyle in a 1957 paper[26]. However, even in Hoyle and Narlikar’s text book, The Physics-Astronomy Frontier (1980)[27], no consideration is given to a role for neutrinos in the explosive conduction of energy away from the core of a supernova. In their 1957 paper, Hoyle[28] and his co-workers proposed that when the temperature of an aging massive star rises to about 7 billion degrees K, iron is rapidly converted into helium by a nuclear process that absorbs energy. In meeting the sudden demand for this energy, the core cools rapidly and shrinks catastrophically, implodes in seconds, and the outer envelope crashes into it. As the lighter elements are heated by the implosion they burn so rapidly that the envelope is blasted into space. So, two years after the first publication of The Urantia Book, the most eminent authorities in the field of star evolution make no reference to the “vast quantities of tiny particles devoid of electric potential” that the book says escape from the star interior to bring about its collapse. Instead they invoke the conversion of iron to helium, an energy consuming process now thought not to be of significance.

Following on from the forgotten Gamow and Schoenfeld paper, the next suggestion that neutrinos may have a role in supernovae came from Ph.D. student, Hong-Yee Chiu[29], working under Philip Morrison[30]. Chiu proposed that towards the end of the life of a massive star, the core would reach temperatures of about 3 billion degrees at which electron-positron pairs would be formed and a tiny fraction of these would give rise to neutrino- antineutrino pairs. Chiu speculated that X-rays would be given off by the star for about 1000 years and that the temperature would ultimately reach about 6 billion degrees when an iron core would form at the central region of the star. The flux of neutron-antineutrino pairs would then be sufficiently great to carry off the explosive energy of the star in a single day. The 1000-year period predicted by Chiu for X-ray emission was reduced to about one year by later workers. Chiu’s proposals appear to have been first published in a Ph. D. thesis submitted at Cornell University in 1959. Scattered references to it are made by Philip Morrison[31] and by Isaac Asimov[32].

¶ No neutral current, no supernova

Dennis Overbye, in his book Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos[21:1] records that, for supernovae, almost all the energy of the inward free fall comes out in the form of neutrinos. The success of this scenario (as proposed by Chiu) depends on a feature of the weak interaction called the neutral currents[33]. Without this, the neutrinos do not supply enough ‘oomph’ and theorists had no good explanation for how stars explode. In actuality the existence of the neutral current for the weak interaction was not demonstrated until the mid 1970’s.

A 1985 paper (Scientific American) by Hans A. Bethe[34] and Gerald Brown[35] entitled How a Supernova Explodes shows that understanding of the important role of the neutrinos was well advanced by that time. These authors attribute this understanding to the computer simulations of W. David Arnett of the University of Chicago and Thomas Weaver and Stanford Woosley of the University of California at Santa Cruz.

In a recent report in Sky and Telescope (August, 1995) it is stated that, during the past decade, computer simulations of supernovas have bogged down at 100 to 150 km from the center and failed to explode. These models were one dimensional. With more computer power becoming available, two dimensional simulations have now been carried out and model supernova explosions produced. The one reported was for a 15 solar mass supernova that winds up as a neutron star. However the authors speculate that at least some 5 to 15 solar mass implosions might wind up as black holes. There is still a long way to go in understanding the details of stellar implosions.

¶ Who dunit? Paring away the alternatives

Referring to our three alternatives to explain how the reference to the role of the tiny uncharged particles in supernova explosions got to be in the Urantia Papers, ostensibly in 1934, our investigation showed that Zwicky is unlikely to have been the source as he firmly believed X-rays, not neutrinos, accounted for the 10% mass loss during the death of the star.

Remembering that neutron stars were not demonstrated to exist until 1967, that some of the biggest names in physics and astronomy were totally opposed to the concept of collapsing stars (Einstein, Eddington), and that, well into the 1960’s, the majority of astronomers assumed that massive stars shed their bulk piecemeal prior to retiring respectably as white dwarfs, it appears that it would have been a preposterous notion to attempt to support the reality of a revelation by means of speculation about the events occurring in massive star implosion at any time prior to the 1960’s. If it is assumed that, on what would have needed to be the expert advice of a knowledgeable but reckless astrophysicist, Dr Sadler wrote the material into the Urantia paper 41 subsequent to the concepts on neutrinos appearing in the Gamow et al. publications, then it becomes necessary to ask why was it not removed when that work lost credibility later in the 1940’s?–and particularly so since, in their conclusions, Gamow ad Schoenberg drew attention to the fact that, “the neutrinos are still considered as highly hypothetical particles because of the failure of all efforts to detect them,” as well as noting that “the dynamics of the collapse represents very serious mathematical difficulties.”

¶ Printing Plates for The Urantia Book

As a result of the Maaherra affair[36], documentary evidence has come to light to show that acceptance of the contract to prepare the metal printing plates from the manuscript of the Urantia Papers occurred in September, 1941. Printing technology of the time required a separate metal plate for each individual page. Hence, deletions, additions, and alterations that carried through to other pages could be enormously expensive and were avoided if at all possible.

It has already been indicated that the highly speculative 1942 paper of Gamow and Schoenberg was unlikely to have been the source of the book’s statement on star implosion. The new evidence regarding printing plates makes it even more unlikely.

¶ Invoking Occam’s Razor

The language, level of knowledge, and the terminology of the paper 41 reference (UB 41:8.3), together with the references to the binding together of protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus, the two types of mesotron, and the involvement of small uncharged particles in beta radioactive decay as described on UB 42:8.5-7, is that of the early 1930 period, and not that of the 40’s and 50’s. It is what would be expected from authors constrained by a mandate not to reveal unearned knowledge except in special circumstances. Applying the Occam’s razor principle of giving preference to the simplest explanation consistent with the facts, we must conclude that the most probable explanation for the prophetic material of UB 41:8.3 is that it is original to the Urantia Papers as received in 1934 and therefore comes into the category nominated in the revelatory mandate as key information supplied to fill missing gaps in our knowledge. At present, I do not believe that there is a satisfactory explanation for this statement from The Urantia Book in terms of attributing it to a human author.

¶ Links

¶ External links

- This report groups together two articles published in Innerface International newsletter, available in Urantia Fellowship website:

Vol. 1 No. 6, Nov/Dec 1994: https://urantia-book.org/archive/newsletters/innerface/vol1_6/page15.html

Vol. 3 No. 2, March/April 1996: https://urantia-book.org/archive/newsletters/innerface/vol3_2/page12.html

¶ References

Sutton, C. Spaceship Neutrino. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992)

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli (1900-1958) was a Swiss, then American, theoretical physicist who is among the founding fathers of “quantum mechanics.” He is famous for his “exclusion principle”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfgang_Pauli ↩︎

Wilhelm Heinrich Walter Baade (1893-1960) was a German astronomer who spent much of his life in the United States. He is famous for doubling the size of the universe in 1952 by discovering a second type of Cepheid variable stars. Various celestial objects are named after him. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Baade ↩︎

Enrico Fermi (1901—1954) was an Italian naturalized American physicist known for the development of the first nuclear reactor and his contributions to quantum physics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enrico_Fermi ↩︎

The Chandrasekhar limit is the maximum possible mass of a white dwarf star. If this limit is exceeded, the star will collapse to become a black hole or a neutron star (most of the time, in the latter star). Its value was calculated in 1930 by the Indian astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, when he was only 19 years old. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chandrasekhar_limit ↩︎

Igor Novikov (b. 1935) is a Russian theoretical astrophysicist and cosmologist, author of several very popular books. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igor_Dmitriyevich_Novikov ↩︎

Novikov, I. Black Holes and the Universe. (Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 54. ↩︎

Fritz Zwicky (1898-1974) was a Swiss astronomer and physicist of Bulgarian origin. He formulated pioneering ideas related to dark matter, and is considered the discoverer of neutron stars. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz_Zwicky ↩︎

Robert Andrews Millikan (1868-1953) was an American experimental physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923 for his work in determining the value of the charge of the electron and the photoelectric effect. He also investigated cosmic rays. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Andrews_Millikan ↩︎

William Samuel Sadler (1875-1969) was an American surgeon and psychoanalyst who formed a group of friends to publish The Urantia Book once they received these documents. From this group of friends came the Urantia Foundation, in charge of translating and disseminating the book. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Samuel_Sadler ↩︎

Phys. Reviews. Vol. 45 ↩︎

Thorne, K.S. (1994) Black holes and Time Warps: Einstein 's Outrageous Legacy (Picador, London) ↩︎

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (1904—1967) was an American Jewish theoretical physicist and professor of physics, famous as the “father of the atomic bomb” for his part in the Manhattan project, although he was later known even more for his opposition to the proliferation of nuclear weapons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Robert_Oppenheimer ↩︎

Lev Davídovich Landáu (1908—1969) was a Soviet physicist and mathematician, winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1962, a key figure in quantum mechanics and the physics of materials. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lev_Landau ↩︎

Albert Einstein (1879—1955) is the most outstanding of the scientists of the 20th century, famous thanks to his revolutionary theory of relativity. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein ↩︎

Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882—1944) was a well-known British astrophysicist in the first half of the 20th century. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Eddington ↩︎

Georgy Antonovich Gamov (1904—1969), was a Russian-born American physicist and astronomer, also known as George Gamow, who worked in almost all fields of astrophysics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Gamow ↩︎

Overbye, Dennis (1991) Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos. (HarperCollins) ↩︎ ↩︎

Clyde Lorrain Cowan Jr (1919—1974) and Frederick Reines (1918-1998) were the discoverers of the neutrino. Reines received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1995. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clyde_Cowan https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Reines ↩︎

Raymond “Ray” Davis Jr. (1914—2006) was an American chemist and physicist. He developed the first experiment capable of detecting neutrinos, which earned him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2002. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Davis_Jr. ↩︎

John Archibald Wheeler (1911—2008) was an American theoretical physicist who made important advances in particle physics. He is the one who came up with the astrophysical terms of black hole and wormhole. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Archibald_Wheeler ↩︎

Stirling Auchincloss Colgate (1925—2013) was an American physicist and emeritus professor of physics, heir to the Colgate toothpaste company. He worked on the first projects to create a hydrogen bomb, although he later abandoned it in favor of the study of supernovae. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stirling_Colgate ↩︎

Burbidge, E.M., G.R. Burbidge, W.A. Fowler, & F. Hoyle, Synthesis of the Elements in Stars, Reviews of Modern Physics (1957), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B2FH_paper ↩︎

Hoyle, F., and J. Narlikar. The Physics Astronomy Frontier. (W.H. Freeman & Co. San Francisco, 1980.) ↩︎

Fred Hoyle (1915—2001) was a British astronomer known for his stellar nucleosynthesis theory and his controversial views, especially his rejection of the Big Bang theory, which he named after himself. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fred_Hoyle ↩︎

Hong-Yee Chiu (b. 1932) is an American astrophysicist of Chinese origin who has worked for NASA. He coined the term quasar. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hong-Yee_Chiu ↩︎

Philip Morrison (1915—2005) was a professor of physics at MIT, known for his work on the Manhattan Project and his later work in quantum and nuclear physics, as well as cosmic rays. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Morrison ↩︎

Morrison, Philip, (1962) Scientific American 207 (2) 90. ↩︎

Asimov, Isaac, (1966) The Neutrino (Dobson Books Ltd., London) ↩︎

Neutral currents are one of the ways that subatomic particles can interact via the weak force. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutral_current ↩︎

Hans Albrecht Bethe (1906-2005) was a German-American physicist of Jewish origin, winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery in stellar nucleosynthesis. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Bethe ↩︎

Gerald Edward Brown (1926-2013) was an American theoretical physicist who worked on nuclear physics and astrophysics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_E._Brown ↩︎

The Maaherra case was a controversial 1991 copyright lawsuit brought by Urantia Foundation with a reader, Kristen Maaherra, who made an unauthorized publication of the book. ↩︎