[ p. 161 ]

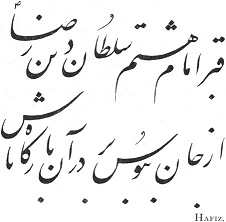

From thy soul, kiss the grave of the

Eighth Imam, Riza, the Sultan

Of the Religion; and remain

At the Gate of that Court.

Hafiz.

Many years had elapsed since the events narrated in the last two chapters. Among other things, the second Vakil-ul-Mulk, may Allah forgive him! had died, and a Governor-General, who was a stranger to Kerman, had been appointed.

During the previous winter a comet, which always portends calamity, had appeared. There [162] had been very little snow or rain, and in the spring the scanty crops were eaten up by locusts. The result was that wheat which, the year before, had been sold for four tomans a kharwar, now fetched eighteen tomans. In short, famine had fallen on the province.

Had the Vakil-ul-Mulk been alive, he would have sent a thousand camels to Sistan at his own expense to bring wheat to the city; but the new Governor-General only cut off the ears of the bakers when they sold their bread, made chiefly from millet, dear, and finally baked the chief baker alive in his own oven.

Allah knows that bakers in Persia are scamps, but this action produced no good result, as all the merchants who would have sent money to buy wheat from the other provinces were afraid that it would be seized by the mamurs, whom the Governor-General placed on every road, and who made matters worse, as they beat the camel-drivers and stopped the caravans until they received money; and so even dates and rice were not sent to Kerman, which was like a city besieged by enemies.

At last, however, His Excellency removed the mamurs, and then rice and dates reached the bazaar; but during that summer people mainly lived on fruit, which is a most unwholesome diet.

To add to our calamities cholera broke out [163] in the province. In the spring travellers had brought it from Baghdad to Tehran, whence it had reached holy Meshed. However, owing to the healthiness of Kerman and its distance from Meshed, it seemed probable that it would escape this calamity; but Allah, the Omnipotent, no doubt wished to punish us for our sins; and a returning pilgrim died of cholera at a village only one stage from Kerman.

This, too, need not have infected our beloved city, but his clothes were brought in and washed in a stream which passes through the gardens inhabited by the Gabrs.

It happened that there was a wedding that night at the house of Arbab Shahriar, the chief of the tribe; and before morning, the bridegroom, the bride, and seventeen of the guests were infected, all of whom died.

There is no place for pleasure between the Earth and the Heaven;

How can a grain escape from between two mill-stones?

When this calamity was known in the city, it became a Day of Judgment; and everybody fled who could. Now, although we Iranis are noted for our bravery in battle, I must confess that all of us, owing to our highly-strung nerves, which are the result of living in a very dry climate, fear the cholera, as if an attack of it were tantamount to the Angel of Death knocking at the door.

[ p. 164 ]

Even our noble Governor-General fled to a valley, where he posted his troops down below, to prevent any one from passing them; and he himself, with one servant, camped above near a tiny spring, and threatened to shoot any one who, on any pretence whatever, approached him.

The Vizier, too, was equally afraid; and, as he had heard that cholera never attacked people underground, he took refuge in a disused well and remained there for forty days. Since the Doctor Sahib, who laughed at us for being afraid without reason, and attended the sick throughout, informed me that by boiling all water and only eating cooked food, all cause of fear would be removed, I remained at Kerman with my family. Another reason for this was that my garden in the Bagh-i-Zirisf was watered by its own water channel.

However, many of my servants, acting against the Prophet’s tradition, which runs, “At the outbreak of an epidemic abide where ye are, as fleeing from a place is to escape from death to death,” fled to their homes and, later, I heard that all had died on the road, whereas, praise be to Allah, no one in my family, or indeed in the Bagh-i-Zirisf, was attacked.

After a month the cholera ceased in Kerman, but was raging in the adjoining villages; so the Governor-General, who had been sternly ordered [165] by the Shah to return to his post, and had been informed that he was considered to be the shepherd of the people, now gave orders that no one should enter Kerman without undergoing quarantine.

This, by Allah! was very astute, as the winter was setting in, and all the mullahs, Khans, and merchants gladly paid large sums of money to be allowed to return to their homes.

The English laughed at them; but, in truth, it is not that the English are braver than we Iranis. Allah forbid! I have read that their country is so wet and so foggy that their ideas come very slowly in consequence; and so they do not realise dangers as quickly as we Iranis. I represented this to the Doctor Sahib, who laughed immoderately, and said, “By Allah, that is the reason the French give for our defeating Napoleon!”

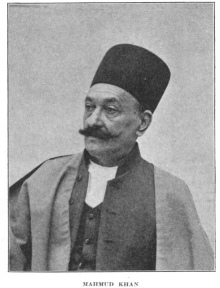

Now I had vowed a solemn vow that if the Imam, on Him be Peace! protected me and my family during this awful calamity, I would hasten to prostrate myself at his threshold. Consequently, when every one had returned and had congratulated me on my phenomenal courage, I explained the matter to them, and more especially to Mahmud Khan, who had occasionally stated that he too wished to participate in this grace.

Now I have not hitherto mentioned Mahmud [ p. 166 ] Khan, who was among the great people of Kerman, and who was a relation of my family. When a youth he had entered the college which Nasir-u-Din Shah, may Allah keep cool his Grave! had, at that time, recently opened in order to teach the young princes and Khans all European learning.

Mahmud Khan, however, so they say, was very stupid, and, after six months, the professors represented to the Shah that they had beaten him daily, imprisoned him, and indeed tried to teach him by every possible means, but in vain; and they had all sealed a declaration to the effect that he was incapable of receiving instruction.

The Shah, upon hearing this, reflected for a while and then said, “As thou art proved to be incapable of receiving instruction, it is better that thou returnest to thy home. Perhaps there thou wilt learn to distinguish between wheat and barley. Thou art dismissed.”

This happened many years ago; and as Mahmud Khan inherited twenty villages in the districts of Bardsir and Rafsinjan, and spent his whole time in looking after them, he became very rich.

Another thing aided this, namely, that he was miserly and would not have thrown a bone to the dog of the Seven Sleepers. Thanks be to Allah, we Iranis are, as a rule, very liberal, and we fully agree with Shaykh Sadi who wrote:

[ p. 167 ]

[ p. 168 ]

[ p. 169 ]

Generosity will be the harvest of life.

Freshen the heart of the world by generosity;

For ever be steadfast in generosity;

Since the Creator of the soul is beneficent.

But Mahmud Khan was so miserly that his horses were always hungry, so much so that one of them once attacked a man dressed in a green coat, thinking it was fodder! Also he kept the key of the storeroom himself, and every day gave out a very little butter and a very little rice for the daily food of himself and servants. Indeed, had he not been very stupid, no servant would have remained in his service.

Yet he was most fond of Europeans, and was the first Khan to be friendly to the Doctor Sahib. Indeed, he promised to give him land on which to build a hospital, and for three days he rode to his numerous gardens with the Sahib, and asked him to decide which one he considered to possess the most suitable air for the purpose.

However, he finally settled that he could not give any of his land, and so the matter remained, although occasionally His Excellency the Governor-General used to say in jest, “Well, Mahmud Khan, when is the hospital going to be built?” And he replied, “I beg to represent that I am busy with the matter.”

[ p. 170 ]

One day His Excellency informed the Khan that he wished to be his guest in his garden, and, although Mahmud Khan knew exactly what was right to do in such cases, he was too avaricious to incur the necessary expenditure. His Excellency was not pleased, and when in the afternoon he called together all the Khans, he turned the conversation on to the subject of avarice and miserliness, by saying that he had recently heard of a merchant of Isfahan, who was so mean that he ate his bread dry, and only took enough butter to cover the tip of a needle with the last mouthful. He added that he doubted whether any one could be more miserly than that.

Shaykh Ahmad, however, represented that he knew of a man who, every day, took a handkerchief to the grocer and bought a little flour, which he afterwards returned, complaining that it was mouldy. At the same time some flour stuck to the handkerchief, which he was careful not to shake; and, by doing this at several shops, he collected enough flour for a loaf of bread, and this he cooked himself with bits of bushes which dropped off the donkey-loads as they passed through the bazaars. For relish, he went about and sat down where he could smell the cooking of the kabobs in the coffee-houses. His Excellency agreed that [ p. 171 ] Shaykh Ahmad had given even a better example than his own.

Abu Turab Khan then represented that he had heard of a still worse case of a rich merchant of Yezd, who only allowed each member of his family a piece of dry bread to eat. One day his daughter, who was very beautiful, but whom no one would marry on account of the father’s evil reputation, took compassion on a poor old beggar and gave him her piece of bread.

Her mother, in the kindness of her heart, recommended that the girl should be given another piece, but the father, hearing what had happened, became like a madman, and not only cut off his daughter’s right hand, but turned her out of the house into the streets of the town.

The poor girl wandered about, not knowing where to go, when she was seen by the Governor-General, who was returning from a hunting expedition. Moved by her beauty and innocence, he took her to his women’s apartments and, seeing the nobility of her disposition, finally married her to his son.

On the wedding night the bride placed a bowl of sherbet before her husband with her left hand, and he, feeling shocked at this lack of good manners, quitted the room to complain to his mother. Meanwhile the girl prostrated herself on the ground, crying out, "O Allah!

[ p. 172 ]

why dost Thou suffer a creature to be humiliated for want of a hand which performed a good deed for Thy sake? Either restore my hand or strike me dead.”

The bridegroom, who had now for the first time heard from his mother of the noble act of the girl, returned, when the bowl of sherbet was again set before him by the bride, and this time with her right hand, which Allah the Omnipotent had restored. The youth was amazed, and prostrated himself to thank Allah for giving him as a wife a maiden who had received such a signal favour from heaven.

The next day the miserly merchant was summoned, and, as he could offer no excuse for his barbarous conduct, he was sentenced to have both his hands cut off and to be killed by having food rammed down his throat. His daughter, however, interceded for him and he was pardoned, and it is stated that he repented, and, proceeding on a pilgrimage, died on the way.

After this His Excellency said nothing, and when he rose up to leave, it was evident that he was displeased with his host to whom he showed no kindness. The result was bad for Mahmud Khan, as, after His Excellency had finished his repast, his servants broke all the dishes, including four china sherbet bowls [173] which had been in the Khan’s family for many generations. As Naushirwan the Just truly said:

The slave who is bought and sold is freer than the miser:

For the slave may one day be free, but the miser never.

Mahmud Khan was of a very powerful build and wore long moustaches, which, when he twisted them, made him look very fierce; and indeed he was noted for his bravery, as, on one occasion, he rode alone after a band of seven Afshar robbers and killed three of them.

Another story, too, he used to tell, which was that, one evening, he was in the mountains and just finishing his prayers, when a leopard attacked him, but with one blow from his sword he cut off its head, which he nailed up over his gate, just as lovers of sport fasten the skulls and horns of wild sheep.

The Khan informed me that he had decided to take Ali Khan, his son-in-law, with him. Now this youth, unlike his father-in-law, was very small and slight, so that he was sometimes compared to a sparrow. He was one of the Khans of Bam, and his ancestor rendered a great service to the Kajar dynasty by seizing Lutf Ali Khan, Zand. This proud warrior held Kerman for many months against the might of Aga Mohamed Shah, whose entrenchments are still standing; but, seeing that there [174] was no hope except in flight, he escaped from the city and fled to Bam, where he was seized and thrown into chains.

Ali Khan, on this account, and also because he owned much property in Narmashir, where the best henna in the world grows, was very proud and quick-tempered, but yet the Khans of Kerman, if not as rich as those of Bam, always consider themselves nobler and higher, and it was deemed a great honour for Ali Khan to become the son-in-law of Mahmud Khan.

When this important question had been decided, we had many meetings and discussions as to what date we should start on, and what route would be the best to follow. We soon agreed that a few days after the festival of No Ruz would be a suitable date, but it was very difficult to fix on the route.

The direct track lies across the Great Desert for half the distance, and Mahmud Khan said that he wished to travel that way because he hoped one day to construct a road by which pilgrims could drive to the Sacred City. At this, Ali Khan, who was, in truth, a light youth, laughed behind Mahmud Khan’s back, and whispered that he was not likely to have leisure from building the hospital to devote to constructing a road.

[ p. 175 ]

We finally persuaded Mahmud Khan to travel by Yezd, as to that important city the road is good, and the desert is only fifty farsakhs wide at this point. Moreover, I represented to him that by travelling this way he would be able to visit his villages in Rafsinjan; but what made him finally agree was that I said forage and food were much cheaper by the Yezd route, and that in Rafsinjan he would obtain everything free of cost.

Thus he agreed, and for the next four months we were busy making all the necessary arrangements, buying mules and horses, and also the necessary outfit. The most difficult point was to settle which servants to take and which to leave behind, as they represented that it would be an act of merit on my part to arrange for them all to go.

However, that too was ultimately arranged by Rustam Beg stating that he had already been twice to Meshed, and that he would not feel happy if any one but himself was left in charge of the house and property, but that he did not require any other personal servant to stay behind with him.

It remains to refer to the religious exercises to which we delivered ourselves before starting on this solemn pilgrimage. Each of us, in turn, held a meeting at which the calamities experienced [176] by Ali, Husein, and the other holy Imams were recited.

The black-hearted people who slew the offspring of the Prophet with malice;

They claim to belong to the religion but murder the Lord of the Religion;

They commit to memory the Koran and draw the sword, reciting the chapter Taha;

They wear the Yasin chapter as an amulet; but murder the acknowledged Imam.

Afterwards, we entertained our relatives and friends at luncheon and received gifts for the road, such as tea cups, tea, and other such useful presents.

In short, owing to the arrangements which had to be made and these meetings, the winter passed very quickly, after which there was very little leisure left before the actual day of starting.