[ p. 177 ]

I was afraid of the Prison of Alexander;

And fled to the Country of Solomon. [1]

Hafiz.

Again the joyous festival of No Ruz came round, and when its thirteen days were passed it was high time to beat the drum of departure. At last the Chief Astrologer pronounced a certain Thursday to be a propitious date, and that evening, accompanied by hundreds of relatives and friends, we started for a garden which is situated about a farsakh from beautiful Kerman. It may be thought that this was a very short stage for travellers who had such a long journey before them; but the fact is that we Persians have more experience of travelling than any other nation, and so we understand that on such occasions much is invariably left behind. In [178] truth, upon reaching the garden every servant found that he had forgotten something; and, but for this custom of ours, termed “Change of Place,” our position would have been difficult.

I have not mentioned that, as soon as it was known that some of the leading inhabitants of Kerman were about to undertake the pilgrimage, at least fifty of our fellow-citizens decided to accompany us; and as it is a pious deed to facilitate pilgrimages, we agreed to allow them our protection on the road.

The following day we marched a full stage, and the third day brought us to Kakh, the chief village of the district of Khinaman; it is a very ancient village, so much so that I have read that it supplied to the armies of the Sasanian monarchs seven intrepid warriors mounted on bulls. Its Governor besought us to halt a day; but Mahmud Khan refused, and, on the fourth day after starting on this journey of grace, we entered the district of Rafsinjan, which is renowned for its pistachio nuts and almonds. Indeed, so delicate are the shells of the latter that they are known as “paper.”

Mahmud Khan insisted on our halting for two days while he visited his villages, and, as the Governor of Rafsinjan was a well-known Khan of Kerman, it was very agreeable to stay there in his service, and to give him the latest [179] news of His Excellency the Governor-General and of Kerman.

Husein Ali Khan had ruled Rafsinjan for over twenty years, in fact ever since he had rendered a signal service to the Shah by killing a rebel Buchakchi chief. This wild bandit for a long time refused to visit the Khan and make his submission; but, at last, the latter sent him a Koran sealed with his seal, and the promise that, so long as he was on the earth, no harm should happen to him. The Buchakchi, upon seeing the Koran and hearing the promise, finally came into Rafsinjan; but the Khan, who was very astute, sat in a specially prepared pit underground, and, being thus freed from his oath, shot the bandit who had killed hundreds of travellers. To reward him for this great service the title of “Amir of Amirs” was bestowed upon the Khan, who, a few years later, again showed immense capacity in the art of government.

It happened that one of the Hindus, of whom there are several at Kerman, was robbed and murdered in the Rafsinjan district; and the English Consul Sahib sent repeated telegrams to the English Legation, with the result that every day fresh orders came from the Minister of the Interior for the murderers of this Hindu to be caught and punished; there was also a threat of dismissal unless this was done quickly.

[ p. 180 ]

Now all the while the Governor knew who the robbers were, but he did not wish to show great severity, as, after all, the killing of a Hindu was not a great crime. However, he was obliged. to seize the men and informed the Consul Sahib of the fact, and that he was ready to have them executed. But that official, who had been hard throughout, to his surprise refused to have the men executed without proofs of their guilt.

The “Amir of Amirs” pondered for a while, and then asked the interpreter of the Consulate to go into an adjoining room and expect the proof desired by the Sahib. The prisoners were now brought in, and all the, farrashes were dismissed.

The Khan then spoke most affectionately to them and said, “O my brethren, we are all Mussulmans, and I, like you, rejoice at the death of this infidel, may his soul remain in Hell! I have dismissed all my servants that I might secretly congratulate you; and I wish to know to whom the most credit in this meritorious deed is due.” Hearing this, Iskandar Khan replied: “Praise be to the Allah, we were all partners in this pious deed. Ibrahim Khan seized the Hindu, Abdulla Khan held his donkey, and I shot the infidel, and Allah knows he bled like a pig.”

[ p. 181 ]

No sooner had he finished than the Governor called out “Bacha!” [2] and, when his farrashes returned, he asked the interpreter if he was at last satisfied of the guilt of the prisoners, and, upon his replying in the affirmative, he ordered the executioner to take them to the Great Square and execute them. That dread official afterwards mentioned that the men were as if in a dream, and never seemed to realise what was happening, so simple were they that they could not understand the astuteness of a high Persian official.

Upon leaving Rafsinjan we rode to visit the famous “Well of the World.” It is a mighty chasm in the desert, and a great river flows beneath it. They say that every year many camels, sheep, and goats tumble into it and are carried away, so great is its force. One day this water, if Allah wishes, will be used for cultivating the waste land of Rafsinjan, and indeed it resembles an untouched gold mine.

The next place of importance on our journey was Anar, which contains a shrine dedicated to Mohamed Salih bin Musa Kazim. In it is a Koran stand, made of sandal wood, in which ivory is inlaid, and it is so beautifully carved that the work of to-day is nothing in comparison.

[ p. 182 ]

The Governor at the time was Murtaza Kuli Khan, Afshar, who was appointed to this, a frontier district of the province, as the Lashanis and other Fars tribes all feared him because of his cruelty. It is related that once, when riding [183] near Anar, he saw a child tumble into a mill-race. One of his servants galloped forward to save it, but he shouted out, “Stop and let us see what will happen.” Thus, by his lack of humanity, he deprived a poor widow of her only son whom she relied on to provide bread for her old age, when he grew up.

(Dated A.D. 1359)

The day before our arrival he had committed a still more terrible deed. One of the leading landowners had some months before complained of his tyrannical behaviour, and the Governor-General had rebuked him for oppressing the people he ruled. Upon receiving this message from Kerman, he had summoned the landowner and addressed him as follows: “Thou art the first man who has been brave enough to complain of me to the Governor-General, and thy heart must be different from other men’s hearts.” He then roared out to the Chief Executioner, “Take out his heart and let me see it.” The bloody order was instantly carried out, yet even this did not sate his fury for vengeance, for he also refused to allow the corpse to be buried.

As a result of this terrible outrage the whole population of Anar had taken sanctuary at the Telegraph Office, the wires of which terminate at the “Foot of the Throne.”

At first the telegraphchi, who received fifty tomans every month as a gift from the Governor, [184] refused to send their petitions either to Tehran or to Kerman, so the villagers threatened him and his family with instant death. Upon this he complied, and he explained afterwards that he really intended to help them all the time, as he was horrified at the crime; but he feared that, unless he could plead that his life was threatened, the savage Governor might kill him too.

Glory be to Allah! no sooner was the state of affairs explained than most severe orders came for Murtaza Kuli Khan to proceed by post to Kerman, where he met with the punishment he deserved. By Allah! I think that he was really mad.

Three stages of desert with salt water had now to be traversed, and Mahmud Khan narrated to us that this desert was haunted by vampires, who attack men overcome by sleep, and drain their life-blood by licking the soles of their feet. He added that, some years ago, two muleteers whom he knew lost their way in a storm in this very desert, and finally, being utterly tired out, were obliged to go to sleep until the morning. They were much afraid of the vampire; but, being clever Kermanis, they decided to lie down feet to feet and so fell asleep. Shortly afterwards the dreaded vampire came upon them, and began to prowl round them to discover their feet; but at each end it found a head.

[ p. 185 ]

In despair it fled, exclaiming:

I have wandered through one thousand

Six hundred and sixty-six valleys,

But nowhere have I seen a two-headed man.

With such stories did we pass the time on these three stages, in which the water is so salt that to drink it causes nausea; but yet it is impossible for the sons of Adam to exist without water, and so we consoled ourselves by feeling that the greater our privations the greater the merit of our pilgrimage; and I quoted:

Consider hardship as ease if the matter be important.

Upon hearing this every one became happy, and the desert stages were quickly passed.

Throughout the journey Ali Khan was always trying to shoot partridges; but he was not a good shot; and when, at last, he brought one into the stage, and with much pride presented it to Mahmud Khan, the latter exclaimed, “Of course it was sick.”

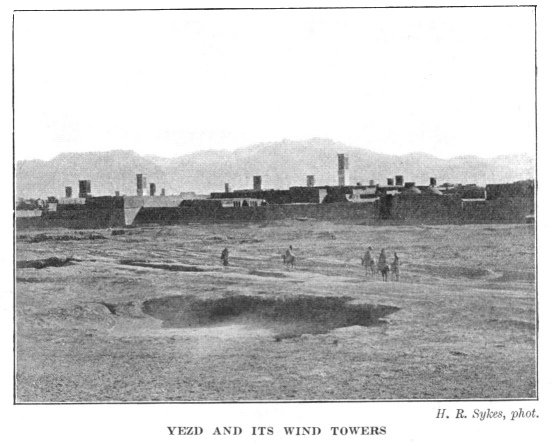

At last we reached the province of Yezd, and that night we halted but a short stage from one of the famous cities of Iran.

Yezd was the first city of our mighty empire other than Kerman which I had visited, and, by Allah, well does it merit its reputation of having served as a prison house in which Iskandar imprisoned his enemies, the refractory Divs. [ p. 186 ] Indeed, when approaching it, I was assured that the city was quite close; this, however, I could not believe, as all I saw was a hideous desert of sandhills, a fit abode for Ghouls and Afrits, but nothing else.

Even as this thought came into my mind a dreadful wind began to blow, and everything was black as night. However, we rode on like brave Persians and dimly saw two high towers, which, had I not been possessed of much wisdom, I should infallibly have mistaken for a castle built by the Divs. At last some mean mud garden walls appeared, and riding between them, we had entered Yezd.

H. R. Sykes, phot.

[ p. 187 ]

Yezd is indeed an unfortunate town, as, after having served as a prison to Iskandar, it was founded as a city by Yezdigird, whose evil title was “the Sinner.” Indeed so wicked was he that Allah the Omnipotent did not permit him to die an ordinary death; but, when he visited the sacred lake of Su, in the mountains of Nishapur, a white horse suddenly appeared out of the lake, kicked the monarch so that he died, and then as suddenly disappeared in the waters of the lake.

To come down to later times, too, my father, may Allah forgive him! I well remember used to mention how that when Fath Ali Shah was the Sign of the power of Allah, and Yezd had the honour of being ruled by Mohamed Ali Mirza, one of his sons, a certain Abdur Razzak Khan, not only rebelled, but insulted and outraged the Prince’s family. However, Abbas Mirza, the Rustam of his age, seized the criminal, who was handed over to Mohamed Ali Mirza. He, a true drinker of blood, with one stroke of his victorious sword smote off the accursed rebel’s head.

The Yezdis are so cowardly that nowadays no soldiers are drawn from the population, and, indeed, what can be expected of a people which lives in a country of sandhills, where even the milk cannot be drunk, as it both tastes and smells so strongly of cotton seed, on which alone [188] the cows are kept alive? It was a regiment of Yezdis who, after returning from the conquest of India, asked the great Nadir to give them an escort to see them to their home. But yet, although entirely lacking in manliness, the Yezdis are good weavers, and some of the silk they manufacture is esteemed highly in Persia, although, of course, it is not as famous as the shawls of Kerman.

Sad to say it was a Yezdi who introduced smoking opium among us, and, alas for Iran! why has this calamity befallen us? Allah knows but I would blow from a gun those who introduced this accursed habit.

First of all, the opium is smoked with charcoal; then the miserable man ever craves for something stronger, until he smokes opium once burnt, and thereby concentrated, in an old, much used pipe which is heated over a lamp.

The Doctor Sahib told me that whenever a mullah attacked him for holding the religion of Hazrat Isa, on Him be Peace! he invariably replied that rather than that there should be divisions among the “Possessors of a revealed book,” it was better for the entire strength of both religions to be exerted to stop this calamity. And by Allah this is true, as Hafiz says:

If grief should array its army to shed the lover’s blood,

I and the Saki will unite to destroy grief.

[ p. 189 ]

The ruler of Yezd was one of the princes of the Royal family who, when I was honoured by appearing in his presence, showed me particular notice, and said, “Thou art well known to me, Nurullah Khan, by thy poems. Inshallah! while thou remainest at Yezd thou art my guest.”

In truth, not only was I treated with great distinction, but before we left the Master of Horse of His Highness brought me a beautiful Arab horse with its tail dyed scarlet, thereby showing that it came from the royal stables. In return, I wrote a panegyric on the horse and His Highness, who, I afterwards heard, said that his name would, on this account, never be forgotten in Iran. It ran as follows:

Bravo the Charger with hoofs like Shabdiz and a head like Rakhsh, [3]

Awaji [^55] on the dam’s side, whose sire was Yahmum. [^55]

Sometimes he is like a bird in gliding and a snake in twisting;

Sometimes he dances like a pheasant and bounds like a ball.

An alligator in the sea and a leopard on the mountain.

A crane in the air and a peacock in the street.

He gallops without urging or inciting.

Fiery as the angel of fire: and in water like a duck.

His muscles are tight like a bow-string, his sinews like armour, and his mouth well-shaped,

His head a date palm, his tail a cord, his flanks of stone and his hoofs sharp-edged.

A late sleeper but an early riser, fleet and far-seeing: [p. 190 ]

Easy to handle, a good goer: well-behaved and well-bred,

Hard-footed, tough-thighed, straight-legged and round-hoofed.

Sharp-eared, flat-backed, smooth-skinned and short-haired.

Fleet as the clouds, swift as the wind: in thunder like lightning and also in his stride.

Destroyer of mountains, Splitter of storms, Scaler of cliffs and Discoverer of roads.

With legs of a wild ass, liver of a lion, pace of a leopard and the determination of a racer:

Throat of an elephant, breast of a rhinoceros: the jump of an ibex and the disposition of a wolf.

Sharp-eyed, iron-livered, steel-hearted and hard-lipped:

With teeth of silver, nostril like a well, throat like a tube, and a brow like a tablet.

Spear, sword, lasso, battle-axe, arrow and bow

Are his neck, ear, tail, hoof, mouth and leg.

The Governor has given me such a horse without a saddle,

Such a horse is like a jar without a handle.

That night the Master of Horse again came with a message from His Highness to the effect that he had originally given orders for one of his own saddles with gold trappings to be sent with the horse, and that he hoped the negligence of his servants would be forgiven. He asked me to inspect the holsters, in which I found a pair of gold-mounted pistols, and, overwhelmed at the munificence of the noble Kajar prince, I exclaimed, “By Allah! Hatim Tai has returned to life.”