[ p. 138 ]

Yet Ah, that Spring should vanish with the Rose!

That Youth’s sweet-scented manuscript should close!

The Nightingale that in the branches sang,

Ah whence, and whither flown again, who knows!

Omar Khayyam.

It is one of the chief glories of Iran, that it has been ruled by monarchs who have become renowned throughout the Seven Climates. Perhaps the greatest among our many famous rulers was Jamshid, who introduced the use of iron, the art of weaving, the art of healing, and indeed many other arts, on which the happiness not only of Persia but of the entire world is based.

Among his inventions was that of wine, which was discovered in the following manner:—The King, who was immoderately fond of grapes, stored a quantity which fermented. Seeing this, he placed them in jars and had the word “poison” written on them. It happened that [139] one of his wives, who was suffering from a torturing ailment, decided to commit suicide, and so drank of the contents of the jars, which immediately cured her. Jamshid and his courtiers thenceforward became addicted to the use of wine, which has, since that date, been known as “Sweet Poison.”

By the orders of the Koran the drinking of wine is forbidden; but yet the habit has always been so strong among Persians that many of them still drink it, but always in private, and, generally, having the desire to give up the bad practice; also they repent when they yield to this weakness, and pray to Allah to grant them grace. By thus repenting, their prayers are perhaps accepted, for sincere repentance wins the favour of Heaven.

In truth, many Mussulmans would not approve of Hafiz when he writes:

Saki, come! my bowl rekindle with the light of lustrous wine;

but they understand that the poet means by the Saki or Cupbearer the Spiritual Instructor, who hands a cup of celestial love, which is typified by wine.

However, in discussing this important question, Jamshid has been forgotten. He, apart from the wonderful discoveries made by him, was able, by means of his seven-ringed cup, not only to [140] predict the future, but also to survey the entire world. In short, Jamshid ranks with Suliman or Solomon, son of David, as the lord of the Divs; and to-day there is the Takht-i-Suliman and also the Takht-i-Jamshid close together in Fars; and they say that there is no doubt whatever that the latter is much finer than the former.

Major J. W. Watson, phot.

Among the benefits conferred on the people of Iran by this mighty monarch, I will now refer to the institution of No Ruz or New Year’s Day, which, by his decree, was fixed at the Vernal Equinox.

I marvel when I read that, in Farangistan, the year begins in the “Forty days of Cold.” Praise be to Allah, Jamshid decreed our New Year, both in accordance with nature and science.

[ p. 141 ]

With us the “Forty days of Cold” commence on the shortest day of the year, as is meet and befitting; and are succeeded by the “Small Forty Days,” which are only, in reality, twenty days.

Now, seven days before the end of the great cold period we say that the earth breathes secretly, and that, twelve days later, it breathes openly.

When the “Small Forty Days” are ended there are two periods of ten days, known as Ahman and Bahman, as the old verse runs:

Ahman has passed and Bahman has passed,

With whom should I please my heart?

I will take up a half-burnt piece of wood

And kindle flames throughout the world.

This signifies that now there is no more fear of cold, albeit ten days before the festival is the “Season of the Old Woman,” which, as its name implies, is sometimes very unpleasant and disagreeable.

Meanwhile, however, the desert is becoming green and the blossom has begun to appear on the trees, and, as Omar Khayyam sings:

Irani indeed is gone with all his Rose,

And Jamshid’s Sev’n-ring’d Cup where no one knows;

But still a Ruby kindles in the Vine,

And many a Garden by the Water blows.

And David’s lips are lockt; but in divine

High-piping Pehlevi, with “Wine! Wine! Wine!

Red Wine!”—the Nightingale cries to the Rose

That sallow cheek of hers to incarnadine.

[ p. 142 ]

Come, fill the Cup, and in the fire of Spring

Your Winter-garment of Repentance fling:

The Bird of Time has but a little way

To flutter—and the Bird is on the Wing.

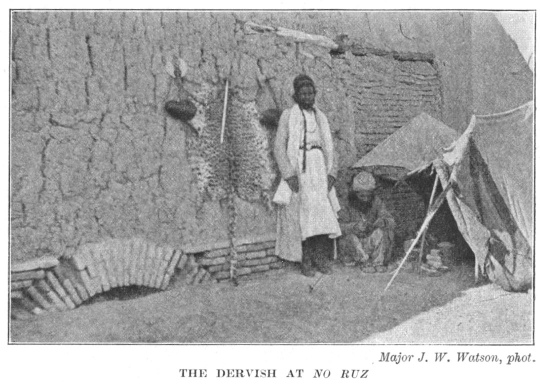

At this period, just before the “Season of the Old Woman,” dervishes pitch tents outside the houses of the great and recite prayers for their prosperity. It is customary to make them a handsome gift; but if this be not done quickly, they blow their horns at intervals during the night and, by rendering sleep impossible, loosen the purse-strings of the rich Khan or merchant. Indeed I have never forgotten the awe with which I regarded a dervish at Mahun, who possessed a beautifully inlaid axe of a great age, a begging bowl, on which the combat of Rustam with the White Div was carved, and a very fine lion’s skin. While I was gazing in wonder at these articles, Ya Hu was pronounced like a lion’s roar and my heart became like water. Ever since that date I have reverenced dervishes, as is but right and befitting.

I now come to the preparations for this our greatest festival. Some ten days before it, “House Shaking” is performed, every room being carefully swept and the carpets taken out and beaten. New clothes, too, are made for every member of the household. Already some wheat has been prepared by being wetted so that [143] it sprouts by the great day. Special cakes of fine wheat-flour, with butter and sugar, are also baked; and the innumerable varieties of sweetmeats for which Yezd is especially famous: dried fruits and nuts are also provided.

On the last Wednesday before the fête, just before sunset, three fires of bushes are lighted in the courtyard, and every member of the household jumps over them, reciting “Paleness yours and redness ours,” signifying thereby that all ill-health is left behind and ruddy cheeks will alone be seen in the future. Rue and mastich are mixed and held in the hands while jumping over the fires, and are thrown on them to avert misfortune.

At night pilao, in which slices of paste are mixed, is eaten; and an earthenware jar of water, in which some copper coins have been thrown, is hurled into the street from the housetop.

It is considered to be auspicious to keep all doors open; and it is the custom to take a good or bad omen from any conversation that may be overheard, the listeners standing on a key, the symbol of opening, and listening with bated breath.

If they hear such conversation as “Your place was empty. We spent a happy night,” they creep away highly pleased; but, on the other hand, if they hear Allah forgive the [144] deceased, he was a good companion,“ or ”His disease has become so serious that neither medicine nor prayer has any effect," they feel that the New Year will be inauspicious.

Girls, too, who hope for marriage, are taken by a woman mullah to a place where four roads meet. There they sit with a lock fastened on to their dress and offer sweetmeats to passers-by. This is termed “Luck Opening,” as every one who partakes of the sweetmeats first turns the key in the lock and thereby opens the way to good fortune for the damsel.

The night before the fête gifts of money are sewn up in small bags or wrapped in paper and presented on the fête day to each member of the family, and the poor are not forgotten. The bath is then visited and, after careful dyeing of the hair, the new clothes are donned. On this occasion every one cuts his nails and throws the parings into running water, thereby losing all bad luck.

Upon returning home, two hours before the equinox, a white cloth is spread with seven articles, all of which commence with the letter “S,” such as sirka or vinegar, sib or apple, etc. etc. All fruits, and more especially melons, which have been carefully preserved throughout the winter, are also set on the table, with sweetmeats and dried fruits.

[ p. 145 ]

Eggs dyed red are also baked and eaten by all, the mother eating one for each of her offspring. Candles, to the number of the children in the house, are lighted, and, above all, a live fish is placed in a bowl which, when the new year begins, instinctively turns towards Mecca.

Milk is kept boiling as a sign of abundance, a prayer carpet is spread, and the following prayer is repeated three hundred and sixty-six times:

O the Turner of the hearts and eyes!

O the Lord of night and day!

O the Changer of conditions and dispositions,

Turn Thou our condition and better it.

Gold coins and wheat are now held in the palm of the hand, as also the woodlouse, an insect which brings good luck; and as the New Year commences, the sweetmeats and fruit are distributed, and every one gazes at the woodlouse for choice; or, if not, at a narcissus, at water, or at red clothes.

The gate of the house is shut an hour before the equinox, and no one is allowed to enter from outside; but, as soon as the new year commences, the master of the house goes out into the street with some sweetmeats, and after having distributed them and walked about, he re-enters his house.

Visiting and feasting are then the order of the [146] day; and every woman who enters a house from outside must do so with her veil half-lifted, so that her eyes and eyebrows are visible; only women who have come to wash a dead body enter closely veiled.

People known to be unlucky, or those who bring ill luck to others, such as executioners or members of their families, are rigidly excluded on this day. In this connection there is the story told of Shah Abbas who, when starting on a hunting expedition which proved to be a failure, first looked at an ugly old man.

Upon his return he sent for him, intending to kill him. The man asked why he should be doomed to die; and the Shah said, “Because thy ill-omened visage has spoilt my hunting.” The intended victim retorted, “May I be thy Sacrifice! but thy visage will be still more ill-omened if it brings death with it.” Upon hearing this, Shah Abbas laughed and dismissed the man with a gift.

For twelve days no work is done, nor can any enterprise or journey be undertaken. On the thirteenth day the house is unswept, and every one goes outside and sits in the green wheat. If the house be not left absolutely empty, misfortune will take up its abode there.

Before the day has set, it is most auspicious for ladies to pound up three peas’ weight of [147] pearls with sugar and swallow the mixture; and every one who can afford it performs this rite. Alhamdulillah! pearls are abundant in Persia, as they are found mainly in the Sea of Fars.

I think that, in this brief account of No Ruz, I have explained how every one, whether rich or poor, rejoices that the winter has passed, and that the time of flowers, of the glory of the gardens, and of the sweet song of the bulbul is approaching. As the poet Kaani wrote most beautifully:

It is the New Year’s Day. O Saki, hand the cup round;

Do not heed the turn of the wheel and the revolution of the heavens.

O Turk, the sin [1] of the cup is enough for me on the New Year’s day:

I do not care for the seven sin, as the dregs of wine suffice for me.

The people are talking of new clothes;

But I am longing for a cup of wine filled to the brim.

Every one places sweetmeats on his tablecloth and utters prayers;

But I wish for abuse from thy sweet ruby lips.

Every one holds silver and grains of wheat in his hands;

But I prefer the grain of the mole on thy silvery face.

Pistachios and almonds are the relish of the festival for others:

But, with thy lips and eyes, I do not want pistachios and almonds.

Men burn Ud [2] on New Year’s day, and I am lamenting like an Ud [p. 148 ]

For one who, with her black mole, will spoil Islam.

People kiss each other and I am dying of grief;

Why should another kiss that sweet-lipped one?

Vinegar is placed on the tablecloth by every one;

And my beloved wrinkles her rosy face into vinegar with anger.

At this season, too, it is customary to play games; and, in every open space, both men and boys play leap-frog, rounders, tip-cat, and other games, while, outside the city, the sons of our Khans throw the javelin at full gallop, and then catch it as it rebounds from the ground.

They also practise galloping past an egg placed on a little mound of earth; and so perfect is the marksmanship of our best sowars that, with a single shot, they break this egg; and it always makes me proud to think that the hearts of our enemies would be bigger than eggs, and that none of them could escape from the unerring bullets of the sowars of the victorious Shah.

Now we also practise marksmanship on foot; and one of the high officials of His Excellency used to throw up copper coins into the air, which were almost always hit by our Governor-General with his rifle. This official used to ask us courtiers to give two kran pieces for His Excellency to shoot at; but we only saw copper coins used, and when we remonstrated, this astute individual always replied that it was his perquisite, and after all, he underwent much [149] trouble in this business, as if the Governor-General were unsuccessful he always abused the official for throwing up the coins in a stupid fashion; also, once or twice, the bullet passed just over his head; and so there was danger in what he did.

But, in my opinion, nothing that is done in the way of exercises at No Ruz is so important as the science of wrestling, in which we Kermanis surpass all Persians, just as Persians excel all other nations. Now I propose to give you some details about wrestling.

The patron saint of pahlawans or wrestlers is Puriavali, who was a famous champion. He was, on one occasion, travelling to the capital to wrestle with the chief wrestler of the Shah, when, near the City Gate, he saw an old woman distributing sweetmeats. Inquiring the reason of this charity, the old woman replied that she was doing this to invoke the aid of the Imams to give her son, who was to wrestle with Puriavali on the morrow, victory over the latter, as she depended on him for her daily bread.

On hearing this, Puriavali was so moved that he made a vow that he would constrain himself to be beaten by the son. Indeed, his inward eyes were opened, and he, at that instant, miraculously attained sanctity.

On the morrow, when he closed with his rival, [150] he allowed himself to be thrown on his back in the first bout, to the great surprise of the spectators and to the intense indignation of his forty followers. When the contest was over, he informed the latter that they should leave him and go their ways, as his soul had attained a state of rest which he could not obtain by mere brute force; and, from that day until he died, he led the life of a saint.

The “House of Force” is a room with sitting places all round lighted by skylights. In the middle a six-sided pit is dug about seven feet deep. Dry bushes are brought and packed closely together, with their roots in the ground. A mat is spread over them, and soft earth or horse litter is heaped on to a height of a foot and a half. The surface is then trampled upon until it becomes soft and smooth.

To the west of the pit the Murshid’s raised dais is set next to the entrance to the arena, which is purposely built so that persons entering it should be obliged to bend very low as a sign of humility.

The Murshid sits on the dais and a bell attached to a chain hangs over his head. A feather is fastened to the bell in memory of any champion who learned his profession and attained fame in the school, just as Nadir Shah wore four feathers in his crown to show that he was [151] monarch of Persia, India, Afghanistan, and Bokhara. A drum and a samovar are also placed on the dais.

The Murshid is generally a dervish, who has devoted himself to the theoretical and spiritual side of wrestling, although sometimes he is a retired champion. He plays on the drum and recites verses while the pahlawans are exercising or wrestling, and at the end of the performance he distributes hot water and sugar.

When a wrestler is about to enter the arena he kisses the threshold and salutes the Murshid, “Peace be on thee, O Murshid.” The latter replies “Peace be on thee, O pahlawan, Thou bringest blessing.” The Murshid also swings the bell when the chief wrestler enters the arena. The pahlawan kisses the edge of the Murshid’s dais and passes into the arena. He then puts on the wrestler’s drawers, which he first kisses. They are made of stout cloth, and descend to below the knees, with leather knee-caps and a leather thong round the waist.

The first exercise generally consists in passing the arms through two slabs of stone, each weighing about 90 lbs.; and, lying on the back, each slab is alternately raised by rolling the body to one side and then to the other. This is to strengthen the shoulders.

Another exercise consists in “swimming” on [152] a board, during which the Murshid recites the poem beginning with:

The Emperor of China had a daughter like a moon;

But who has seen a moon with two raven tresses?

After that clubs are brought in and the Murshid recites:

The rose trees are in bud and the nightingales are intoxicated;

The world has attained its majority; and lovers sit down to a feast.

To conclude these preliminary exercises, each pahlawan in turns whirls round the pit.

I hope that by the above description I have explained how very perfect and complete are the exercises for wrestling in Persia; and I now ask you to accompany me to, see the match which had been the theme of conversation in Kerman since the autumn, for it then became known that the chief wrestler of the Shah, Isfandiar Beg, who was a Kermani, had, upon visiting his home, been challenged by the chief of the Kerman pahlawans, Abdulla Beg, who had never been defeated.

Three days before the match took place, a notice was posted up that there would be “Strewing of Roses”; and, in honour of the announcement, all the coffee houses and shops in the vicinity were gaily decorated, as indeed was the wrestling school, the pillars of which were draped with valuable Kerman shawls. Flowers, too, were profusely displayed; but, on the Murshid’s dais, there was only the battle-axe, the horn and the begging bowl of the dervish, arranged on a lion’s skin. Two peacocks’ feathers, one in honour of each champion, were suspended over the bell.

[ p. 153 ]

[ p. 154 ]

[ p. 155 ]

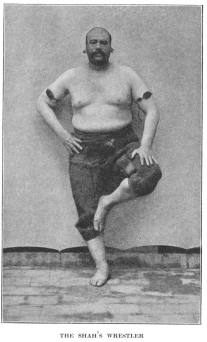

On the day of the match the “House of Force” was filled from early dawn; but it was not until two hours before sunset that His Excellency the Governor-General arrived and the Murshid asked permission to begin the contest. This being granted the two wrestlers were introduced; and, by Allah, perhaps they were the two strongest men in the world.

The Shah’s wrestler, who was several years the older, appeared to be like a massive tower, in fact if anything too heavy. He had, however, the reputation of being very alert and quick of eye, and full of tricks. Indeed he was known by the sobriquet of “Tricky.”

Abdulla Beg, on the other hand, was as perfect as a picture and well proportioned. His head round and of medium size, his ears small, his eyes big, his nose straight, his face dry and fleshless, his neck long and thick, his chest broad and deep, showing his capacity to hold his breath. His arms were long, and, in the upper part, were three muscles termed “little [156] fish”; his forearms full, his wrists hard and fleshless, his fingers drawn and straight, his waist small, his thighs full, the calves of his legs muscular and showing great development, and his feet arched. Indeed, he was so perfect a man that every one burst into acclamations of surprise and praise.

The respected head of the quarter, who was a Sayyid, and himself an old wrestler, first addressed the champions, and warned them not to bear malice against one another; he then joined their hands and the wrestling began, after the permission of the Murshid had been received, and the latter then recited:

Puriavali said that the quarry is in my lasso,

And that by the help of David my fortune is high.

If however thou thirstest for grace, learn humility,

Because land which is high can never receive water. [3]

Then he broke into reciting the “Flower of Wrestling,” beginning,

In valour and bravery thou art the bravest in the world:

In the presence of thy cypress-like body, the cypress itself has no worth.

The moment the hands of these two pahlawans had touched one another, they sprang in opposite directions, each taking up a position. Abdulla Beg, full of pride, would stand erect whilst his opponent was bending his body and was looking [157] exactly like a fighting cock. Then they began to move round and round, always on the look-out to secure an advantage over the other. Now they closed and again they separated. Then they put one hand on the back of the neck of the other.

The Shah’s pahlawan at this point being more alert than Abdulla Beg, bent down and, dodging his head under Abdulla Beg’s left arm, was, in the twinkling of an eye, behind his back; but the latter finally shook him off. Both men received applause for the skill and strength shown in this bout.

Again they closed and again they separated. The fourth time, Abdulla Beg got behind his opponent, and seizing the leather belt, tried to roll him on his back. The Shah’s wrestler, in turning suddenly, thrust his fingers into the eyes of Abdulla Beg, whereupon the latter throwing him on the ground, pressed with his chest on Isfandiar Beg’s back and head so furiously that, in two or three places, his adversary’s skin was rubbed off. The Shah’s wrestler then bit Abdulla Beg’s hand; and the latter bit the other’s ears.

Blood began to flow and the spectators became excited, and the Governor-General, seeing that it was not fair play, ordered his head farrash to separate the combatants. They would, however, [158] not separate; so other farrashes were called in, and, by dint of beating both the men, they separated them.

The spectators were now thoroughly excited, some taking the side of the one and some of the other; and a wealthy young merchant from Tehran, who was backing Isfandiar Beg for a large sum, became so furious that he drew his revolver. The Governor-General abused him and told his men to take it away, which was done.

After some words of advice from the Governor-General and the old Sayyid, the two pahlawans took up exactly the same position as at first, and a really fine display of wrestling now commenced. It was evident to every one that Abdulla Beg was gradually getting the better of his opponent, who had lost his wind. He was, in fact, turning him by sheer force on to his back, and the onlookers believed that he had won when a miracle happened; and, before we could collect our senses, we saw Abdulla Beg lying flat on his back.

It happened in this way. When Abdulla Beg was attempting to overturn his adversary, the Shah’s pahlawan got hold of one of his legs with his locked hands and began to turn round and round, when, all of a sudden, pulling the leg inwards and throwing his weight against Abdulla [ p. 159 ] Beg, he overturned him. This was one of those tricks which wrestlers are encouraged to practise in the great cities.

The spectators now got up and all was confusion, some crying that the pahlawans must wrestle again, others shouting that the match was over, until the Governor-General threatened to take strong measures, when comparative calm was restored.

His Excellency then summoned the two pahlawans to his presence, and remarked that both had done very well; he presented a shawl to each man, and, as Abdulla Beg’s arms had not been tattooed, he ordered that a lion should be tattooed on his right arm in memory of this great contest.

The spectators, too, gave gifts of money, and the merchant from Tehran made peace between the two champions and invited them both to a feast, where he compared the Shah’s wrestler to Rustam, and Abdulla Beg to Sohrab, and pleased them both by quoting:

Two Forces, two Arms, and two bold heroes;

One a dragon and the other a lion.

Two fierce tigers or two colossal elephants;

Or two skilful wrestlers.

They began to wrestle,

Holding each other by the waist.

They pressed each other so hard

That breathing became difficult for them.

Several blows were exchanged with such vindictiveness: [p. 160 ]

That the earth quaked beneath their feet.

Each again caught hold of the other,

The one like a lion and the other like a leopard; Both tried their best,

But neither would own defeat.

Each one attempted to overpower the other,

And the desert became muddy with blood.

The wrestling of these two heroes was such

That the names of Rustam and Sohrab were forgotten.