[ p. 221 ]

[ p. 222 ]

¶ BOOK SIX — WHAT HAPPENED IN ISRAEL

I. Judaism

1: The cradle of the Hebrew people — the lure of the Fertile Crescent — Egypt and the Exodus. 2: Moses — the covenant with Yahveh. 3 : How the nature of Yahveh changed in Canaan. 4: The political history of the Hebrews. 5: The work of the prophets. 6: Amos — Hosea — Isaiah — Micah — Jeremiah— Yahveh becomes God. 7: The spiritual exaltation of Israel — the Messianic Promise — its influence during the Babylonian Exile — Deutero- Isaiah. 8: The rise of the priests — -their influence — the new prophets — the Destruction of Jerusalem — the Messianic Dream again. 9: The rise of the rabbis — the Wall of Law- — Judaism today — Zionism — the goy- fearing people— Messianism, the heart of Judaism.

[ p. 223 ]

¶ BOOK SIX — WHAT HAPPENED IN ISRAEL

I. JUDAISM

IN EGYPT thirty-five hundred years ago there was already a great civilization, and magnificent temples were being built there to the glory of the animalheaded gods. In Babylonia there was already a knowledge of writing, and in India the Rig- Veda was already old. The Chinese by that time had so long been established in their land that they imagined they had always lived in it; and the Minoans had already profited by a full thousand years of peace. But the Hebrews, that little people destined to play so large a part in the drama of world civilization — they were still half-savages homeless in the desert.

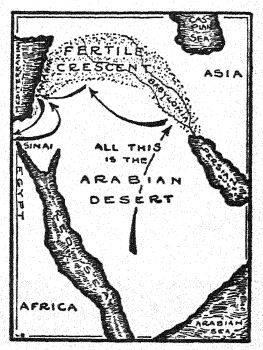

Like the Babylonians and Phoenicians, the Hebrews were Semites, for their cradle-land was that vast wilderness we call the Arabian Desert. Thirty -five hundred years ago the Hebrews were but half-savage tribesmen who lived off the bedraggled flocks and herds which they drove from one oasis to another. And their religion, like the religion of all other primitive peoples, was a barbaric animism. They imagined that all objects [ p. 224 ] around them were possessed of terrible spirits, and their worship was no more than a dark magic-mongering. Fear was very mighty in the bones of those first Hebrews, for life for them was brief and brutally hard. By day their world quivered with the heat of the sun, and by night it shivered because of the cold of the wind. Perpetually their world, the desert, was parched, windstormy, and terrifying beyond words. …

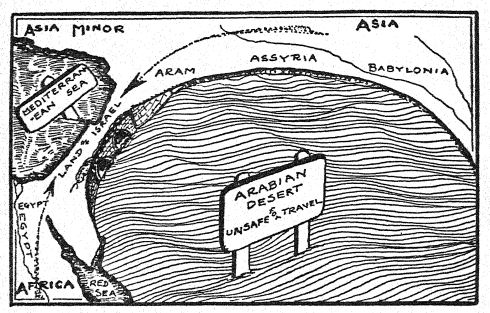

There seemed but one way of escape from the evil which was their life, and that was through migration from the desert. Far to the north there was a great half-circle of verdant soil made up of the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, and the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Modern historians call it the “Fertile Crescent,” and it was the Eden of the desert nomads, the Paradise, the Promised Land. Generation after generation those nomads struggled their way up to its borders, and then by brute force beat their way in. The Fertile Crescent seems never to have been without inhabitants ready to fight off all newcomers. Before the dawn of history it was populated in large part by nonSemitic peoples called the Sumerians and the Hittites. But later it became a region belonging almost exclusively to Semites. Certain tribes out of the desert inundated the eastern tip of the Crescent and became the Babylonians. Others smashed their way into the middle of the Crescent, and became the Arameans. Still others conquered the coastal plain, and became the Phoenicians and Canaanites.

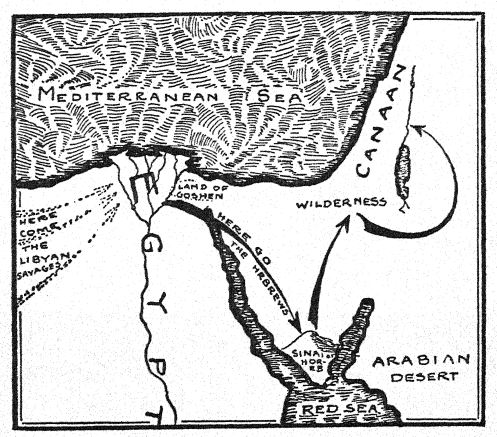

There is reason to believe that the Hebrews, when their turn came to invade the Crescent, tried first to use the eastern tip as the gate of entrance. Only later did [ p. 225 ] they try their fortune in Canaan in the west. (The tradition that Abraham — evidently a tribal sheikh who led one of the first sorties into Canaan — came from “Ur of the Chaldees,” may have that much basis in fact.) Perhaps for many centuries the Hebrews roamed about on the borders of the verdant region, awaiting their chance to break in. Time after time they may have made desperate lunges, murdering and pillaging until they were well inside the Crescent, and then recoiling beneath the blows of the recovered natives. They seem to have gone through such experiences first in Babylonia, then in Haran, later in Canaan, and finally in Egypt. But out of Egypt they were never ejected; they fled! For when they broke their way into Egypt, they got more than they bargained for. They had entered the land in search for- food — but instead they got slavery. From loose-footed bedouins they had been violently changed there into sweating laborers who in chain gangs were forced to build pyramids for the mummified bodies of dead emperors. It was only by taking advantage of a moment when Egypt was desperately trying to fight off hordes of savage invaders from Libya and pirates from [ p. 226 ] the Aegean Islands, that the Hebrews managed to escape. They fled into the wilderness, roamed there as in olden days, and finally made still another lunge at the Fertile Crescent. And that time they managed not merely to squeeze into the coveted region, but also to stay on in it.

¶ 2

IT was out of crisis of the flight from Egypt that the beginnings of a distinctive Hebrew religion arose. Before that time the faith of the Hebrews must have been quite like that of most other Semite bedouins prowling in the desert It must have been a vague and inconstant animism in which the spirits of various mountains and heavenly bodies and oases were placated with sacrifices and spells. Not until the Exodus did it become a definite and differentiated cult.

The leader in that Exodus was a man named Moses, one of the most fascinating and bewildering of the great men of antiquity. Tradition has woven so many threadbare legends around his name that many scholars today are moved to doubt his very existence. But, as in the case of Zoroaster and Jesus and the other ancient prophets, it seems sounder to accept the historicity of Moses than to reject it. Not the historicity of the rocksplitting, Pentateuch-writing, priest-loving Moses of tradition, of course. That is quite obviously a piece of propagandist fiction concocted by the priesthood of a far later day. No, the historicity only of some daring primitive Hebrew who managed to prod his brethren into rebellion against the Egyptians, to appoint himself their chieftain, to weld them into a unit by giving them [ p. 227 ] a god, and finally to get them ready for another desperate effort to enter the Fertile Crescent. Whether he was ever found amid bulrushes by an Egyptian princess, or saw bushes burn unconsumed, or actually turned rods into serpents, rivers to blood, dust to lice, and seas to dry lands — all that is irrelevant. What alone is relevant is the elemental task which Moses accomplished: the giving to the Hebrews of a god. For thereby he founded what was destined to become one of the most exalted and influential of the religions of all mankind. Over eight hundred millions of people —

[ p. 228 ]

[ p. 229 ] full half the population of this believing world — claim to cherish a religion that in definite respects grew out of the religion proclaimed by Moses!

It was far from a perfect faith — this cult instituted by Moses. One must remember that it was founded over thirty-two hundred years ago, by the chieftain of a horde of marauding desperadoes just come up out of bondage. It was just as crude and savage as were the Hebrews themselves. At its root lay the idea that there was but one god — for the Hebrews. For other tribes there might be other gods, but for the Hebrews there was only Yahveh. This Yahveh (or Jehovah, as his name is usually mispronounced) was probably the spirit dwelling in a certain desert volcano called Sinai or Horeb; and from time immemorial he had been worshipped by a bedouin tribe called the Kenites. Now Moses, according to tradition, had once dwelt among the Kenites, and had married the daughter of their chief priest. When it became necessary for his band of runaway Hebrews to be provided with a god, it was therefore only natural for Moses to choose Yahveh. He took his forlorn followers to the very foot of the Holy Mountain of Yahveh located somewhere in the desert, and solemnly committed them there to this god. A covenant was entered into; a holy contract binding the Hebrews to worship Yahveh, and Yahveh to favor the Hebrews. Ten commandments were given as the basis of the worship of the deity; and it was understood that so long as they were observed, the Hebrews could be assured of his divine protection. An “ark” was built as a haven for the roving spirit of Yahveh — it probably was a sort of tribal fetish — and the Hebrews carried it [ p. 230 ] at the head of their columns in every sortie. It cleaved the fear that walled their way, and opened wide a path to triumph. With this “ark” bearing the spirit of Yahveh in their van, the Hebrews beat their way back into the Crescent. When at last they managed to cross the Jordan and wrest from the Canaanites the little land “flowing with milk and honey,” Yahveh, the spirit of a desert volcano, was still their chief deity,

¶ 3

BUT in Canaan the nature of Yahveh was subjected to a great change — for a great change came over his followers. The nomad Hebrews became farmers; from tending sheep they turned to ploughing fields. And since a god is worshipped only because he helps make life less troublous and insecure, because with his aid men believe they can more successfully fight off fear and [ p. 231 ] death, therefore he must change with every change in their life and needs. Yahveh, who had been chosen originally because he seemed able to help men wrestle with the terrors of the desert, was forced to reveal new abilities once his followers settled in a fertile land. He had to do that, or die.

Almost he did die. Throughout the books of Judges, Samuel, and Kings, we see signs of the fierce war of the gods that ensued. Hebrew conquered Canaanite far more easily than Yahveh conquered Baal. Indeed, though Yahveh did triumph in the end, still he never quite crushed his old enemy. The Bible declares: “And they served idols whereof Yahveh had said to them: ‘Ye shall not do this thing.’ ” Long centuries after the first settlement in Palestine, we still find Hebrew peasants worshipping the Baalim on the “high places,” and Hebrew kings passing their children “through the fire” to Moloch. The licentious festivals of the Canaanitish cults were made part and parcel of the cult of Yahveh, and these agricultural rites became dominant in what had once been altogether a bedouin religion.

It is now well established that the so-called “Five Books of Moses” are a compilation of different documents belonging to many different centuries. When these various documents are separated and chronologically rearranged, we can see in them quite clearly how gradual and tortuous was the development of Israel’s religion. The final idea of Yahveh accepted by the Hebrews was not the product of a sudden revelation but of a gradual evolution. Moses did no more (but it was enough!) than preach one great basic doctrine: [ p. 232 ] that Israel belonged to Yahveh. His Yahveh was, of course, far from a gentle, loving, merciful deity. Had he been that sort, he would have been utterly useless to the straggling band of fugitives and desperadoes whom Moses was leading through the wilderness. Yahveh had to be bloody, hard, vindictive in character — even as was the life of his worshippers. He had to be a Lord of Hosts, a god of battle, or else he could be of no value to the embattled hosts of Israel. Only later was Yahveh thought of as a god of mercy and love. Only through the preaching of a long line of mighty prophets did this Thunderer out of the desert, this ruthless Yahveh of a nation of ruthless marauders, become God. . . .

¶ 4

IT is not easy to tell in measured and dispassionate terms of the transformation wrought by those prophets. Above the ruck of fussy priests and slavish worshippers those pioneers of ethical thought stand out so majestic, so tremendous, that it is hard to speak of them save in hyperbole. Had it not been for those few prophets, Israel would today be no more a name than Idumea or Philistia. Had it not been for their insight and courageous labor, Yahveh would have been no more to civilization than Baal-Melkart or Dagon. Sons in blood to Moses, brethren in spirit to Ikhnaton, Zoroaster, Buddha, and Lao-Tze, they loom up in the story of religion as veritable supermen.

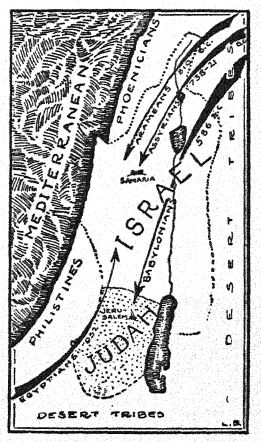

The history of Israel as a political unit was like the history of most of the other little peoples of antiquity. In brief it was this: Under the leadership of tribal priests and sheikhs — “judges” they are called in the [ p. 233 ] Bible — the Hebrews first clawed their way into Canaan, and then settled there. The exigencies of defense against their enemies compelled the tribes to unite under a king. For a while they were highly successful together In warfare, and under David they actually carved out what was almost an empire. But the waste and extravagance of Solomon, who seemed bent on imitating the ostentatious despots of Egypt and Babylonia, brought swift ruin. A revolution ensued, and its close saw the land divided into two kingdoms: Israel and Judah. Israel was situated in the north, and Judah in the south — and in the years that followed, these two tiny kingdoms simply bled themselves to death in incessant warfare. Canaan, their land, lay on the highroad between the empires of the East and West, and invasions by world-conquerors and trading kings were a never-ending source of misfortune. The Hebrews, thus harassed from without as well as within, could not hold out for long. First the northern kingdom, Israel, went down to defeat, and its population was taken captive and deported to Assyria and Media. (That was in 722 B. C., the year from which we date the “loss” of the Ten Tribes.) Then, in 586 B. C., it was the turn of the Kingdom of Judah; its population, too, was taken captive and scattered to the far ends of the Orient. And with that debacle the whole story of the Hebrews came to an end — almost.

¶ 5

BUT then something happened, something extraordinary, almost miraculous. The surrender and annihilation of little kingdoms was a common incident [ p. 234 ] in the ancient world. The Philistines and the Phoenicians and the rest of Judah’s small neighbors were all of them sooner or later drowned in that vortex which was — and is — the Orient But miraculously, Judah cheated that fate. It was harried and butchered, conquered and deported — but of all ancient peoples it alone was never destroyed. Even though one can explain that phenomenon, it still remains a miracle, for the explanation itself can hardly be explained. Even though one can glibly say that Judah’s survival was due entirely to the might of her faith, and that the might of her faith was due entirely to her prophets, yet how is one to account for her prophets? …

The religion of Israel, as we have already said, was a result not of a sudden revelation, hut of a gradual evolution. In the beginning it was crude and simple, a mere cajoling of a desert spirit with sacrifices of blood [ p. 235 ] and flesh. There was as yet no established sanctuary and no professional priesthood. Only after Israel came under the influence of the long- “civilized” Canaanites and Babylonians, did an elaborate ritual arise and along with it a powerful hierarchy. And that foreign influence did not reach its ascendency until after the Babylonian Exile. So that the saving power of the religion — that power which made it at all possible for the Jews to survive the Exile — could not have proceeded from its priestly side. No, the sacrificial cult in Israel was not the cause, but rather one inevitable accompaniment of Israel’s survival. The real cause was the prophetic spirit that had been breathed into the people.

Of the earliest Palestinian prophets, of Samuel, Nathan, Adonijah, Elijah, and the rest, we have little record left save legends. They seem to have been wild evangelists who went up and down the land exhorting the people to remain true to Yahveh. (The Hebrew word nevi-im, “prophets,” may originally have meant “shouters.”) They were the “troublers in Israel” who were forever denouncing the kings for their wickedness, the priests for their venality, and the people for their transgression of the ancient covenant with Yahveh. Again and again they were imprisoned and put to death; but nevertheless they kept right on. In the trying days when the Hebrews were being made over from shepherds into farmers, from tent-dwellers into town-folk, it was those prophets alone who kept the people from being utterly demoralized in the process. We have already referred to the devastating effect of agricultural “civilization” when it first is taken up by erstwhile nomads. If that effect worked extraordinarily small [ p. 236 ] havoc among the Hebrews, it was solely because of the vigilance and zeal of their early nevi-im. Those prophets were the old desert conscience incarnate. They stood unfalteringly against the Canaanite goddesses with their obscenities and lustful rites; they showed no tolerance to the similar cults of Phoenicia, Assyria, and Babylonia. They were Yahveh’s invincible champions in his hard fight to hold the Hebrews from worshipping Baal, Moloch, Ashtoreth, and all the other gods and goddesses of Asia Minor.

¶ 6

BUT although the prophets labored so intensely to keep the old Yahveh on his throne, they did more to destroy him than even the priests of the rival deities. When they were done keeping him on the throne, he was no longer the same Yahveh at all. Although the prophets set out only to revive the ancient faith, actually they did not revive it so much as totally reform it. They reformed Yahvism from end to end, so that when they were done it was no longer Yahvism at all — it was Judaism! They transformed a jealous demon who roared and belched fire from the crater of a volcano, into a transcendant spirit of Love. They took a bloody and remorseless protector of a desert people, and without realizing it, changed him into the merciful Father of all mankind. In fine, they destroyed Yahveh and created God!

Read intelligently — that is, critically — the Bible makes that course of evolution strikingly clear. The Hebrews settled in Canaan in about the twelfth century B. C. By the eighth century the simple nomadic religion [ p. 237 ] they had brought with them had been almost entirely superseded by an agricultural cult. Especially was this true in the northern kingdom, Israel, where “civilization” was further advanced. There morality had been completely ritualized by the priests, and it had come to be firmly believed that animal sacrifices to the deity could atone for the most heinous crimes against man. What had happened in Egypt.

Babylonia, India, and almost everywhere else, had happened also in Israel; the deep-seated tendency of human nature to rely on religious rites as the source of safety and security had led once more to the triumph of the priest.

Corruption was regnant, and tyranny seemed to be right beyond challenge.

And in a land where such a religion went unquestioned, there suddenly appeared a strange man named Amos. He was an unknown sheep-herder from the hills in the south, and at one autumn festival he arose in a temple where the nobles and priests of Israel were revelling in sacred license, and cried:

[ p. 238 ]

Hear this, you who trample upon the needy,

and oppress the poor of the earth. . . .

The Lord Yahveh hath sworn by his holiness:

‘Behold, days are coming upon you when

you shall be dragged away with hooks, even

the last of you with fish-hooks !’

He cried out much more in that same strain. He whipped the drunken worshippers with his scorn, and terrified them out of their sordid smugness with his prophecies of an inevitable doom. What they did to him for his daring, no one knows. Perhaps they put him to death; or perhaps they let him preach on, thinking him but a noisy dervish. For so soon as the passion that went into their utterance was spent, those words must have seemed to the Israelites no more than the ravings of sheer lunacy. No one until then had ever dared to declare that Yahveh himself might punish his own folk. The belief was rooted that, so long as Yahveh was fed with enough sacrifices, there was no possible chance of his failing to protect his people. He would fight their battles for them, water their lands, fecundate their cattle, and prosper their deals. The novel idea that the god was revolted by such things as social crimes, by the perverting of justice or the exploiting of the poor, or by wine-bibbing or harlot-chasing must have been totally incomprehensible to the gentle folk of Israel twenty-eight hundred years ago!

Yet that was just the idea that Amos, a simple peasant from the hills of Judah, dared to cry out in the temple at Beth-El. He declared it was all wrong to believe that Yahveh was a mere tribal possession, a monoply of [ p. 239 ] Israel. If Yahveh had brought the Hebrews up out of Egypt, behold he had also brought the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Arameans from Kir. Indeed, the Hebrews, Amos declared, had no more chance of currying undue favor with Yahveh than the black-skinned Ethiopians! … So all hope for special indulgence was vain. Yahveh was remorselessly a god of Justice, and if Israel continued to rely on ritual rather than righteousness, then he would destroy the nation root and branch for its sin! . . .

And thus was attained the first rung in the ladder which brought Yahveh up to the Throne of God. Yahveh was now no more a mere glutton for sacrifices; he was the inflexible Commander of Justice. . . .

The ascension of the second rung must be credited to another prophet, Hosea. He appeared shortly after Amos, and in that same northern kingdom. He, too, was well acquainted with the wickedness that prevailed in Israel, and he, too, was convinced of the impending doom. But he, unlike Amos, saw a chance, a belated yet nevertheless certain chance, for Israel to be saved. For Yahveh, who to Amos had been wholly an inexorable Commander of Justice, was to Hosea also a Father of Love. Yahveh was merciful as well as just, and knew how to forgive. Therefore, said Hosea, if only Israel would repent, of a surety Yahveh would spare the land. . . . .

But Israel did not repent, and within a generation the kingdom met its end. The doom came, and the ten tribes of the North were hounded out of the land of their fathers into the oblivion of endless exile. After 722 B. C. only Judah was left, and the rest of the ascent [ p. 240 ] of Yahveh to the altitude of God over all the earth was achieved in and around the city of Jerusalem. Quick and dramatic became that ascent, as prophet swiftly followed prophet. First Isaiah appeared, and through his preaching the majesty and omnipotence of Yahveh became established. The natural tendency of the priests to make their rites superior to the gods was by him effectively frustrated in Judah. In India, Babylonia, Egypt, and wherever else the power of the priests was allowed to grow unchecked, the gods were almost unfailingly debased and made as slaves. But in Judah that evil was averted through the labor of prophets like Isaiah. They made it glaringly plain to the people that not all the sacrifices on earth, nor all the magic spells, could exercise the slightest coercive power over Yahveh. As Micah, another prophet, put it tersely:

What doth Yahveh require of thee?

Save to do justice, to love mercy,

And to walk humbly with thy God . [1]

But the process did not end even there. There was yet to come a prophet greater than all who had gone before him. In the most trying years of Judah’s history, when the little land was making its last mad and futile stand against Babylonia, there came that mighty prophet named Jeremiah. And he dared to exhort his people to put down their arms and submit. Vain was it for them to resist, he declared, for Yahveh was not on their [ p. 241 ] side. On the contrary, He was on the side of the enemy, and Nebuchadnezzar of Babylonia was but His instrument. For Yahveh was not the mere godling of the Hebrews; He was God of all the earth! He could do as He willed not merely with one nation, but with all. Indeed, He was the Founder of all nations, the Creator of all the earth! . . . Amos had not been able to get nearly so far as that; neither had Hosea nor even Isaiah. Only with Jeremiah was the claim clearly made that there were no other gods save God. There was no Asshur for the Assyrians, Dagon for the Philistines, Bel for the Babylonians, or Osiris for the Egyptians; there could not possibly be any local deities with fortunes inextricably bound up with the fortunes of their own nations. There was only —God!

And thus at last, toward the end of the seventh century B. C., Israel’s religion became truly a monotheism. Thus at last Yahveh really became God!. . .

¶ 7

BUT side by side with this exaltation of Yahveh came also the self-exaltation of Israel. It was inevitable. Having declared their Yahveh to be the Supreme Ruler in heaven, it was logically necessary for the Israelites to [ p. 242 ] declare themselves to be the chief nation on earth. And they did just that. Despite recurrent defeat and humiliation and exile, the Jews persisted in thinking themselves the Chosen of God. Of course, the prophets, every one of them, encouraged that thought. Even though they denounced their fellow Hebrews and heaped scorn on them for imagining they could curry favor with Yahveh, those prophets themselves never ceased to declare that the Hebrews were still the Chosen of Yahveh. Only they insisted that the Hebrews were chosen not for special indulgence but solely for the task of bringing the knowledge of this Yahveh to all the world. They promised that if the people would but accomplish that task, then lo, they would indeed be the first nation on earth! Their truth would conquer all mankind, and the whole earth would be a Paradise in which their own Messiah, their “Anointed One,” would reign as “Prince of Peace!” . . .

It proved an astoundingly potent force, that promise. It became the very heart of Israel’s religion, giving it color and warmth and life. It accomplished the one fundamental purpose at the root of every great religion, for it offered its followers a reason for remaining alive. The Jews believed in that Messianic promise implicitly and unhesitatingly; and believing in it, they were saved by it. In the dread days of exile, when they sat by the waters of Babylon and wept, that promise was the one thing that kept them alive. For its sake they braced up and preserved themselves as a people, cherishing the memories of their past, and incessantly planning for their future. All during those slow bitter days in Babylon their leaders seem to have busied themselves with [ p. 243 ] preparations for the great triumph to come. They made collections of the legends recounting the exploits of their ancient patriarchs and prophets and kings, writing down on scrolls the countless glowing tales that had been handed down by word of mouth for twenty generations or more. They also gathered together all their old laws, and elaborated them so that they might fit new needs. Modern scholars are convinced that much of the material in the “Five Books of Moses” was written, and all of it was first edited, not before, but during and immediately after, the Babylonian Exile. No doubt that is why we find in the Pentateuch so many myths and taboos and priestly laws that strikingly resemble those of the Babylonians. It must have been impossible for the Jews to resist the influence of their environment. Seeing priestliness rampant on every side in prosperous Babylonia, the exiles naturally breathed a measure of it into the books they were preparing for their own soon-to-be-prosperous Zion.

But this law-code, despite its dominantly priestly [ p. 244 ] character, depended for its conception and birth on the prophetic urge. (That was why, for all its similarity, it yet managed to differ so fundamentally from the Babylonian code from which it had been derived.) This Jewish law-code was prepared solely in anticipation of the day when the old Messianic promise would be fulfilled. No one seemed to know just when that day would come; but all expected it in the near, the very near, future. And the greatest prophet of the exile, that unnamed genius whom we call Deutero (the Second) Isaiah, pictured the glory of that day in words that the Jews never forgot. He brought the self-exaltation of Israel to its climax, investing the future of the people with a dignity and a significance such as no earlier prophet had dreamed of. According to this unnamed prophet, the whole people of Israel was the Messiah, the “Anointed One.” All Israel was the “Suffering Servant of the Lord,” the “light unto the Gentiles, that the Lord’s salvation may be unto the end of the earth.”

In this character Israel was destined to he utterly triumphant, promised the prophet. What other nations without number had tried and failed to accomplish with the sword, Israel would succeed in doing merely with the Word of God. And thus the Jews would ultimately be victorious over all the earth: their spirit, their ideals, their God, would reign supreme. Jerusalem in that perfect day would be the center of the world, and its Temple would become a house of prayer for all nations. They, the despised Jews, now scattered and broken and regarded with contempt — they in the end would be the mightiest conquerors of all! . . .

[ p. 245 ]

Such was the gospel of that unnamed Jew whose words are recorded in Chapters 40 to 55 of the Book of Isaiah. By contrast that gospel appears almost incredibly high and hopeful. In that same century, six thousand miles away in China, Confucius was plodding from village to village in futile search for a prince who would bring back the past. All that was glorious seemed to him to have already been, and all that was right seemed to belong only to yesterday. … In India, almost three thousand miles away, Mahavira the Jina, and Gautama the Buddha, were groping in jungle fastnesses, seeking not a prince to bring back the past, but a principle of circumvention that might aid them to elude the future. All the past seemed to them to have been as bad as the present, and the future looked to be no whit better than the past. The whole cycle of life seemed one long-drawn-out weariness to the flesh, an abomination to be destroyed at any price. . . . But there in Babylonia stood this homeless Jew, he who had every right to mourn for the past and tremble for the future, he who should have been the most dejected and despondent of souls — there he stood, happy, exultant! There was no trace of despair in his soul. On the contrary, he was full of hope, of mad, ecstatic hope for the Great Release to come. Not release from life, but for life; release for life nobler, richer, more abundant than it had ever been before. “Comfort ye, comfort ye, my people!” he cried. “Fear not, thou worm Jacob. I shall help thee, saith the Lord. Behold, thou shalt yet thresh the mountains, and beat them small; yea, thou shalt make the very hills as chaff!”

So cried this Unknown Prophet of the Exile. . . .

[ p. 246 ]

¶ 8

AND then, almost immediately, came the release — or at least its beginning. In 538 B. C. Cyrus of Persia conquered Babylonia and set the exiles free. The Jews were free then to conquer the world — with the word of the Lord.

But the glorious conquest began most ingloriously. When the Jews returned to their own little land, they took back with them the law-code which their scribes had prepared for them in exile. And, as we have already said, it was in effect a priestly code. From then on, therefore, the voice of the prophets grew fainter and fainter, and the chanting of the priests grew ever more strident. What happened in India, China, Persia, and every other “civilized” land, happened also in Judea. Instead of seeking to win God’s favor and save themselves by doing justice and loving mercy, the Jews tried to accomplish those ends by offering sacrifices and mumbling prayers. (It was much less difficult a technique to try.) And thus the priests were brought into power. The priests were the chief sponsors for the easier technique, and therefore they were vastly enriched by its popularity. The more the people sought to bribe their way to God by means of priestly ritual, the more the priests rose in might. There was no escaping that sorry development, for the masses were not yet ready to follow the high commands of the prophets. They were ready only for the little laws of the priests, for the petty rules made by those men of petty spirit who imagined they could organize morality.

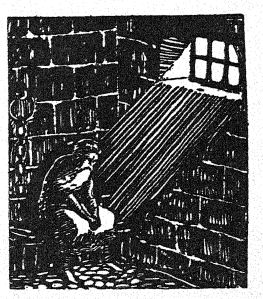

It is quite possible that in the beginning those priests [ p. 247 ] were most sincere in their labors. Perhaps they believed they were being utterly true to the prophets when they sought to organize prophetic truth. But in a little while they became so involved in the process of organization that they began to lose all sight of the truth. The means became more important than the end; the how overwhelmed the why. The labor of the prophets, that fury of preaching that had somehow dragged the cult of a marauding desert- folk up hill until it became the superlative ethical faith of the ancient world, was now bit by bit undone. For almost six hundred years after the return from Babylonia, the priests let the religion of Israel degenerate into an ever more ritualized morality. Indeed, if during those six hundred years the religion did not degenerate entirely, it could have been only because prophetic protest, though intermittently choked, was still never quite strangled. Ever and again isolated prophets arose to decry the sacerdotalism and corruption of the priests and people. Some of them were beheaded, like John the Baptist; and some were crucified, like Jesus of Nazareth. But they came nevertheless, an unbroken succession of heroic and godly protestants. It was the old promise of the Messiah that spurred them on. Despite all the agonies and humiliations they endured in those years, despite all the outrages visited by Persian, Greek, Syrian, and Roman overlords, some Jews still believed that they must be triumphant in the end. Always a remnant of the tiny folk looked forward to the immediate coming of the “Anointed One,” to the speedy coming of the Kingdom of God. Indeed, the more dreadful and crushing their plight, the more frenziedly this saving remnant looked [ p. 248 ] forward to that advent. Throughout the land there went strange men as its spokesmen, crying to the people: “Repent ye, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand!”

But though it seemed ever at hand, it never came. Darker and darker grew the world of the Jews as the vast black wings of Rome dosed down over it. Israel writhed in the bloody talons of the Empire for more than a century. And then, goaded almost into insanity, Israel rebelled. Tired of waiting for the Messiah, the Jews tried to force the day of His coming. The whole country flared up in rebellion, and Israel made its climacteric effort to preserve itself as a nation. Two of Rome’s greatest generals were sent down to quell the uprising, and for four years every wady in the land ran red with the blood of the slain. For many months the holy city of Jerusalem was besieged; and when finally in the summer of 70 A. D. it was captured and destroyed, the Jewish nation was destroyed too. The dread Diaspora, the “Scattering,” began in earnest then. The Jews either fled or were hounded to the uttermost ends of the earth, and the glory which was Zion was ended, it seemed, forever.

But it was not ended. Not at all. On the contrary, it but began then anew. Though the Temple was destroyed, and the whole sacrificial cult had become a thing of the past, Israel still continued to live. For the one great promise of the prophets was still effective, even though the little laws of the priests were now null and void. Even after the Dispersion the Jews continued to cherish their dream of the Messiah. It may have been an irrational dream, ridiculous, altogether mad — but it persisted. And so long as it persisted, the Jews persisted. [ p. 249 ] Even to this day it persists. It has been denounced and betrayed, attacked and violated — but it has never been quite forgotten.

¶ 9

THIS is not the place for a detailed account of the history of the Jews during the last nineteen centuries. One wishes it were, for that history is like none other in all the saga of religion. The story of the Parsees, those exiled descendants of the ancient Zoroastrians, comes perhaps closest to it; for that people, too, persisted because it cherished a hope. But save for the little group of Persians still awaiting the triumph of Ormuzd, none other is to be likened to the Jews. The Jews stand out among the races of the world, a strange, an inexplicable folk, with a history far stranger than fiction.

But at least a hint as to that history must be given here. When the Temple was destroyed and the old priestly cult was ended, the whole technique of the religion had to be radically altered. The priestly organization was no more, and a new organization had to be created. So the rabbinical cult resulted. A gigantic legal literature called the Talmud was developed in the first five centuries after the Destruction, and later an even more gigantic literature of Talmudic commentaries and super- commentaries. It is not difficult to explain why the development took such a form. The prophets had for all time answered the why of life for the Jew. They had said that for a while he must live and suffer so that ultimately he might triumph, so that ultimately he might bring on the Kingdom of God. But those prophets had been far from explicit as to the more immediate [ p. 250 ] matter of the how. Granted there was a purpose in life, yet how could the Jew keep alive long enough to realize it? He saw himself to be quite helpless in that whirlpool of races and creeds which is the world. He had no home, no might, no prestige — nothing save an ineluctable belief in his own importance to mankind. And that by itself was far from enough to keep him afloat in the whirlpool. So he began to tremble for his very existence. Fear took hold of him almost as acutely as once it had taken hold of his savage ancestor in the wilderness. But whereas fear drove the savage to have recourse to fetishes, it impelled this remote descendant to take to laws. The savage had tried to save himself from drowning in fear by conjuring up reeds of magic to which he could cling. For exactly the same reason the Jew built up a dyke of law behind which he could hide.

It was that Wall of Law that saved the Jew from destruction after his own home was destroyed. It kept him apart from the Gentiles, regulating his prayer, his food, his very raiment, so that he could never for a moment forget his identity. The dream of the prophets made life reasonable for the Jew, but only the lawcode of the rabbis made it possible. And so long as the Gentile world kept fear palpitating in the heart of the Jew, so long that wall stood firm and unbroken. If it is crumbling visibly in our day, it is largely because the world is growing less intolerant, and the fear in the heart of the Jew is being dispelled. If the old Orthodox Judaism is disintegrating in our day, and “Reform” or “Liberal” Judaism is growing, it is because the wind of emancipation is sweeping the soul of Israel free of dread.

[ p. 251 ]

But there is no certain assurance that that process is going on with any rapidity. Of the sixteen or seventeen million Jews in the world today it is doubtful whether even two million of them are unhindered by orthodox taboos and scruples. Intense fear of the goy, the Gentile, still lingers in the soul of the Jew, be he a dweller in Washington or in Warsaw. A terror pounded into him incessantly for twenty or thirty centuries can hardly be dispelled in a generation. No, fear is still tormenting the Jew, and as fast as the Law is crumbling, he is building a new wall — or rebuilding an old one — of nationalism. In spirit, if not often in body, he is now returning to old Palestine. At least, his young men and maidens are returning there, to tread once more the soil of Amos and Jeremiah. And thus through a recreated nationalism is the contemporary Jew seeking to save himself from extinction.

So it is on the now familiar motif of fear that we must close this book, too. The Jew clings to his ritual law largely because he senses subconsiously that otherwise he will lose his identity among the non- Jews. In other words, he is God-fearing largely because he is Goyfearing. But it should be noticed that this fear at the heart of Judaism is generically different from the kind that nourishes most other religions. It is fear not for the destinies of the individual, but of the group. Until the Jews were brought into contact with the Zoroastrians, they seem to have had no notion of individual immortality. Until then, the hunger of the Jews seems to have been only for national immortality. And even though the idea of a personal after-life has since struck deep root in Judaism, the earlier idea still remains the [ p. 252 ] more important. The Jews still seem far more concerned about their future as a group than as individuals. No doubt that is why they have been so willing all these centuries to suffer persecution and death rather than forswear their faith. Their religion has taught them that as individuals they do not count; that only as members of the Jewish group do they possess any dignity or significance. And accepting that teaching implicitly, the Jews have managed to survive twenty centuries of the bitterest oppression ever visited on any folk on earth. Not merely have they survived; in a measure they have even flourished. They have so grown in numbers and advanced in power that they are to be found in conspicuous positions almost everywhere in the world. And wherever they dwell they are as a leaven in society, stimulating an incessant ferment of prophetic protest and rebelliousness. Oppression, far from weakening them, has only tempered their spirit. Like a sword the Jew has been stretched out on the anvil of history and with every blow has grown only more resilient and durable.

And it is the Jew’s religion, his certainty of an ultimate deliverance from the Gentiles, his faith in a Messianic future for his people, that has made the miracle of his survival possible. The Jew seems almost organically incapable of forgetting that high-born promise made to him by his prophets twenty-five centuries ago. He still believes, albeit unconsciously, that it is nis duty to keep alive because he has a mission to fulfil. His Bible, his daily prayers, even his folk-songs and fairy-tales, all beat into his soul one obsessive belief: that he is preeminently the sword of the spirit that shall yet clear [ p. 253 ] the way for the coming of the Kingdom of God! That may very well be a foolish, an irrational, a presumptuous belief — but so is every other in all this believing world of ours. All religions are built on one utterly undemonstrable and apparently irrational dogma: that somehow and somewhere some human beings may yet be able to cope with the universe. Therefore Judaism cannot be said to be more presumptuous than any other religion in its basic conviction. It can only be said that the Jews seem more closely bound and more firmly sustained by their conviction than the adherents of most other religions. But that, far from revealing a defect in the Jew’s religion, proclaims what is probably its chiefest virtue: Judaism works. …

¶ Notes

That oft-quoted verse from Micah is profoundly significant. It epitomizes the contributions of Amos, the prophet of justice, and Hosea, the prophet of mercy, and Isaiah, the prophet of heavenly majesty. In a scorn of simple words it tells the whole story of the exaltation of Yahveh and the moralizing of Yahvism. ↩︎