[ p. 255 ]

[ p. 256 ]

¶ BOOK SEVEN — WHAT HAPPENED IN EUROPE

I. Jesus

1: Palestine in the first century — the Zealots and saints. 2: The childhood of Jesus — youth. 3: John the Baptist— Jesus begins to preach. 4: His heresies — his tone of authority — did Jesus think himself the Messiah? 5: Jesus goes to Jerusalem — falls out of favor — is arrested, tried, and crucified. 6 : The “resurrection” — the disciples begin to preach. 7: The religion of the Nazarenes — the growing saga about Jesus.

II. Christ

1: The mysteries in the Roman Empire — the philosophies. 2: The story of Saul of Tarsus. 3: The work of Paul. 4: Jesus becomes the Christ — the compromises with paganism — the superiority of Christianity — the writing of the Gospels — persecution by Rome. 5: Constantine and the triumph of Christianity. 6: The cost of success — the schisms. 7: The spread of Christianity — the ethical element in Christianity — how it sobered Europe. 8 : The development of the Church — Protestantism — why Christianity has succeeded.

[ p. 257 ]

¶ BOOK SEVEN — WHAT HAPPENED IN EUROPE

I. JESUS

SORE was the travail in Israel because of the oppression of the Romans. Armies thundered up and down the countryside, ploughing a bloody furrow wherever they went; and spies slunk about in the alley-ways of the towns, carrying slander and dealing death as they moved. Rome, the mighty power that could conquer whole continents, could not possibly keep tiny Palestine in check. Rome could not fathom the Jews, could not understand their maddening obstinacy and rebelliousness. She could not understand why the Jews went mad at the thought of worshipping the images of emperors, or why they deafened the world with lamentations when their Temple money was used for building aqueducts. And naturally, therefore, Rome lost all patience. At the least remonstrance she hacked at the Jews mercilessly, not reckoning what whirlwind might rise from the enforced order she sowed. …

And the Jews, racked with pain beyond bearing, weak from loss of blood, went almost mad. They had [ p. 258 ] come to an impasse in which they knew not what to do. They dared not surrender, for they still cherished their ancient Messianic hope. Despite all the terror that had been their lot almost from the day of their creation, the Jews still believed that their Anointed One, their Messiah, would come, and that with Him would be ushered in the Kingdom of God on earth. On this score there seems to have been no division among the Jews. Only as to the means of bringing on the Great Day, was there any division. As to that, some of the Jews counseled war, and others counseled prayer. They who were strong of body and fiery of temper could look forward to no salvation save one wrested by the sword. These were called Zealots, and they went up and down the land attacking lone Roman garrisons, murdering Roman sympathizers, plotting, protesting, fighting, dying, all to bring on by brute force the Reign of Peace. . . . And what they brought on in the end was only a bloody debacle, a final conflict that simply wiped out the Jewish nation and scattered its hapless survivors to the four corners of the earth. . . .

But those who were strong of soul rather than body sought to win salvation by quite other means. To them it seemed that the Reign of Peace would be brought on only by ways of peace, and they therefore cried to the people to rebel against their own doings rather than the doings of Rome. They begged the people to purge their own souls of sin, to crush their own lust for power and vengeance, to be humble and meek of spirit, to ba loving and forgiving, to return good for evil, and thus quietly, prayerfully, to await the wondrous day of [ p. 259 ] reward to come. . . . And in the end those preachers of peace somehow helped give rise to a new religion, a great faith which, though it never brought release to Israel, did bring salvation to half the rest of the world. . . .

¶ 2

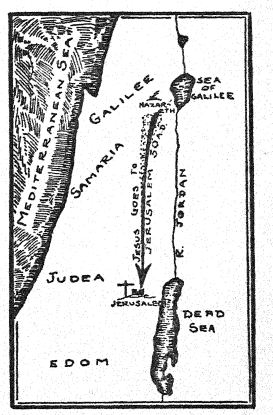

THE prologue of the story of that new religion opens in Galilee. Almost two thousand years ago there was born in the Galilean village of Nazareth, a Jewish child to whom was given the name of Joshua, or Jesus. We do not know for certain how the early years of this child were spent. The Gospels recount many legends concerning his conception, birth, and youth, but they are no more to be relied on than the suspiciously similar legends told many centuries earlier about Zoroaster. In his youth Jesus seems to have followed the calling of his father, and was a carpenter. His schooling had probably been slight, for his people were humble villagers, and in all Galilee there was notoriously little learning in those days. He cherished many of the primitive notions of the simple folk to whom he belonged, believing that disease and sometimes even death were caused by the presence of foul demons, and could be removed by prayer. He knew little if any Greek, and could never have even heard of Greek science or philosophy. All he knew was the Bible, and probably the text of that had been taught him only by rote. Like every other Jewish lad, he had been made to memorize the ancient prophecies in the Bible, and to keep the Biblical and Rabbinical laws of his time. Above all he must have been taught to prize as dearer than life the [ p. 260 ] old obsession of his people that some day they would be miraculously freed by the Messiah. Indeed, so well was that last drilled into him that, as he matured, the hunger for the realization of the hope became his allconsuming passion. It seems to have given him no rest in that sheltered little village where he plied his craft. He could not sit by and patiently wait. He had to take staff in hand, and go out and do what he could to hasten the coming of the Great Day!

There was nothing extraordinary in such conduct. As we have already seen, Palestine then swarmed with young Jews bent on a similar mission. Most of them, of course, joined the Zealots, and went around fomenting war against Rome. There were others, however, who counselled only peace with God, and it was to them that the simple Galilean carpenter joined himself. It must have been a queer company that he fell into. Most of those preachers of peace were burning evangelists who, in imitation of the ancient prophets, had clad themselves in camel hair and leather girdles. Soma were obviously mad: wild-eyed, tousle-haired, [ p. 261 ] frothy-lipped epileptics who rushed about screaming meaningless chatter in the ears of all who would listen. Others, however, were just as obviously of that type which throughout history has given us our prophets and geniuses: that madly sane type whose members so often are stoned while alive and enthroned when dead. . . . But insane and sane alike, they were all in a white heat to get the people prepared for the swift coming of the Messiah. Up and down the land they went, crying: “Repent ye, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.” And they stood on the banks of the Jordan and immersed the repentant in its holy waters. It was terribly important, according to these evangelists, that one should be thus baptized in the Jordan, for thus alone could one be proved worthy of inheriting the Kingdom of God on earth. They declared that all who were caught unbaptized — that is, uncleansed of evil spirits — when the Messiah came, could never, never know the joys of the Millennium. …

¶ 3

NOW at this time there was in the land an evangelist so successful in drawing the people to the Jordan that he had come to be called John the Baptizer. He was a rough, ascetic person who lived on locusts and wild honey, and who clothed himself in animal skins: a veritable re-creation of the ancient prophet Elijah. To him it seemed that yet another day, another hour, and behold, the Kingdom of Heaven would be here! . . .

It was to this John the Baptizer that Jesus came when he left his home in Nazareth. For a time he was a follower of John, one of a multitude of young Jews [ p. 262 ] and Jewesses who believed in the mission of the wild prophet and tried to aid him in his work of saving souls. But when a little while thereafter John was imprisoned for his denunciation of the reigning tetrarch, Herod Antipas, Jesus went back to Galilee and began to preach by himself. His gospel was much like that of his teacher. “The time is fulfilled,” he cried, “and the Kingdom of God is at hand. Repent ye!” So did he cry wherever he could find ears to hearken. He went to the beach of the Sea of Galilee, where the fishermen could be found at their labor; he went into the synagogues in the villages, where the pious and the proper folk could be found at their worship; he even went into the houses of shame, where he could reach the publicans and sinners. And wherever he went, few could resist his eloquence. There must have been some quality in his bearing, something in the intensity of his spirit and the earnestness of his preaching, that simply compelled the harried Galileans to give ear. And giving ear, drinking in the words of comfort which he uttered, they could not help but believe. And believing, accepting wholeheartedly the promise which he made, they could not help but feel saved.

When the stories of that young preacher’s wanderings were gathered together in later years and set down in writing, it was said that he performed all manner of miracles as he went about the land. Perhaps there is a fragment of truth in that tradition, for if people will only believe with sufficient faith, miracles become not at all impossible. The blind — if their eyes have not been taken right out — will be able to see, and the halt — if their limbs have not been torn away — will be able to [ p. 263 ] walk. The working of such wonders has been ascribed to almost every great prophet and saint in history, and even allowing for the inevitable exaggeration brought on by enthusiasm and time, there is still left a core of truth that cannot be discounted. Implicit faith, which on ten thousand and one occasions has made even a medicine-man’s dance effective as a medium of cure, could not but make effective a prophet’s hand. . . .

And Jesus could quite command implicit faith. He himself believed; with all his heart and soul he believed that soon would come the Great Release. So the poor Jews and Jewesses of Galilee, the simple fishermen and farmers’ wives, the blear-eyed publicans and low women of shame, were compelled to believe with him. They could not possibly resist. For this young man brought them in their distress their only ray of hope. Without that promise which he held out, their life was left one hellish gloom. There they were, starved, sweated, diseased, and full of fear. Wretched peasants and slumdwellers that they were, they had nothing whatsoever to live for, nothing — save that promise which Jesus proclaimed.

So they hearkened and believed and were saved. By the score, by the hundred, they flocked to hear him, plodding many a weary mile through the dust of the hilly roads to stand at last before him and hear his words. He spoke without the slightest flourish, using plain words and homely parables. He indulged in no philosophy or theology, for, after all, he was an untutored toiler who knew nothing of such vanities. Nor, seemingly, did he preach any inordinate heresies. Unlike Buddha, to whom he is often compared, he did not [ p. 264 ] preach a radically new gospel. “Think not that I am come to destroy the law or the prophets” he declared. “I am not come to destroy but to fulfil.” His prayers were made up of verses which the Pharisee rabbis were wont to recite in the synagogues, and which are to be found even today in the orthodox Jewish book of prayer. His garb, even to the wearing of the fringed hem, was the garb of an observant Jew. He actually went out of his way to pay the Temple tax to the priests, and saw no absolute wrong in offering sacrifices. No, he was not a heretic in the sense that Ikhnaton or Zoroaster or Buddha were heretics. Outwardly he was distinctly a conforming Jew.

¶ 4

YET for all his conformity in these and other respects, Jesus was definitely a rebel. Like most of the great prophets who had preceded him in Israel, he scorned the rich and the proud, the priests in the Temple and the rabbis in the synagogues. His heart went out only to the downtrodden, to those sorry wretches who could win their way to God neither with costly sacrifices nor erudite learning. His whole gospel was intended but to comfort the disinherited, for it declared that no matter how unlettered they might be they could nevertheless be taken into the Kingdom of God when it came. For it was repentance alone, according to Jesus, that could make one eligible for entrance into that Kingdom. Indeed, wealth and pedantic learning, he declared, were hindrances; only purity of heart was of any worth.

Now such a gospel was literally saturated with heresy. Because it denounced the rich and commanded them to [ p. 265 ] divest themselves of all their possessions, it attacked the whole sacrificial cult. For that cult, with its priests and levites, its elaborate T emple and costly parade, depended entirely upon wealth for its existence. A people without possessions could never possibly afford fat bullocks to buna or skins of oil to pour away. Besides, if purity of heart was the sole credential of any avail, what sense was there in offering any sacrifices? . . . Moreover, because this gospel minimized the importance of learning, and commanded men to keep merely the spirit of the law, it attacked the whole Rabbinical cult For that cult, created by the Scribes and Pharisees, depended on scholarly knowledge of the letter of the law for its importance. The “Wall of Law” of the rabbis had been built out of the involved interpretations and reinterpretations of every word in the Pentateuch; indeed, of every letter and of every illumination around each letter in it And it seemed to many of the rabbis that only one who knew that Pentateuch word for word, and all the innumerable interpretations thereof, could possibly be a righteous soul. Many of those rabbis despised the “man of the earth,” the peasant, saying that his ignorance of the minutiae of the law was a millstone that dragged him down to the level of the heathen. Obviously, therefore, this gospel of Jesus declaring that the “man of the earth” could be the very salt of the earth, was charged with quite devastating heresy.

But the heresies of Jesus were not at all without precedent in Israel. Innumerable prophets had arisen before his time to attack the greedy priests; and the very rabbis themselves reviled in their Talmud the hypocritical and bigoted in their midst, calling them “the Pharisaic [ p. 266 ] plague.” What really marked Jesus as one unlike any preacher that had come before him was not so much what he said, as the authority on which he said it. His tone was altogether novel in Jewish experience. Every other prophet had uttered his heresies in the name of God. “Thus saith the Lord,” had preceded their every declaration. But this carpenter from Nazareth, for all his meekness and humility, spoke only in his own name. “Take my yoke upon ye,” he said. . . . “Whosoever shall lose his life for my sake,” . . . “ye have heard that it was said of old time . . . but I say unto you . . .” So did he speak, not as the mouthpiece of God, but as one vested with an almost divine authority of his own.

It was that tone which in the end cost Jesus his life. The priests and scholars must have been incensed by it beyond bearing. Such a tone would have sounded blasphemous to them even in a prince or a learned man. In an untutored laborer, in a peasant from benighted Galilee, it must have seemed the most outrageous impudence. . . . But it was that tone, after all, that endowed Jesus with his striking magnetism. It created and sustained the impression that he was a transcendent person, and bestowed on him the power to take cringing serfs and make them over into towering men. Only because he believed in himself so firmly, only because he was so superbly confident, could he make others accept his words. His tone was not that of a mere prophet, but almost that of God Himself. And that was why men began to say he was more than a man, that he was the Messiah! It was not merely that he could perform what were thought to be miracles, casting out demons and [ p. 267 ] raising the dead — though such reputed powers must have furnished the most convincing proof to the majority of his peasant followers. It was more that he could carry himself with the divine assurance of an “Anointed One,” casting out fear and inspiring the living.

Whether Jesus himself was convinced he was the Messiah is a problem still unsolved. His refusal to make the claim in public, the almost too astute way in which he avoided a direct answer whenever the question was put to him, presents to this day a dilemma to the faithful. But it is certain that many of those who followed Jesus believed h im to be the Messiah. The sight of that ragged young Jew hurrying beneath the hot sun of Galilee, poor, unlearned, yet able to breathe a perfect frenzy of hope and cheer into vast throngs of forlorn derelicts, must have seemed proof indisputable that he was indeed the “Anointed One.” There was a wondrous love in his preaching and, coupled with it, an air of certainty, of authority. For five hundred years some Messiah had been awaited, and more than once it had been men of the basest stuff that had been mistaken for Him. Charlatans and madmen, arrant knaves and driveling fools, had time and again been hailed by the hysterical mob as the Awaited One. Is it any wonder, therefore, that an exalted person like this young carpenter, Jesus, should have been hailed likewise i . . .

¶ 5

THAT Jesus was indeed an exalted person is hardly to be doubted. Even when one has discounted all the [ p. 268 ] legends, all the stupid and silly and gross extravagances, all the pious embellishments and patent falsehoods that clog and confuse the Gospel accounts, one still is left with an extraordinary personality to explain. It must be remembered that Jesus was not the only preacher of kindness or worker of mircles that ever had been known among the Jews. Many such men had preceded him; many there were in his own day; and many more came after him. But none other succeeded in so impressing his character on his followers. It took only a little while for his fame to spread throughout Galilee, and soon great crowds came out to see and hear him wherever he went. He was often heckled by the elders in the synagogues, and more than once he was slandered and persecuted. But that only increased his following. We are told that once when he began to preach by the Sea of Galilee, the surging throng on the beach became so heavy that he had to get into a boat and speak from the water! …

But it was only in Galilee that he was then famous, and Galilee was simply a remote and unimportant section of the country. It is probable that in Jerusalem, the capital, not even a rumor of his appearance was yet known. So there came at last the day when Jesus determined to go out from Galilee, and carry his gospel to the rest of his people. He determined to go even as far as Jerusalem and attempt to utter his word in the very stronghold of the priests and rabbis. The time chosen was just before the Passover, for Jesus knew the capital would then be thronged with Jews come from every corner of the land to celebrate the feast in the Temple. So with his twelve chief followers, his disciples, [ p. 269 ] and a little group of women devotees, he courageously set out southward. …

But then came swift tragedy. By the time Jesus reached the capital, his fame had already preceded him. A great mob rushed out to meet him, wildly throwing their cloaks to the ground beneath the feet of the colt on which he rode. They hailed him as their Messiah, as the long-awaited Son of David who would deliver them from their travail. “Hosanna,” they cried ecstatically. “Blessed be he that cometh in the name of the Lord! Hosanna!” . . . One wonders whether those poor wretches out of the alleyways and dunghills of old Jerusalem understood who the man Jesus really was. (One wonders whether even his own disciples understood — or whether even his most pious devotees today understand.) To that frantic mob, at least, he was simply an arch-Zealot, a martial hero who had come to lead them in bloody rebellion against Rome. And when, after three days of teaching in the Temple courts, they discovered that he was nothing of the sort, when they began to see that he [ p. 270 ] wanted them to make peace with God, not war against Rome, they deserted him as quickly as they had flocked to his support. Poor desperate wretches, they were in no mood to seek peace or return good for evil, or turn the other cheek. They did not want to render unto Caesar that which was Caesar’s. They wanted to kill. They wanted to make a holocaust of the whole Roman army, and to become once more a free and prideful nation! . . .

And the moment the populace turned against him, Jesus had no chance. The priests at once began plotting decisive measures against him, for they hated him no less than men of similar kidney had hated every other prophet in Israel. He had scorned them and attacked the whole basis of their cult. Besides, he had publicly flaunted them, storming into the Temple courts one day, and hurling their money-changers out into the street. They dared not let him go on. . . . And although the rabbis despised the priests no less than did Jesus, yet they could not rally to his defense. He had scorned them, too, flaying them for their love of the letter and neglect of the spirit of the Holy Law. He had dared call them hypocrites and whited sepulchres. And, above all, he had outraged them with his unwonted tone of authority. So they, too, were against him.

At the last moment Jesus seems to have realized how reckless he had been in daring to come to Jerusalem. His disciples had warned him against it when they were still safe in Galilee; but young Jesus, in his ardor, had paid no attention. And now he knew himself lost. Belatedly he tried to escape with them, but he was pursued, betrayed, and taken prisoner in a wooded place [ p. 271 ] outside the city walls. He was hurriedly tried by a Jewish court which seems to have been made up largely of priests. Then summarily he was adjudged guilty. From the haste with which the whole trial was conducted, one can judge how terrified were the priests. They seem not to have cared in the least what it was they condemned him for. They were afraid of Jesus, afraid not merely because his heresies endangered their own position, but even more because the excitement which he had aroused among the masses might endanger the peace of the whole land. Rome, the overlord, was wont to put down every sort of public turmoil with scant mercy or patience. So in a panic the elders of the Jews took this young preacher and turned him over to the Roman governor.

And by that governor he was sentenced to die.

There was no justice in it all. How could one expect justice in times so tense and a land so mad? The governor, Pontius Pilate, could have had no understanding of what that young carpenter had done or had dreamed of doing. This Pilate probably thought him but another mad young Zealot, a rebel against Rome, a pretender to the throne of Judea.

And the very next day the life of that young Galilean was snuffed out. The Roman soldiers took him to the top of a hill nearby, scourged him with rods, crowned him in derision with a wreath of thorns, and nailed him to a cross. They nailed him to a cross between two thieves, and over his head they carved the mocking words, “King of the Jews.” And there in mortal anguish he hung for hours. Had he been stronger of body, perhaps life would have lingered in him for days. But [ p. 272 ] had he been stronger in body, no doubt he would never have joined the school of John the Baptist and become a saver of souls. Instead, he would have joined the Zealots, fighting with the sword against Rome, and coming to his end not on a cross but behind some bloodsoaked rampart No, from the beginning his strength must have been not the strength of body but of soul; and toward the end even that strength must have ebbed low in him. For as he hung there on the cross of shame, he was alone, deserted. Gone were the huzzahing crowds; gone even were his own trusted disciples. Only a little knot of desolated women stood by to watch him breathe his last. In the city he was already forgotten. The members of that mob which had so ecstatically received him a few days earlier were now busily preparing for the Passover feast. And his disciples were hiding in the fields, too terrified to confess that they had even known the martyr. So deserted he hung there on that lone hill.

The sun began to set, and the wild violet glow in the west crept up till it lost itself in the blue of the evening sky. The prophet Jesus, his poor body sagging from the bloody spikes that tore his hands and feet, could endure the pangs no longer. He began to moan. Brokenly he moaned as the throes of death came over him. “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?” he begged.

And then he died.

¶ 6

BUT he died only to come to life again, to come to a life more enduring, more wondrously potent than had [ p. 273 ] ever been vouchsafed to him in the days before his shameful death. Indeed, he literally came to life again — according to those who had most earnestly followed him. For ere a week had passed, a revulsion had come over those terrified disciples. In the dread hour of the trial they had fled from their Master; and now their mortification knew no bounds. They trembled at the thought of returning home to Galilee to face the bitter contempt, or worse still, the deathly dejection of their comrades there. Even more, they trembled at the thought of living out the rest of their lives without their Jesus to believe in. That young preacher, with his supernal magnetism, had come to mean too much to them. Without their faith in him and his Messiahship, their own lives became empty, meaningless. Skulking there amid the rock-strewn hills outside Jerusalem, they realized as never before that they still had to believe in him — or die. . . . And, because believing in a corpse was too difficult, they began to believe that Jesus was still alive. They began to say that three days after his burial he had miraculously arisen from the dead. They even declared they had actually seen him in the act of rising from the sepulcher, had seen him as he was taken up to Heaven, right up to the throne of glory. They began to tell how his spirit had actually walked and talked with them, had even broken bread with them! … It was not a desire to deceive that impelled those disciples to tell such stories. They sincerely believed the stories themselves. They were overwhelmingly convinced that Jesus had really come to life again, and was now in Heaven waiting to return once more.

And with this new conviction grown strong in their [ p. 274 ] hearts, the eleven disciples emerged from their hidingplaces and began to preach again. It was not at all a new religion that they began to preach, however. They were still Jews, and they continued to be faithful to the established synagogue and Temple worship. They differed from their fellow Jews only in that they believed that the Messiah had already come, and that He had come in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. They were for that reason called Nazarenes, and probably they formed but one more of many such Messianic sects already in existence. There were the Johannites, who believed John the Baptist had been the Messiah, and who persisted in the belief for yet many generations. There were also the Theudasians, who believed a certain mad preacher named Theudas was the Awaited One, and who clung to the belief until the Romans cut off Theudas’s head. The whole land swarmed with such little sects, for the hunger for salvation in Israel was then as agonizing, and as unsatisfied by the established religion, as it had been, for instance, in India in the day of Buddha and Mahavira.

¶ 7

OF the life of the first Nazarenes we know exceedingly little. It would seem that they dwelt together in little communist colonies, loving each other and sharing each other’s joys and sorrows. They ate at a common table and had no private property. With the noblest ardor they set out to live as their Master had commanded them. . . . And continually, unflaggingly, they sought new members. They went throughout the land, even as far as Damascus, trying to win converts to their little movement.

[ p. 275 ]

But it must have been slow and discouraging labor, for the Messiahship of Jesus was far from easy to prove. Even when the shamefulness of his death could be explained away by a miraculous resurrection, there was still the obscurity of his life to be justified. The Jews had been taught to expect that the Anointed One would be no less than a scion of the royal dynasty of David, an heroic and magnificent prince who would destroy all Israel’s enemies with a mere wave of the hand, and would ascend a throne of gold and ivory and precious stones, to rule then over all the world as the Prince of Peace. It was just the sort of grand and gaudy dream one might expect of a people with a tremendous willto-live cramped in a frail and tortured body. And a village carpenter from half-heathen Galilee, an obscure evangelist who had tramped through the dust to Jerusalem with a tiny following of ragged peasants and reformed sinners, only to be summarily snuffed out by Rome — such a sorry figure hardly measured up to the requirements set down for the hero in that dream. The contrast between the actual Jesus and the imagined Messiah had not been so patent when the preacher had still been alive. The magnitude of his spirit and the fervor of his preaching had been so absorbing as to make men forget altogether whence he had come and how raggedly he was clad. They had been swept away by his simple stirring eloquence, and men had then been quite ready to hail him as the Son of David. . . . But now that Jesus was no longer physically present on earth, all this was changed. To those Jews who had not known him, who had never heard him preach or seen him cast demons out of the mad and the palsied, [ p. 276 ] it was enormously difficult to prove that he had really been the Promised One.

No doubt that was why the disciples began to piece together the genealogies we find in the Gospels. No doubt that, too, was why those extravagant legends concerning the conception, birth, childhood, and ministry of Jesus began to be devised. Uncharitable critics may say the disciples resorted to fraud in these matters — but it was all intensely pious and well-intentioned fraud. Before the ordinary Jew could be made to accept Jesus as the Messiah, Jesus simply had to be proved a descendant of David, whose whole life had been a literal fulfilment of the ancient prophecies. The disciples may not have been even remotely conscious that they were departing from the truth when they solemnly repeated those genealogies and stories. Overzealous disciples never are. . . .

But even with all those new proofs and appealing legends to convince them, the Jewish people as a whole still refused to accept the Messiahship of Jesus. They obstinately kept on awaiting the first coming of the Anointed One, praying for his advent day and night. And the Nazarenes remained obscure, and few in number.