© 1996 Antero Huovinen

© 1996 International Urantia Association (IUA)

| Journal — March 1996 — Content | Journal — March 1996 — Index | Chuck Adjusts His View of the Ultimatons |

Antero Huovinen

Lahti, Finland

It seems to be a common belief among interested readers of The URANTIA Book that Orvonton and the Milky Way galaxy are one and the same thing. In line with this notion, various scientific findings have been suggested as apparently supportive of the information presented in The URANTIA Book as concerns the size and star density of the Orvonton galaxy. Being a regular reader of a number of scientific publications, I know at least something about the recent scientific theories and findings. I keep the scientific methods and the achievements of the sciences in high esteem, but a helpless skeptic as I am, I sometimes fail to believe in what is written in the name of science.

Astronomy is the very sector of basic research where different and divergent theories are suggested more than perhaps within any of the sciences. Even if the methods of observation are the same and the devices more or less identical, the resultant theories are many times divergent, due to the differences in the interpretation of the observations. Many astronomical articles call attention to the uncertainties involved in the various measurings and the difficulties associated with all interpretations based on these findings. Theories are discussed and are submitted to tests using all available means and methods. New methods of observation are introduced from time to time, new devices are deployed, and these methods and devices, along with the new insights of the astronomers, yield ever new theories and revised and updated world outlooks. Maybe even that day will once dawn when the physical systems and patterns explained in The URANTIA Book will be the subject of serious scientific perusal and research.

I shall now present my personal interpretation concerning the size of the Milky Way galaxy, and I refuse to assert that my view would be any truer than that of others.

¶ The Milky Way—Two Connotations

In its original meaning the Milky Way is a phenomenon visible in the nocturnal skies, the luminous belt extending from one extreme of the firmament to the other. Ancient Greeks used to call it galaktos, which is derived from the Greek word for milk, gala. The appellation ‘galaktos’, thus, has nothing to do with a ‘galaxy’ in its modern meaning. Not only in English, but also in some other languages, the Milky Way has a “milky” name: Vía láctea, in Spanish; Voie lactée, in French; Milchstrasse, in German; yet, Vintergatan (Wintry Way) in Swedish, and Linnunrata (Bird’s Trajectory), in Finnish.

The current meaning of the ‘Milky Way’ is a disc-shaped system, consisting in stars, interstellar gas and dust clouds, and commanding a diameter of some 100,000 light-years. The Sun is situated approximately in the mid-section of this disk. I shall hereafter use the word Galaxy in reference to this system. I shall be employing the expression ‘Milky Way’ in its original meaning, the way it is used in The URANTIA Book.

In the mid-18th century, three learned men, Lambert, Wright, and Kant, who viewed the visible phenomenon in the night skies, made the conclusion that the Galaxy is an extremely flattened system of stars. The size of the system was, back then, beyond the reach of any reasonable estimations. Immanuel Kant suggested that the nebulous objects observable in the skies, i.e. the nebulae, are actually other and remote Milky Ways [1]. Only towards the end of the 19th century, the Dutch J. C. Kapteyn, who availed himself of the methods of star-count and observation of star movements, was enabled to determine the diameter of the Galaxy as approximately 50,000 light-years. In Harlow Shapley’s estimation, in the 1920 's, the diameter of the Galaxy was some 300,000 lightyears; the Herbert Curtis estimated diameter of only 30,000 light-years represented the other extreme. This obvious discrepancy in these measurements has continued until recent years. An Encyclopaedia of 1963 suggests that the diameter of the Galaxy be 80,000 light-years, and the distance of the sun from the centre of the Galaxy 27,000 light-years. More recently the solar distance was given as 33,000 light-years, but in the early I980’s the estimation went back to 28,000 lightyears. With regard to such a relatively short distance, the currently deployed devices have reached an exactitude which precludes every doubt as concerns the 100,000 -light-year diameter of the Galaxy. This figure relates to the disc-shaped portion of the Galaxy, where the star density is relatively high in comparison to the outlying regions. Within this disc-shaped section, the orbits of the stars are well-nigh circular. The disk, in modern observations, is surrounded by an ellipsoid halo, which is supposed to extend to a distance of 80,000 light-years from the centre of the Galaxy. The star clusters situated in the region of the halo have elliptical orbits, which means that they belong to a star population different from the stars in the actual Galaxy. The halo is surrounded by a region named the corona, whose extreme limits, as measured from the centre of the Galaxy, are met some 200,000 light-years away. The globular star-clusters belong to the halo which encircles the Milky Way disk. The outer limit of the very thin and extensive corona may be situated at a considerably longer distance, even as far away as 100-300 kiloparsecs [2], from the centre of the Milky Way. [3]

¶ The Milky Way Galaxy Is Not Orvonton

In the words of The URANTIA Book, the Milky Way is composed of star systems and enormous gas clouds which belong to the Orvonton superuniverse. The star systems of our Galaxy are of course visible also in the region of the Milky Way, yet the Galaxy constitutes only a fraction of the superuniverse. The core section of the Milky Way, where the star density is at its highest, is the centre of the superuniverse:

The vast Milky Way starry system represents the central nucleus of Orvonton, being largely beyond the borders of your local universe. UB 15:3.1

From Jerusem, the headquarters of Satania, it is over two hundred thousand light-years to the physical center of the superuniverse of Orvonton, far, far away in the dense diameter of the Milky Way. UB 32:2.11

At 42:5.5 certain sources of radiation are discussed, and in this Paper the densest plane of the superuniverse is unequivocally called the Milky Way:

They emanate in the largest quantities from the densest plane of the superuniverse, the Milky Way, which is also the densest plane of the outer universes. UB 42:5.5

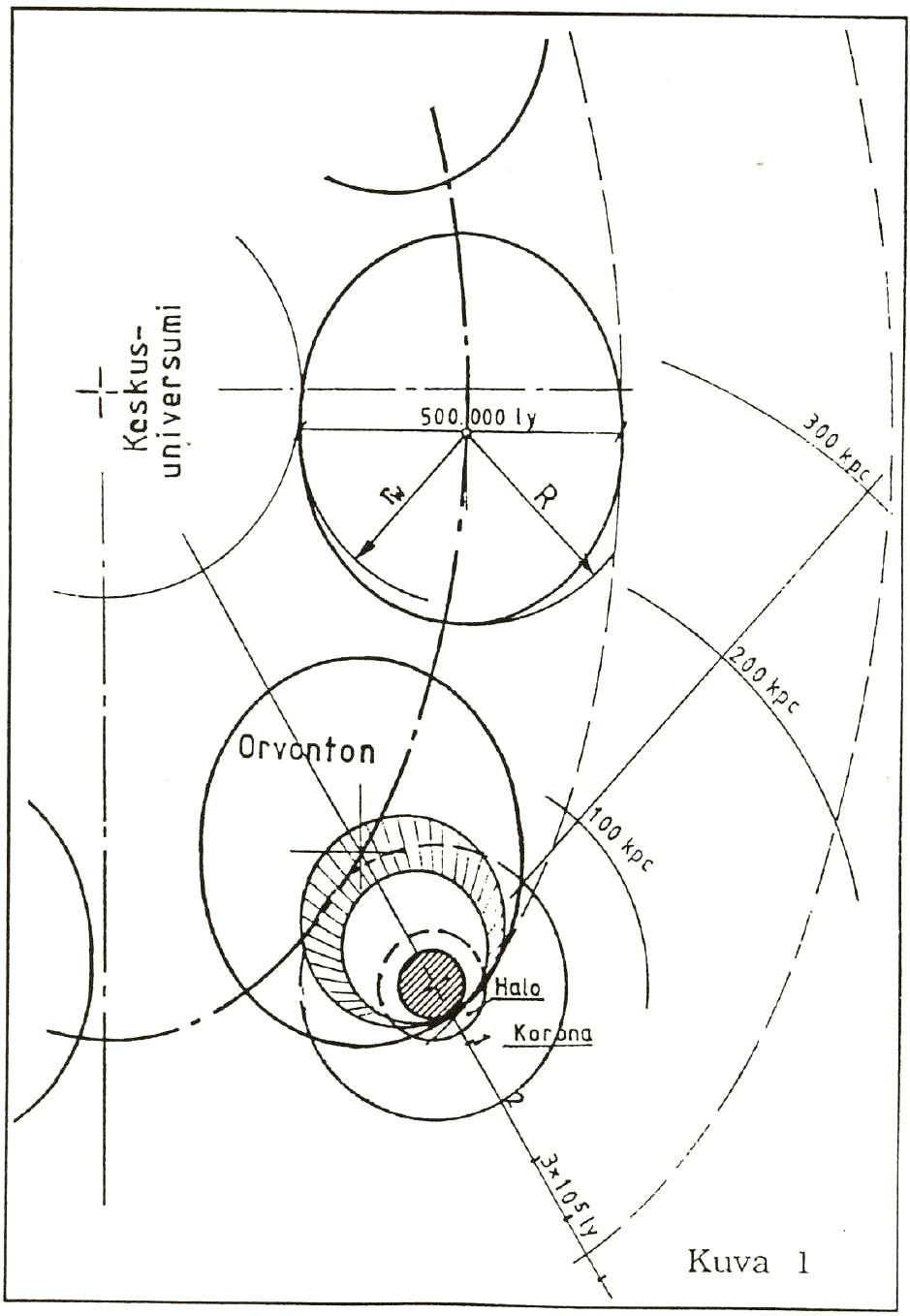

Figure I represents a sketch where the superuniverse is given an elliptical shape, in accordance with the description on 15:3.1 which portrays the horizontal profile of a superuniverse as elongated-circular. In the absence of a more detailed description, I profiled the superuniverse in emulation of the Paradise Isle, which means that the length of the ellipse is one-sixth more than the breadth (cf. UB 11:2.2). In case the breadth is 500,000 light-years, the length has to be 583,333 lightyears. No clearly discernible borders separate the superuniverses, but it may be assumed that a vast majority of the starry systems are situated within a region delineated as an ellipse. In the diagram, the Galaxy is situated in the shaded area, in the border regions of the superuniverse, at a distance of more than 200,000 light-years from the centre of the universe. Neither can the halo and the corona which encircle the Galaxy have any abrupt borders. Their constitution is unknown to us. It can be that a discussion of these belts in some astronomical articles has made some readers mistakenly believe that the size of the Galaxy equals with that of the superuniverse. This view, however, is as erroneous as was the onetime geocentric conception of the universe.

The two eccentric circles in figure I represent a schematic portrayal of the star density of the Milky Way. The Milky Way actually includes all of the Orvonton starry systems, even if not all of them are observable and visible from Earth-a great number of them are situated behind the dense central nucleus.

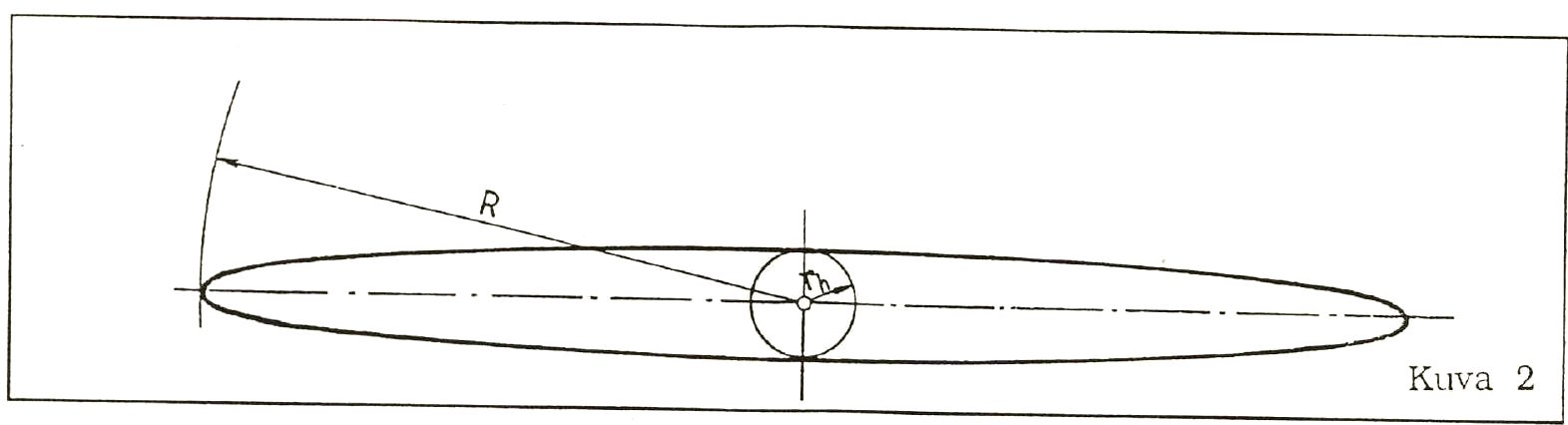

The superuniverse also has a third dimension. In the words of the revealed description, a superuniverse is a watchlike grouping. Let us simplify a little and assume that the side profile of such a watch is an ellipse, and let us once again imitate the pattern of Paradise and postulate its height as one-tenth of its breadth. If we assign the round figure of 151,000 pcs (approx. 493,000 light-years) for the breadth, the length, then, has to be 176,166 pc, and the height, 15,100 pcs.

Figure 2 portrays a side profile of such an ellipsoid. The radius ® of a circle encircling this ellipsoid is 88,083 pc, and that (rw in figure I) of a circle drawn inside the horizontal profile is 75,500 pc, and the radius ( rh ) of a circle drawn inside the lateral profile is 7,550 pcs. Given these values, the volume [4] of the superuniverse is 2.103171124・1014 pc3. The URANTIA Book instructs that the superuniverse of Orvonton will ultimately count with a billion ( 1,000,000,000,000)[5] inhabited spheres, which alone means that the number of stars has to be considerably higher. We may also learn that this space is illuminated and warmed by more than ten trillion [6] blazing suns. UB 15:6.10. If we let the blazing suns in excess of the ten billion (Am. ten trillion) whirl outside the ellipsoid, we may conclude that each star is surrounded by a space of 21.032 pc3; and in reverse, the medium star density would be 0.0475 stars per cubic parsec.

The parable of oranges at UB 41:3.2 lends itself to a calculation of the star density of the universe. The parsec is too massive a unit when it comes to taking the measurements of an orange, so let us avail ourselves of the metric metres instead and then convert the metre readings into cubic parsecs. [7]

The metaphor of oranges instructs us that the stars have just as much comparative elbow room in space as one dozen oranges would have inside a space of the volume of the Earth. At 458:2 the average diameter of suns is given as 1,600,000 kilometres. [8] This figure means that the average volume of a sun is 2.144660585 ⋅ 1027 m3. The volume of the earth is 1.076411815 ⋅ 1021 m3. Star density now depends on the size of the oranges to be used in the computation. But let us assume that an average orange has a radius ( ro ) of 0.04 metres, and consequently, a volume ( Vo ) of 0.00026808 cubic metres. What remains to do is to formulate a mathematical equation and determine the volume (V12) that a sphere needs to command for it to accommodate the twelve average-sized suns of the orange metaphor. A computation reveals [9] that every cubic parsec would contain 0.041 stars. The result is astonishingly close to the figure of 0.047 that we secured above. Using a similar computation, we would discover that had we postulated a 0.042 -metre radius for an orange (instead of the 0.04 above), the star density would be exactly the 0.047 stars per cubic parsec. So, should there be a space with a size of that of the volume of our planet, and should there be twelve oranges with a diameter of 8.4 centimetres, circulating freely within that space, they would have comparatively the same elbow room as ten billion [10] average-sized stars would have in an ellipsoid space with a diameter of approximately 500,000 light-years and modelled after the pattern of the central Isle of Paradise.

¶ Evenly Scattered Stars Or Starry Aggregates?

As a rule, the stars accumulate into aggregations of various shapes and sizes, with an enormous void in between; yet there may be hydrogen clouds in this empty void. Does the allegory of oranges, quoted in The URANTIA Book, denote the average star density within such aggregations, or does it suggest that the stars be more or less evenly dispersed in the space, with the interstellar distances more or less equal? This question is open to studies based on astronomical observations.

Latest astronomical computations suggest that the average galactic mass is more than 0.2 billion [11] solar masses [12], and that the diameter of a galaxy is some 30 kpc, and its height, one kpc. If we postulate a galaxy of the shape of a cylinder with a 30-kpc diameter and I kpc height, its volume would be 7.069 ⋅ 1011 cubic parsecs, and if we assume further that the star density is the above 0.0475 stars per cubic pc, such a space would accommodate 34,000 million stars.

We may presume that we do not know the true number of galactic stars, but let us assume that 100,000 million stars is a relatively correct figure. That would yield 7.069 cubic parsecs as the average volume to accommodate one star and give a star density of 0.1415 stars / pc3. The comparison with oranges gave a result of 0.0475 stars / pc3, in case the stars are dispersed evenly in the space. Evidently they are not evenly dispersed, but instead form aggregations. If the star density within such aggregations, or star accumulations, is the above 0.1415 stars per cubic parsec, we have to conclude that the volume occupied by starry aggregations takes about one third of the total galactic volume, and that about two thirds of the total volume is free from stars.

Simple calculations like these, of course, have nothing to do with astronomy proper; all they can achieve is to give a summary conception of the relative distances between stars and star aggregations.

The Milky Way Mass > 2 ⋅ 1011 times the solar mass Diameter of the disc 30 kpc Thickness of the disc 1 kpc Diameter of the halo 50kpc Sun’s distance from the Milky Way centre 10 kpc Sun’s orbital velocity around the centre 220 kilometres/second

| Journal — March 1996 — Content | Journal — March 1996 — Index | Chuck Adjusts His View of the Ultimatons |

¶ Notes

Kosmos, maailman muuttuva kuva, p. 248, Publications of Ursa, 1990 ↩︎

One kiloparsec, kpc, equals 3.262 light-years ↩︎

Fundamental Astronomy, p. 407, Publications of Ursa, 1984 ↩︎

Vsu = (4 π / 3) Rrwrh = 2.103171124 ⋅ 1014 pc3. ↩︎

American trillion ↩︎

British ten billion ↩︎

A parsec is the length of the hypotenuse in a right-angled triangle whose sharp corner is one arc second and the opposite shorter side is the distance between the Earth and the Sun. This distance is also one ‘astronomical unit’, AU. One AU is 1.4959787 ⋅ 1011 metres, which means that one parsec AU / sin(1 / 3600) = 3,0856777567 ⋅ 1016 metres. This figure in its third power gives the metric value of a cubic parsec, 1 pc3 = 2.937998905 ⋅ 1049 cubic metres. One light-year (ly) is the distance that light travels in a year; in other words it is one year (given as 31,557,600 seconds) multiplied by the speed of light (metres/second): 3.15576 ⋅ 10^{7} ⋅ 2.997925 ⋅ 108 = 9.460731798 ⋅ 107+8 = 9,460731798 ⋅ 1015 metres. ↩︎

Consequently the radius ( rs ) of our Sun is 8 ⋅ 108 metres, and its volume ( Vs ) is 2.144660585 ⋅ 1027 cubic metres. The radius of the Earth ( ru ) is 6.35765 ⋅ 106 metres, and consequently, its volume (Vu) = 1.076411815 ⋅ 1021 cubic metres. ↩︎

Vo/Vu = Vs/V12 ⇔ V12 = VuVs/Vo; V12 = 8.611216555 ⋅ 105 cubic metres/twelve stars; which in cubic parsecs is 293.098 pc3 / 12 stars. Thus, the space accorded to one star is 24.245 pc3, and thus 0.041 stars per cubic parsec. ↩︎

American ten trillion. ↩︎

American, 200 billion ↩︎

The mass of the Sun is 1.989 ⋅ 1030 kg ↩︎