© 1992 Merlyn H. Cox

© 1992 The Christian Fellowship of Students of The Urantia Book

| The Cultural Impact of The Urantia Book in the Next Fifty Years | Spring 1992 — Index | Some Quotations from The Urantia Book |

The “Holy Land” has always held a special interest and even fascination for Christians. Pilgrims have long journeyed there to be near the places where the events of the Old and New Testament took place. It is more than a matter of satisfying academic curiosity. For Christians as well as for Jews, traveling to Israel is a kind of spiritual homecoming. People wish to “walk where Jesus walked”, to visit the towns and areas where he lived and taught, to look out over the landscape and see the same hills and valleys and the shimmering waters of the Sea of Galilee.

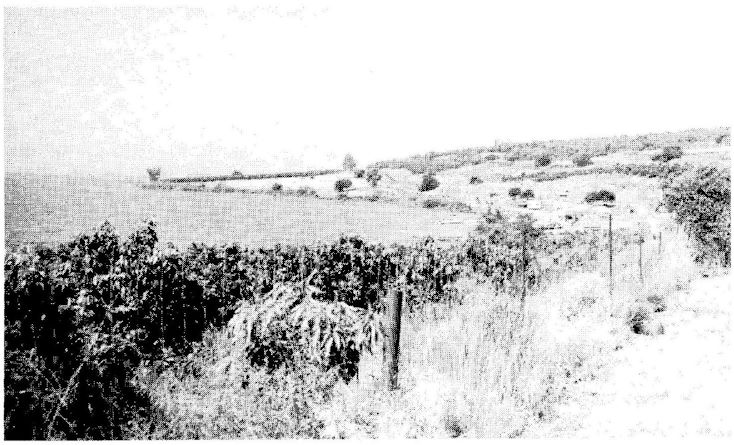

Most are not disappointed. While the dream of returning to sites as they were 2,000 years ago must give way to the realistic expectation of change, it is surprising in how many places so little has changed. So while Caesar’s Hotel rises up along the coast linc of Tiberius, now a popular tourist resont on the Sea of Galilee, you can walk north along the shore road, past Magdala, Mt. Arbel, across the plains of Tabgha, the ruins of Capernaum and down to Kursi, and see the landscape very much as the disciples would have seen it 2,000 years ago.

If you get off the beaten path, you can easily get the feeling that there are many places little touched by time. Bedouin shepherds living in tents still tend their sheep and goats in the Judean wilderness, using the same wells their ancestors have used for thousands of years.

However, our knowledge about where many events took place is still uncertain, and much of that has come from the past two centuries of archaeology, rather than from any clear and unbroken tradition reaching back to those events. Following the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 A.D., Jews and early Christians (being mostly Jewish converts) were driven out of Jerusalem and even denied entry under penalty of death. Generations passed before they were back in the city in significant numbers.

Important early Christian communities formed outside of Palestine due to the work of Paul and the other apostles and disciples. The gospels themselves were written outside of Palestine, which may account in some measure for their lack of specific detail concerning the places where recorded events took place. The process of this isolation of newly formed Christian communities was well under way. In fact, there is no clear and definite proof of any Christian community in the Holy Land from about 70 to 270 A.D., although there is evidence of a Christian presence during this period. [1]

A great resurgence of interest in locating the “holy places” took place during the reign of Constantine in the fourth century. Many great churches and monuments were built during this period on sites then believed to be authentic, although the evidence in some cases is quite suspect.

After the fall of the area to Islam, travel and contact again became difficult and dangerous. During the dark ages of Europe contact with Palestine was minimal, with only a trickle of pilgrims bringing back stories and information about the Holy Land. The Crusades brought renewed interest. but their failure also brought another lapse in safe access to the holy sites.

It is not surprising then that most of our knowledge of Palestine has come from archaeological work in the past two centuries. One could make the case that serious archaeological study of the near east began when Napoleon led a French military expedition to Egypt in 1798 and one to Palestine the following year. He brought with him a group of scholars who made a careful study of the ancient remains. Another great resurgence of interest followed their publication. British and German adventurers and scholars soon followed, bringing back fascinating artifacts, drawings and stories of the native people.

Modern stratigraphical techniques began near the end of the nineteenth century, and improved techniques and methodology have increasingly made archaeological work more accurate and revealing. Clearly, most of our knowledge of Palestine has come during the past 100 years.

Modern stratigraphical techniques began near the end of the nineteenth century, and improved techniques and methodology have increasingly made archaeological work more accurate and revealing. Clearly, most of our knowledge of Palestine has come during the past 100 years.

To get an idea of how recent much of our knowledge is, we have only to consider that until the 1930’s, we were still uncertain of the location of Capernaum. Capernaum was Jesus’ home during his adult life, and the town, next to Jerusalem. most often mentioned in the New Testament. While some excavations at this site took place as far back as the mid 1800 's, its identification remained open to question. and it remained largely buried under rubble until the Franciscans purchased the land from local Arabs in the 1894. Since then a great deal of work has taken place, including the reconstruction of an ancient synagogue. Though the synagogue dates to the 4th or 5 th centuries, there is evidence to suggest it was built on the foundation of an earlier synagogue dating to New Testament times. Since the late 1960 's convincing evidence been also been found to indicate the location of Peter’s home close by, a site used by early Christians as a home-church, and still later as a destination for pilgrims.

¶ Palestine in New Testament Times: In General

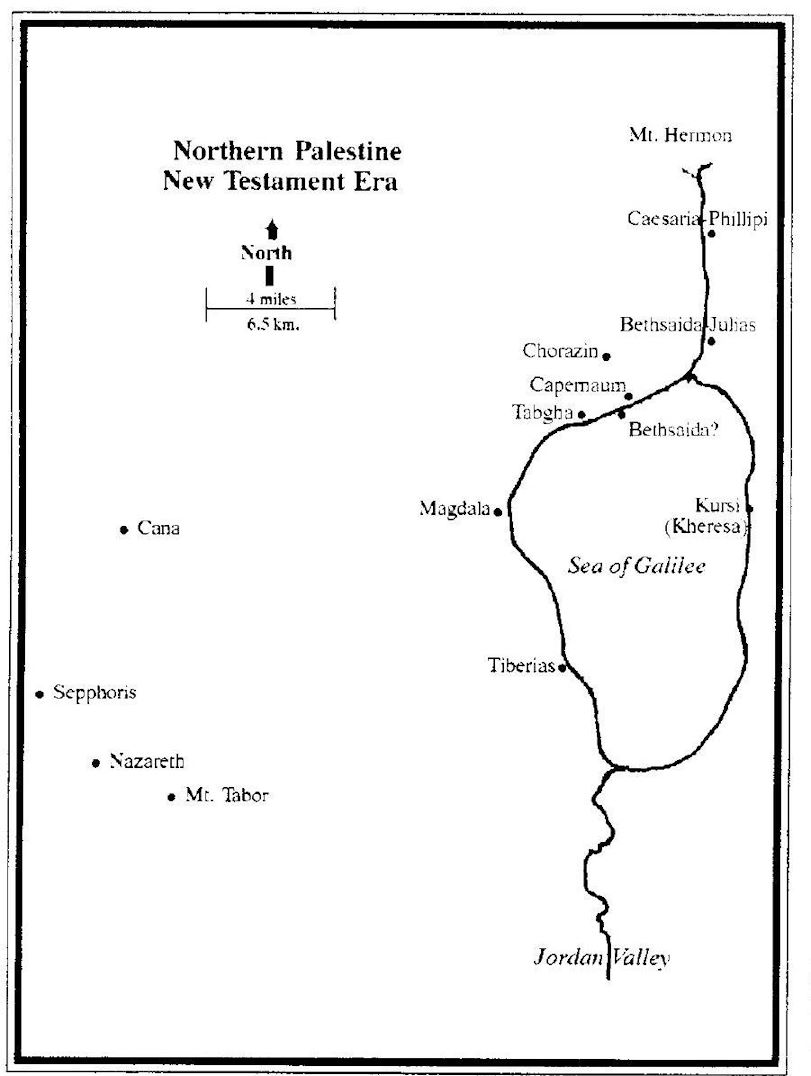

Our knowledge of Palestine and the area around the Sea of Galilee in New Testament times is therefore still quite incomplete. Much of our knowledge comes from the records of the Jewish historian Josephus, either directly or by inference; but again, much has come from archaeology. Some 134 settlements in the area of the Golan (northeast Palestine adjoining Galilee) are on the Israeli antiquities survey. Five of these are large enough to be considered cities, fourteen provincial towns, twenty eight large villages, and eighty seven small hamlets or agricultural settlements. Fifty one other sites cannot yet be accurately assessed. The survey necessarily reflects a significant population growth in this area from 135 AD through the fourth century. [2] The region of Galilee in New Testament times is considered to have had as many as nine towns in excess of 15,000 population, large communities by Biblical standards.

We know that major trade routes crossed through upper Galilee and the city of Sepphoris on the way to Damascus. Sepphoris was rebuilt by Herod Antipas as the capital of Galilee, and in Jesus day it was the second largest city in Palestine. Josephus referred to it as the “ornament of all Galilee.” Following the fall of Jerusalem, it was for a time the seat of the Sanhedrin, the governing body of the Jews. The Mishnah, a compilation of the oral tradition, was completed there in the third century.

According to tradition, it was also the birthplace of Mary and her parents, Joachim and Anna. Although Sepphoris is not mentioned in the New Testament, it lies only about 4 miles northwest of Nazareth. One can climb the north ridge in Nazareth and still see the winding trail leading to the city’s remains, within easy walking distance.

In contrast to the lack of specifics in the New Testament concerning the geography of events in Jesus life, The Urantia Book is rich in such detail.

What Nazareth was like in Jesus’ day also remains unclear. Some believe that it was a small hamlet populated by a few extended families. A recently excavated cave beneath the Church of the Annunciation is thought by some to be representative of the kind of primitive dwelling Joseph and Mary and their family may have lived in.

¶ New Testament Palestine in The Urantia Book

In contrast to the lack of specifics in the New Testament concerning the geography of events in Jesus life, The Urantia Book is rich in such detail. For example, Jesus’ journey from Beersheba to Dan before the beginning of his public ministry is described as follows: “On this journey northward he stopped at Hebron, Bethlehem (where he saw his birthplace), Jerusalem (he did not visit Bethany), Beeroth, Lebonah, Sychar, Schechem, Samaria, Geba, En-Gannim, Endor, Madon; passing through Magdala and Capernaum he journeyed on north; and passing east of the Waters of Meron, he went by Karahta to Dan, or Caesarea-Philippi.” (UB 134:7.5)

On another occasion Jesus and the disciples, traveling from Caesarea-Philippi to the Phoenician coast, “passed around the marsh country, by way of Luz, to the point of junction with the Magdala-Mount Lebanon trail road, thence to the crossing with the road leading to Sidon, arriving there Friday afternoon.” (UB 155:4.1)

During the Perean mission, they “worked in the following cities and towns, and some fifty additional villages: Zaphon, Gadara, Macad, Arbela, Ramath, Edrei, Bosora, Caspin, Mispeh, Gerasa, Ragaba, Succoth, Amathus, Adam, Penuel, Capitolias, Dion, Hatita, Gadda, Philadephia, Jogbehah, Gilead, Beth-Nimrah, Tyrus, Elealah, Livias, Heshbon, Callirrhoe, Beth-Peor, Shittim, Sibmah, Medeba, Beth-Meon, Areopolis, and Aroer.” (UB 165:0.1)

There are references to over one hundred and twenty five towns and villages in these narrations. It describes Galilee as “a province of agricultural villages and thriving industrial cities, containing more than two hundred towns of over five thousand population and thirty of over fifteen thousand.” (UB 124:2.9)

As regards the town of Nazareth, “From time immemorial, many caravan routes from the Orient passed through some part of this region to the few good seaports of the eastern end of the Mediterranean, whence ships carried their cargoes to all the maritime Occident. And more than half of this caravan traffic passed through or near the little town of Nazareth in Galilee.” (UB 121:2.2)

Nazareth was a caravan way station and crossroads of travel. Joseph’s primary means of supporting his young family was in running a small workshop near the caravan lot. Here Jesus as a young lad could listen in on the conversations of conductors and passengers from the all over the known world.

Galilee is described as largely gentile in population; in fact. in Jesus’ day it was more gentile than Jewish. The Jews of Nazareth are also described as being more liberal than most in their interpretation of social restrictions based on the fear of contamination by contact with the gentiles, thus giving rise to the common saying in Jerusalem, “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?”

There are also many references to the city of Sepphoris. Jesus frequently visited there as a child, and as a adult spent several months working there as a smith. Sepphoris was also the place where Joseph met a tragic death. When Jesus was but fourteen, Joseph was a foreman on the construction of the governor’s residence and was critically injured by a falling derrick.

¶ Specific Issues: The Location of Bethsaida

The straightforward description of the locations of events is sometimes at odds with tradition. For example, the transfiguration, according to The Urantia Book, took place on the gentile mountain of Mt. Hermon, not on the traditional site of Mt. Tabor. This is, however, in keeping with scholarly evidence that has long recognized that Mt. Tabor would have been an unlikely spot since it was topped by an armed garrison at the time. But tradition, once set, often overrides all other reasonable evidence.

Another issue of more current and scholarly interest involves the location of the town of Bethsaida. Next to Jerusalem and Capernaum, it is the town most mentioned in the gospels. It is the birthplace of Peter and Andrew and the home of the apostle Philip. It has been traditionally considered the home of the fisherman Zebedee and his sons, James and John. Many events recorded in the gospels took place near there, including the healing of the blind man and the second feeding of the multitude.

There is still considerably uncertainty, however, about just where it was located. Many scholars now identify it with the town of Bethsaida-Julias, a town raised by Herod’s son Philip, and named in honor of Philip’s daughter Julia. The difficulty with this assumption, however, is that John specifically locates Bethsaida in Galilee, not in Philip’s domain of Gaulinitis, where Bethsaida-Julias is located. [3] The Jordan River was the boundary between the two regions. The argument has been offered for an alternative location further south, bordering on the Sea of Galilee, where the town may have spread out over both sides of the river.

There seems to be no way to settle the issue on the basis of current evidence. The Urantia Book, however, gives an alternative picture, one in keeping with John’s record. Here it is quite clear that Bethsaida and Bethsaida-Julias were two different towns some distance apart.

Bethsaida is described as the “fishing harbor of Capernaum.” It was located on the sea of Galilee “just down the shore” from “near-by” Capernaum; so close that one gets the impression that Bethsaida was a virtual suburb of Capernaum. It one instance it is even referred to as “Bethsaida in Capernaum.”

Bethsaida is described as the “fishing harbor of Capernaum.” It was located on the sea of Galilee “just down the shore” from “near-by” Capernaum; so close that one gets the impression that Bethsaida was a virtual suburb of Capernaum.

Most traditional accounts, however, such as that of Theodosius in the sixth century, clearly state or suggest that these towns were several miles apart. [4] As to where the location of these towns were thought to be when so identified is not always clear, but current consensus is that Peter’s home and the synagogue of Capernaum were very close to each other.

According to The Urantia Book, Bethsaida was indeed the home of Zebedee and his two sons, James and John, and the home Jesus resided in while working in the Zebedee boat shop. Peter’s home was also in Bethsaida and near that of Zebedee, and the disciples often stopped by the home of Peter on the way to and from the near-by synagogue (Capernaum). On one occasion, as Mark’s recounts. “As soon as they left the synagogue, they entered the house of Simon and Andrew…” [5]

In the Gospel of Mark, Peter is said to have lived at Capernaum, while John says that Bethsaida was the “city of Andrew and Peter.” If Bethsaida was not only the birth place of Peter, but also his home as an adult, and these towns were so close together, this could explain some confusion in the records.

According to The Urantia Book narratives, the Zebedee home became the headquarters for the disciples and homebase for their missionary and evangelistic outreach. The great event of multiplc healings took place in the front yard of the Zebedee home the same evening of Jesus’ ministry to Peter’s mother-in-law. And it was at the Zebedec home that the paralytic, “carried down from Capernaum on a small couch by his friends,” was lowered inside from the root. (UB 148:9.2) Al one time Bethsaida was the location of a large seaside tent city made up of various seekers and followers, and included a training school for new disciples, as well as a sizeable hospital.

It is also interesting to note that, according to The Urantia Book, it was Bethsaida-Julias, not Bethsaida, which was listed among those cities so unresponsive to the proclamation of the good news: “Woe to you, the inhabitants of Chorazin, Bethsaida-Julias, and Capernaum, the cities which did not receive well these messengers. I declare that, if the mighty works done in these places had been done in Tyre and Sidon, the people of these so-called heathen cities would have long since repented in sackcloth and ashes.” (UB 163:6.5)

In retrospect, one might question the gospels’ account for this reason: why would Jesus have mentioned Bethsaida, when it was, in fact, so clearly productive of disciples and followers?

¶ Using The Urantia Book as a Source for the “Geography of Faith”

Will we ever be able to verify or disprove such a picture, especially in regards to such specific questions as the location of Bethsaida? It is difficult to say. While it would appear very difficult for archacology to confirm or deny with certainty, I would hesitate to place limits on what future work might reveal. A combination of new historical insights and archaeological investigations may lead to convincing new evidence, or the always hoped for but elusive “proof.” The reasonableness of The Urantia Book position, it seems to me, ought at least to stimulate those interested to test it further.

This is but a brief overview of how The Urantia Book can be used as a source to interact with ongoing scholarly research, as well as to enrich our knowledge and understanding of the events in Jesus’ life. I believe those persons, lay or scholar, who are interested in the “geography of faith” will find The Urantia Book a stimulating and immensely satisfying resource. The authors, while clearly eschewing any overly sentimental attachments to supposed holy sites, do seem to appreciate the natural curiosity and human sentiment attached to such places. These authoritative and graceful narratives give us not only a comprehensive understanding of Jesus ’ life and teachings, but a richly detailed geographical backdrop against which this greatest of all divine-human events took place.

The author traveled extensively in Israel and briefly in Egypt during the summer of 1989. In addition he participated for two weeks as a volunteer at an archaeological dig in Sephorris, a project jointly sponsored by the American Schools of Oriental Research, Duke University, and the Israeli Department of Antiquities.

| The Cultural Impact of The Urantia Book in the Next Fifty Years | Spring 1992 — Index | Some Quotations from The Urantia Book |

¶ Notes

Eric Myers, “Early Judaism and Christianity in the Light of Archaeology,” Biblical Archaeologist, June, 1988, p. 69. ↩︎

Ibid, p. 76. ↩︎

Modern scholarship and The Urantia Book both place Bethsaida-Julias south of Caesarea-Philippi. According to The Urantia Book Bethsaida-Julias was located south of Caesarea-Philippi and north of Magadan park, an area on the eastern shore of Galilee frequently visited by Jesus and the disciples. The park was one of several located north of Kursi, (or Kheresa in The Urantia Book-see map), “near” and “just south of Bethsaida-Julias.” ↩︎

Bargil Pixner, “Searching for the New Testament Site of Bethsaida,” Biblical Archaeologist, December, 1985, p. 208. ↩︎

Mark 1: 29, N.R.S.V. ↩︎