© 2009 Jan Herca (license Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0)

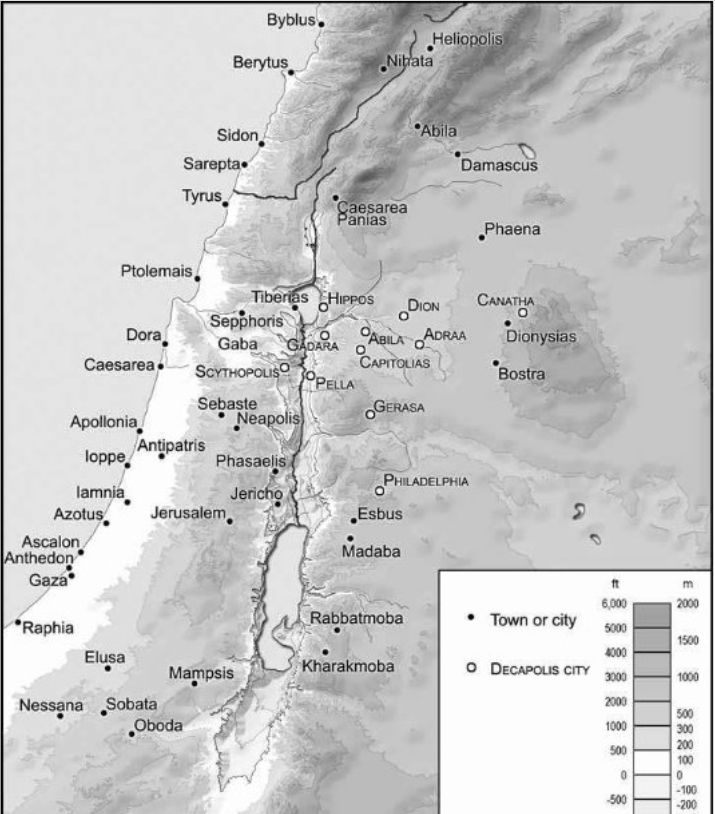

The Decapolis consisted of a group of a few cities (about ten, hence its name) that originated during the Hellenic influence of the 2nd century BC. It was not properly a territory of Palestine, like Judea and Galilee, but the area it comprised was approximate and did not have a defined territorial demarcation.

Most of the cities, as we have said, were formed when the descendants of Alexander’s generals, the Lagids of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria, conquered Palestine. It included these ten towns: Scythopolis, Pella, Gerasa, Philadelphia, Hippos, Gadara, Abila, Dium, Rafana and Damascus. The most notable were Gerasa, Pella, Hippos, Gadara, Philadelphia and, further north, Damascus.

All were in the transjordan, except Scythopolis, which was the only one on the west side of the Jordan. They comprised a somewhat indefinite area, as we have said, surrounding Perea to the north and east.

¶ History

Pompey had granted them municipal autonomy, always under the government and sovereignty of Rome. The Maccabees fought to return these cities to Judaism, but their success was relative. Alexander Jannaeus himself had to face the obvious: the Decapolis, despite being embedded in the territories of Israel, was a world apart, clearly Hellenized, dominated by trade, culture, and the Greek gods. The case of Pella, for example, was dramatic. He preferred its destruction to falling under the control of Jerusalem. Herod the Great, more astute than the Maccabees, reached a pact with the Decapolis, benefiting from its undoubted progress.

It must be said that these were not the only Hellenized cities in Israelite territory. Over time, other cities, such as Ptolemais (ancient Acca or Acre), Gaza, and Caesarea (the great port of Israel), also ended up entering the Greek sphere. Shechem was also rebuilt by Herod, receiving the name Sebaste and housing a significant Greek population. The same would happen with Tiberias and Sepphoris, the capital of Galilee. The Romans, upon seizing power in Palestine after Herod’s death, contributed to the estrangement and suspicion between the Jews and the inhabitants of these cities, establishing military garrisons there, with significant auxiliary troops of Samaritan origin.

Consequently, the general feeling toward these cities was one of caution. If they could be avoided, one would not even go near them. For the Puritan inhabitants of Judea, contact with these foreign populations impure their persona. However, these exaggerations did not apply to the more open-minded people of the rest of the regions of Palestine.

¶ Philadelphia

Philadelphia was located towards the south of the Decapolis region. Today this city is known as Amman, the capital of Jordan.

.png)

¶ History

Excavations inside and outside the present-day city of Amman have revealed finds as early as 3500 BC. Occupation of the city, called Rabbath Ammon in the Old Testament, has been continuous, and artifacts found in a Bronze Age tomb show that the ancient city engaged in extensive trade with Greece, Syria, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia.

Biblical references are numerous and reveal that, around 1200 BC, Rabbath Ammon was the capital of the Ammonites. During the reign of King David, he sent Joab ahead of the Israelite armies to lay siege to Rabbath, after having been insulted by the Ammonite king Nahash.

David seems not to have been the most benevolent of monarchs. After taking Rabbath, he burned its inhabitants alive in a brick kiln and, before taking the city, sent Uriah the Hittite “to the forefront of the fiercest battle,” where he would die, simply because David had become infatuated with Uriah’s wife, Bathsheba.

The city continued to prosper and supplied David with weapons for his ongoing wars. His successor, Solomon, erected a temple in Jerusalem to the Ammonite god Molech. From this point on, the only biblical references to Rabbath are prophecies of its destruction at the hands of the Babylonians, who did in fact capture the city but did not destroy it.

The history of Amman from then (c. 585 BC) until the time of the Ptolemies of Egypt is unclear. Ptolemy Philadelphus (283–246 BC) rebuilt the city during his reign and named it Philadelphia after himself. The Ptolemaic dynasty was followed in turn by the Seleucids and, briefly, by the Nabataeans, before Amman was captured by Herod around 30 BC and thus fell to the Romans. The city, which even before Herod’s arrival had felt Roman influence as a member of the semi-autonomous Decapolis, was completely replanned and rebuilt in a typically grandiose Roman style.

¶ Description

In Jesus’ time, we have to imagine Philadelphia as a Roman city in its full splendor. The citadel stood on a hill that, along with five other hills, formed a circle. Between these hills, to the south of the citadel, a river crossed the present-day Wadi Abdoun.

The Roman theater was impressive. It was excavated into the northern slope of a hill that had once served as a necropolis. In the 2nd century AD, another theater was built on top of the existing one, seating 6,000; the one from Jesus’ time was somewhat more modest. It served not only the entertainment function of a theater, but also a religious function, as the upper row of seats housed a statue of the goddess Athena, of particular importance to the city.

Directly in front of the theater are the remains of a colonnaded plaza that once formed part of the city forum.

To the east of what was once the forum is the Odeon, which, although built at the same time as the Roman theater, already existed in the same area at the time of Jesus. It served primarily for musical performances. The seats faced west. It was protected by a temporary cloth roof during performances to protect the musicians and the audience from the elements.

The Nymphaeum was to the west of the theater; it had a beautifully decorative facade.

Within the citadel walls, on the hill, were several palaces (nothing remains of them today, this is assumed). To the south was a temple dedicated to Hercules (the present ruin is part of a reconstruction by Marcus Aurelius). On the northern slope of the citadel was a huge water cistern carved into the rock.

Presumably, there were public buildings (perhaps baths), a small castle or fortress quartered for Roman troops, temples dedicated to the Greek gods, and a few other buildings under construction at that time.

¶ The Urantia Book

During the journey that Jesus made with his younger brother Simon in 17 AD, for Passover, they met a merchant from Damascus in Philadelphia. He was so charmed by the two brothers that he invited them to his establishment in Jerusalem, where Jesus was able to admire the man’s extensive business throughout the world (UB 128:3.2-3).

It was one of the towns visited by the Twelve, the twelve evangelists, and other women evangelists during their second tour of the Decapolis from August 18 to September 16 A.D. (UB 159:0.2). There Jesus gave a discourse on the positive nature of his religion (UB 159:5.1). It was also one of the towns visited on the Perean mission, from January 3, 30 AD until the death of Jesus (UB 165:0.1).

Jesus and the Twelve were in Philadelphia during their tour of northern Perea from February 11 to 20, 30 C.E. There Abner and his associates had established their headquarters. Jesus arrived in Philadelphia on Wednesday, February 22, followed by over 600 followers, while Peter and Andrew remained in Pella ministering to the crowds. He spent Thursday and Friday resting (UB 167:0.3). On Saturday the 25th, during breakfast, Jesus gave his teaching on what is lawful to do on the Sabbath to an audience of Pharisees (Luke 14:1-6, UB 167:1), explaining his position with the parable of the great supper (Mt 22:1-10; Luke 14:16-24, UB 167:2). That same day, Jesus led the reading in the synagogue services and then healed a woman of her depression (Lk 13:10-17, UB 167:3). Two days later, a message arrived in Philadelphia from Bethany: Lazarus was very sick.

Jesus’ tenth postmortem morontia appearance took place shortly after eight o’clock on Tuesday, April 11, 30 C.E., in the Philadelphia synagogue to a group of followers that included Abner, Lazarus, and about 150 of their companions, including some of the evangelists (UB 191:4.1).

The Philadelphia synagogue had never been under the supervision of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem, so Jesus’ teachings endured there longer. A Christian church later stood on the same site as the old synagogue in Philadelphia. Abner was the leader of this church, just as Jesus’ brother James was the leader of the Jerusalem church. There was long-standing enmity between the two churches (UB 166:5.1-3). Abner was supported by Jesus’ friend Lazarus, David Zebedee, and the apostle Nathanael (UB 168:5.3, UB 171:1.5, UB 193:6.4). The church in Philadelphia is the one that remained most faithful to Jesus’ teachings of all the churches that existed (UB 130:2.3, UB 166:5.7). Unfortunately, with the rise of Islam, this church and its area of influence were swept from the face of the Earth (UB 171:1.6) and its teachings were lost.

These latest data provided by The Urantia Book about a fledgling Christian church in Philadelphia are not corroborated by archaeological and historical evidence. No evidence of early Christianity has been found in Philadelphia during the first three centuries AD (see Wikipedia).

¶ References

¶ Scythopolis (Bethsan)

At the foot of the ancient fortress within whose walls the remains of King Saul were displayed, one of the most beautiful Hellenistic cities in Palestine was built, called Scythopolis (City of the Scythians) in the 1st century. The city was undoubtedly named so to recall that the garrison was made up of mercenaries from this people of the steppes. It was dedicated to the Greek god Dionysus, whose nurse, Nysa, was buried on the hill according to a tradition brought back by Pliny the Elder.

¶ History

The Bible identifies Beit She’an as the place where King Saul and his three sons were hanged by the Philistines after the Battle of Gilboa. Despite this, no archaeological evidence has been found of a Philistine occupation of Beit She’an.

In Greek times, the site of Beit She’an was reoccupied under the Greek name Scythopolis. Little is known about the Hellenistic city itself, but during the 3rd century BC a large temple was built on the tell, the hill. It is unknown what deity was worshipped there, but the temple continued to be used through Roman times. Between 301 and 198 BC, the area was under the control of the Ptolemies. In 198 BC, the Seleucids finally conquered the region.

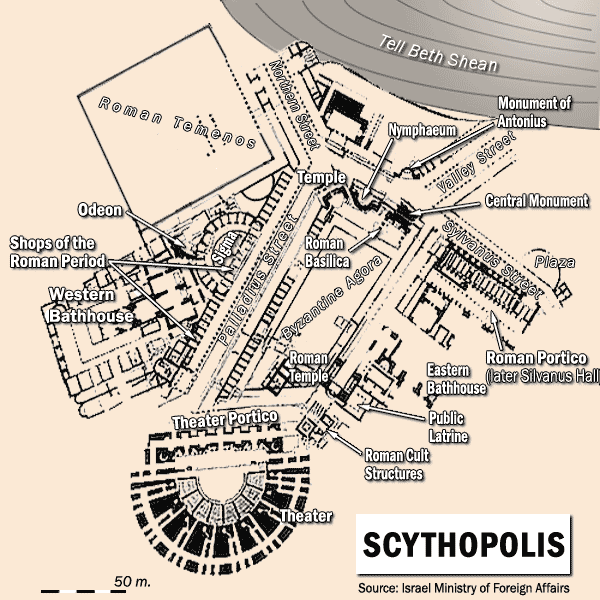

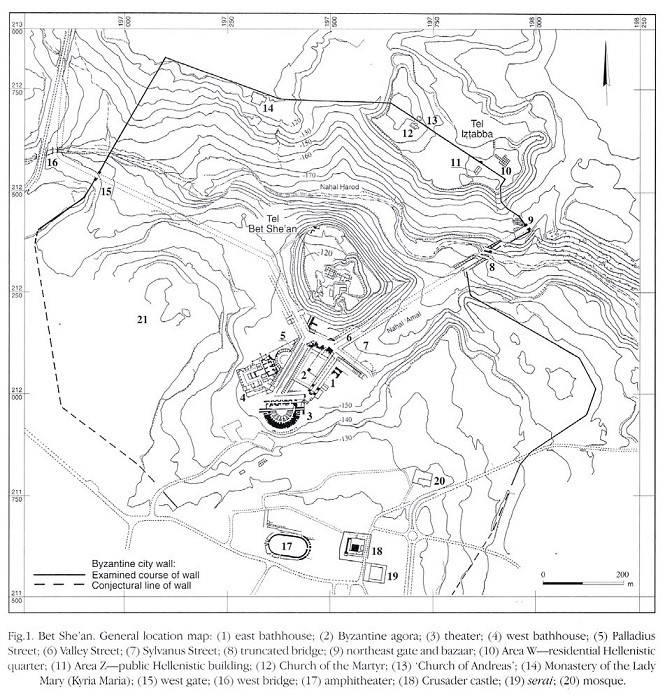

In 63 BC, Pompey incorporated Judea into the Roman Republic. Beit She’an was refounded and rebuilt by Gabinius, sponsored by Pompey. The city center moved from the top of the mound, or tell, to its slopes. Scythopolis prospered and became the principal city of the Decapolis, the only one west of the Jordan River.

The city flourished under the Pax Romana, as evidenced by the urban planning and extensive construction, including a theater, the best preserved to date, although dating from the 2nd century; a hippodrome; a cardo, or colonnaded main street; a basilica; and the Roman odeons, typical of a Roman city with refined urban planning. Mount Gilboa, 7 km away,It provided basalt stone for buildings and water brought in through an aqueduct.

Due to the proximity of the Harod River and a sufficient rainfall regime, Beit Shean was a very fertile area with hundreds of hectares of cultivated fields.

¶ Description

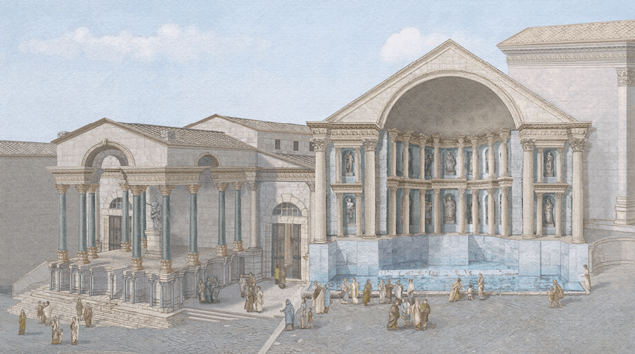

When in the time of Jesus a visitor entered the city through the north-eastern gate, or the gate of Damascus, and rode through the nahal Amal the hill of the ancient Bet she’an, the first one who You will encounter the Nymphaeum, the monumental source, a large decorative source with sculptures and niches, fed by the acuduct. It was a meeting and refreshment point, also a symbol of urban power.

The traveler would enter the cardo of the city, with its majestic columns on both sides and its porticos, where many traders will be available with their doors. Moving forward, the visitor will pass through the area of the Roman Basilica, a large administrative and commercial building. At the coast, the Byzantine Agora (which existed in early Roman times) functioned as a commercial and social centre. On this side there will be a large public plaza covered with porticoes. Here we stand out the Roman Portico (known as the Salón de Silvano), with columns and roofs that overshadow the halls or halls.

In the southernmost part, the visitor will encounter the imposing Roman Theatre, whose facade has the cardo across the Porticus of the Theatre, a monumental columned gallery which announced the access to the spectacles. All this passage unfolds between Corinthian columns, stone floors, statues, fountains, and buildings covered with marble or plaster. The street would be bustling with traders, travellers, locals and visitors from all over the Decápolis. Ultimately, a populous and vibrant city.

¶ The Urantia Book

When Jesus was 11 years old, he accompanied his father to Scythopolis on business. Jesus marveled at the beauty of the city, especially the theater and the pagan temple. He expressed great interest in the athletic games then being held in the amphitheater, which caused great consternation to Joseph and serious anger with his son, a fact that left a lasting impression on young Jesus (UB 124:3.6-8).

Jesus saw the city again, but from a distance, in A.D. 7, when he and his parents first traveled to Jerusalem (UB 124:6.4).

It was one of the sites visited by Jesus, the Jesus Twelve, and the John Twelve during their first preaching tour in the Decapolis in November and December 27 (UB 144:7.1).

It was also visited during the second public preaching tour of Galilee, from Sunday, October 3, to December 30, 28 AD (UB 149:0.1).

Finally, it was one of the towns visited by the twelve, the twelve evangelists, and other female evangelists during the second Decapolis tour from August 18 to September 16, 29 AD (UB 159:0.2).

¶ References

- Wikipedia

- This week in Palestine

- Biblical Archeology Society

- German-Israeli Tell Iẓṭabba Excavation Project

¶ Pella

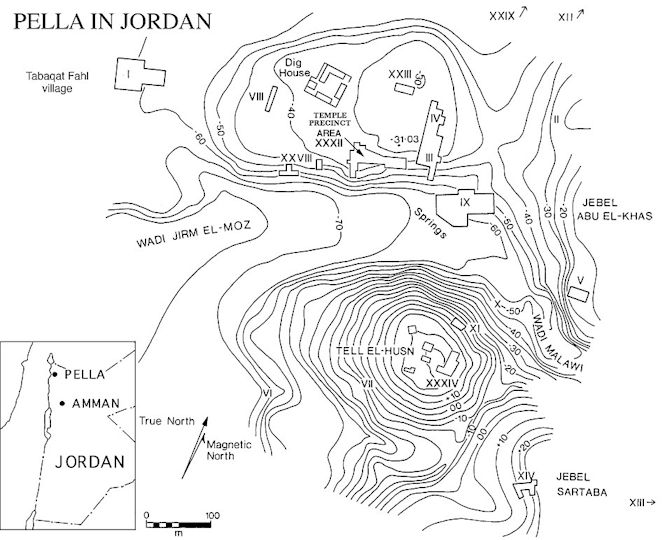

Pella (Greek name) was an ancient city of the Decapolis located in the northwest. It is located near a rich water source in the eastern hills of the Jordan, near a present-day town called Tabaqat Fahl (Arabic name).The current ruins leave little trace of the prosperous city that was in Roman times.

¶ History

Although the site was inhabited as early as 5000 BC, and Egyptian texts make several references to it in the second millennium BC, it was during the Greco-Roman period that Pella flourished. The city’s original name, Pehel, appears to have been changed to that of the birthplace of Alexander the Great. Pella followed the fate of many other cities in the area, which came under the control of the Ptolemies, the Seleucids, and the Jews, who largely destroyed Pella in 83 BC because its inhabitants showed no inclination to adopt the customs of their conquerors. For a time, it was named Berenike and Philippeia, surely in honor of illustrious patronesses, but it soon reverted to its original name of Pella.

Pella was one of the important cities of the Decapolis. During the first century AD, it was a flourishing place with a good cosmopolitan population of Gentiles and Jews. It was one of the eleven administrative districts (or toparchies) in Roman Judea. During the outbreak of the First Jewish-Roman War (66-74 AD), when the Syrian inhabitants of Caesarea murdered its Jewish citizens, there was a general Jewish uprising against the neighboring Syrian villages, seeking revenge, and Pella was sacked and destroyed.

In what is known as the “flight to Pella,” somewhat before the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, one tradition holds that a group of Nazarite Jewish Christians took refuge in Pella, making this city a Christian center. According to Epiphanius, Jesus had advised the disciples to leave Jerusalem before it was besieged. The Urantia Book shows us in one passage that this did indeed happen (UB 176:1.4-5): “…the entire group of believers and disciples fled from Jerusalem as soon as the Roman troops appeared, finding a safe refuge north of Pella.” And it also mentions one of those Jewish Christians who found refuge there (UB 121:8.7): “Isador [a disciple of the apostle Matthew] fled from Jerusalem in 70, after the city was blockaded by the armies of Titus, and took a copy of Matthew’s notes to Pella. In 71, while living in Pella, Isador wrote the Gospel according to Matthew. He also possessed the first four-fifths of Mark’s account.”

¶ Description

The city was walled from ancient times, with a main mound around which the ancient city was laid out. The more modern area had extended over a wadi (today called Al-Jirm).

It had a theater or Odeon in this wadi, a Roman Nympheum or baths, and, ultimately, the typical public buildings for the Roman officials who lived there.

The proximity of the Jordan River made this city a vital center on the Jewish route across the Jordan. Irrigated crops made the city a place of great wealth.

¶ The Urantia Book

Jesus and his brother Simon passed near Pella on their journey to Jerusalem for Passover in 17 AD

When John the Baptist arrived at the ford of the Jordan River near Pella in January 26, it marked the time when Jesus decided to enter into public activity, finally leaving his work as a carpenter and boatbuilder (UB 134:9.8). On Sunday, January 13, Jesus appeared before his cousin at the ford, requesting to be baptized (UB 135:8.3). After the baptism, Jesus withdrew to the hills east of Pella (UB 136:4.14). He returned to Pella on Sabbath, February 23, 26, where he was reunited with John and his disciples and nursed an injured boy. (UB 137:0.1)

Jesus and the twelve passed near Pella on their way to Jerusalem on the 27th to celebrate the Passover. (UB 141:1.2) After the first preaching tour in the Decapolis, in November and December 27, Jesus established his headquarters at Pella (UB 144:8.1). There they received news of the death of John the Baptist.

After sending the 70 evangelists on their mission, Jesus returned to Pella as his headquarters on December 6, 29 A.D. (UB 163:5.1, UB 163:6.1). During the Perean mission, from January 3, 30 A.D. until Jesus’ death, Pella was the center of operations, where the multitudes were received and where Jesus taught, whether or not a couple of apostles were present (UB 165:1). During this time, while the disciples were carrying out their mission in Perea, Jesus delivered many notable teachings at Pella, such as the sermon on the Good Shepherd (UB 165:2), the sermon on not being afraid (UB 165:3), the sermon on covetousness and the division of inheritances (UB 165:4), the sermon on wealth (UB 165:5), and others (UB 165:6). The Pella camp was definitively broken on March 13, 30 (UB 171:1.1).

¶ References

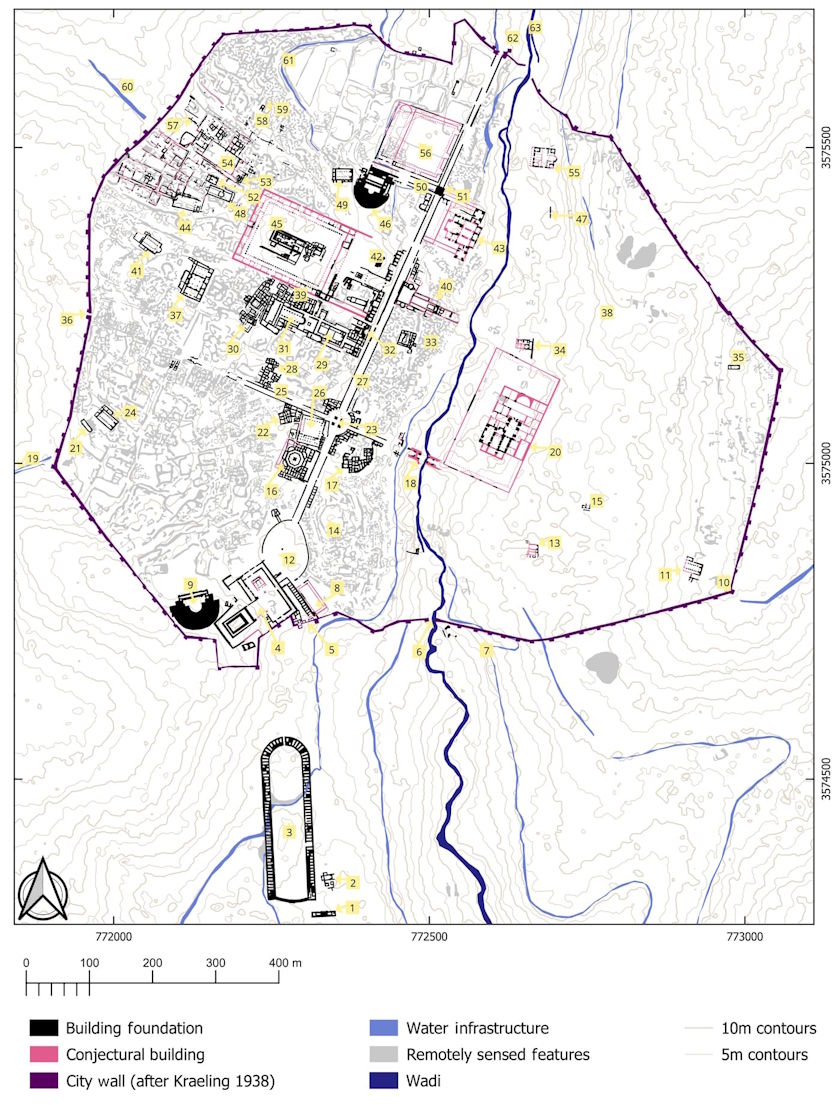

¶ Gerasa

The city is a marvel of conservation due to the quality of its preserved ruins. It is located in the hills of Gilead. Today it is called Jerash.

This modern city stands on the eastern bank of a small tributary of the Zarqa River, while the ancient city was on the western bank.

It is estimated that at its peak, Jerash could have housed a population of around 15,000 (which gives a good idea of its prosperity for the time, and the size that other similar towns could reach).

Although it was not on any of the caravan routes, its inhabitants prospered thanks to the good soil that surrounds it, ideal for producing cereals.

The ancient city that survives today on the western side was the administrative, civic, and commercial center of Jerash, and most of its inhabitants resided on the eastern side of the Wadi Jerash.

¶ History

Although remains have been found indicating that the site was inhabited in Neolithic times, it was only during the reign of Alexander the Great (332 BC) that the city truly began to come into its own.

In 63 BC, the Roman Emperor Pompey conquered the region, and Gerasa became part of the Roman province of Syria and, soon after, one of the cities of the Decapolis. In the following two centuries, trade with the Nabataeans was reestablished, and the city grew greatly wealthy. Local agriculture and iron mining in the Ajlun area contributed to its economic well-being. A completely new plan was drawn up in the first century AD, and its main feature was a colonnaded central street crossed by two side streets.

We must therefore assume that in Jesus’ time, this city was in the midst of a process of urban change. Construction activities were therefore very significant.

Some ruins that exist today postdate Jesus’ time, such as the Triumphal Arch to the south of the city, which was erected by Hadrian when he resided there for a while. However, the rest is almost as it was during Jesus’ lifetime, although some of the current ruins rest on buildings that were previously erected and then enlarged during later periods of the Empire.

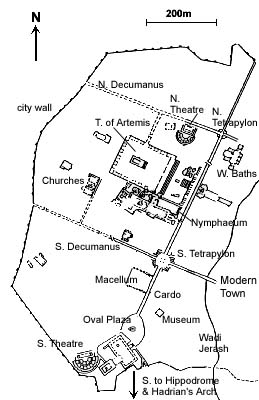

¶ Description

Coming from Philadelphia, the first thing that would come to the traveler’s eyes would be the hippodrome, the ancient sports arena that used to be surrounded by seating for up to 15,000 spectators. It had its entrance at its northern end, and some of the stands have been restored today. The arena, 244 x 50 m, was primarily for athletic competitions and, as its name suggests, horse racing.

Near the hippodrome is the south gate. The gate, originally one of four in the 3,500 m long wall, was decorated with acanthus leaves.

Once inside the gate, the Temple of Zeus was the closest building to the left. It had a flight of steps supported by vaults that led into the interior from a lower sacred precinct. The temple itself was still under construction in Jesus’ time. In the lower part, or temenos, was an altar and served as a sacred place for sacrifices. This place had been sacred since ancient times, containing several temples over time.

The Forum is unusual because of its oval shape, which some attribute to a desire to elegantly link the main north-south axis (cardo, the classical Roman main street) with the existing Hellenistic sacred site of the Temple of Zeus. Indeed, some historians argue that it was a forum (marketplace) in the strictest sense of the word, suggesting that it may also have been a sacrificial site connected with the temple. Reconstructed Ionic columns indicate that it was an impressive sight. The center was paved with limestone and other soft stone blocks. A statue stood on the central podium.

The South Theater, behind the Temple of Zeus, was built during the time of Jesus and could seat 5,000 spectators. The rear of the stage was originally two stories high. From the top of the stands, there was an enviable view of the city.

At the far end of the forum, the cardo, or colonnaded street, stretches for over 600 meters toward the north gate. The street still retains its original pavement today, and the ruts left by thousands of chariots over the years can be seen.

At the two main intersections, ornamental tetrapylons were built. The South Tetrapylon consisted of four bases, each with a column supporting a statue.

The cross street (decumanus) runs eastward, descending to a bridge over the small river and continuing to the Eastern Baths, and westward to a gate in the city wall. To the left, before this cross street, was the city agora. It had a fountain in its central part.

About a hundred meters beyond the intersection was a temple (forgotten in Jesus’ time) dedicated to the Nabataean god Dhushara.

Following the cardo was the Nympheum, the city’s principal ornamental fountain and a temple dedicated to the nymphs. The one that stood in Jesus’ time was replaced the following century by a more lavish one. The building, usually two stories high, drained into a pool and then into the street below.

Continuing to the left was the most impressive building on the site, the Temple of Artemis, dedicated to the city’s patron goddess. After the Great Temple Gate came two flights of steps leading down to the courtyard where the temple once stood. Large vaults had to be built to the north and south of the temple to level the courtyard. Originally, the temple was surrounded by columns, but today only the double rows of the front remain, as the columns and other materials from which the temple was built were reused for later buildings such as churches.

Continuing along the main street again was the second major intersection and the Northern Tetrapylon. It differed from the Southern Tetrapylon in that it consisted of four arches supporting a vault.

The Western Baths were descending from the Northern Tetrapylon. There were some in Jesus’ time, and later the ones that remain today were built on top of them.

The Northern Theater, just west of the Tetrapylon, was smaller than the Southern Theater. From the northern tetrapylon it is only about 200 m to the North Gate.

Immediately to the west and south of the Temple of Artemis were other temples dedicated to a number of other Greek and Roman gods (remember that the population was made up of both).

¶ The Urantia Book

We are told that Jesus passed through this city on his way to Jerusalem when he took his younger brother Simon to celebrate the Passover there (UB 128:3.2). He also passed through with John Zebedee when Jesus went to Jerusalem for a few days before beginning his public work (UB 134:9.1).

It was one of the towns visited during the first preaching tour on the Sea of Galilee, from June 23 to July 7 A.D. 26, which was undertaken by the twelve alone. (UB 138:9.3)

It was one of the towns visited during the first preaching tour of the Decapolis, from November to December 27, undertaken by Jesus, his twelve apostles, and the twelve apostles of John the Baptist (UB 144:7.1). After his return from Phoenicia in August 29, Jesus traveled to Jerusalem and passed through Gerasa (UB 152:7.1).

It is one of the towns visited during the second Decapolis preaching tour from August to September 29, which was undertaken by the Twelve and a band of evangelists without the continuing presence of Jesus (UB 159:0.2). It is one of the towns visited in the Perean mission, Jesus’ final missionary effort in 30 AD (UB 165:0.1). There Jesus delivered a memorable discourse on “how many will be saved” (UB 166:3).

¶ References

- Wikipedia

- Urantiapedia

- Art and Archaeology

- Mapping Gerasa: a new and open data map of the site. Cambridge University Press

¶ Hiccups (Susita)

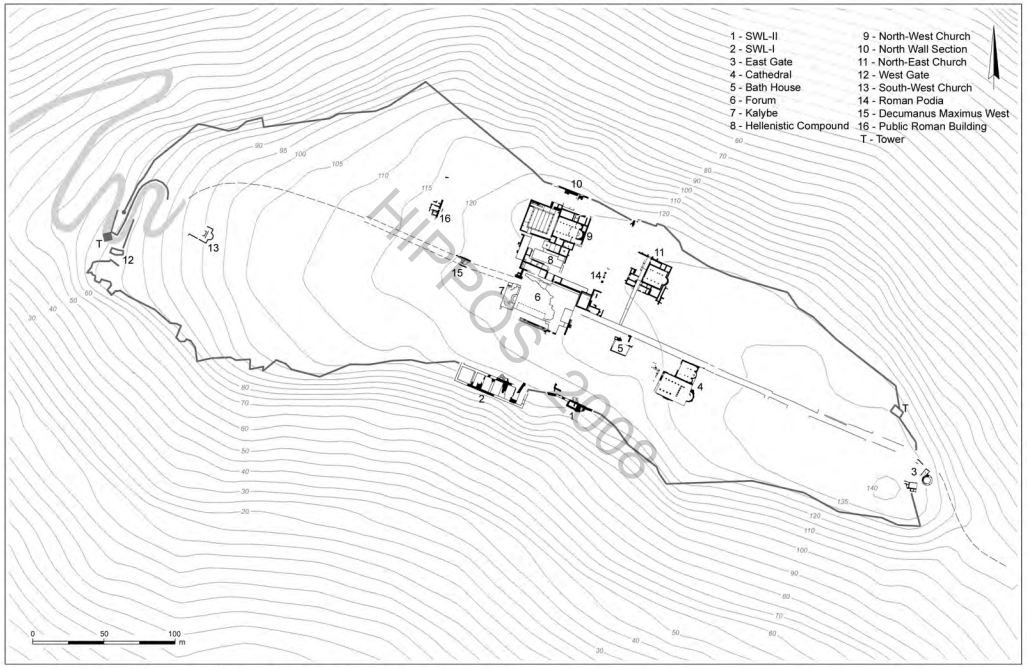

Hippos or Hipos (from the Greek “horse”) or also Susita (in Aramaic and Hebrew) is an ancient city, now an archaeological ruin, located on a hill 2 km east of the Sea of Galilee. After forming part of the Decapolis, it became a Christian city until it was abandoned due to an earthquake in 749.

It was built on a flat-topped hill 350 meters above the Sea of Galilee.

In addition to the fortified city atop the mound, Hippos had two ports on the Sea of Galilee and a large surrounding area under its control (see map of the Decapolis territories).

¶ History

The city was founded in the mid-2nd century BC as Antioch of Hippos. Hippos means horse in Greek and was a common name among Seleucid monarchs. In some references to the city, it is identified by its Aramaic name, Susita, which also means horse.

Archaeological evidence shows that Hippos was inhabited from the Early or Middle Chalcolithic period. The site was rehabilitated in the 3rd century BC by the Ptolemies, although it is unknown whether it was solely as a military settlement or as a city. During this time, the region, known as Coele-Syria, served as a battlefield for Alexander the Great’s generals after his death. Later, after being built as a city by the Seleucids, it acquired the name Antioch Hippos. A temple, a central market, and other buildings were built. The scarcity of water at such an elevated location necessitated the construction of cisterns.

In the 1st century BC, the Hasmonean Alexander Jannaeus took control of the city, and according to Josephus, the inhabitants were forced to convert to Judaism.

In 63 BC, Pompey conquered Coele-Syria, along with Judea, and put an end to Hasmonean independence. Hippos was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria. Under Roman rule, Hippos gained a degree of independence and minted its own coins, inscribed with the image of a horse.

Given to Herod the Great in 27 BC, it was returned to Syria upon his death in 4 BC. According to Josephus, during this time, Hippos, a pagan city, was the “sworn enemy” of the new Jewish city across the lake, Tiberias. Josephus relates that during the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-70 AD, the Jews of Hippos were massacred.

After the Bar Kokhba revolt, which was suppressed by the Romans, the city became part of the province of Syria Palestine in 135. At the beginning of the 2nd century AD, Hippos reached its peak of prosperity and growth.

¶ Description

The city was built along a grid pattern, centered around a colonnaded decumanus maximus that ran east to west through the city. It was crisscrossed by several north-south cardinas, or streets. At the center of the city was a wide, rectangular forum paved with basalt slabs. Beneath the forum was a water reservoir roofed with an impressive barrel vault. Other nearby monuments included a kalybe (a shrine to the Emperor) from the 2nd or 3rd century AD, a Hellenistic sanctuary or temenos, a late 1st-century basilica, an odeon, baths south of the forum, and the obligatory walls. The highlight, however, was a 24-km-long aqueduct, bringing water to Hippos from the El-Al Stream in the Golan Heights.

The city had two gates, one located at the eastern end and the other at the western end of the decumanus maximus. The gates had a 3.15 m wide passage surrounded by two round towers. The fortifications must have dated to the Roman period. Along the wall, at irregular intervals, a small number of square or rectangular towers were erected.

The most unusual example of Roman military architecture excavated at Hippos is the bastion (a battery for ancient missiles, catapults, and ballistas). The bastion, a 51 x 10 m basalt construction, was erected on the edge of the southern cliff, about 40 m south of the forum. Its solid, fully exposed basalt wall structure is intersected by four chamber vaults and two towers. The chamber vaults were covered with floors, few of which remain. The bastion was built in the 1st century AD and partially dismantled during the 2nd century AD, reusing it for the southern baths.

Regarding the port on the Sea of Galilee, this was the second most important port on the eastern shore of Lake Tiberias. The truth is that the dimensions and configuration of this dock did not correspond in size to the village located along the shore. This village merely served as a river port for Hippos. A Roman road ascended to the top of the city and entered through the western gate.

The port had unique characteristics. The main breakwater was 120 m long, with a width at its base of 5 to 7 m. It ran perpendicular to the coast, and after 15 m it changed direction, running parallel to the shore, heading south. This second section reached a length of 85 m. Suddenly, the embankment changed direction, heading west. This curious inverted Z, undoubtedly battered by the southerly winds, was closed by a second 40 m breakwater, which ran perpendicular to the coast. The most curious thing was that this 20 m long pier jutted westward, into relatively deep waters (between 4 and 5 m). The reason for such a disproportionate port location was that it could be used for docking and unloading operations without having to enter the port. The explanation for this remarkable landing stage is that with Pompey’s acquisition of the upper city, Hippos, and its harbor, they became a flourishing emporium, growing and becoming the second urban entity on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

¶ The Urantia Book

Hippos was one of the sites visited during the preparation period for the twelve, the first solo preaching tour on the Sea of Galilee, from June 23 to July 7, 26 A.D. (UB 138:9.3).

It was also one of the sites visited by Jesus, the twelve apostles, and the 117 evangelists during the second Galilean preaching tour, from October 3, 28 A.D. to December 30, 28 A.D. (UB 149:0.1).

It was one of the towns visited by the Twelve, the twelve evangelists, and other women evangelists during the second tour of the Decapolis from August 18 to September 16, 29. Here Jesus delivered a sermon on forgiveness in response to a disciple’s question (UB 159:0.2, UB 159:1.1).

¶ References

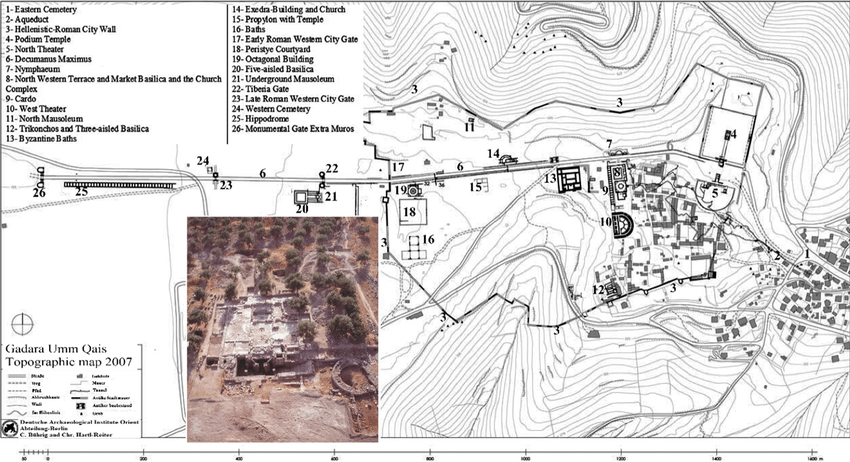

¶ Gadara

Located to the north of the Decapolis, in the vicinity of the Yarmouk River, overlooking the Golan Heights and the Sea of Galilee to the north, and the Jordan Valley to the south. It is currently the city of Umm Qais.

¶ History

The city was captured from the Ptolemies by the Seleucids in 198 BC, and the Jews under Hyrcanus took it from them in 100 BC. When the Romans (led by Pompey) conquered the East and the Decapolis was formed, the fortunes of Gadara, taken from the Jews in 63 BC, increased rapidly, and typical large-scale construction began.

The Nabataeans controlled the trade routes north to Damascus itself. This interference with Roman interests led Mark Antony to send Herod the Great to conquer them. The Nabataean king was finally defeated in 31 BC. Herod was given Gadara after a naval victory and ruled it until his death in 4 BC, much to the chagrin of the locals, who had tried everything to make him lose Roman favor. After his death, the city reverted to a semi-autonomous state as part of the Roman province of Syria.

Gadara continued to prosper throughout the following century, into the 1st century AD and beyond. Its importance is evidenced by the fact that it eventually became a bishopric, which only disappeared with the Muslim conquest.

¶ Description

The few ruins that have survived show a typical fortified Roman city, with a Roman road, a colonnaded street (which was probably the city’s commercial center), and a theater in the western area. The theater must have been colossal, with magnificent views over the Sea of Galilee.

The theater and some of the columns are made of black basalt (as are many of the modern houses in the area, undoubtedly built with materials stolen from the ruins). Further west along what remains of the Roman road, there is a mausoleum, then some baths on the right, and further down, another mausoleum on the left. A few hundred meters further would take us to the outskirts of what was once a hippodrome. In 2017, archaeologists discovered an ancient temple built in the Hellenistic period, in the 3rd century BC. It is believed to have been dedicated to Poseidon.

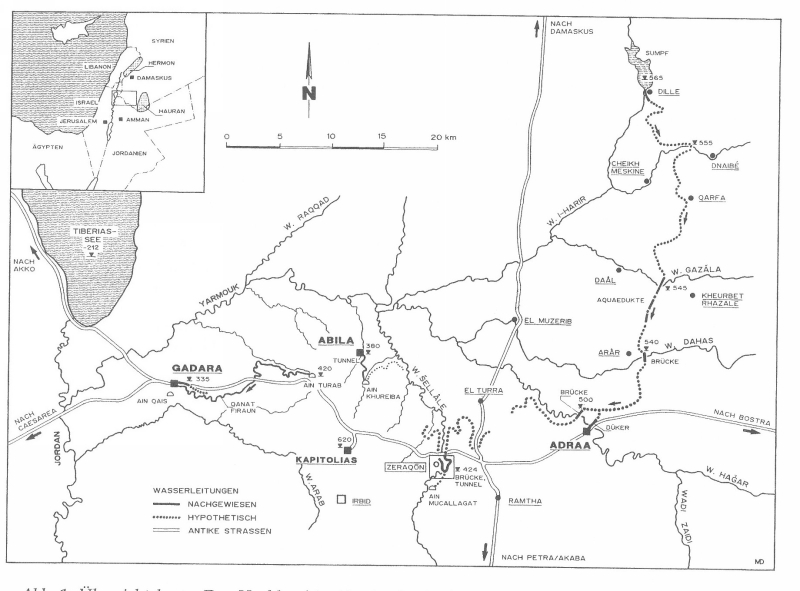

A 2nd-century AD Roman aqueduct supplied drinking water to Gadara via a 170-km-long qanat (an underground aqueduct). Its longest underground section, at 94 km long, is the longest known tunnel from antiquity.

¶ Illustrious figures

Gadara was famous as early as the 3rd century BC for its cultural importance. Several philosophers, poets, and mathematicians were born there. Gadara was once called the “city of philosophers.” Menippus was a slave turned philosopher from the 3rd century BC, whose works were imitated by Varro and Lucian; Meleager, from the 1st century BC, was one of the most admired Hellenistic poets; Philodemus, also from the 1st century BC, studied philosophy in Athens and was one of the greatest exponents of Epicureanism; Philo, of the 2nd century AD, was a mathematician who was able to calculate the value of π with great precision.

¶ Hammat Gader

The baths at Hammat Gader were about 10 km (6 mi) from Gadara, down the hill toward the Yarmouk River and the Golan Heights. The area near the river and the springs is very green, making a strong contrast to the steep, arid Golan Heights.

The baths were famous in Roman times for their health-giving properties and are still in use today.

¶ The Urantia Book

Thomas Didymus was a fisherman from Tarichea but was once a carpenter and mason in Gadara (UB 138:2.5). Gadara was one of the towns visited during the first work of the twelve, from mid-August 26 to the end of 26 (UB 138:9.3).

It was one of the sites visited by Jesus, the Jesus Twelve, and the John Twelve during the first preaching tour in the Decapolis, between November and December 27 (UB 144:7.1).

It was also one of the sites visited by Jesus, the Jesus Twelve, and the 117 evangelists during the second preaching tour in Galilee, between October 3, 28, and December 30, 28 (UB 149:0.1).

It was one of the towns visited by the Jesus Twelve, the twelve evangelists, and other women evangelists during their second Decapolis tour, from August 18 to September 16, A.D. 29. (UB 159:0.2). It was one of the sites visited on the Perean mission, from January 3, A.D. 30, until Jesus’ death. (UB 165:0.1).

The Gospels mention an event, the exorcism of the Gadarene demoniac (Mt 8:28-34; Mk 5:1-20; Lk 8:26-39), which is suggested to have happened in Gadara, but which The Urantia Book actually identifies with Kheresa (also called Gergesa in Spanish), the home of the Alpheus twins. It makes much more sense that it was this location. Neither Gadara nor the other proposed solution, Geresa, are towns near the shore of the Sea of Galilee. See Amos, the lunatic of Kheresa.

¶ References

- Wikipedia

- Universe in Universes — Gadara (Umm Qais)

- Roman Aqueducts

- The white marbles and polychrome stones of the five-isolated basilica at Gadara (Umm Qais), Jordan: archaeometric characterization for provenance

- The Eastern City Area of Gadara (Umm Qais): Preliminary results on the Urban and Functional Structures Between the Hellenistic and Byzantine Periods

- Heritage Management: Analytical Study of Tourism Impacts on the Archaeological Site of Umm Qais—Jordan

¶ Damascus

Damascus is today the capital of present-day Syria, a holy city of Islam, and a major cultural center of the Levant and the Arab world. At the time of Jesus, the city was part of the Decapolis.

¶ History

Damascus claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, although its northern rival, Aleppo, hotly disputes this title.

Egyptian hieroglyphic tablets refer to Dimashqa as one of the cities conquered by the Egyptians in the 15th century BC, but excavations in the courtyard of the Umayyad Mosque have revealed finds dating back to the third millennium BC.

Damascus has been the object of struggle on numerous occasions and some of its first conquerors were King David of Israel, the Assyrians in 732 BC, Nebuchadnezzar (around 600 BC) and then the Persians in 530 BC. In 333 BC it fell into the hands of Alexander the Great. Greek influence declined when the Nabataeans occupied the city in 85 BC. Shortly after, in 64 BC, the Romans forced the Nabataeans to leave and Syria became a Roman province. It was here that Saul of Tarsus became Paul the Apostle.

¶ Description

Let’s try to get an idea of what the city was like in the time of Jesus.

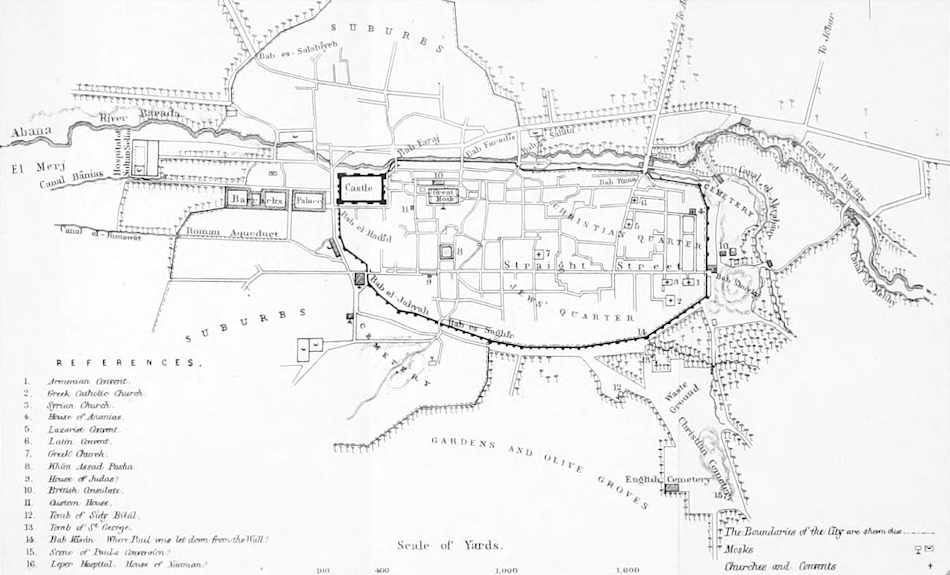

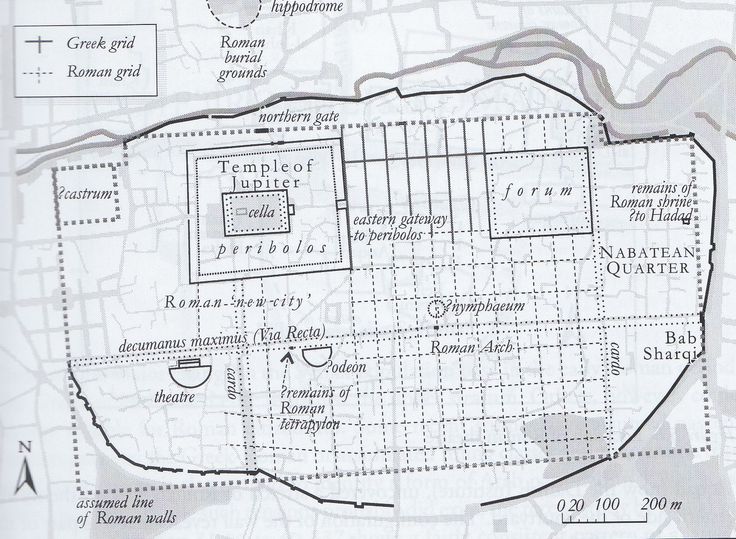

Old City

Most of the attractions of today’s Damascus are in the Old City, surrounded by what was once the ancient Roman wall. The wall has been torn down and rebuilt numerous times over the past 2,000 years. The one standing today dates from the 13th century, but follows the guidelines of the one that existed in the 1st century.

Various gates opened up the wall, but only one of those that exist today (the East Gate) dates back to Roman times.

Citadel

This was located in the western wall. It is currently being restored.

Temple of Jupiter

Located near the Citadel, next to the great Umayyad mosque, in the western sector. It was built on what was formerly a temple to the Aramaic god Hadad (the storm god) in the 9th century BC. It is assumed that a temple to a Roman god existed here at the time of Jesus, although the current temple ruins correspond to a 3rd century AD temple. It is assumed that it was built to enhance the existing one. Today the temple is the Umayyad Mosque.

Straight Street

This was the ancient decumanus maximus, the main Roman road, running east to west. It is famous for a passage in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 9:11), where a man (Judas) is mentioned whom Ananias, a disciple, was to ask about Paul. Curiously, this house and street were also supposed to exist during Jesus’ lifetime.

¶ The Urantia Book

Jesus met a mathematics professor from Damascus, and after learning some new arithmetic techniques, he devoted much time to mathematics for several years (UB 123:6.3).

In 17 AD, after a visit to Jerusalem in which Jesus took his brother Simon for the Passover, they met a merchant from Damascus. This man offered Jesus a job in Damascus, but Jesus politely declined (UB 128:3.3). Later, at the merchant’s insistence, Jesus agreed to spend a few months of that year in Damascus organizing a new school (UB 128:4). This event in Jesus’ life led to his being known for a time as the “scribe of Damascus” (UB 129:3.2).

Jesus passed through Damascus on his return journey from Rome with Ganid and Gonod (UB 130:0.3, UB 133:8), in the year AD 23. On his return from Charax, where Jesus said goodbye to Ganid and Gonod, he returned to Damascus (UB 134:1.1).

After his journey to the Caspian Sea, Jesus returned in a caravan that passed through Damascus (UB 134:2.5).

The apostle Paul experienced a sudden and dramatic conversion one memorable day while on the road to Damascus (UB 100:5.3). Although The Urantia Book does not specify why, it is striking that it says nothing about an appearance or voice from Jesus (Acts 9:1-9).

¶ References

¶ Abila

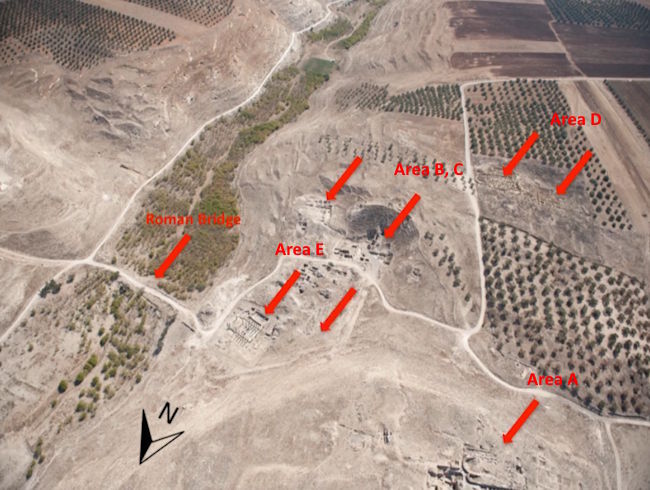

Abila, known as “Abila in the Decapolis,” and also known for a time as Seleucia and Abila Viniferos, was a city in the Decapolis; the site, now known as Qweilbeh, occupies two tells, Tell al-Abila and Khirbet Tell Umm al-Amad.

The name Abila comes from the Semitic word Abel (“meadow,” Arabic for “greenery”). The site lies among green agricultural fields near the present-day Ain Quweilbeh spring, with olive groves and wheat fields.

¶ History

The site was in use from the Neolithic through the Abbasid/Fatimid and Ayyubid/Mamluk periods, from 4000 BC to 1500 AD. Excavations have been more intensive since 1980, although much remains unexcavated.

Polybius and Josephus mention the capture of the city by the Seleucid king Antiochus III in 218 BC. The Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus then conquered Abila during his wars of expansion. Eventually, Abila was taken by the Roman general Pompey in 63 BC and granted independence. In the later Roman and Byzantine periods, Abila achieved a position of regional importance as part of the Decapolis, as evidenced by an inscription from the time of Emperor Hadrian (117–138).

Archaeological evidence from this period includes a temple and coins showing the veneration in the city of Heracles, Tyche (goddess of fortune), and Athena (goddess of wisdom).

Abila continued to prosper during the Byzantine period and became an important regional Christian center (with a bishop’s see), as evidenced by the presence of several large churches. It suffered a period of abandonment in the 7th century until it was reoccupied during the Umayyad period.

¶ Description

Archaeology confirms that the settlement on the northern hill (Tell al-Abila) was the original Abila. Most of the city lay on the saddle-shaped surface between the two hills, with the slopes bridged by terraces.

The wall, initially built in the Iron Age and strengthened under Macedonian and Roman rule, defined an elongated rectangle beginning on the slope of the northern tell and continuing to the crest of the southern hill. The existence of a cardo maximus running north to south parallel to the western wall has been proposed, as has a decumanus winding east to west along the channel between the hills.

A 6th-century church has been unearthed on the northern hill (Area A). Another 7th-8th century church has been unearthed on the southern hill (Area D). A theater was built on the slope of the southern hill, on top of which an Umayyad fortress was later built. To the north of the theater, a nymphaeum and baths have been found. Also near the theater, a Roman plaza measuring about 12 meters on each side has been discovered.

To the west of the depression between the two hills, a five-aisled Byzantine basilica has been unearthed. The basilica was located near the eastern Roman gate that crossed the channel of the Wadi Qweilbeh, which bordered the city to the east.

¶ The Urantia Book

This was one of the places where the twelve apostles preached during the first work of the twelve between mid-August A.D. 26 and the end of that year (UB 138:9.3).

Jesus, the twelve apostles, and the twelve from John preached in this city during the first Decapolis preaching tour between November and December A.D. 27 (UB 144:7.1). Nathanael preached here during the second Decapolis tour between August 18 and September 16 A.D. 29 (UB 159:4.1). There he had a profitable conversation with the Master concerning the truth contained in the Jewish Scriptures.

¶ References

- Wikipedia

- Site information, John Brown University

- The 1996 Season or Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis

¶ Dium

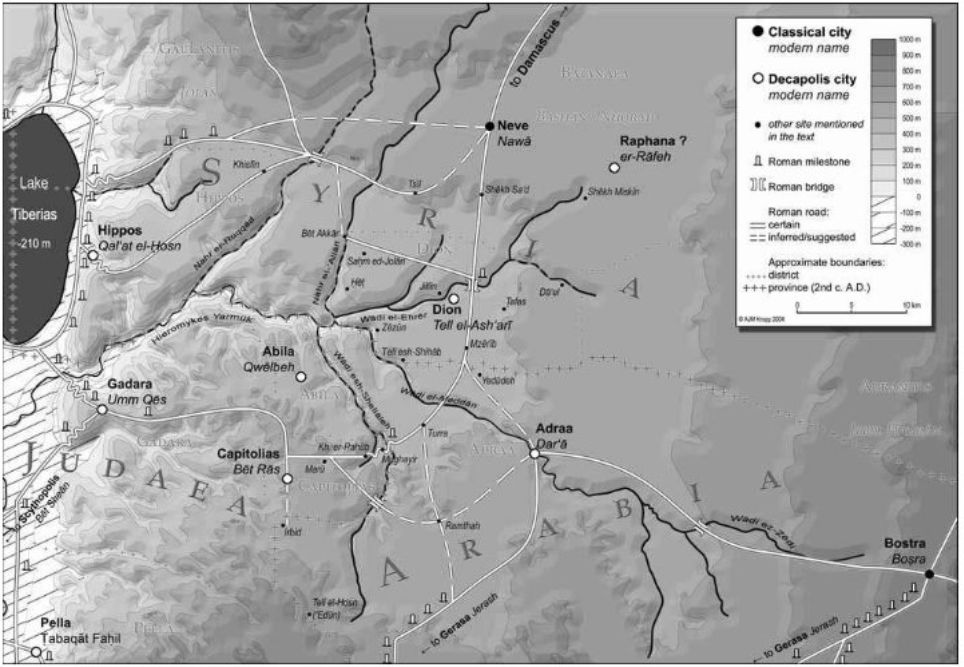

Dium or Dion, or Dia, was a city of ancient Coele-Syria mentioned by numerous ancient writers. According to Stephen of Byzantium the city was founded by Alexander the Great and was named after the city of Dium in Macedonia. It is primarily identified with Tell el-Ash’ari in the Daraa Governorate in southwestern Syria, although another possible identification is Beit Ras, which is another location considered for Rafana and Capitolias.

Therefore, the location of Dium is not definitively proven. According to Ptolemy, the city was located between Pella and Gadara. Josephus, in his account of Pompey’s journey through the area, states that he arrived from Damascus via Dium to Pella, placing Dium north of Pella. The ruins of Tell Ash’ari reflect the concept of a small Greek hill town and its surroundings. A theater located high above the Yarmuk River ravine is unfortunately in very poor condition due to the civil war.

As a curiosity, it is worth noting that Dium, unlike all the other cities of the Decapolis, was not a bishop’s seat.

¶ History

Stephen speaks of it and comments that its water was unsafe. Little is known of its history. Like most of the Hellenistic cities in the region, it was subjected to the Jews under Alexander Jannaeus, who conquered it, and was later conquered by Pompey, regaining its freedom in 62 BC. Coins minted at Dium date from the Pompeian period. Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy include it among the cities of the Decapolis.

¶ Description

Little can be said of what this town was like in the time of Jesus. The most likely site, Tell Al-Ash’ari,Near a town called Tafas, it is a hill located next to the ravines formed by the Yarmuk (Hieromykes) River as it passes through the area. It is a well-irrigated area with extensive cultivated fields.

The most notable feature of the hill is a very thick defensive wall, which surrounds the southeastern area, leaving the northwestern area open, which overlooks the ravine, creating a natural fortification. There are also traces of towers on the sides. A ramp leads to the south side and ends at a city gate. All these remains date from the Bronze Age.

From the Roman period, remains of a small theater, 20 meters in diameter, have been identified on the eastern slope and facing southwest. Ruins of a 100-meter-long pool for collecting water from the nearby spring have also been discovered, which some archaeologists have identified as a naumachia. Another discovery is a necropolis located to the northeast.

Starting from the eastern edge of the mound, the existence of an ancient path has been observed that led to the main bridge over the Wadi al-Ehrer, the tributary that later flows into the Yarmuk.

¶ Roman Roads

Three main roads in southern Syria connected Damascus with Arabia and the cities of the Decapolis. Two of these led to Bostra, the main urban center in the northern half of the province of Arabia, home to Legio III Cyrenaica and perhaps the seat of the governor; one followed the eastern edge of the basaltic desert of Trachonitis (Leja), and the other, still in a good state of preservation, cut through it.

Dium’s access to the road network was via the westernmost of these three Roman roads, which followed a connection of great antiquity from Damascus to northern Transjordan. It avoided the dangerous border area to the east and instead crossed the plain of Batanaea (Bashan). Written evidence for this road comes from the Itineraria Antoninianum, the main catalog of roadside stations with relative distances to each other from the third century AD. C. Two itineraries list the following stations: Damascus 23 mp – Aere (as-Sanamen) 32 mp – Neve (Nawa) 30 mp – Capitolias (Bet Ras) 36 mp – Gadara (Umm Qes) 16 mp etc.

Only a small part of this route is visible, from Damascus to just before As-Sanamen. Its subsequent route, especially the long stretch between Neve and Capitolias, is a matter of debate. There is a significant paucity of evidence. What is certain is that the road from Damascus to Capitolias crossed the Wadi al-Ehrer at the Jisr (bridge) al-Ehrer, 2.5 km north of Tell al-Ash’ari. As mentioned above, a Roman bridge is known to have existed. In addition, the base of a Roman milestone has been found on the north side of the Jisr al-Ehrer. Right at Jisr al-Ehrer, this southbound road was joined by a transverse axis that descended from the Golan Heights past Bet Akkar and Sahm al-Jolan. South of Wadi al-Ehrer, the road passed between Tafas and Tell al-Ash’ari, crossed the shallow Wadi ed-Dahab and the Wadi al-Meddan. To reach the plain of 'Ajlun in modern Jordan and continue towards Capitolias (Bet Ras), the road had to turn west around Turra, cross the steep and wide Wadi esh-Shellaleh, and immediately afterward the Wadi er-Rahub, until it continued across the plain towards Capitolias. In summary, the distance of 50.4 km between Neve and Capitolias indicated in the Itinerary may seem excessive, since it is only 35 km as the crow flies. But these inevitable detours through the wadis in fact confirm the indicated mileage.

There must have been another road connecting Adraa (Edrei) directly with Dion and Neve. Adraa was the central point for the routes from Capitolias and Bostra, as well as from Gerasa. There is no epigraphic evidence of a connection between Neve and Adraa, but its existence is confirmed by a halakhic discussion in the Palestinian Talmud. Coming from the Golan, the priests not only reached Neve, but from there they went to Adraa and finally to Bostra. We can maintain the indisputable point that the Roman bridge over the Wadi al-Ehrer is the point where the great road from Damascus ran south and passed near the Tell al-Ash’ari (Dium) to enter the Decapolis. Like its neighboring Greek cities, Dium must have benefited from this privileged access to this trade route, which was particularly profitable for the supply of incense from South Arabia. At the same time, Dion was strategically located in a hotly contested border area between the Nabataean, Jewish, and Roman spheres of interest, along the route frequented by both soldiers and pilgrims from Babylon on their way to Jerusalem.

¶ The Urantia Book

Dium (Dion) is mentioned as one of the towns visited by Jesus, the Twelve, and the Seventy during the Perean mission from January 3, 30 AD until Jesus’ death (UB 165:0.1).

¶ References

- Wikipedia

- Dion of the Decapolis. Tell al-Ash’ari in southern Syria in the light of ancient documents and recent discoveries

¶ Rafanah

Rafanah was one of the cities of the Decapolis mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia (Book V.74).

The location of this city is still not very clear. It has been identified with Raphon of the Maccabees or with Abila in the Wadi Keilbeh, but there is no archaeological evidence that Abila was ever called anything other than Abila dekapoleos, Abila Seleukia, or Abila viniferos, and Eusebius mentions it in his Onomastikon as being 12 miles east of Gadara.

Recent research has found a plausible location in the northwest of the Decapolis, which agrees with an account by Josephus of fortresses at a place called Raepta, perhaps a predecessor settlement of Raphanah. Further evidence is a note in the Notitia Dignitatum (an early late Roman administrative manuscript) that speaks of a town called Arefa which had a Roman military unit, an ala, at that site. It seems that the Decapolis Rafanah, its predecessor Raepta, and its successor Arpha/Arefa are most likely located in the ruins of Khirbet ar-Rafi’ah, located in Ard al-Fanah, southeast of Damascus.

For a time, the city seems to have been the base camp of the 12th Roman legion, Legio XII Fulminata, as well as Legio III Gallica.

¶ The Urantia Book

Although Jesus and the Twelve preached in the Decapolis, this town is never mentioned in The Urantia Book. Whether its location so far east (it is the easternmost Decapolis town) had anything to do with this is unclear, and it means that Jesus and his disciples did not stray that far from the Sea of Galilee. We are also never told that Jesus ever entered Damascus during his preaching in the Decapolis, so it makes sense that such a distant territory was excluded by Jesus and the apostles for carrying out their ministry. This assumption is confirmed by the fact that Canata, another Decapolis town about as far east as Raphanah, is also not mentioned as part of Jesus’ preaching, but rather as part of Aden, a spontaneous preacher who started a movement in favor of the Master after hearing the famous lunatic who had been cured by him (UB 159:2.4).

¶ References

- Wikipedia

- Raphana of the Decapolis and its succesor Arpha — The search for an eminent Greco-Roman City, Perr Community Journal, Archaeology.

¶ Kanata

Kanata is a city located far to the east. It is located on the western slope of the Hauran, and its ruins are today called Kanawât or Qanawat. It is located at an altitude of 1,200 m, near a river and surrounded by forests.

¶ History

It is one of the oldest cities in the Bashan and Hauran areas. It is probably the one mentioned in the Bible as Kenath (Numbers 32:42, 1 Chron 2:23). In Roman times, it is first mentioned during the reign of Herod the Great, when the Nabataean forces defeated the Jewish army. From Pompey onwards, it became part of the Decapolis. In the 1st century AD it was annexed to the Roman province of Syria, and in the 2nd century, under Septimius Severus, it became a Roman colony renamed Septimia Canatha, now part of the Roman province of Arabia.

There was a notable Christian community. We know the name of a bishop, Theodosius, who participated in several councils held in the 5th century.

¶ Description

The extensive ancient ruins of the city are 1,500 m long and 750 m wide. They include a Roman bridge and a rock-cut theater with nine tiers and a nineteen-meter-diameter orchestra pit, as well as a nymphaeum, an aqueduct, and a large prostyle temple with a portico and colonnades. To the northwest of the city is a peripteral temple from the late 2nd or early 3rd century, built on a raised platform surrounded by a colonnade. For years, this temple was believed to honor Helios, but an inscription discovered in 2002 shows that it was dedicated to a local god, Rabbos.

The best-preserved monument today is known as Es-Serai, Seraya, or Seraglio (palace). Historians believe it was a combination of temples, the most intact building of which dates from the second half of the 2nd century AD. We must therefore assume that the Greeks and Romans built this temple on top of an earlier one.

¶ The Urantia Book

As stated before for Rafaná, Jesus seems to have never set foot in this locality. It is only mentioned as a place of preaching by Aden, a preacher whom the apostle John confronted in Ashtaroth, but who ignored it and formed a group of followers in Kanata.

¶ References

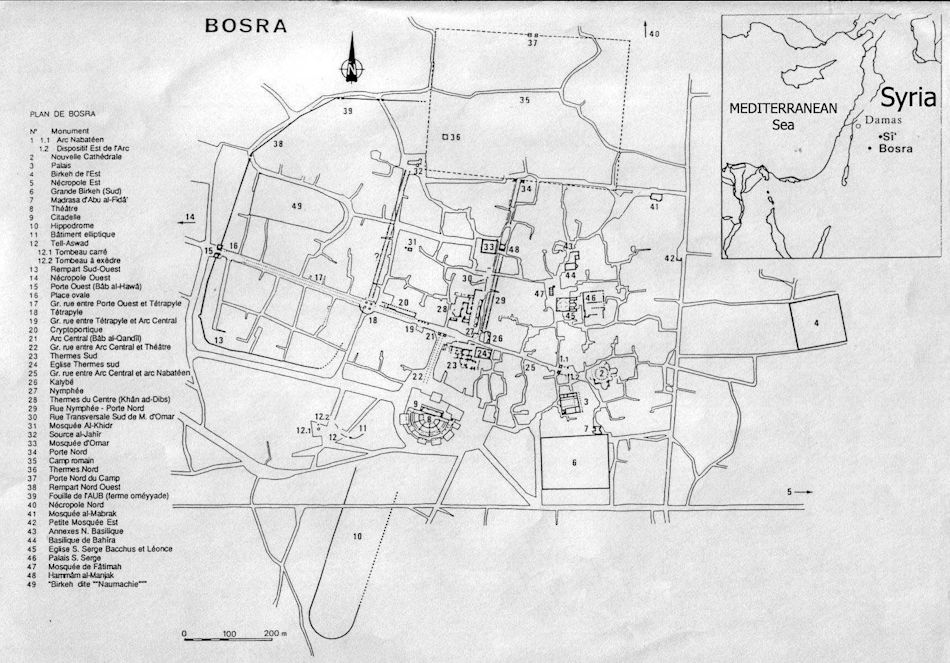

¶ Bosora (Bosra)

The city of Bosra lies between two wadis, both of which reach the Yarmouk River. It lies to the east, across fertile plains teeming with black basalt wadis. It was very important in ancient times because of its location at the crossroads of several trade routes.

It is a strange and wonderful place. Apart from having perhaps the best-preserved Roman theater in existence, the rest of the town is built on, in, and around ancient Roman building remains, almost entirely raised from black basalt blocks.

¶ History

Bosra is mentioned in Egyptian records as early as 130 BC, and during the 1st century AD it became the northern capital of the Nabatean kingdom; the southern capital was Petra.

In 106 AD, the area was annexed by the Romans, and Bosra became the capital of the Province of Arabia, renamed Nova Trajana Bostra.

¶ Description

The citadel is a curious construction, as it largely consists of a fortified Roman theater. Both structures are in fact one and the same (the fortress was built around the Roman theater to make it an impregnable redoubt).

Upon entering the citadel, it is surprising to see this magnificent theater, with a capacity for 15,000 people. Compared to other theaters of its time, it is very unusual because it does not lean against the slope of the mound, as was usual, but rather stands on its own support.

The stage is bordered at the rear by rows of Corinthian columns, and the entire facade was originally covered in white marble. A wooden roof often covered the stage, while the rest of the theater was protected from the elements by silk awnings. As if this were not enough refinement,The atmosphere was sprayed with perfumed water that fell finely on the heads of the spectators.

To the north of the citadel is the main street of the old city, which runs roughly east-west. At the western end is the Great Wind Gate. Along the main street, you can see the remains of the columns found in the excavations.

Another vestige are four massive Corinthian columns, remains of the nymphaeum, which supplied water to people and gardens.

Just behind is another column from what remains of a temple erected by a king of Bozra to protect his daughter from death.

Directly opposite were the Roman baths. They consisted of a series of bathing chambers that bathers would immerse themselves in until they finally reached the steam bath.

Due to the presence of churches on the main street, we must assume that they may have been built on top of what were once pagan temples.

At the eastern end of the street are the Nabataean gate and column. The gate is the main entrance to the palace where the Nabataean king Rabelais II lived. The column is the only one of its kind in Syria and supports the typical, simple Nabataean capital.

Slightly further from the town are two cisterns that used to supply water to the city.

¶ The Urantia Book

Bosora is mentioned in The Urantia Book only as part of the towns that constituted the final missionary effort of Jesus and his followers, from January 3, 30 AD, until the end of his life. In this endeavor, they visited dozens of localities in Perea and the Decapolis (UB 165:0.1).